TAPE 84/SP/01

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE THURSDAY JANUARY 12TH 1984 AT THE GRANGE NURSING HOME, KEIGHLEY ROAD, COLNE. THE INFORMANT IS STEPHEN GLADSTONE PICKLES AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Recorded on Thursday, January, 12th, 1984. The informant is Stephen Pickles and the interviewer Stanley Graham. The recording was made at the Grange Nursing Home, Keighley Rd Colne.

[When I made this tape Stephen Pickles was very frail and not long afterwards he died. He had heard about the work I was doing and it was at his request that I went to see him. It was quite hard to get responses out of him as he tired and I found that the best way was to tell him what I knew and let him respond. Some instances of mistaken memory were quite clear but the reward was some quite blinding insights on topics that nobody else had covered.]

This tape's made on the 12th January, 1984 and I'm making it with Mr Stephen Pickles.

Stephen Gladstone Pickles in 1949 with his wife.

R - That's it. You can call me Stephen as well. I hate being called Mr.

Oh, thank you very much.

R - All the nurses here they know to call me Stephen. Everybody in the mill called me Stephen, me father Stephen and all me father's pals were from the mill. They were cycling pals, and mother used to call them 'The Apostles'.

I think this is the Three Apostles. Leonard Holdsworth, another manufacturer, in the centre.

Well I'm going to make you do some work now. I've actually brought some ammunition. Now as this is the first time we've talked together I think that one of the things that I’d like to try to...

R - Do you want a light on?

I don't need a light, no. Talking about light, shed a bit of light for me. The Pickles family, because I have an idea that the Pickles family like every family is interesting. One of the things that I've been doing is, as I say there's really nothing written about the history of Barnoldswick that is of any use at all.

R - You know I was going to do something but I can't get down to it. I was going to write a history myself as far as I know it concerning us, the Nelsons, the Hindleys, the Haightons, the Bracewells of Barlick and that. I haven't the energy or the time to do it now.

Let me tell you something now. Remember earlier on when you were telling me about the article for the Dalesman and I said to you, "Why don't you do it on tape?" Well what we're doing now is your history of Barnoldswick on tape.

R Well that's all right because it's in a conversation but I couldn't sit here and dictate an article.

No, I understand what you mean. I'll trigger you off. Can we have a look at the family first, the Pickles family. If you let me ask you one or two questions and that will trigger you off and if I think you're getting too far away from the subject I shall grab hold of you by the throat and stop you and we'll go back to it.

R - Well, we'll start with my father eh?

Can I ask you what your father's full name was?

R - Stephen Pickles.

And where was he born?

R - Up at, top of what is it? Newtown.

Newtown.

R - Aye, where it turns down to...

Rainhall Road?

R - Aye, it’d be in a bit of a cottage there. In 1856.

Again?

R - 1856

Now, that was your father?

R - That was my father.

Was born there in 1856?

R - Now he was called Stephen and there's always been a Stephen in our family because my father's great Uncle Stephen was killed fighting against Napoleon at Corunna. There's always been a Stephen in our family to commemorate his memory.

Now, was your father's father called Stephen?

R - He was.

What was his profession?

R - His profession was that he was a working man. They wove in their houses. They wove in their houses. All at Gillians, there was a chap called Smith who became Lord Conway and Joshua Hoyle’s in Manchester, they were all there. Now what happened was they wove in their homes- oh and Stopes. I don't know if you know Stopes at the bottom of Folly Lane. Its a house by itself and my grandfather built that house and when I say 'built it', he built it with his own lily white hands. He didn't employ anybody to build it.

Stopes House built by Stephen's grandfather.

Can I just, because I've been making a mistake here. Can I just screw you down on that one? Are we talking about, now when you say "Stopes", some people call it Stopes Gate?

R - Aye, well that's the new people that have got it and call it Stopes Gate. It's right at the bottom of Folly Lane, standing by itself next to Heather View Terraces there.

Now wait a minute, Folly Lane, let me just get...

R - That comes down from near Bancroft. '

That comes down to where - well Newfield Edge is at the bottom of it.

R - Aye, Newfield Edge is the house there. That's where Slaters lived and later Mr. Imrie lived there. The dentist.

(5 min)

Now where's Stopes House?

H - It's at the other side of the road, this side. There's the terrace houses down that side and going down to Barlick its the first house and it stands on the right by itself. Come down Folly Lane ....

It's a detached house?

R - It is a detached house.

So it's actually on Colne Road?

R - It is. Oh yes, it is.

And it's just on the right hand side and it stands up off the road.

R - It is, that's it.

That's it, I know the house you mean.

R - And me grandfather built that house.

Built Stopes House

R - With his own lily white hands, as I tell you, everything.

Tell me something, just let me leaf through me cards. These are all cards that I've got out of ... So Mrs Sarah Pickles, Stopes House, Barnoldswick, that was in 1902.

R- Aye, well yes, that was in 1902, yes. My mother was called Sarah Ann Cowgill Pickles. All on me mother's side have Cowgill in their name.

(50)

R - That's why Brian Cowgill happens to be a distant relation. The Tourist Trophy man you know [Isle of Man TT races.]. Also, there's Bishop Cowgill of Leeds. He was a cousin and he was known as the Children’s Bishop because he was very fond of children and he always had some toffees in his pocket for any children he saw. He was a Catholic. One branch were Catholics but my mother's side were Quakers. They weren't Catholics but her cousins were.

Now can I just make sure I've got this right? You were born?

R - At Heather View.

Heather View, Colne Road in 2010.

At Heather View.

R - Yes, that's the first lot of terrace houses going out past Stopes on the left. Then there's another terrace of houses all the people, the Holdens and the Dugdales, they all lived in these and the Nutters all lived in these terrace houses and I was born in the first one.

Heather View, I know which...

R - Heather View, yes.

Heather View because that's now a lodging house, because it's a big double house, that.

R - Well I was born there on 15th March 1899.

And your mother was called Sarah Jane Cowgill?

R - To, Sarah Ann.

Sarah Ann Cowgill?

R - Sorry, she wasn't. She was Sarah Ellen Cowgill Riley. She was a Riley. Sarah Ellen Cowgill Riley and she came from Thornton.

So that was your mother, Sarah Ellen.

R - Cowgill Riley - S.E.C.R. She lived at Barn Cottage there at Thornton. There's only on that side of the road going down, there's only one house that has a garage and that's because Barn Cottage has been made into a garage.

Barn Cottage in 2002.

The same row in about 1900.

That's it, that's those cottages on the right hand side of the road going downhill just past the Institute in Thornton.

R - That's it. After me mother died in 1923. She died of shock and a cancer because of me brother being killed in the First War. So he married my Aunt Lizzie, did my father and he went to live there at Barn Cottage.

(10 min)

Thornton Manor in 2009.

At that time, Sir Amos lived at the Manor House, Sir Amos Nelson and they were big pals. They both started manufacturing in the same year, in May 1881. We'd have both been going in 1981 - a hundred years and I'd planned to throw a party at the Spread-eagle at Sawley for all those that were still working for us and all those that had worked for us but were retired. Unfortunately we didn't last that long, we went out in March and that finished us and of course I couldn't throw the party. It was just two months too short. My father's out walking with Sir Amos one night from the Manor House. They were great walkers and me father was a Teetotaller and Sir Amos was a Prohibitionist so they had a lot in common. Roundell, who used to own the Gledstone Estate and was M.P. for Skipton at times, he was a Prohibitionist. He was so strict, they had what was called 'Local Option' and he closed all the pubs on the Gledstone Estate. There wasn't a pub between Gisburn and Skipton.

There used to be a pub in West Marton.

R - Well of course there did. And there was the Pub at Elslack., He closed every one down. He wouldn't have a pub on the estate would Roundell. So they were all closed down. Of course that suited me father and Sir Amos because, well as I say, my father was teetotal but Sir Amos was worse, he was a right prohibitionist, he’d have done away with drink altogether like America did.

(100)

R - Anyway, he was walking out with him was my father and Sir Amos says, "Stephen," he says, “You don't want to be paying me rent for that cottage. Why don't you buy it?'” You know it's a beautiful cottage with this barn and a lovely, gently sloping garden facing South. Goes right down oh a long way down. He said, “Oh I will buy it off you, Amos, if it's cheap enough." Sir Amos said, Well, how will £130 do?" So me father thought it were cheap enough, £130, so he bought it. Well, it's been sold this last year for £24,000.

That, of course, would be in 1880 when....

R - No, no, no it wasn't. It was in 1930.

Aye, of course because we're talking about after. We're not talking about the days when they were starting up at the same time. We’re talking about years afterwards. It was when he married Auntie Lizzie.

R - I was friendly with all the Nelsons, Sir Amos, well I was fairly friendly with Sir Amos. I was friendly with his sons. He had three sons and two daughters and I was friendly with them all. I was very friendly with Harriet but there again was a bit of a story. Harriet, his second wife, you know, Harriet Hargreaves. Hargreaves had the house on the corner [in West Marton] because he [Harriet's father] was the estate agent for them. Penny Nelson went to live in it later. Back in the 1920s Harriet was engaged, she was a bit older than me, she was engaged to a very smart lad from the Midland Bank at Barlick. He really was a handsome lad.

(15 min)

She was engaged to him but he jilted her. So just after the First War, you see, there was a lot of dancing going on and we danced like mad night after night. I know one week we had five dances on in the week. The Institute at Marton, there was no license you see because it was on private land. They'd dance till five o'clock in the morning and it was all right. So anyway, I talked to Harriet and she'd said how upset she was about this and I said, well never mind Harriet you can come with us dancing. Anywhere we go, Colne, Nelson, Burnley, Earby, Barlick, Marton, anywhere and we'll take you with us. So we did. Then, of course, she became Lady Nelson. So the first time I saw her after that, Sir Amos had married her. I said, "Harriet, you see how your biggest disappointments turn out to be your biggest blessings. If that lad hadn't jilted you, you'd have never been Lady Nelson today!

It's true.

R - Aye, it's true enough.

So your father was born in eighteen fifty…?

R - 1856.

At Newtown in one of those small cottages, of course that was only a country lane just round the top there then.

R - Church Street, there was all grass at Church Street. There wasn't a single house all the way down to Long Ing there. It was all grass. I've lost a lot of photographs and pictures coming here. I had a picture of Barlick and it's all green grass down to there - there was nothing.

So he was born in 1856. Now, do you know what his father did?

R - Yes, he was a manufacturer. He manufactured at Coates. At Coates Mill.

Now this is Old Coates Mill?

R- Aye, old Coates Mill that turned out to be - is it a carpet place now? Turned out to be a dairy, you know it was what is its dairy. [a bit of confusion here between Old Coates Mill and the present Coates Mill. In AWOL p. 60, it is stated that Stephen’s grandfather started weaving with a few looms in Old Coates Mill about 1850. The Cotton Famine forced them out to America and when the family came back they started some looms in Clough Mill, [see below]. So when Stephen says his grandfather manufactured at Coates Mill I believe he is referring to Old Coates. I checked as far as I could in my index and can’t find any mention of Pickles at the later Coates Mill. This fits with what Billy Brooks said about Old Coates Mill [78/AB/05 page 4] He stated that the mill was four storeys and there were looms on the top floor. His father wove there.]

Aye, it was built about 1856 wasn't it that mill?

R - Something like that. It was a flourishing time for mills in the 1850s.

Can I remind you of one or two dates that I do know aright? 1845 was when Mitchell turned Mitchell's Mill into Clough Mill; 1846 Butts, Billycock built Butts. 1854, Billycock built New Mill which became Wellhouse and then the next mill after that was what we now know as Coates Mill up at the top of the Coates Canal Bridge and that's the one you're talking about. [The more I learn about these mills, the more uncertain I get about precise dates of building so these dates should be regarded as approximate.]

R - And that's where my grandfather worked.[see above]

When you say he worked there, was he a manufacturer or a weaver there?

R - Well you might say he was a - they wouldn't have above twenty odd looms, you know. He controlled it and sold the products. [In the 1861 census Stephen Pickles of Newtown is described as ‘manager of a cotton weaving shed’. Age of both him and wife given as 37 so birth dates for both of 1824. Stephen’s father is 5, so birth date of 1856, Henry one year so 1860 birth. Mary is 9 years so born 1852. In 1851 he is noted as living on Jepp Hill and trade is ‘power loom overlooker’. There is a son mentioned, James aged 2 who disappears by 1861. Strange that as the eldest he wasn’t named Stephen.]

Like a small manufacturer?

R - Yes. Well, anyway in 1860-61, the American War of Independence. [Civil War actually.]

The Cotton Famine.

R - They closed every mill in Lancashire down. My father, who was five years old in 1861, he was the only one in the family earning any money and it was for gathering potatoes for the farmer and he said he could gather them faster because he was already on the ground. You see he was only five years old.

(20 min)

Billycock Bracewell, he was a right strict Puritan but it didn't stop him having twelve, he was like Lloyd George, he had twelve illegitimate kids. He was a right strict beggar. He wouldn't allow trains, that's when the Railways started to get going.

That’d be about 1870. [February 13th 1870]

R - Well, he wouldn't allow trains to come into Barlick on a Sunday. There’d be no trains. He was such a Puritan. Well, he wouldn't allow trains to come into Barlick.

And of course he was chairman of the Railway Company.

R - He had Coal Works at Ingleton and wood works. He had everything.

When you say wood works?

R - Aye, joinery works. He had his own trucks on the Railway. Well, we, as late as, we had our own trucks on the railway and we brought our own coal from Silkstone. But they were commandeered during the First War. We never saw them again. Anyway, we used to get a truckload of coal every time. Beautiful coal, 9d. a hundredweight.

Let me take you back to your grandfather, Stephen Pickles, weaving at Coates, at Coates Mill. So he'd be weaving at Coates Mill, small manufacturer there and he’d be living in not in a big grand house, anything like that but living in this house at the top of Newtown.

R - Oh Aye, at first because he hadn't built Stopes then.

So the next house he would move into from there would be Stopes House, up Colne Road.

R - It was yes.

Can you tell me, now he was living there in Stopes House. Now, was that your grandfather or it'd be your grandfather and your father would move in there?

R - My father [and grandfather] , then. as soon as I was born he moved into Heather View. [Heather View as an address can be confusing because it was a terrace of houses, very superior, but still a terrace.]

Now you've missed something out here I think. It's something that Audrey [Audrey Woodcock as she is known in 2002 was my secretary at Pendle Heritage and had previously been private secretary to Stephen at Long Ing. It was Audrey that told me Stephen was still alive and introduced me to him.] was telling me about. You were going to tell me what happened during the cotton famine. Your father was five years old, your grandfather's manufacturing up at Coates, it's 1861 and something happened in the Pickles family then.

R - Well, I'll tell you. In 1868 they were starving. They had nothing for years with this cotton famine. For years they had nothing except porridge made with water to eat and potatoes as an extra treat on a Sunday. They had enough of that and me father saw an advert from America “Immigrants wanted in America to be given three acres and a cow”.

Now he was twelve years old then, 1868.

R - Aye, twelve, that's right. Twelve, that's right so it was actually 1870 when he went, when he was fourteen. My Uncle Harry was twelve. My Uncle Harry lived at Walden down Gisburn Road. They all went, the whole family went, my youngest aunt was born in America at Fall River.

Now, when you say, your whole family went, does that include your grandfather as well?

R - Grandfather, grandmother, his sisters, my Uncle Harry and my father and they all went and they went steerage and the women were separated from the men. They weren't allowed to be on the same side of the ship as men.

(200)

My grandmother was pregnant and she couldn't eat the food at all. Oh it was terrible! So my father went to the first class steward and he said, “My mother can’t eat the food here. It's shocking!” He said, “We put up with it but she can't.'” He put a gold sovereign into his hand. He said, “Will you bring her food from the first class cabin?” He said, “Yes, I will.” And he did. It took them three weeks to get to America, travelling steerage. So when they got to America, my father was fourteen in 1870 and me Uncle Harry twelve. When I was eight, I was a founder pupil of Gisburn Road School in 1907.

(25 min)

When my father was eight, he was weaving. So they got to America and they never told me what the cow was like but he said this three acres was just a barren waste of land.

And where was that at, this three acres?

R - Fall River.

Massachusetts?

R- Just below Boston. Just South of Boston You know, Boston Tea Party business. It was a suburb really of Boston, they called it Fall River. My youngest aunt was born there and my father said, “We’ll never make a do here with this .....

Three acres and a cow.

R - He never told me about the cow. Anyway, because they could weave, they were welcomed with open arms and they all wove, my father, my Uncle Harry and his sisters and me grandfather and they worked from 6.00 to 6.00, six days a week, no Saturdays off, no tea breaks or coffee breaks. Just an hour off for a meal in the middle of the day. Sunday was the only day they had off and they saved every penny they earned and after two years, (they stayed there for two years) they came back to Barlick and they started again. My father said, “We’ll start again. I'll be the Manchester man, my father's too soft with them, I'll be the Manchester man.” [16 years old]

That was your father said held be the Manchester man?

R - Yes, well he worked at Clough Mills under Billycock you see.

That's interesting. Now they went to America in 1870.

R - And back in 1872. The War of Independence was over then so they came back.

The Civil War was over.

R - They could get cotton again.

So in 1872 they went into Clough and had some looms in Clough?

R - They all had four looms and me father said, “I’ll be the Manchester man.” Well, what being a Manchester man in his day meant that every Tuesday he'd go to Manchester and me Uncle Harry had to run eight looms instead of four. He’d run my father's as well while he went to Manchester and sold what they had to sell and bought [yarn] for a weeks supply.

So those looms that they were running there, they were more or less running on Room and Power?

R - Oh they were Room and Power.

So instead of having four hundred looms they just had four looms each.

R - Yes, yes. They just rented them off Billycock. [This is confusing because I didn’t know that Bracewell of Newfield Edge, Billycock, had any interest in Clough. Bracewell Brothers were in there at one time and I wonder whether Stephen is confusing the two branches of the family. On the whole, I think this might be the case.]

You say Billycock, now in 1867 Slaters bought that mill.

R - That's right, well Mrs Slater was Billycock's daughter. [This was Joe Slater’s wife, son of John who bought Clough.]

I've always wondered what the connection was there.

R - Now I'll tell you about the Bracewells now.

Just to keep things straight, because I've got to straighten all this up afterwards. 1867, now I want to go back just a little bit further and I want you to tell me something. Let me tell you what I know and you tell me where I'm wrong or where it fits in. Before 1867, some time around 1840 - 50 and I'm not sure of the man's proper Christian name but on Barlick Lane somewhere, somewhere along what we now know as the beginning of Manchester Road, somewhere between Hey Farm and down at the bottom there, there was a fellow called Slater had a loom shop there. He had fourteen looms.

(250)

R - Dick Carr Slater.

Now, then, Dick Carr Slater, he used to put out to places as far afield as Austwick.

(30 min)

R-Yes, all up and down the place.

Had his own carts on the road.

R - Old Nutter had seven lads and they were the very Devil.

Now which Nutter are we talking about - James?

R - Aye, the eldest one. There was Herbert, Wilfred, Eughtred, Randall, Rupert .. There was either seven or eight brothers and one girl and they always reckoned that the girl wasn't legitimate. And what he did to make his money, he sold Bibles and in those days he charged a guinea a time for them. He went round all the farmers.

This was James?

R - Aye, he went round all the farmers and he says, “I want you to buy this Bible.” “Well we've got a Bible, we don't want..'” “You don't want your cattle maiming, do you?”

(35 min)

Talk about Chicago gangsters! They'd nothing on the Nutters in Barlick, I'll tell you.

We’ll get round to that. Now Dick Carr Slater up Barlick Lane with fourteen looms, tell me what you know about Dick Carr Slater.

R - Well, I don't know anything except that he was the father of Fred Harry Slater and Joe Slater. I think he was the father of Brooks' wife.

Which Brooks?

A – [Robinson] Brooks, he lived at the top house just as you start to go down Gisburn Road - on the right there. Forest ...

Foresters Buildings.

Foresters Buildings.

R-Aye, Forest House.

Is that the same thing that we call Foresters Buildings? [Yes, see Emma Clark's transcripts]

R - I don't know now, you see things have altered but 'Forest House' was Robinson Brooks they called him. Robinson Brooks' house and his wife, she was a Slater. Dick Carr Slater you see. So they were a relation.

There was a Slater at about that time at Hey Farm, just behind the Dog.

R - There was the Slaters at Salterforth. They had the mills, they had the Salterforth Mills did those Slaters and two of those were - that was James Slater - they lived at Coates there. Harry Slater and John Slater both went blind, you know.

James Slater at dinner with his family. Probably around 1900.

I didn't know that.

R - Yes, John Slater went to live at Skipton. He came to the mill at Barlick, the mill was at Salterforth, that Silentnight have now.

That's it, Salterforth Mill.

R - Although he was blind, he came to his work every day.

Now let me just push the Slaters up Manchester Road. Now, Joe Slater, do you know...

R - He lived at Newfield Edge. Fred Harry Slater lived at Betty Carr Brow. [Carr Beck] That's just going past what was the hospital at Barlick. When you turn down to go to Bracewell there's a house and it's called 'The Knoll' and that's where Wilfred Nutter lived and that's where - I think it's Ann Bank that lives there now isn't it? That's it, she used to work for me.

1867, Billycock Bracewell was still alive and living at Newfield Edge.

R - Well he would be, yes.

He didn't die until 1886, I think it was. [1885 actually] No, it wasn't that it was - anyway, the thing that I'm trying to get at is in 1867, what do you know about one of the Slaters having an interest in silk spinning at Galgate Mill near Lancaster?

R - They weren't the Slaters, they were the Nelsons.

(300)

As far as I know, the Nelsons had the Silk Mill. They called it - Lansil they called it, from Lancaster, you know.

I'm not thinking about that really.

R - My wife was a Nelson, you know. [Audrey says she was Ann Nelson and they lived at Woodlands, Foulridge.]

I didn't know that. Can I tell you what I know about that. I know that this is right because I've actually seen the man's notebook. Can you remember a man called Robinson, used to be, at one time, a long way back, the manager of the Craven Bank, George Robinson? He was manager of the Craven

R - No, no.

Well, you won't because it's too early for you

R - The chap that was there when I was - was called Hitchen and that house “Raygill' was built for him. Then a chap called Blakey had it and then he [Hitchen] went and he went to live in Morecambe and Mrs. Hitchen wouldn't live there because she said it was too big for her and they went to live at Thornton in a house nearly down by the 'Love Tree' on the left. Detached house.

Ivy Mount at Thornton in Craven.

Ivy Mount. Billy Harrison used to live there. This fellow, George Robinson, in the late 19th Century was the manager of the Craven Bank. In 1867, it was John Slater went to him and asked to borrow £3,000 to buy Clough Mill. I assumed that he was buying it from the Mitchells.

R - They did buy it, it was their mill, it was Slater's Mill was Clough Mill.

Then he was asking George Robinson because this was in George Robinson's notebook that he had on his desk at the time and he's writing down the particulars as the fellows asking for the loan. Robinson was saying, he looks like a decent man, has silk spinning interests at Galgate near Lancaster.

R - Well, he could have, he could have. [Silk spinning during the Cotton Famine could have been a smart move. SG.]

But I'm wondering from what you're saying whether he was in with the Nelsons at Galgate.

R - No, no, he wouldn't know the Nelsons at that time. Dick Carr Slater, Joe Slater's father, he might have had an interest in that mill at Galgate.

I've often wondered about that because his putting out interests went as far out as Austwick and that way, you know.

R - It would be, it would be his father, you see.

Anyway, they bought that mill, Clough Mill off the Mitchells in 1867. Now, this is one of the things that fascinates me that I've not been able to find anything out about - I don't know, you might be able to tell me. I don't know what happened to the Mitchells then. I don't know anything about the Mitchells before or after then because from what I can make out it isn't the same Mitchells that are at County Brook now, it was a different..

R - No, it isn't the same Mitchells. [I later found that this is definitely true. The Mitchells at County Brook came out of Yorkshire late in the 19th C.]

But how about the Mitchells that were at what was then called Mitchell’s Mill?

R - I don't know; they were before my time, you see*

The thing that's always struck me about Clough and I apologise for keep pushing you back.

R - No, no you ask what you want. I'll tell you if I can but I don't want to make anything up, you see. I'll only tell you what I know. I'll only tell you what I know.

That's it but if I push you too much, tell me.

R - If I don't know, I'm not going to pretend I do know, you see,

It's always struck me that - I don't know if you've ever come across Atkinson’s papers. He wrote a thing called 'Old Barlick'. A fellow called William Atkinson. He's like a lot of these people that have written, if you like, a glorified diary. It's written in a very strange way but a lot of the things in it check out. A lot of the things turn out to be right. He gets some of the names wrong and things like this but it's good stuff. He says that during the cotton famine itself, you know 1861-2 ...

R - It was terrible! It affected all Lancashire, you know. You could get a cheap Indian cotton, that's all you could get but they couldn’t weave it, it was no staple.

Surat?

(350)

R - My father's nom-de-plume when he wrote articles for the Craven Herald and that and he wrote a lot of articles about Barlick and I had them all but of course, they've gone now with coming here. You could have had those and you'd have got tremendous information from those. His nom-de-plume was Surat. He wrote under the name of Surat.

That was a bit of a joke as far as he was concerned:

(40 min)

R- Yes.

It seems to me that during the time of the cotton famine 1861-2, William Bracewell, because of course with his interests with Burnley Ironworks and engineering and things like that you know, Burnley Ironworks. William Bracewell’s foundry as it was then, re-boilered Butts and Clough round about 1861-2 and it's always seemed to me that perhaps by about 1867 Mitchell was getting strapped for money. It seems to me that that was the reason why... [Later research is suggesting he may have been involved in a court case over water rights as well.] Can I just do a précis of what we were saying. 'What we’re talking about is the fact that when Billycock Bracewell died, his brother, Henry was living at Thornton at the Manor House. Billycock left all his money to the lady who became in the end Mrs. Joe Slater.

R - That's right.

The family contested the will and threw it all into chancery and she had to go and live with Mrs? [This was the case brought by Elizabeth Bracewell the widow of William Metcalfe Bracewell, Billycocks eldest son, which bankrupted the partnership and left no money for the other descendants]

R - Mrs Wilkinson at Nelson. Now the Wilkinsons were coloured manufacturers in Nelson, they were in a big way and they had been right up to the do when all manufacturing had gone out. They've always been a big, strong firm and Mary Wilkinson was very good to Ada, they called her Ada. She'd have had to go to the poorhouse, the workhouse if this lady hadn't have taken her on because of course, she'd lived in a big style under her father, Billycock and of course, all at once she's nothing. That's what they used to do. Have you ever read Dickens's 'Hard Times' ?

Yes

R-Well that's what they did in 'Hard Times', you know, threw it into chancery and nobody could get it.

That's one of the cases that I've got to go and have a look at but I've seen some of the papers and there's Smith Smith and Threlfall from Colne who were two of the executors who were these, Christopher Bracewell versus the Executors. Of course it was his younger son C G Bracewell, Christopher George Bracewell was still alive wasn't he when Billycock died, he lived for a little bit longer than his father. Wasn't he living at Bank House at Coates?

R Bank House, yes, that's right. That went to the Slaters. [James was living there at the time the dinner picture was taken] That went to the Salterforth Slaters, James Slater but they all stemmed from Dick Carr. James Slater and John Slater and Harry Slater. I was very friendly with Harry, he went blind and he lived at Morecambe at the finish and he had a boat just the other side of Coates, on the canal and we used to sail on a Sunday and it's surprising when you're in a boat on the canal how wide it seems. Of course there weren't all these cruisers that there are on now. We used to sail to Bank Newton till we got to the locks there again and then get out and walk to the 'Anchor' at Gargrave and have our tea, our Sunday tea and then go back.

Can I ask you something else which is way before your time but you might have heard somebody talking about it. It's to do with William Bracewell. Can I tell you what I've found out and see if you'll argue with any of it. I've been puzzled from time to time, I’ve got very confused about Bracewells in Barnoldswick round about 1845 before they actually built the first mill. I was lucky enough the other day to come across a, reference that helped me out a bit and from what I can make out was this that Billycock's father, Christopher, was living at 'Green End Farm', Earby. He was born at 'Green End' was Billycock. Now Old Christopher, he was a manufacturer in Earby and owned a lot of land. Even in those days round about 1835 and when we say a manufacturer in those days.

(400)

What we're actually talking about is somebody who was - he was putting out to people who were weaving in their own houses. Spinning by water power and putting that yarn out to people who are weaving in their own cottages. He had a putting out shop in Barnoldswick which was - I only found out where it was the other day by a series of coincidences- I found out, at least where I think it was. It was two doors up from the 'Cross Keys'. It's a little cottage that's been built there with two big windows in it, now two big shop windows. It's twenty two and twenty four Church Street. You're looking at me?

The two cottages used by Bracewell.

R - well, it's a bit before my time

It is, yes. I'm not asking, I'm telling you what I think is right. You know, what I think I've found out but then it leads into Billycock and there's something I want you to answer for me, you might know something about. Now, in 1835, Billycock first came into Barlick to act as a sort of manager for his father at his putting out shop in Church Street. In 1846 he’d got to the stage where he started building Butts Mill in Barlick.

R - Aye, Butts was his because we moved from Clough to Butts and we moved from Butts to Calf Hall.

(45 Min)

Ah! I shall be asking you about that. That was the first mill that he built in the town was Butts in 1846. The thing that's always puzzled me is I’ve found references to a William Bracewell in the town before then and it wasn't until not so long ago that I realised that there was more than one family of Bracewells. There was a mill called 'Coates Mill'. I call it 'Old Coates Mill'.

R - It was 'Old Coates'. That's what my grandfather rented off then, you see. He had his few looms; he had only about twenty looms.

That was a water mill, it wasn't the mill that we call Coates Mill now. There was a mill called 'Old Coates Mill' and you know as you go down the side of Crow Nest and Rolls Royce. The car park at the bottom there on the right hand side, there was a water mill there. It was demolished in about 1890 and the last thing it was used for, the Catholics used it to meet there. It was pulled down in about 1890. The fellow who owned that mill was called Nuttall and there was a William Bracewell, well there were two Bracewell brothers. William and I think it was Thomas.

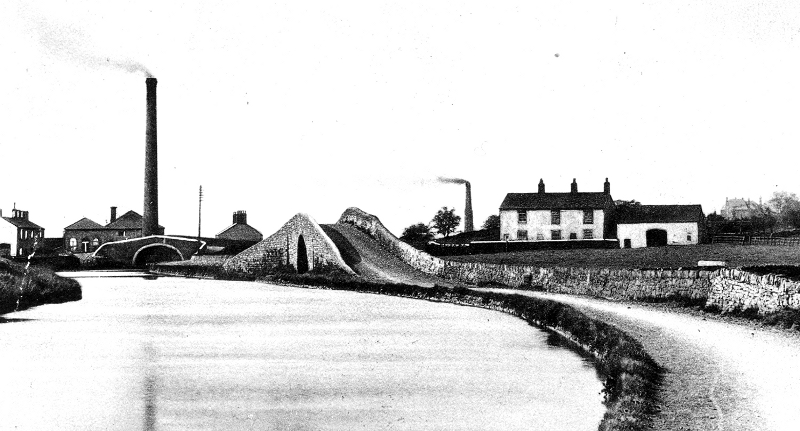

Old Coates mill in 1890 just before it was demolished.

R - The one at Thornton was Henry.

It might have been William and Henry [no], I haven't got those cards with me. They were weaving in there or rather they might have been weaving but they were spinning in there. [When Bracewell Brothers sold the mill they only sold spinning machinery, no looms. This would fit in with small manufacturers working there on their own looms. When they moved they would take them with them.] Now it seems to me that what happened at that time was that Billycock decided he was going to stop them and he started manipulating the water that was going down to them.

R – Oh, now then, you've got onto a right do for Nutters. Nutters at Bancroft, they turned off Joe Slater's water every night and it came down from Springs, you see.

Now when you say Nutters at Bancroft?

R - Nutters at Bancroft, Alfred, Herbert and all that lot. They were right Devils. They wanted the water from this spring at Weets, came down from Weets. They wanted this water for their mill. He hadn't the town's water, had Joe Slater.

When are we talking about?

R ~ Oh, we're talking about when Bancroft was built. Joe Slater lived at Newfield Edge and his water, he hadn't the towns water, it came down from Weets from this spring.

Was it from Springs Dam? It would be because Billycock built that dam and he built the house.

R- Yes, it came from there. That's right. Dewhursts lived at Springs.

(450)

It came to him and it wasn't for anybody else, well they wanted it did Nutters for Bancroft Mills you see, this water. So they asked Joe if they could have it and he said no they couldn't so every night they turned his water off. They were Devils, I'll tell you! They were up to all sorts of tricks, especially Herbert. Do you know, when he went away to the Isle of Man for his holidays, they got his garden seat and sent it to him carriage forward. Oh the tricks they played! I tell you, they were worse than any Chicago gangsters. When they saw me brother, Fred or any of the Nutters coming every lad in town hid. They all flew into their houses. [Audrey says that Fred Nutter worked for Pickles’ as a cloth salesman.]

You're getting forward on me a bit because I'm still back in the middle of the nineteenth century..

R - Ah, well we'll have to come to this again

We'll come to it, don't worry. It's only just dawned on me recently that there was more than one lot of Bracewells. These other Bracewells farmed at Calf Hall and they farmed at Coates as well. In fact the two brothers, one farmed at Calf Hall and the other at Coates. I came across this reference where these two brothers had got the contract for collecting the towns night soil in about 1860 and I thought this is funny. This can't be William Bracewell from Newfield Edge. It was these other Bracewell brothers.

(50 min)

R - Yes, but I think they all came from the same stem. [Stephen was right, they all went back to Christopher Bracewell of Green End at Earby. As near as I can make out, Billycock was cousin to the Bracewell Brothers of Coates]

Probably.

R - But you see it's before my time, that. My father never talked so much about the Bracewells.

What I was wondering was, you've got this water mill down there, Old Coates Mill and I think that William Bracewell, Billycock Bracewell, was manipulating the water that was going down to it. There was a big fight between William Bracewell, I say a fight, it was a court case between William Bracewell and Nuttall’s over this water.[Nuttall had bought Old Coates when Bracewell brothers gave up.] I don't understand it yet because I've got to find out where the case was and go and look at the papers but there was some problem with that water connected with what they called the 'Bowker Drain'. Which runs from that car park there from where the mill was and runs right the way back almost to Park Bridge at Salterforth. Of course it's that drain that kept the lodges going at Wellhouse and I've wondered if you ever heard anybody talking about the Bowker Drain and about the big court cases there were over it.

R - No, I don't know anything about that, I don't know a thing about it. The only court case I know of is Henry Bracewell throwing Billycock's will into chancery. [Elizabeth actually] That's all I know.

Of course it's long before your time.

R - His daughter, Mrs Joe Slater was penniless. The mills get their water from the canals. You see that's why they're all built along the canals.

Aye, some of 'em do.

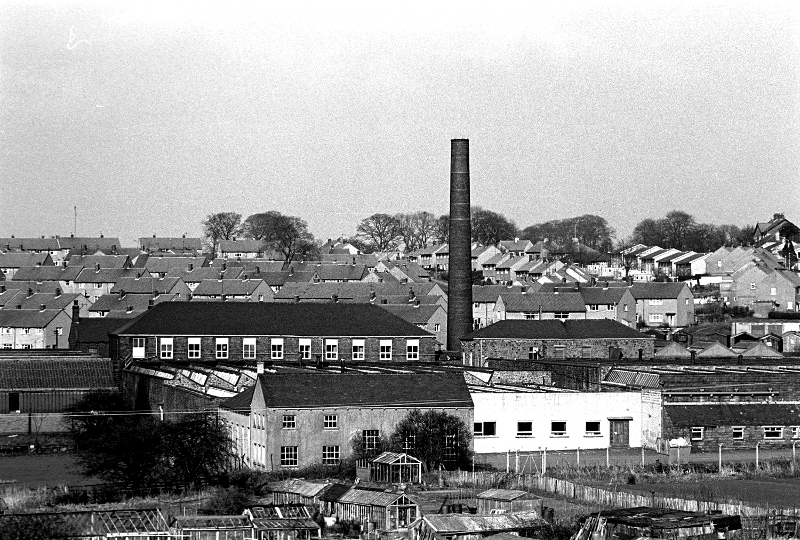

Long Ing Shed in 1985.

Barnsey shed on the left and Long Ing shed on the far right. This would be post WW2 but before the old canal bridge was replaced.

R- Barnsey, our mill was at the side of the canal. Barnsey at one side and Long Ing, [Moss actually] Silentnight - that used to be Widdup’s Mill, before Silentnight had it. Right away into Skipton and all right from Saltaire.

One of the interesting things about that is that Bankfield is next to the canal and doesn't take any water out of the canal. Their lodges are above the level of the beck.

R - Well, Long Ing didn't get any water from the canal. Their lodge there and they were very warm in these lodges and they used to breed goldfish in these lodges that when they changed over from steam to electricity the lodges weren't warm any more, so the fish all died. I stocked my pond, rose garden pond at Foulridge [Woodlands], I stocked it with goldfish from the lodges. Wellhouse was the best place.

(500

Ted Fishwick, who worked for us, he came one morning and he rang the bell and he says, we always got up at quarter to seven the wife and me, and wife's downstairs and Ted says, "Hello Mrs Pickles, I've brought you some fish". She thought it would be trout, you see. So she says, “Wait a minute, I’ll go and get a dish." He said, “They’re goldfish for your pond." He'd got 'em out of Wellhouse lodge.

That Bowker drain, it's something I've got to find more about. There's one thing sure and certain as far as I can see the main reason it was put in was to catch the leakage from the canal and it goes right underneath Long Ing Shed.

R - There was a leakage under the canal, you know and there was 'Little Cut' as they called it.

Rainhall.

R - Well, yes. We reclaimed the land over that. There's always been a leakage there because they were always working on it, were the canal company. [After the Little Cut to Rainhall Rock quarry became redundant, Pickles bought the land next to Barnsey and filled the old canal in.]

The canal at Long Ing before Barnsey and Moss were built. Long Ing Shed is in the centre and the bridge over the entrance to the Little Cut is on the right hand bank.

(55 Min)

They've sheet-piled all the side.

R - Finding where it was going to and they couldn't, they never did.

Let me tell you something, we're going to finish in a minute because we've done enough for this afternoon. I’ll tell you something very strange about that, it's funny what I dig up. I keep getting word about the Bowker Drain and I’ll tell you who knows all about the Bowker Drain and he's a great friend of mine and he tells me all sorts but every time I start asking him about the Bowker Drain he clams up. Harold Duxbury, Harold knows.

R - Oh, Harold! Harold, he did the work on our farm at Thornton and all that. He kept it as a backset, you see if there was anything going on at Dower House at Gisburn for Hindleys and that. He didn't bother with those and he was charging us the earth and a friend he says, “There's yon Duxbury there playing away with the Salvation Army on a Sunday and during the week he's doing us all the week.”

The reason Harold knows so much about the Bowker Drain is Duxbury’s re-piped the Bowker Brain because, for a start off as Calf Hall Shed Co., Harold was on the committee at the Calf Hall Shed Co. and the Calf Hall Shed Co. were interested in it because it was the Bowker Drain water that kept Wellhouse going.

R - The men on the – [Edmondson] Banks on the Shed Company. We rented Calf Hall from them and Butts, they had them both.

Brooks Banks and Edmondson Banks.

R - There was one lived half way up Weets, one of the Banks brothers. He had ducks and that in his garden. I know his father and I walked up to it many a time. Henry Banks. [Springs Farm]

Henry?

R- Aye, there was Edmondson Banks, Brooks Banks and Henry Banks and they were all in Calf Hall Shed Company and they acquired Butts from Billycock's executors and so they had both mills that we were in, you see. Well, when we had the flood in 1930.

Thirty two.

R-Aye, thirty two.

(550)

Twelfth of July.

R - Snowdon was Chancellor of the Exchequer. Our looms at Calf Hall were under water. At Butts we had a cellar. It was a good place for keeping yarn and we didn't buy yarn to cover sales, we just bought yarn when we thought it was cheap. Father was very clever about knowing about that. We had it full of our yarn and it came [flooded] and do you know we used to sell it to John Watts at Burnley and they wouldn't touch it. They wouldn’t touch our cops. Albert Hargreaves, we got him to come over.

When you say you sold it to John Watts, do you mean waste?

R-Aye, waste but they wouldn't touch this mildewed yarn. So Albert Hargreaves came over and me father, he spent hours and days sorting this out and what was any good at all, you see. Now all these cops, he went through every blooming skip and he worked a week on it and Albert came and he says, “I can only give you 1 ½ d a pound, Mr Pickles. My father said, “Well, I don't want you to lose any money on it, Albert” Then after he'd got it to his place at Padiham, he came and he says, “I’m sorry Mr Pickles,'” he says, “I can't make a do at 11/2 d. My father says “Well, what can you do?” He said “I can't give you more than ¾ d” My father said, “Well, ¾ d it has to be then because I don't want you to lose any money on it.” He bought it all for ¾ d and of course he got all of our business after that, did Albert. We never did any more with Watts. Clock Tower Mill, you can see it as you're going out of Burnley towards Rosegrove there.

That's it.

R - We'd always done our business there with Watts but after that we did it all with Albert.

That drain, that Bowker Drain that ran Wellhouse. That drain now supplies Rolls Royce at Bankfield with what they call the foul water supply, which runs all the washbasins in the works, all the lavatories, boiler feed, swilling down, condenser water for the air conditioning. I was talking to a fellow who works for Rolls and he said, “Oh, I know a bit about the Bowker Drain but not much.” He said, “We had to do a test on it one day to see what it was running and we had a pump that was doing 800 gallons a minute and it wouldn't hold it back.”

(1 hour)

He said “We couldn't lower the level in the well.” Anyway he never said anything to me but three days afterwards, there was a big envelope plopped in through me window. Nothing written on it or anything and I opened it up and it's a set of copies of the Rolls Royce drawings of the Bowker brain. This fellow swears he doesn't know where they came from. It's a set of drawings of the Bowker Drain and do you know, that place just near Cockshott Bridge where the Canal Company are always looking for a leak. Do you know why the canal leaks there? Because somebody has put two big baulks of timber underneath the canal and they've gone rotten, twelve inch square. Do you know, I don't know enough about it yet but I reckon they were put in there when they were building the canal and I reckon that someone's put them in. Someone has been very very clever and they knew that when they went rotten the canal would start leaking. Only last Summer I was watching the workmen down there. I didn't say anything to them but I watched them and they were digging there and they had this big pump in but there was all this water bubbling up and they couldn't stop it. [Much later I realised that it was not as devious as this. The 12” baulks I had seen on the map were drains to de-water the land on the other side of the canal as its natural course had been blocked by the construction.].

(600)

I was talking to a man, I do an evening class in Barnoldswick, I was talking to a man whose father, and I’ve forgotten his name. His father used to be one of the directors of the Calf Hall Shed Co. We were talking about the Bowker Drain in this history class.

R - Rushworth?

No, not Rushworths, no.

R - Rushworths were also in - oh no, Rushworths were in Long Ing.

Yes, but we'll get on to Rushworths later, George and ... There's plenty about George and them. This fellow, I've forgotten his name. It doesn't matter anyway I was talking about the Bowker Drain and I was talking about CHSC owning Wellhouse and it being a great thing for them. He said, “Do you know Stanley, that’s explained something to me that I’ve puzzled over for years. When I were a lad, me and me dad were walking along the canal bank there. As we were passing a well, you know stone well down in't side of the bank like. Me dad turned round to me. There were a funny little grin on his face. He turned round and said, ‘I’ll tell thee what it is lad, if ever tha wants any watter for nowt, take it out of theer’ and he smiled. And he said I'm going to go back and have a look. From what you've told me, it sounds as if it's on't line of the Bowker Drain". “That’s what it would be” I said, “He was giving you a bit of good advice.” The Bowker brain is still being used to supply water to Rolls Royce and every drop of water that comes down the Bowker Drain, all right it's not a fiddle, but it's certainly coming out of the canal.

R - Barnsey belonged to about oh 60 or 70 folks.

Barnsey Shed?

R - Aye. They were every bit of a grocer. Yates's grocers.

Sam Yates?

R - Aye, Sam Yates. Tinner we called him.

Harry Tinner.

R- Mother used to send her daughter, my sister you know, Lena. She says, go down to Harry Tinner's and get a piggin. Do you know what a piggin is?

It's like a dipper isn't it?

R - A lading can, aye.

What was his proper name, Harry Tinner? What was his proper surname?

R - Hargreaves wasn't it?

I don't know, I'm asking you.

R - Yes, Hargreaves. She went into the shop and said, “My mother wants a piggin, Mrs Tinner” She was quite mad at being called that. She was like that, me mother.

(1 hr 5 min)

There was Edmondson’s had a grocers shop so my mother said, “Oh we've no bacon for tomorrow. Go down to Edmondson’s and get pound of bacon - and I want it fat bacon cut thin as sharp as grease lightning.” So my sister went into the shop and said, “Mrs Edmondson, my mother wants a pound of fat bacon cut thin and as sharp as greased lightning!” Well that was for her, you see, to be as sharp as grease lightning, not Mrs Edmondson.

So when they built Barnsey, was it a Shed Company? Did they call themselves the "Barnsey Shed Company?

(650)

R - Yes, they did and there was Sam Yates and there was… 'Pots, Paints and Pasties', they called it because there was every shop in Barlick had an interest in it. Pot shop, Jowetts had the pot shop. I forget who had paints - oh Petty’s, and pasties were confectioners. When we bought it, Norman Petty was the accountant and he’d about sixty or seventy places to go to a day! Well, they all had a few shares in them. He’d to buy them all out. Some belonged to people as far away as Liverpool!

Would it surprise you to know that there are things in Barnoldswick, even today that they still haven't found all the shareholders of?

R - You know we had a nickname for everybody in Barlick. We never called anybody by their proper name. One morning, I'll tell you this, mother said, “Stephen, I wish you'd get somebody, this tap's been leaking for three weeks. Will you get somebody to deal with it?” He said, “On me way to the mill I'll call at Oh Dearie and tell him to come up and put it right.

Call at "Oh Dearie’s"?

R - Oh Dearie, yes. So he came up and me mother says, "Oh I am glad you've come Mr. Oh Dearie. I've been asking Stephen for three weeks to get this done, but thanks very much for coming Mr. Oh Dearie. Well, my father said, "Did Oh Dearie come?" “Yes” mother said, “Yes”, but he didn't look so pleased when I called him Mr Oh Dearie!” Well, he says, that isn't his name. He's had that since he was a kid because when he was a kid, because according to the school he kept saying 'Oh Dearie me, I want to pee.” So they called him Oh Dearie for the rest of his life.

And who was that? Which plumber was that?

R -I don't know whether it was Martin or not. Something like that.

Aye, Martin.

R-He lived there at top of Butts there at Calf Hall, that mill [shop] there at top of Butts.

I remember Ernie Roberts once telling me about a manager at Widdups, now wait a minute, they called him Cabbage didn't they. I said, “Where did he get that by-name" He said "When he was a lad, his mother wanted him to go to the shop for a cabbage. He said, ‘How big do you want it?' She said, Oh, about as big as thee head.”

R - My father, my brother, Fred they never called anyone except by nickname.

You know, the only place I know of where it’s still going strong, that, is Foulridge.

R - Do you know, there's a lot of words, we made them up ourselves.

(1 hour 10 min)

They'll die when I die because there's nobody to carry them on. You see, we used to say, “He’s been treating us with marked conspermacy. Well, there isn't such a word as conspermacy in the dictionary you know, because we made it up. That it is, it should be contumely, you see. All sorts of words.

(700)

When we used to walk up, I've been an honorary member of the 'Reform Club' at Manchester now for about ... what? 15 years and we used to walk up from.. Now my brother never said anything to anybody. If he didn't, he hadn't anything to say. He didn't say “What a grand day it's been” and all that sort of stuff. So we're walking up from - there's four of us and we used to go up to the top of King Street. Well our offices were in Spring Gardens and we came to the top of King Street where the Reform Club was and then they used to say, Jamie Tattersall and his assistant from Nelson and me and me brother, and me brother used to say, “Well, it pog din og” That meant half past twelve, dining room. Jamie used to say, my brother was teetotal and Tom Parker was teetotal but Jamie says to me-"Tha mun come in at quarter past twelve and then we can have some treacle before these teetotallers come in!” They called their drink treacle.

Anyway, we're walking up from Salford Station and I says, "We're on our own today Fred” So he never spoke. We got to the top of King Street and he said, “What did you say?". I said, "we're on our own today." He said, "What do you say?'' I said, "Miss Miller (that's the girl) she's off with 'flu. That's genuine." I said. Then Fred Nutter's off. He's nowt wrong wi’ him but he's off in bed with it.” He’d stop off if he’d a bit of backache or a bit of a tickle in his throat would Fred Nutter. So I said, “We're on our own” In those days the lorry men came up with cloth from the mill and then the girl used to write out the invoices and that and where they'd to take them to in Manchester. We’d a big telephone like that, nothing like they have today, A B X or something it was called. Although we’d only three offices, we’d enough plugs for the whole building. And so he says to me, “Aren’t there nobody coming?'' I said, "They're not here, they're not here, it's just you and me.” He said, “Well, we could manage if either of us could use that telephone. Neither of us can so we’ll have to write everything out by hand! Silly telephones were those.

SCG/08 December 2002

10367 words