TAPE 78/AH/01

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 7TH OF SEPTEMBER 1978 AT 14 STONEYBANK ROAD, EARBY. THE INFORMANT IS FRED INMAN, TACKLER AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

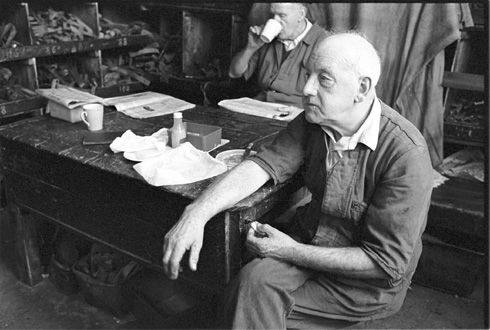

Fred Inman at ease in the tackler's cabin.

Right what I'm going to do Fred is ask you some questions and as I say some of these questions will seem a bit, you know it'll seem to be very simple, but the thing is that when we've done these tapes everything will be very clear.

And also, it's funny how, when you ask the simple questions, you get on to something entirely different if you feel like digressing. If I say something to you and it triggers you off and you think of something, you feel free, because that's what it's about. It's a conversation not an interview. It always takes a while just to break that feeling down but it's just a conversation, because I’m interested, I want to know. 1 want to know about childhood and how things were because I often think there's a lot of people having it far to easy nowadays and they want reminding about the old days. Things like people, well since talking to Ernie, every time I see somebody with bow legs about Ernie's age…

R - Malnutrition eh..

That's it, that's just it, but before I started doing this I never thought about that.

R – No.

Well there you are you see, you’re learning.

R - Aye you learn all time, don't you.

Yes. Anyway how old are you Fred?

R- 69 (Sixty nine).

And where were you born?

R- Earby.

Whereabouts, what street, do you know the address?

R- Well Albion Street, Earby. That ‘ud be it.

Aye. Which is Albion Street?

R - It's at the back of Albion Mill.

That's it.

R- That were Booth & Speak’s.

That's it yes. And how many years did you live in the house you were born in?

R- Oh, happen only about four.

Yes. So your parents moved when you were about four year old?

R - That's it. I can’t remember flitting but they were building some new houses and me father and mother they bought one of these new houses. Well they fastened one [put down a deposit] and that were the first house I can really remember living in properly.

Aye. Whereabouts was that Fred?

R - That was up Lincoln Road just across from Albion Street.

Aye, that's it.

R- And we lived there oh, quite a while.

That ‘ud be just afore the first world war, that ‘ud be 1913 if you were four.

R- Aye it would be something like that, yes.

(50)

Yes, you were born in 1909..

R- Eight.

Oh, you’re seventy this year, you’re sixty nine now.

R- Seventy this time.

When’s your birthday Fred?

R- December the nineteenth.

Oh we'll know then to come and start pulling your hair!

R – Aye, I’ll get it cut then. I’ll get it cut off. [laughs]

Well, they made that move because they wanted to move into a better house, obviously.

R- Oh yes.

That's it. And where was your father born?

R- He had a lot of bother finding out, when he were sixty five. [This would be in connection with him proving his age in order to draw his state pension. My father had a similar problem when he had to prove he was born in Australia when he applied for British citizenship. There were no birth certificates in 1896 in Australia and eventually he satisfied the government by getting an affidavit from the minister at the church where his birth was registered.{ Civil Registration of births, marriages and deaths started on 1 July 1837 in England and Wales. This was later expanded in 1927 to also include still births, and adoptions.}]

His father were one of them like they used to be in them days, a journeyman. Working round reservoirs then coming home, you know. After he’d left, his wife would be having another youngster.

That’s it.

R- And I think me father were born somewhere around Pateley Bridge way.

Aye, so was he a navvy?

R- Me grandfather were, and builder.

Yes.

R- In his later years when he settled down a bit he got on house building then.

(5 min)

Aye.

R- And in fact he built some houses just across there, not these mills, them just across at t’back.

Aye, going down to t’back of Red Lion Street there.

R- Aye, Red Lion Street, Alder Hill View they called it and they had a rough time. Like me father had a rough time when he were a youngster, sommat like Ernest would have.

Aye.

R- Aye me father would be one of about eleven. His mother and the biggest part of family lived in Keighley then. They were allus moving about and of course me grandfather beggared off and started living with another woman.

Aye.

R - Left them. Well when, as children came on and old enough, they'd to get away.

Yes.

R- Well when me father were about fifteen his older sister would be about seventeen she came to Earby. He’d to get out, away you know.

Yes.

R - Then when me father were old enough he came to Barlick.

Aye.

R- And then he came from Barlick to live with his sister in Earby and I don't know, they'd live in a cottage or sommat and then me auntie got wed and me father got wed. and they both stopped in Earby till they died.

Aye. What was your fathers name Fred?

R- Parkinson Inman.

Aye.

R- And that's an old name in the Inman family is that.

My God, it's a fine name isn’t it.

R- Aye you'll find it a lot in the Dales, Parkinson Inman.

Yes aye. Where does, Inman always strikes me as an Earby name, I don’t know why. Where does it originate from? Do you know?

[[The Oxford Dictionary of surnames says that it is Old English, ‘inn-mann’, a publican or lodging house keeper.]

R - Yorkshire. Well there's a few of 'em round, there were, round Bolton Abbey, Burnsall, Appletreewick.

(100)

Aye.

R- There were a few Inmans. And then there were a few Inmans in Skipton. I suppose going back a long while they'd be all from one family.

Like Dales families aye. That's it aye,

R- There were some Inmans you know, further up the Dales.

And so your mother were born at Keighley?

R- No me mother were born at Earby me father were born at Keighley.

That's it aye. Sorry, that's it. I were thinking about your grandmother there. And what was your mothers full name? What was your mothers name?

R - Elizabeth Turner, they were a very old Earby family were them.

Aye, there's still a lot of Turners in Earby isn't there.

R- Yes. And they had a butchers shop on Water Street. I’ve heard me mother tell, they killed in the shop, part of the shop.

Aye.

R - And she'd only be about seven or eight when her father died, so she had a brother older than her and him and his mother they carried on and run butchers shop and me uncle had it until during and finishing up of this war.

Aye.

R- The second world war. He stuck it, he were a well known character.

Aye.

R- They were hard times were them like. I've heard me mother talk about going to Thornton wi’ a basket full of meat and then coming back and going to school.

Yes.

R- When they had to take their slate pencils and that.

Aye, that's it. How many brothers and sisters did you have?

R- I only had one brother.

Oh, there were just two of you. How many confinements did your mother have, did she just have two?

R- Two.

Yes. No, the reason I ask that, I never used to ask people that question and then it turned out Ernie Robert’s mother had eleven confinements and four survived, that were all.

R- Aye.

Now that's rough isn't it.

R- It is aye.

When you think.

R- Yes.

And of course you live and learn you see. So now I ask how many there were in the family and I ask how many confinements there were because there can be a vast difference.

R - Oh yes.

Yes. And were you the eldest of the two?

R – No, I were the youngest. Me brother were a year and nine month older than me.

Is he still alive Fred?

(10 min)

R- No. He were a gardener for the council and I think he must have swallowed some poison of some description. He’d be off and on for nine year bedfast and walking about and bedfast and walking about.

When you say swallowed some poison you mean, poison accident or..

R - Weed killer. Accident aye, weed killer. Aye well that's what I think and he thought the same.

(150)

Aye.

R - You know you could have had some on your finger and…

Yes.

R- ..and put it on your lip or sommat like that. 'Cause it were like a fever what he started with and he started rambling and he had several doctors and nobody had seen owt like it before. And he were lucky in one way, he got all his blood changed. They changed all his blood and they had specialists from down Bradford and further afield to come and look at him at Skipton.

Aye.

R- And he used to blow up like a balloon. He’d be about sixteen stone at some times and then they'd take him down to Skipton and diet him down to about twelve.

Aye.

R- And then they'd send him home again then and once he’d got a lot of this weight up he couldn't walk then so they used to diet him and fetch him down and then he could walk.

It sounds like a rotten do Fred.

R- Oh aye it were a rotten do. His wife had a rough do.

Aye

R- Like, you know, if he weren’t at home he were at hospital at Skipton.

Yes.

R- She had a rough do.

And of course nothing would ever be put down. You know, I mean when I say put down, you know, it would never be actually proved that it was anything like that.

R- No, there were nowt ever proved.

No, there’d have been a big compensation case if there had wouldn't there.

R- Mmm. But he finished up wi’ gangrene, that finished him off.

Aye, well it sounds like a bad do anyway. When you were young can you ever remember any relations living with you, you know, for any period of time?

R - Only had an aunty live wi’ us a bit.

Aye.

R- Aye. A few year. Well I'm saying, happen eighteen months.

Was there a reason for that?

R- Well, she had never been married and I think if I remember reight, it were in them days when they rented houses and your landlord could get you out, make it awkward for you.

Aye.

R- I think that were one reason why she came. She lived with us a bit and then she went to live wi’ another sister at Brierfield. Then she lived with me uncle a bit. Then eventually she finished up at Keighley in some kind of a home. She weren’t mental or owt of that sort.

Aye.

R - She lived there.

Aye like an old folks home.

R- Aye. And she come to a sad end. Went out for a walk one night and a storm came and it blew her into a dam and she drownded.

In Keighley.

(200)

R- Aye, just going up out of Keighley there were a dam. She must have had her umbrella up and gone plodding on or sommat, and not been looking were she were going and gone into where this dam were. Walked into it, there were no railings round and she drowned herself before anybody could get her out.

How long ago were that Fred?

R- Twenty year.

Aye, about fifty eight?

R- Mmm.

It's a sad job. Aye. Did you ever have any lodgers?

R- Before I were born.

Before you were born aye.

R- Aye, they called him Fred, that’s who I were called after.

Is that right?

R – Aye.

Aye.

R- And he were a joiner when they built Earby church. He worked for Charlie Watson.

Aye.

R- And Charlie Watson's did all the joinery work at Earby Church and he worked for them.

When was that church built Fred? Do you know the date?

R - 1906 happen.

Yes. And when you were born what was your fathers job, what was his job?

R - Overlooker. Tackler.

Tackler, he was a tackler.

R- He were a tackler yes.

And where was he working at Fred?

R- Oh, when I were born, happen at Shuttleworth’s. He’d worked at Shuttleworth’s and what they called Hugh Currer’s. Aye it would be Shuttleworth’s.

Where were Shuttleworth’s weaving, which mill were they in?

R- In Big Mill,

Big Mill aye. Tell me something, is Big Mill the same as Victoria?

(15 min)

R - Well they do call it Victoria mill.

Aye.

R- But one's on Albert Street and the other, they just call it Big Mill. Victoria Mill, that were where the big engine were and all that.

Yes.

R- That's Victoria.

Aye.

R- Although they called the other the Dock Yard as we said. Johnsons, Victoria Mill. That were the address of it.

Aye, that's it, like you go into it from the other end now. Like that big shed.

R - Aye.

Aye. I think I've heard some of them call it the Ballroom, haven't I.

R- Oh, that's the middle room in the big mill, the Ballroom. You know, there's a ground floor in the warehouse. And then there's a floor that one half had looms in and the other half was a warehouse and tapes and then above that there were twisting rooms and tape rooms belonging other firms.

Aye, that's it. Aye three storeys there.

R- Three storeys, aye.

Did your father have any other jobs, he'd be a tackler till he died, would he?

(250)

R- No, he were a tackler till 1932 and he bought some land and he built a house on it and started a poultry farm.

Where were that at Fred?

R- Up Stoneybank here, top of Stoneybank.

Aye.

R- And he were on that while me mother started being poorly and they had a good do, enjoyed their selves up there, me mother did an all. And then they came back, he sold it and went to Foulridge. A fellow that lived at Foulridge what bought that, poultry farm, so they swapped, they went into his house at Foulridge did me father until he got this empty, he belonged this, and it came empty did this so he came back into it.

Aye, that's this house is it?

R- This house aye.

Aye.

R- Aye, like he flit from Lincoln Road here in 1927.

Aye. We might as well get it down what's the address of this house.

R- 14 Stoneybank Road.

Aye.

R- But it used to be 14 Spring Terrace.

Aye, Spring Mill.

R- Until they made this on here.

Aye.

R- Aye and when they built a row on here and called It Spring Mount and then they built a row further up and called it Spring Field.

Aye Spring Field school.

R- The school, well they were getting mixed up you know, [mail for]14 Spring Terrace were going to 14 Spring Mount or 14 Spring Field so they changed the address to 14 Stoneybank Road then.

Aye, all Stoneybank, aye. Oh there's happen a bit of sense in it.

And before he was a tackler obviously, well I say obviously, he’d be a weaver would he, your father?

R- Yes. When he left school at first he worked in engineering. He did a bit of engineering like labouring, apprentice and mugging about,

Yes. Now your father, when he left school where would he be living. Would he be living in Earby?

A - No Keighley.

Ah, that's It. That's what I was thinking about engineering. About what age would he be when he moved to Barlick. You said he went to Barlick didn't you?

R- He’d only be about fifteen or sixteen.

Aye, and when he went to Barlick what did he do then do you know?

R- Weaving.

Weaving aye, no idea where?

R- No, I’ve no idea. And when he came to Earby he’d be weaving when he came to Earby. And he were one of lucky ‘uns that got to learn to tackle. It were a thing what were handed down from father to son weren’t it. Relation to relation were tackling. Well he must have been a lucky fellow to get to..

(300)

Either that or ‘cause he was a good man,

R – Aye. to get to learn.

That's as likely a thing as any because it was the good ‘uns that got to be tacklers wasn't it.

R- Mmm. And they used to have to be what they call strong in t’back and weak in th’head hadn't they. They'd to be able to carry these warps and that carry on.

Aye.

R- Well he were never really a big fellow, but he weren’t any dummy like, he could tackle.

Yes because that’s something a lot of people won't realise, that in your father’s day when he were tackling, the tacklers used to carry the warps in didn't they.

R- Yes, oh aye.

(15 min)

They didn't have trolley's, they carried 'em on their shoulder.

R - biggest part of 'em were to carry. Well a good half of them were to carry.

Yes, aye.

R- There were pillars in every other alley, weren’t there.

Yes, aye.

R- But I think in them days they could have lifted a lot more in, you know, two’d 'em.

Yes.

R- But they were that jealous and envious of one another you know, you couldn't do with waiting at the alley end of the other tackler coming [to help you] 'cause he’d make you wait as long as he could because that loom were stopped and every pick counted in them days. [Competition between tacklers to get most wages which relied on the weaver’s production]

Yes.

R- So they used to hoist 'em up on their shoulder and away.

Aye. How old was your dad when he died?

R - Seventy eight.

Oh. well carrying warps didn't do him a lot of harm then did it.

R - No, no. He were allus a fresh air fellow.

Yes, well you are aren’t you.

Aye.

And what year were that Fred?

R - When he died ... nineteen fifty four.

Fifty four.

R - I think that ‘ud be it. Me mother died in fifty two and he died in fifty four.

How old were your mother when she died?

R- About seventy ... seventy four I think.

Aye, well they were both a good age then weren’t they.

R- Aye.

How long had they been married, do you know? It would be a fair while wouldn't it.

R- I couldn't say.

It could be fifty year, couldn’t it.

R- Mm. No they hadn't their Golden wedding. I wouldn’t like to say Stanley.

No. It wouldn't be so far off though, anyway, would it.

R- No, it ‘ud be getting on.

So before your mother married your father he’d be living in Earby. They'd meet in Earby would they?

R- Yes.

Yes. And what would she be doing, she'd be working?

R - Aye. She'd be weaving and helping in the butchers shop and that carry on.

That’s it aye. Yes, the butchers shop. And have you any idea where she wove?

R - No I haven't, I haven't any idea.

It doesn’t matter if you don't know.

R- I only know she could weave.

Yes. Where was your father’s last job?

(350)

R- Working. A.J. Birley’s.

Birley’s.

R- Albion Mill.

Albion, yes.

R- Yes, that was his last job inside.

Aye and then he took to poultry farming.

R - Poultry farming mm...

Aye the out door man, aye. Yes, well I'll turn my little bit of paper over. After she were married did your mother still work In the mill, did she carry on working in the mill.

R – No.

Why was that Fred?

R- As far as I know she finished work and she'd to look after me father. You know what they were in them days.

That's right, yes. No, I understand, I’m a bit that way meself Fred.

R- Aye.

My wife's never worked full time and that's one of the reasons I think.

R- So she never worked full time.

Yes, but that was fairly, it wasn't really common that was it.

R- No it weren’t no.

It wasn’t really common in those days. And so she gave up weaving and looked after the house and obviously when you and your brother come along, the two children. What was your brothers name Fred?

R- Melbourne. Melbourne.

What a good name.

R- After billiard player.

[July 15th 1878. Birth of Melbourne Inman. Four times Professional Champion of English Billiards, 1912 - 1919; and winner of the first ever match to be played in the World Snooker Championships. He beat Tom Newman 8 - 5 in a match which began on 29th November, 1926, and finished on 6th December.]

I think you come out wi’ the sticky end wi’ your name I’ll tell you. Now wait a minute what did you say then? After a billiard player?

R- There were a billiard player weren’t there, a professional billiard player called Melbourne Inman.

I didn't know that.

R- Mm. I think he’d be an Australian. Yes he were up Davis’s street and all that.

[Fred Davis]

Aye.

R- I can remember when I were a kid they used to talk about him.

And was your dad keen on billiards or something then?

R – No, I've no idea.

It just tickled his fancy?

R- It happen just struck him you know.

Aye that's it. It's a fine name anyway isn't it. Parkinson Inman and Melbourne Inman.

R- Aye.

I’ll tell you a funny thing about names like that, there's the foreman at Gisburn auction, a fellow called Clarkson and his name was Pliny Clarkson.

R - Aye.

And I said to him one day I said Pliny, “How did you get that name?” He said “Well you know who Pliny was, don't you?” I said “Aye, he were either a Greek or a Roman philosopher.” “Well” he says “It were me grandad. He were mad, on classics.

(400)

And all of us have silly bloody names like that. I'm called Pliny and one of ‘em’s called Aristotle.” I told him he hadn’t come out too badly, at least it was a short name! It makes you wonder sometimes, it's as bad, they always used to say that one of Cramp Hoyle's daughter's was called Olive but I don't know whether to believe that or not.

R - Does that Clarkson live in Earby now?

You know he could do because he had to give up, he had a bit of a bad heart..

R- That's it aye...

(25 min)

And he does some car dealing.

R- That’s it and he has all the land at the back of Spring Mill. He’s fenced it all off and he has a cow and a couple of calves on and sheep and hens, pigs.

Well that'll be Pliny.

R- Aye he's a reight grand fellow to talk to.

Oh aye he's a nice bloke, big fellow, round face aye.

R- Very nice, good looking fellow.

Anyway, so your mother didn't need anybody to look after the children because she was at home looking after them. And would that, no, you've told me it was in Lincoln Street wasn't it.

R - Lincoln Road. aye.

Lincoln Road, that's it aye. And your brother stayed in the town as well, he didn’t leave the town.

R- No.

No. Did any of the family, you know, that were fairly close to you, that were living in Earby, there would be others of your family, of course there were. Did any of them leave the town in about 1930? You know, when times were bad.

R- No.

You know, leave because they were short of work?

R- No.

No, quite a few left Barlick then and went to places like Earby and what not.

R- No, I'd just one relation and he went in 1920.. 1925 sommat like that. To Whitefield near Manchester and he finished up there. But I mean trade weren’t reight good when he left but it weren’t in the 1930’s or owt of that.

Aye that's it. Now then I’m going to ask you some questions now and they'll take you right back to your childhood. You’ll start remembering things you thought you’d forgotten. Now the house you'll remember best is Lincoln Road.

R- Yes.

And how long did you live in that house Fred? You went when you were four year old so...

R- Let's see I’d happen be about eleven.

(450)

Aye. Good for the brain is this you know Fred!

R - Aye.

I can hear the wheels squeaking here!

R- {Stanley and Fred laugh] Aye well actually he sold that house in Lincoln Road and he bought one what were in Stoneybank at the other side of road and then me brother would be twelve when we went up there. Nearly thirteen 'cause I know he started work, he got two looms while we lived in that other house.

Yes.

R- And then he were allus after a bit of land for some hens and he couldn't get any up here so he went back next door in Lincoln Road to where we’d lived before.

Oh.

R- And it were where we lived first time. It were just two up and two down. Well the next house, it were three bedrooms, there were a little kitchen, living room and a front room and three bedrooms.

Aye.

R- Then that got a bath in then you know, we had a bathroom.

That's it.

R- We had a wash basin upstairs, well we thought we were sommat then.

Oh aye, you'd be living like kings. Aye well, we'll talk about, what we'll talk about is the first house in Lincoln Road, the two up and two down one. So well, there you are, how many bedrooms did it have, two. Aye, so your mother and father would be in one bedroom and you and your brother would be in the other. What other rooms were there Fred?

R - Well a kitchen, you could have lived in it if you'd have wanted, but there were no fireplace in.

Aye.

R- And then a decent living room.

Aye.

R- With an old fire range in and that.

Yes. So there wasn't like a front room as such.

R - No,

No, no that's it, aye. And so this living room, that had the fireplace in.

R- Yes.

What sort of a range were there In there Fred, was it a..

R- The old timer, iron, side boiler and...

Oven?

R - Oven and boiler.

Aye, black lead and silver sand. Aye. Can you remember any of the furniture in the house, does anything stick out in your mind?

R - Aye, we had one of them old time three piece suites. You know sofa and...

Leather?

R - Aye. Horse hair sticking out and prickling the back of your legs.

Is that right? [laughs]

(500)

R - And then there were two chairs, one were a bit bigger. That were father’s chair and t’other were a bit less that were a ladies chair and happen a couple of side chairs.

Aye.

R - And happen a couple of buffets for me and me brother to sit on.

(30 min)

R- Or if there were nobody about in winter time you sat on the carpet up to the fire.

Aye. When you say carpet up to fire, were it a carpet...

R- Th’old peg rug.

Peg rug. Everybody had a peg rug Fred. What were the floor? Were it wood or stone?

R- Wood. Wood in the house, stone in the kitchen.

Yes.

R - It used to be scoured round. There were no oilcloth on..

No.

R- Not in the kitchen, there were oilcloth in the house.

In the kitchen, ever put sand on it?

R- No, me mother used to scour it.

Aye. When you say scour it, scrub it out?

R- With a scouring stone.

Aye. So she’d donkey stone it?

R- Donkey stone.

Aye, aye Lion.

R - It were allus white she didn't use ginger.

I’ll tell you something you won't believe, I just bought a box full of donkey stones.

R- Aye, you've done well.

I went into a shop in Manchester and they were clearing a lot of stuff out. There's a box there on floor. I says How much are the donkey stones? This fellow says “You're joking.” I says “How much are they?” He says two and half pence each. I says I’ll take the box full.

R - Aye.

And do you know what there were as well? A copper posser.

R- Aye.

I says “How much is that?” He says £1.28. I says “I'll take that and all.” Brand new. Anyway that's besides the point. But I got some donkey stones, Lion Brand donkey stone and there were hard and soft and there were white and ginger an all. And there were some of ‘em reight old ‘uns you know, that weren’t cast, that were chopped out of the lump, aye. Anyway that's besides the point, we shouldn't be talking about things like that. Well you didn't have a parlour?

R- No.

So, the furniture was in the living room and which room did you have your meals in?

R- Oh we had 'em in house part.

(550)

Yes, that's it, not in the kitchen like.

R- No.

When you say the kitchen Fred, if the fireplace was in the living room, I assume your mother had a gas cooker.

R - Later on, yes.

Yes. Well what I'm trying to get at Fred is how could it be the kitchen if there wasn’t a fire in. You know if there were no gas cooker. You’d have to have something to cook on.

R- Well we used to call 'em kitchens. I don't know why. There were a sink and probably she used to do all her...

And she'd do her washing in there would she?

R- Aye, washing in the kitchen and I rather think she did all her kneading and that in kitchen.

Aye that's it.

R- And then fetched it in front of the fire when she'd kneaded it.

Aye that's it and so really, before she got her gas cooker, the cooking would be split like between kitchen and front room. Like actual preparation would be done in the kitchen and cooking in the front room.

R - Aye and then fetched in and put in the side oven.

Aye. Did you ever have a rack on pulley's.

R - Yes aye.

Aye.

R- That were in house part an all where fire were.

That's it, over the fire. Ever had any oat-cakes drying on it?

R – Aye, oat-cakes on it.

Aye.

R - Aye, they were popular were them.

Anyway we'll get on to food in a bit. Now that house in Lincoln Road, obviously you didn't have a bathroom. When you wanted a bath, what were it.

R - There were a bath in the kitchen. But when we’d had a bath, me mother used to have to ladle all the water out of it. It were a proper old iron bath you know, but she used to have to ladle the water out.

Aye.

R- It weren’t connected up to go into drain.

Aye, I see.

R - There must have been sommat about it when they built these houses and they put a bath in and I suppose it was, well you'll have to pay rates or sommat, water rates for a bath in. If it weren’t connected up to the sewer they didn't know you were using it. We used to put a hose pipe on to the tap.

(600)

Aye.

R- And put water into the bath with a hose pipe and then she used to have to ladle it out.

And when you say, did you have a back boiler? Was there a hot water system?

R- Aye we had a back boiler.

Oh well that were alright then weren’t it.

R- It were one of them tanks, it weren’t a copper tank, it were just straight up and into this here, like a cast iron square boiler.

Aye, aye upstairs.

R- No, it were in the kitchen.

Aye.

R- It were fairly well up to the roof.

That's it aye.

R- And there were no copper boiler down here.

What were it like, on a bracket, or let into the wall or..

R- No. It were built on some woods what came out and some woods down and then me father boarded it in and made like a cistern cupboard.

Aye.

R- But they didn't keep any clothes in there of course because it used to steam up. When the water got too hot it steamed up and you'd to run it off.

I’ve never heard or seen of one of them before Fred.

R- Aye it were an old timer but it did the job.

Yes, aye. And I always laugh when I ask this question. What night were bath night Fred?

(35 min)

R- Friday.

Do you know everybody's bath night were Friday.

R- Aye.

Everybody, and it was a job filling that bath and it was a job emptying it.

R - Aye.

Who got in first?

R- We both got in together when we were kids.

That's it. And then did that water get chucked out or did your mother use it or did your father use it?

R - No it were chucked out because, in fact I think me father would have a bath when we were playing out sometime..

Aye.

R- It weren’t a popular do like for me father and me mother having 'em at Friday, they'd have ‘em when we were out.

Aye, that's it aye.

R - 'Cause there were no privacy.

No that's it. Aye and people were more, you know, I mean…

R- More Victorian in them days.

Well more reticent, aye yes in some ways yes. And did you have a closet, was it inside our outside.

(650)

R - Outside, tippler.

It were a tippler aye, were it a deep one?

R - No it weren’t reight deep up there.

Aye. Ever any trouble with the tippler box?

R- No, me father used to keep it well oiled and lift the flag up and put some oil on.

I always said, we used to have a tippler at Sough, not so long since, about 1956, and I always used to say that there were nowt wrong with tipplers as long as you kept ‘em clean and you looked after them. I think they were a good idea and it were grand in winter if some reight hot water come down, if somebody were having a bath.

R- Aye.

Aye 'cause it could warm it up couldn't it!

R - It could! [Laughs]

I'll tell you where the best tippler were for that. I've heard Newton Pickles talk about it. There were two tipplers in the yard at Wellhouse mill and the drain that they went into must have been a common drain with some water that were coming out of the engine house and he said in winter it were lovely. He said it was a two seater and he said if you sat on one all steam come up through the other. [Laughs] And he said if two of you sat down, bye god he said you could get warmed up!

R- Aye.

Aye, and he said you could see steam puffing with the engine. You could see it, you know there must have been a drain running into it.

R- Aye, that's it.

You know, out of the engine.

R- Oh they were all right weren’t they, they did a job with all the waste water didn't they.

Yes.

R- Swilled it away.

And as you say, they didn’t waste any water.

R- No.

No, like anything else, as long as they were looked after and kept clean. Would you say that tipplers then were a common thing or would there be some dry closets an all?

(700)

Well in Earby biggest part would be tipplers, there’d happen be an odd dry one here and there that’s all.

We're talking now like during the first world war aren’t we.

R- No Earby, they'd had new sewerage and same as Kelbrook there were a lot of night soil closets up there as they called 'em.

That’s it, night soil men, aye.

R- Thornton and ...

Can you, let's see 1909, you'd be five years old when the Great War started. Well the First war. Can you remember anything about it at all?

R- I can remember it starting, that's one thing that stuck in your memory. When you were going to school you know, they talked about war and may be the Territorials would come marching through and there’d be a camp put up on what we call Lina fields, on be the Punch Bowl.

What’s that name Fred?

R- Punch Bowl..

Yes but…

R- Lina, Lina field we allus called it.

[What is now the Punch Bowl Inn, just over the crossings at Earby, used to be Lina Laithe and Farm.]

Aye.

R- They used to, that seemed to be a half way do for a lot of soldiers. They’d come marching through Earby and then they'd put up there all night and we used to go on after school and they'd happen give you a plate full of broth or sommat like that.

Aye, that's it.

R- It were, we were really interested you know in 'em. Some on 'em would happen give you a drink of tea out of their mucky old enamel mug and that. You were really, though you were sommat when you’re stood there you know, and they were coming marching down and band playing you were going yourself you know, your feet were going. Many a time they were

(750)

(40 min)

coming down when we were going to school and eh, I wish we could walk at back of ‘em instead of going to school. We daren’t, we'd to go to school. And I can remember a lot of that you know, when it had been on a bit, you'd be going to school, one of the lads says “Me dads got killed”, you know. And another would happen say “Me mothers got a telegram, me dad's missing.” And it were every week there were sommat like that as you went to school but me father never had to go [reserved occupation]. There were three of 'em working at this mill where he worked during war, B and W Hartley's, Brook Shed, and there were only three tacklers and two got called up and it left me father then. And they put a lad, somebody on mugging about and they stopped a set of looms. So me father and this mug about had to run all the mill then. But one set were stopped. As time went on I can remember going down to the mill when school loosed. Some mornings, eight o'clock, I used to have to run to the mill. Me mother had fried him some bacon and egg or sommat like that and I'd to run to the mill wi’ it afore it got cold. But I were fairly lucky that way, he never used to say owt didn't boss about me going in and many a time a weaver 'ud happen want a bit of an errand running, and they daren’t go out and I’d happen go to shop for 'em. They'd give me an ha’penny for going. It were a real do were that,

(800)

Aye, which were a good do then.

R- It were a good do.

Aye.

R- And then as I got a bit older, happen about eight, if there were any things to go to the blacksmith, Mr Hartley used to say will you take these to the blacksmith. Well with me going to the blacksmith with this here, I got to stop there and watch the blacksmith mend 'em.

Were that in the same shop. Well, it was.

R- Where Stanley Whitakers is now.

Aye? Stanley Whitakers garage?

R- Yes that were the main,

Oh that were the blacksmiths were it?

That were the main blacksmith, Dodgson’s smithy.

Dodgson’s?

R- Yes.

Aye.

R – Aye, you felt you were a man when you were getting to do them things.

Aye. Can you, now wait a minute, no you'll not be able to. You wouldn't remember Henry Brown's having their workshop at…

R- Albion Road...

Albion Road would you?

R - Albion Street, yes.

Aye. 'cause that would be there when you were a lad.

R- Yes.

Henry Brown would start up there, wouldn't he?

R- That's it aye.

R- Aye it were at the bottom end of Albion Street and it were up to Albion Mill and shafting came through out of mill.

That's it.

R- To run it in there.

Yes, aye.

R- Aye I can remember that.

Anyway, you had piped water. And did you have a stair carpet?

R - Yes.

How was it held down Fred?

R- Them brass stair rods.

Aye, everybody had brass stair rods.

(850)

R- Aye and they used to polish 'em at spring cleaning day.

Aye. Who polished 'em, your mother?

R- Me mother aye.

And did the neighbours have a stair carpet an all? Did everybody have a stair carpet?

R- They had, they had up there up Lincoln Road. They were all just, you know, reasonably well off.

Yes, that's it.

There were nobody out and out poor.

How about curtains Fred?

R- Aye we had th’old lace curtains and paper blinds.

Aye, they were popular then weren’t they. Very popular, spring blinds, weren’t they aye.

R – Yes.

Can you remember any families not having curtains, you know, not having what we call proper curtains?

R- Well I could in Earby but not up Lincoln Road where we were.

Aye.

R - But you got, not belittling the place, but they used to talk about Dock Yard and up Muck Street, well they were same..

When you talk about Dock Yard and Muck Street what did you call them. I’ve heard old Earby folk.

R- Dock Yard..

Yes.

R- It were Albert Street. Facing what were Johnsons mill.

Yes.

(900)

R- It's pulled down now. Well there were some big families on there and I know there were one family, and they’re all grown up and all decent respectable people and I said to one of 'em “How did you used to sleep at your house?” He said “North, South, East and West in one bed.” [Laughs]

You can work that one out for yourself can’t you.

R- Aye.

(45 min)

And did the women in the street donkey stone door steps?

R - Aye.

All of em?

R- Yes.

Any of 'em do the kerb stones?

R - No, no.

Some people used to like. I tell nearly everybody this when we get to this question. I was once told, I can’t say whether it's true or not, that there was one street in Dukinfield that used to be famous, they used to blacklead the tram lines. They used to donkey stone the kerb edge and blacklead the tram lines. Now whether that’s right or not I don't know but I can imagine it you know.

R - Oh yes.

And how was the house lit Fred?

R - Gas.

Yes, were they fantails or mantles.

R – Mantles in the house and them like fantails in the kitchen.

Aye.

R- There were nowt upstairs. They were only in kitchen and..

So upstairs were candles?

R- Candles.

Aye. And not so often.

R- Oh now candle had to be blown out when you got into bed.,

That's it.

R- There were no wasting candles.

The ones with the mantles, were they incandescent?

R – Incandescent mantles.

Was there any covering over them or were they just bare mantles.

R- Well you used to get a globe now and again and they just, you know, they seemed to crack..

(950)

Aye.

R- Break and then you'd be ‘bout globe for a while.

Aye.

R- And then eventually they'd have happen saved a bob up and buy another globe.

Aye. How about moths coming in and breaking mantles, can you ever remember that happening?

R- Aye, they used to come in.

Aye flying in.

R- It were a tragedy were that!

Aye fluttering round the mantles.

R - Yes.

Aye. Can you remember anybody ever fitting a new mantle? You know when you fitted a new mantle? Did you like to watch it go black and then come up white?

R- That's it, aye and then it used to come up white.

Aye.

R- They were like woven weren’t they.

Yes they were, yes. Tilley mantles are exactly samey you know, for Tilley lamps now.

R- They were soft and, aren’t they.

Yes there like silica or sommat like that.

R- Silk, yes.

Did you ever have electric light in that house at Lincoln Road?

R- No, no.

Not while you were there.

R- No.

How did you get rid of the household rubbish Fred?

R- With the old ash pit. They used to put it in the ash pit and they used to come round and shovel it into a box cart.

Now, ash pits, there's a lot of people won't understand that nowadays. But the ash pit was like next door to the closet wasn't it, outside.

R- Yes, aye.

And everything that wouldn't burn got chucked in there didn't it.

R- Got chucked in there.

(1000)

But am I right in saying that you didn’t used to chuck stuff in there that would burn?

R - Oh no.

Because it would get to smell wouldn’t it.

R- That's it aye, all t’salmon tins and that, they were all burnt before they put 'em in. Well we did before we put ‘em in the ash pit.

Yes.

R - Any potato peelings, tea leaves, it all went on the fire. You'd to economise that way, damp fire down a bit.

Yes, not only that, but it destroyed a lot of stuff that wouldn’t be on the tip attracting rats and what not.

R- That's it.

Because that's biggest thing there is nowadays you know with central heating.

R- Yes aye.

These tips are full of stuff that attracts rats.

R- That's it aye.

(48 min)

SCG/09 April 2003

7,994 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 78/AH/02

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 7TH OF SEPTEMBER 1978 AT 14 STONEYBANK ROAD, EARBY. THE INFORMANT IS FRED INMAN, TACKLER AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

The first ten minutes of this tape are blank, owing to the fact that your interviewer made a stupid mistake and was recording for ten minutes with no input but I've left things exactly how they are and gone over some of the questions again without telling Fred actually what had happened until we finished the tape. So from here if you wind on about ten minutes you'll come to the beginning of the tape.

(132)

(9 mins)

R - We used to put it on and then we used to polish it off, wipe it off and polish it up. It were all elbow grease.

Aye.

R- And then there used to be the old ornaments, horses, bronze figures of horses of various descriptions. If you only had 'em today they'd be worth a lot of money.

Yes.

R- The old silver photo frames. It were a hard life for a woman there were no doubt about it because I’ve seen her many a time, she’d be all night, you know, mending me fathers overalls. Not at Sunday of course, happen at Saturday, she didn't go to the pictures. She couldn't go to pictures she had me father’s overalls to mend or sommat like that.

Aye.

R- They had to be just so for Monday morning.

Aye.

(150)

R- Because they wore like overalls and waistcoats and a blue jacket in them days. Sometimes they'd have fustian pants, fustian waistcoats and you got these fustian pants. If it were fine me mother used to lay 'em down in yard and get long brush and scrub 'em, get a reight lather on. [Fustian is cotton corduroy]

Aye. But like all the other washing would be done, well in the old days with a dolly tub and posser.

R- That's it.

And when she got her patent washing machine.

R - Oh aye.

They'd be done in there, She'd think it were a great day when she got that machine, wouldn't she?

R - Oh it were a marvellous thing were that aye.

Aye. Cast iron frame were it?

R - yes.

Aye.

R- I can remember, things come back to you don’t they.

Yes.

R- The kitchen window pushed up at the back, me mother washing at the sink under window. I stood on a buffet in back yard, that's why I never like standing on a buffet now. I fell off it and I bit me tongue and she had to leave her washing and take me down to doctors. It were just at the bottom of the street, there were a doctor. And I always remember he said “Well I can’t sew it.” It must have been badly cut. He put some nasty stuff on, I can remember that and I hadn’t to have any dinner and I hadn’t to have any tea and I hadn't to have any breakfast. And I had to just wet me lips or me mother had to wet me lips for me. It healed up and me mother said it bled a lot and I can remember going down with a hankie on and it were all full of blood.

Aye.

R- Now today like, I suppose they’d have just popped a stitch in it.

Aye.

R- It weren’t long of healing up though.

You say you were stood on buffet outside window. What were you stood on the buffet for, taking 'em through to wring 'em?

R - No, I were just watching me mother.

Yes, I see.

R- Just watching her.

Oh, she wouldn't have you in the kitchen, there were too much going on?

R- Well, I suppose it were a grand day and I were playing in the yard and I must have climbed on this buffet and were watching her.

Aye, and Stephenson’s polish, nobody else has been able to remember the name of that you know.

R- No.

R- Yes. It were Stephenson's, it were in a bottle and the neck went up and it had like a mushroom cork on.

Aye.

R- Yes.

Aye, and funnily enough, you know you were on about irons. There must have been more sorts of flat irons than I've had hot dinners. Everybody had a different sort.

R- There were some, they had a heaters, blocks of iron you put in the fire and then you put them into the iron.

(200)

That's it aye. That's what, when I say a box iron, that's what I think of as a box Iron.

R- Mm, oh yes, aye.

You know, they had a little door on back.

R- Aye that's it and you just shoved ‘em in.

And you just had a, well, you could have 'em in oven couldn't you, blocks of cast iron and just pop 'em in. [I was wrong here. Usually they were in the fire and used red hot.]

R- That's it, cast iron. They used to sell 'em at hardware stores, like ironmongers, ‘cause they used to burn away eventually.

Aye, yes.

R- Keep getting red hot.

Did you ever used to keep a couple of bricks in the oven for putting in bed.

R- No, we never did that.

No. My grandma used to always have some in and she used to scrub these bricks and she used to have these bricks in the oven and she used to wrap 'em in a piece of cloth and put 'em in bed you know. They were in the oven all day.

R- Aye.

With the cat. The cat used to be in oven and all. I can always remember that. Anyway, so your mother used to think a lot about her sideboard.

R - Oh yes.

That's it. And did you and your brother ever have any jobs to do round the house?

R- No, we never had a lot to do other than, me father had an allotment and we used to have to go on there. That were the main thing.

Aye.

R- That were all. As regards same as getting coal in or chopping wood, we never did owt of that.

Running errands?

R- Well we used to run errands but not a reight lot cause when me mother went shopping she, well they used to put a shopping order in and they used to fetch it round. She used to go and happen leave it at Monday and it would come at Monday night would the shopping order.

(15 mins)

What were that, Co-op?

R- No, it were what they called Albert Bailey's, a village store at the bottom of Stoneybank.

Aye.

R- We did used to go to the Co-op occasionally. Like we were members there but we used to get main of stuff at Bailey’s. You could get shoes there or clothes there owt you wanted, a little village store. We used to call there when we were going to school, have you any broken biscuits.

Aye that's it. You don't get them now. You buy 'em now in a packet don't you.

R- Aye that's reight.

In the old days you used to get 'em cheap after. [When I had the shop at Sough we sold biscuits loose out of the tin and there were always some broken bits in the bottom.]

R- Happorth (Halfpenny worth) of broken biscuits.

Aye, modernisation Fred, you get 'em in packet now.

R- Aye it were a twist were’t packet job weren’t it.

Aye. We were only talking about that the other day. In the old days you used to get all whole biscuits and broken ones used to get sold afterwards.

R - That's it.

But now if there's any broken ones they’re in the packet. You know yourself you can open a packet many a time and half of ‘em’s broken.

R - Aye you do.

Anyway, course you and your brother, there weren’t a lot between you so you wouldn’t be helping each other to dress or anything like that because you were about the same age. Did your father do any work in the house, you know, like mending and decorating or anything.

No. No he didn't do owt.

He never did anything in the house.

(250)

R- No. In them days they'd happen have Pratt. He were like a painter and decorator. He’d come up and he’d knock at doors, so and so wants painting, back and front, and are you owt in the way? And he’d get, we'll say there were fifteen houses up the row. He might get ten houses what were all in a mind to have it done. And then you know, they used to burn it off, they were all grained in them days. Burn it off and work up the street and then back you know. It took a lot of time did graining, didn't it. And then probably the following year he’d come round. “Do you want it varnishing?” And you used to get it varnished, it lasted ages. Back, when he used to do the back, well it were just green paint or sommat like that. That were a popular colour weren’t it.

Aye. Still is.

R- I don’t think me father ever painted at all and never did any papering.

And did he ever do anything like cleaning or cooking or…

R - No.

Bring coal in or owt.

R- He’d light the fire of a morning when he got up you know.

He’d be up first.

R- Oh, five o'clock or sommat like that.

Make your mother a cup of tea would he?

R- Well he’d leave the kettle on the bar.

Aye.

R- He had a little pan, it’d just hold about a cup full and a half of water.

Aye.

R- Measure three quarters of a cup full into it and put it on the fire. By the time he’d getten washed and ready it were boiling.

That's it, yes.

R- And then he’d fill the kettle and then that would be put on the hob.

Yes, ready for your mother when she come down.

R- Aye, when we got up, me mother got up and we got up. There were a kettle nearly boiling for breakfast.

Aye. That house in Lincoln Road, did your father own that?

R- Yes.

Have you any idea what he paid for that house when it was new?

R- Yes. I've heard him tell. They were only £195 and he got a vestibule put up and it might have been that cistern cupboard doing, it were £200.

When you say a vestibule, you mean like a partition in the hall between the front door and house like.

R- Aye well front door opened straight into the house.

Yes.

R- And they just got another extra bit of a partition fit in.

That’s it yes. Just to stop draughts and what not aye.

R - Aye well..

£195..eh.

R- Aye £200. When they sold it houses had gone up. What did they get, about £350, sommat like that.

Aye.

R – After the first war.

Yes. Course I mean he’d have more to pay for the one he were buying so it makes no difference.

R- Oh yes.

(300)

Did your mother ever do any work in the house to earn a bit of money like taking sewing in or anything?

R- No, she used to look after a youngster now and again.

What, a bit of child minding?

R- When his mother went to work me mother would happen go into the house, you know. She'd go to work at may be seven o'clock and me mother used to go in about quarter to eight and get him up and fetch him into our house and make his breakfast and off to school.

That's it, off to school. Aye.

R- And then at four o'clock when school loosed he’d come to our house while half past five while his mother came home.

Yes. And of course it were fairly common weren’t it Fred in those days for children to go to school a lot earlier than they go now. [at a younger age]

R- Oh yes.

For that reason, for parents that were working in mill.

R- Aye and at one time they [weavers] started at seven [usually 06:30] didn't they and then they finished at half past eight, half an hour for breakfast. Started again at nine and some parents, if they were handy, they used to run home and get their children up and wash 'em and feed 'em and off to school and then…

(20 mins)

Back into the mill.

R- They’d no time to get any breakfast themselves.

Aye,

R- But I mean it were only about a shilling a week like. Doing all that. Going and getting 'em up. Sommat like that.

Yes, that's it. Well it were only about half a crown [2/6d.] for child minding for a week weren’t it.

R- Yes, that were it aye.

That seems to have been the usual rate you know. I mean really I should be asking you but I mean we've got that far on now that you know. It seems to have been about the usual rate that, half a crown a week for child minding. Can you remember any other women in the neighbourhood doing anything like taking in washing or sewing?

R- Oh yes, aye. Aye there were one women up street she used to take sewing in. I forget her name now but she used to, you know, make shirts and plain sewing, nowt fancy.

That's it aye.

R- Biggest part of 'em, same as me mother, she’d a sewing machine and when we were youngsters she used to make us suits and all that. It were later on afore we ever got a suit from shops.

Aye, what sort of a machine were it, can you remember?

R- It were an old German one. It weren’t a fancy machine, it were just a plain sewing machine.

Aye, Frister & Rossman?

R- I couldn't remember. No.

No. And that house on Lincoln Road.

R- Lincoln Road.

Is it still standing?

R- Oh yes, aye.

What number were it?

R- We lived in twenty one that were like a four roomed house.

Yes.

R- Oh yes they’re still standing. They've been modernised and they’re like owt else now, two up and two down. They’re worth more than big ‘uns.

Yes, aye.

R- Oh they’re selling for £5,000 now.

Make your dad laugh wouldn't it.

R- He’d have a fit, he would.

Reight, favourite subject with you Fred now, food.

R- [Fred laughs] Food.

Aye food, ‘cause I know you like your food. That’s why you’re so healthy. Now, what did your mother cook on. Well, I know that questions on here, but I mean, in the early days she were cooking on the range weren’t she.

R- On the fire. She cooked on the range until she got a gas oven.

That's it. That would be on the top bar for pans.

R- Yes.

And in the oven.

R- And oven.

Aye.

R- Aye you put, there were a thing fell down you know, over the top of the fire.

That's it. [This was a cast iron grate hinged at the back or the side of the fire which could be folded down for cooking. There was often two round grates which were pivoted on the front bar, these could be swivelled round so they were over the fire. My grandmother used to put pans straight on top of the fire.]

R- And they used to put the frying pan on there.

Tell me sommat. Something that's struck me, there was a back boiler wasn't there?

R- Yes.

And there was a side boiler as well was there?

R- Yes.

So did the side boiler ever get used?

R - Well mostly for fire wood.

That’s it Aye.

R - To keep it dry.

Yes that’s it. It just struck me, you know, with having a modern boiler, which it was then, a back boiler were a fairly modern thing to have then.

R- Aye. Because you’d have to fetch a bucket out of what we called the kitchen and teem it into the boiler.

Yes.

R- So we never bothered with that with water.

And when did she first get a gas stove? Can you think? When can you first remember a gas stove?

R- Oh I’d be about eight happen. It were a big clumsy second hand thing what me father had bought.

So that's cast iron.

R- Cast iron, it weighed a ton, took two of ‘em to fetch it.

How did Ernie describe it, wait a minute, Ernie described it, they had one just the same. Bow legs on it, I could just see the thing you mean. He said “It stood there in the corner with its bow legs and it looked as if it would take any amount of punishment.”

(400)

R - Aye, it did, aye.

That would be about it wouldn’t it.

R- Oh aye they were a solid job, I mean but when a woman had baked in a side oven all her life up to then, they took a bit of getting used to did a gas oven.

Yes.

R- But eventually she got used to it and then I think we got the oven door done up. You know, they used to blister with the heat and I think we got it done up and it were like a lovely range then because we gave up using it and used the gas oven.

That's it aye. And them old ranges, every so often you had to take all the little doors off and brush all the flue's out on ‘em didn’t you.

R- Oh that's it aye.

Who did that, did your mother do that?

R - Me mother aye. Aye me mother did that before she started baking.

Aye. Did she do that each week before she started?

R- Yes. Every week they were done.

Brush all the flue’s out aye. Do you know I can remember me grandma doing that.

(25 mins)

R- Aye.

There’s no question about that on here. I’ll have to speak to Elizabeth! And did she make her own bread?

R- Yes.

Always?

R- Always.

Yes.

R- Aye and sad cakes.

How much did she make at once?

R- Well I don’t know, she made enough to last all week anyway.

Yes, that's that I mean, did she like have one good do of baking for a week.

R- One good baking day.

You said, that were Thursday weren’t it.

R- Yes.

Thursday were baking day, aye.

R- They used to be left out for so long and then put into th’old stone earthenware bread mug. Aye. And they used to keep while, you know, it would keep a week.

Where were the bread mug, in the kitchen?

R- Pantry.

Pantry.

R- We had a pantry.

That Would be a stone floor an all.

R- Yes.

Stone shelf?

R - Yes.

Aye. Did she bake cakes, you know, sweet cakes.

R- Yes.

What sort?

R- Oh sometimes they were them there, I never did used to like them but me father and mother did. Caraway seeds in.

Seed cake aye.

R- Eh, I could never stick them.

Aye.

R- She’d make some of them for herself and me father and she'd make me brother and me just ordinary happen. A few currants in sometimes and sometimes just plain ‘uns.

Aye. Fruit loaf?

R- Fruit, and what is it, Eccles Cakes, scones. Oh it were a real baking. It were nearly a crime to buy owt like that when you were at home, that were your job when you wore stopping at home.

It were thought so weren’t it. Bought cakes were…

(450)

R- Oh aye.

It was an indictment...

R- Oh yes.

Bought cakes aye. Did she bake pies?

R- Yes.

Fruit?

R- Tatie pies in the oven you know, and just what...meat and potato pies. But when we were having a meat and potato pie she allus used to have to make a small one for me brother. He didn't want any meat in.

Aye?

R - He were a vegetarian reight from being a child, he didn't like meat. And she allus made him one, potatoes and onions in a little dish wi’ a crust on. On his own.

Aye.

R- And then he’d only eat tongue, that were the only meat he’d eat. You know, when we were having us dinner at Sunday he’d have roasted potatoes from round the meat, mashed potatoes and gravy but no meat. Sunday tea time if were having cold meat he’d have some sardines, aye.

Aye.

R- But he were called up into the last war like and when he come back [laughs] he’d eat owt. Aye. He were no vegetarian then.

There were no vegetarians in the army! Did she make jam?

R- Yes aye, and I can remember one time, jam pan [on the fire]. “I’ll just give it another few minutes.” She'd been stirring it and testing it. I’ll just give it another few minutes and then pop!, soot. A soot fall. All her strawberry jam spoiled. It were a tragedy were that.

Aye it would be. What were that, a brass jam pan?

R- What wi’, you know, the price of strawberries and sugar, it set her back a long way did that.

It would, it would, that would be a disaster.

R- Aye.

How about pickles?

R- Aye they used to make pickled cabbage mostly, red cabbage.

Did you dad grow cabbage?

R- Yes. And onions, you know, sliced up in vinegar. We used to get a lot of them to cold meat.

Aye. How about little onions, shallots, did you used to pickle them.

R- Yes, aye.

Who topped and tailed them?

R- Me mother did all that.

Oh, she did it! Aye, your dad were bringing you up the reight way, he didn't have you, [Stanley laughs] I can see it.

R- Although I will say this, we used to watch me mother a lot, it stood us in good stead. I could have done it.

(500)

Yes.

R- After we got older we could do it.

Yes. Did she ever make any wine or beer? Home made wine?

R- Aye she used to make home made stout.

Stout?

R- Aye. But she never made any wine or beer as we know it today.

No.

R- It were some kind of stout. It were very lively stuff and you'd only to have a drop and I think meself she'd happen make it more for a medicine for us you know. Not as we ailed owt, but for a bit of kick into you.

Yes.

R- Oatmeal stout it were.

Well you see, the next question on here is did she make her own medicines, and if so, what kind. Well I mean that's…

R - That were one of 'em.

I mean it's like making egg nog, you don't make that to drink, you know.

(30 mins)

Like you make that for a medicine don't you. I used to make that when I were down at the shop. Did she make anything else like, you know as a medicine?

R- No, me father used to do that. Boil liquorice and aniseed., aniseed it were. A drop of aniseed in.

Aye.

R- Linseed, liquorice and a drop or two of aniseed drops in. He used to warm it up on the fire and mix it all up and then he used to strain it into a bottle and that were cough mixture.

Yes and good stuff an all.

R- Good stuff an all aye. And then he used to chuck the linseed ower to the hens at bottom of street, he didn't waste it, he used to chuck it to the hens. They used to gobble it up.

Aye. It wouldn't be bad taking either that.

R- No.

Linseed, aniseed and liquorice, it would be alright that. What did you usually have for breakfast during the week.

R- During the week. Porridge to start wi’ and then happen a couple of slices of toast.

Porridge. What were it, were it salt on it or..

R- Sometimes oatmeal and sometimes Quaker Oats.

Yes, but did you put salt on it or did you…

R- No, milk...

Milk.

R- Milk and sugar.

Oh you were doing well. Scotsmen would say you were ruining it you know.

(550)

R- Aye. Then, happen at Saturday, me brother wouldn't eat eggs, but me father would happen have a boiled egg and he’d knock the top off and he’d give me the top. He’d knock a big top off it like and I’d get that. I'd done well, I thought it's a good job me brother doesn’t like 'em.

Aye or else your dad would....

R- Aye, 'cause he only had one every fortnight.

Aye. And what did you have for Sunday dinner?

R- Oh It were allus a real dinner, mostly sirloin and potatoes done round the sirloin, you know, in a meat dish. Yorkshire pudding. Finish off with rice pudding. There was no such thing as finishing off wi’ a cup of tea or biscuits or owt of that. You'd finished when you'd had that. And you'd had enough, you didn't want anymore when you’d had that.

Yes.

R- And then at tea as I say, there were happen cold meat and stewed prunes and custard.

How about dinners during the week? Well we’ve heard about Monday dinners haven’t we. It could be resurrections.

R - Aye, that were resurrections mostly.

Washing day aye.

R – Aye. We might have had a bit of fried bacon and some fatty cakes at Tuesday. And then at Wednesday it would be stewing meat. Then at Thursday, sometimes it were a bit of steak. Then at Friday it were sausage. It were fairly consistent all the time,

Aye. Any particular sort of sausage?

R- Eh, it didn't matter whether they were pork or beef, thick uns or thin uns. They were all alike.

Aye, of course sausages were sausage in them days weren’t they.

R- Aye they were. They were a meal weren’t they.

Aye, aye they were that alright.

R- And teemed the fat what came out of 'em on to your potatoes. You know, mashed potatoes and teemed fat on 'em.

(600)

Have you noticed nowadays you've to put fat in with sausages?

R - Aye.

It doesn’t come out of 'em.

R- No.

No. There’s something funny somewhere about...

R- I mean, the skin's is that thick you can’t get through 'em.

There’s something funny about sausages nowadays Fred I think. I can tell you a little tale about that. You remember I used to have that shop at Sough, you know, next to the mill there, next to Sough Mill.

R- Did you?

Aye. And I once sold a woman some sausages one day and she come back a couple of days later. She said “Them sausages you sold me t’other day". I said “Did you like 'em'?” She said the sausage were alright but by God the skins were tough!” I said “Hold on a minute, which sort did you get?” And she got these frozen sausages, I said “You daft beggar! They were covered with plastic! You're supposed to take that off. You didn't eat it did you?” She says “Aye. We ate them, I ate most of mine. I don't know what Jim did with his!”

[Laughter from Fred]

Aye. Complaining about the skin being tough, they were covered with plastic, she'd eaten the lot. Anyway, yes, what did you usually have for tea during week? I don't mean Saturday or Sunday.

R- Well it were mostly treacle butties and jam butties.

Aye.

(35 mins)

R- At tea time. There were nowt special prepared.

And Saturday and Sunday ‘ud happen be a bit better do.

R- Oh yes aye, you got a better do then. That were weekend. But through the week, as I say, it were mostly that. Unless it were new potato time you know. Digging potatoes up off the garden, happen have some new potatoes with some butter on. It were allus butter when they could get it, it were butter.

Aye.

R- She didn't use margarine.

Aye. That’s one of the things later on actually, about margarine. Anyway, we'll get round to that. Did you have supper before bed time.

R- If we did it were pobs.

(650)

Aye. Well, I know what pobs are but you'd better tell us what pobs are because other people might not know.

R- Well it were crusts of bread broken up and scalded with the water squeezed off, sugar put on and some warm milk.

That's it.

R- You had a pot full of them to go to bed off. And they didn't do you any harm.

That's it, do you know I still like ‘em. I still like bread pobs.

R- Aye.

I do. I’ll tell you how I like them, me mother used to do them. She used to toast ‘em.

And then put ‘em in milk and they make the milk taste a bit nutty you know, when they’re toasted.

R- That's it, aye.

Aye. I still like ‘em toasted, but I were greedy, I used to butter 'em before I put ‘em in.

R- Aye. Well, if there were any bread left at tea time and it, you know.

Yes wi’ t’butter on...

R- Butter on. It used to lie on top of the milk aye.

That's it aye. I’ll tell you what, it doesn't do you any harm. I still like it. I do. I don't know.. I’ll tell you when they used to give me bread pobs, if I'd been poorly you know. If there were owt wrong with me.

R- Oh yes aye. Build you up a bit.

Aye, that were it aye. And pepper on an all. I used to put pepper on. Of course I've always been a bit of a bugger, I put sugar on potato pie! I’ll tell you what Scotsmen do, I’ve seen 'em many a time. Scotsmen will get a bowl of soup, and what you really should do is sprinkle oatmeal in it, but if they were getting a bowl of soup in a cafe or anywhere, they'll have a couple of digestive biscuits with it and break them up into it and then a bit of sugar on an all and mix it all together. And I’ll tell you something about it, soup with sugar in like that, by God it can warm you up. It can get you a sweat on Fred, it can.

R- I love soup.

Oh aye. Anyway I shouldn't be telling you about that because we're trying to find out about you. Well you've already said that you had an allotment haven't you. That your dad had an allotment.

(700)

R- Yes.

And what sort of stuff did he grow on there?

R- Well it were mostly sommat to eat, happen just a few flowers to just set it off a bit but potatoes, cabbages cauliflowers, Brussels, beetroot, all the popular things and he were fairly successful wi’ it an all. He spent a lot of time on it. Potatoes, he used to get 'em up and fetch 'em home and they used to last us a long while. We’d have one of them old apple barrels, he used to put so many potatoes in and then scatter some flower of sulphur on them.

Aye.

R- And then some more and some more flower of sulphur in. He said it kept 'em, they didn't go foisty. [fusty, mouldy]

No I can believe that.

R- They lasted us a long while.

You’d say he were a good gardener then your dad.

R- Oh yes, aye he were extra good.

Aye, did they have a horticultural show then in Earby?

R - Yes.

Did he have a do at them?

R- He used to do a lot of winning.

Aye that's it. Had he a favourite for competitions.

R- Onions. Onions, them were his favourite.

Aye.

R- He could grow onions, and I don't know why. I don't know owt about gardening to mean owt but that's my favourite. There's nobody grows a better bed of onions, just ordinary, as what I do.

Aye.

(750)

R- I don't make a fuss of ‘em like somebody what's showing them and all that. You know, make a special do of a few of 'em and like that, but I allus have a good do. But last year sommat went wrong with them and they nearly all split and they went mildewed inside.

Aye. There were a lot of bad onions last year.

R- 150, I had 150 and I don't think I got 40 out of all lot.

Aye. No, I remember, ‘cause I'm no gardener. I think actually I might get round to gardening later in life. I can see the point in gardening. Did you eat all the stuff that come off the allotment, or did you sell any of it?

R- Oh he used to sell a lot of pea swads. [Pea pods]

Aye.

R- Aye and lettuce and he used to give part away to folk you know, what weren’t happen in reight good circumstances.

That's it aye.

(40 mins)

R- Give 'em a bucket full of pea swads and half a bucket full of potatoes and they were reight then for a good meal.

Aye, yes.

R- Beetroot, I never used to touch beetroot and carrots then. And now I love ‘em.

Aye.

R- Aye. It were funny, I wouldn't eat beetroot.

It's been a bad year for carrots this year an all. I don't think I've had a good carrot this year.

R- No.

No. And last year I thought it were a good un for carrots, by God there were some nice carrots. I’m talking about carrots you buy like, you know. But this year I don't think I've had one good one. And Vera can cook vegetables you know, she just chucks 'em in, warms 'em up and pulls 'em out and that's how they want to be isn't it.

R- Aye.

They don't want boiling for three hours. Anyway, did you have any hens or anything like that. Goats or…?

R- We once had about three hens in the back yard. I think it were when 14/18 war were on but I think somebody must have said, you know, one or two of 'em had 'em in the back yard. Somebody must have said sommat and we had to clear 'em out, they hadn't to keep them.

No. Public health.

(800)

R- Probably aye. But I had a laughable do with Mr. Hartley what were the manufacturer. He had a garden aside of us and they lived in a big house, nearly aside of this allotment and he had some hens in a pen at the end of his house. And he were going on his holidays one time so he says “I have a job for thee.” He said “Look after my hens next week and you can have all eggs you get and sell 'em to your mother, tha’ll be well off.” So, a good do were this, he only had about ten hens and there were six eggs first day, happen five next and back to six. Six days I were taking these eggs home, I weren’t selling them to me mother. Me mother were getting them and then when he came back, “Well how many eggs?” I'd to put it down on a piece of paper. “My, tha’s had a good do hasn't ta! Tha’ll have made a bit of money?” I says “No, I didn’t, I gave me mother ‘em.” He said “Tha’rt a good lad.” Well time comes round again, he says “I’m going on me holidays, I want you to look after the hens, same terms.” Oh I were rubbing me hands, yes. When I went after school at four o'clock. He’d gone at Friday and I went to 'em. School loosed at four o'clock, there's no eggs. I thought, oh well he must not have gone while about dinner time and he's picked 'em up. Morning following I goes, no eggs. I ran home from school at dinner time and had a look, no. I went to Sunday School, that were it. When Sunday School loosed I dashed up, no eggs. No eggs at night. He come back off his holidays. He says “Hasta been marking t’paper?” I says

(855)

“There hasn't been any eggs.” “Wasn't there? That's funny isn't it? Been a poor do hasn't it? Tha’rt sure there's been none?” I says “No.” He says “I’m going to learn thee sommat. They don't lay when they’re in moult!” [Fred laughs] He give me a tanner. He says “I'll give thee a tanner.” I got a tanner off him.

(laughter from Stanley)

R- But as I got older like I could see the joke.

Yes.

R- Probably he’d tell me father about it and some of the other fellows at work and they'd had a reight...

Would that be Joe Hartley’s father?

R- Aye, Joe Hartley, that's it.

Is he still going Joe?

R- No. No he died not so long since.

Is that right.

R- Yes, think they found him dead.

I remember we once went to a do at the Albion Club [Conservative Club]and there were me and Eddie Lancaster.

R- I'll put the light on Stanley.

No you’re reight, you don't need to bother about light no because this tape’s nearly finished. I’m just trying to think, we were stood in this queue, that's it, and Joe Hartley walked to the front. Because he were a big man at the Con. Club like.

R- Oh he were.

Aye. He walked to the front of the queue and as he's walking up to the front of queue somebody said something and Eddie Lancaster chimed in and said sommat about, you know, bloody hell, Joe queue jumping. And he turned round did Joe Hartley, he said “Lancaster!”

(900)

(45 mins)

He said “I heard that” and then Eddie says “Hartley, there’s handle to my name! Use it!” I've never forgotten that.

R- Aye...

Aye he says “Lancaster!” Aye, going back to th’old days you know. Well that weren’t the old Hartley, that were Joe. Where did he have his looms, Hartley’s?

R - They were on New Road.

When you say...

R- Where Johnson's are now. '

Not Brook Shed.

R- Yes, Brook Shed.

Brook Shed, aye.

R- Yes. There were his brother had the end place, you know, where the 200 loom shop were, reight at far end. His brother had that, Thomas Henry Hartley. And then there were, B&W. Hartley, that were Bracewell and William, two brothers.

Aye.

R- And he paid Willie out and then Bracewell were there and Thomas Henry next to him.

Aye.

R - They were decent folk you know. They weren’t stuck up or owt like that.

Yes. Oh now it were just one do that Eddie had that night.

R- Oh but Joe. Oh he were a bugger were Joe. I've no time for him.

(950)

Well he always seemed a bit that way but he spent a bit too much time in pubs for my liking.