TAPE 78/AI/01

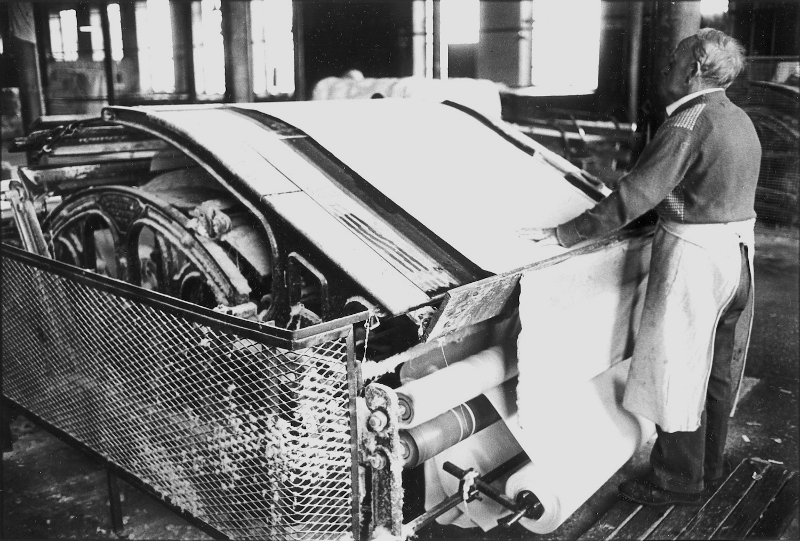

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON SEPTEMBER 21ST 1978 IN THE ENGINE HOUSE AT BANCROFT SHED WHILE THE ENGINE IS RUNNING ON A NORMAL WORKING DAY. THE INFORMANT IS STANLEY GRAHAM WHO IS THE ENGINEER AT THE MILL.

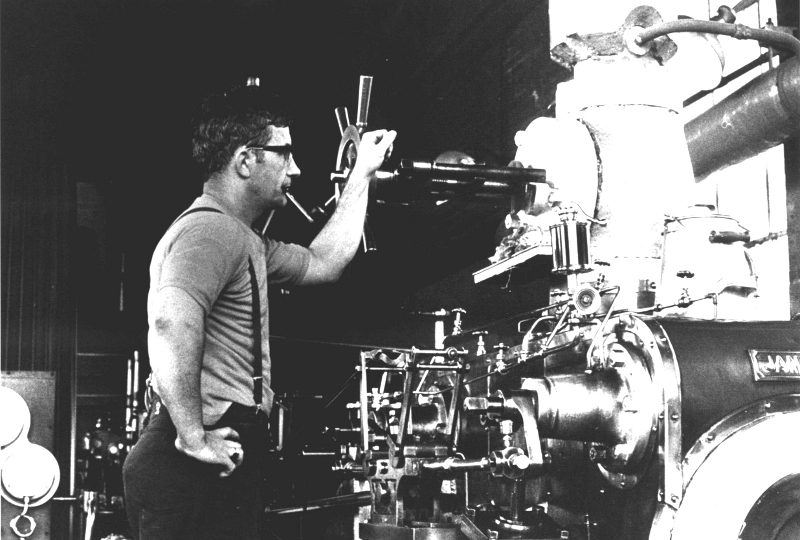

Stanley in 1976 ready for stopping time at Bancroft.

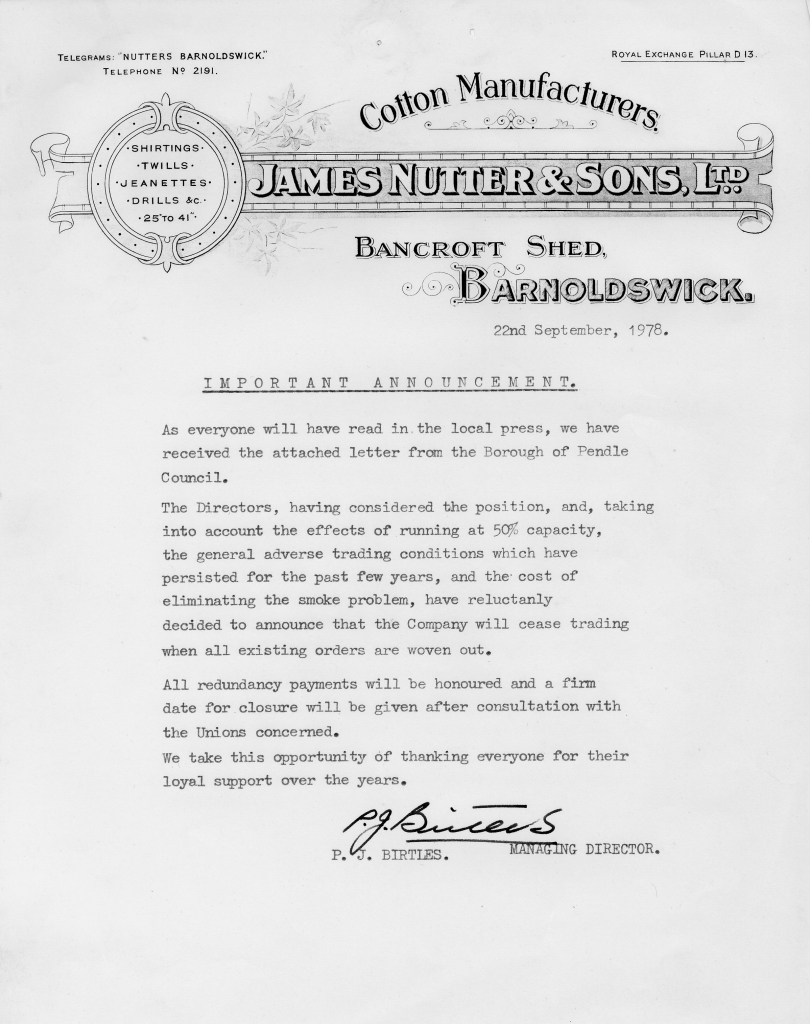

Now the reason why I am making this tape today, here, is that today is Thursday 21st of September. On Tuesday 19th September we finally got the word that we have been expecting for a long time now that this mill is going to weave out on December 22nd. In other words, we are all going to be redundant, out of a job. This is no shock but it’s very sad. I think everybody feels the same way about it. It's a shame, Bancroft is a happy place to work at, and it seems that happy places to work at can’t make money these days.

(50)

What I intend to do this morning ... I should say that it’s seven minutes past eight, we have just started up, the shed light’s in, in other words there is a fair load on the engine, we are running at about 120 pound of steam, there's not much weaving load on because we have only got about 200 looms running, 220 looms running, but the shed light’s putting 100 or 120hp on to the drive and anybody who is an expert on Corliss valves will be able to tell by the noise in the background that the valves are running on about 50% cut off. The engine's probably turning out about 300-350 hp at the moment. Now, as I say, the reason for making this tape this morning is because everything’s fresh on our mind about redundancy and from now on the load will go down on the engine and the plant and if we don’t do a recording of some of the sounds in the mill now I’m afraid we won't get them because these things'll catch up on us faster than we think.

I should just explain one or two things about the actual mechanics of weaving a shed out. It has to be understood that weaving like any other

(l00)

manufacturing process is as it were a pipeline, raw materials are going in at one end and finished cloth coming out at the other. When I say finished cloth, grey cloth in our case, which in the terms of the trade is unfinished cloth, but we are actually manufacturing cloth. Now obviously we have to contract for our raw materials and people also contract with us to supply then with cloth so it isn't possible to just shut the doors and go home and say ‘That’s it, Bancroft's finished.’ We have to honour our yarn contracts, and we have to honour our cloth contracts as well. So in effect what this means is that Bancroft will now - as we say in the trade - start to weave out. In other words, as cloth contracts finish, as orders are fulfilled, machine’s will be shut down and they won't start up again. As the number of looms drop, so the number of weavers will drop. We still have some sets to tape but as soon as those sets have been taped, obviously the taper will go. So we are now entering a period of rapid decline which will last about three months and we shall weave out on or about 22nd of December. It may be

(150)

a day or two earlier. Who knows, we might have a little more to do, I don't know but it will be something like that. We shall finish up, the mill will in effect be run by three or four men, the last tackler and possibly one weaver will be weaving out. Jim the manager will still be here because he has got his twelve week notice and of course I shall still be here to provide motive power. I shall make sure the fire beater's also here as well. I can see the situation arising where the management will say that due to the decreased load, we don’t need a fire beater. Well in actual fact this is wrong, because as the load decreases on the engine it becomes more difficult to run In many ways the easiest engine to run is a fairly heavily loaded engine because you have no problem about suddenly fluctuating load as there is plenty of capacity and plenty of power going out. But on very small loads you only need somebody to shut down one small thing and you could probably lose 25% of your load, which can mean your governor flying out. When I say the governor flying out, it moves in such a violent way that the safety gear overrides everything and shuts the steam off to the engine and stops it. However, I shall surmount these difficulties by

(200)

running the engine at a lower pressure as we go on. Obviously there is a point where you reach a pressure, there in not much point running actually at below 80psi. pressure because you start to burn more coal. But what we’ll do is just go for a little walk and listen to some of the sounds of a Lancashire mill running. Now, unfortunately we can’t record the tapes because they aren't running. It's possible that they will run at some future date but in actual fact the noise that the tapes make is not very striking, it’s only a rumble of gears and an occasional click. The striking things really are the sound of the stokers on the boiler, obviously the sound you can hear in the background is the engine, and the weaving shed itself. A Lancashire loom is a very noisy thing. A lot of firms have spent a lot of money trying to quieten them down. Some of the modern looms are even more noisy, it's impossible to work in some weaving sheds without ear defenders, in other words ear pads or muffs or ear plugs to physically stop the sound getting into your ears. I have a friend who inadvertently went into one of these sheds and spent about two hours in there one morning and finished up it made him physically sick. Lancashire looms don’t have that

(250)

effect an you but they do make a lot of noise and it is a very striking place when you first go in. In point of fact nobody wears ear defenders in a Lancashire weaving shed, it isn't bad enough for that but it should be said at the same time that most weavers finish up with some impairment to their hearing after five, ten, fifteen, twenty years in the shed. Now

(10 min)

Bancroft Shed was built originally to take over 1000 looms. This was what was referred to when it was built, as a 1000 loom shop. This was reckoned to be a nice sized unit, a good, profitable size unit. There is actually room in the shed for about l,150 looms. At the moment in that shed there'll be about 450 to 500 and of these only just over 200 are running so the noise is nowhere near what it would have been in the old days when all the looms were running at the same time. There is one advantage to this, it will mean that we can walk up under the shaft and listen to the shafting itself, the line shaft, the main shaft which goes from the second motion pulley right the way up the mill, 300 feet up the mill and everything else is driven off it. And we'll be able to walk up that and, due to the fact that there are no looms at that side of the shed we'll be able to listen to the noise of the power going up the shaft. Actually, the noise is caused by the

(300)

fact that the gearing is cast iron and is not as accurate as it would be made nowadays under ideal conditions. A good gear running under ideal conditions is virtually silent. Our gears shout their purpose out to the world. They, nobody can describe them as silent. It's worth mentioning here that in the old days this wasn’t seen as any great disadvantage and you would often hear an engineer say "Oh they'll be all right, leave them alone. They'll sort it out between themselves in the finish.” In other words they’d wear into each other. One interesting point about the gears, for anybody who is listening to this tape who is technically minded, they have a hunting tooth in, in other words they are not, they don't have the same number of teeth in. This means that the teeth aren’t mating with exactly the same tooth every revolution. If you had two big gears and they each had 100 teeth in, the same teeth would mate with the same teeth each time and you get a lot of localised wear. If you put a hunting tooth in one, in other words put 101 teeth in one gear and 100 in the other, or 99 in one and 100 in the other, this is called putting a hunting tooth in. It's easy to see, if you just think about it that the teeth would be moving round and meeting a different tooth each time. This evens out wear, localized wear and eventually you do get a quieter running gear. But I’m afraid the theory doesn’t always work, there was a famous pair of bevels in Earby that, well you could hear them from one end of the main street in Earby to the other for years at Victoria Shed, and they never did quieten themselves down until the mill was finished. Anyway that’s enough about gearing, what we'll do first is have a quiet walk down and listen to the stokers running in the boiler house.

(350)

The boiler front and stoking floor.

Well we're outside now, in the boiler house yard. I don’t know whether you can hear the birds singing but it’s a grand morning, blue skies, just a little bit of smoke coming out of the chimney but not much and in a second or two I shall just walk across to the boiler house# and we'll listen to the sound of the stokers running away. The boiler at Bancroft Shed is a single Lancashire boiler, it’s 30 ft x 9 ft - which is a big boiler by anybody’s standards- and is fired by coal. Now, in the old days, when they put a boiler in, when I say in the old days - up to probably about 1880, boilers were all hand fired, what we call handball, banjo work. The fire beater just kept shovelling coal in as and when it was needed in order to keep the steam up. This is one of the reasons why in the old days there was so much smoke from factory chimneys, because in order to shovel coal into the fire it was necessary to open the firebox door obviously. And when you open the firebox door, you allow a lot of cold air to get into the fire which upsets the combustion conditions, in other words hand firing of a boiler automatically leads to imperfect combustion. If you have got a fire that’s running just right with just the right amount of air going in both beneath the bars and over the bars to burn smokeless - the noise you can just hear

(15 min) (400)

in the background probably is the auger that's putting coal up to the stokers. If you have just got the exact amount of air going in to the firebox to burn smokeless, in other words to burn efficiently because that’s what smokeless burning is, it's efficient burning, it's obvious if you open the [firebox] door you are going to upset all those conditions and you have got to get smoke. In fact as we are running now with the stokers, if we were to allow excess air to go over the top of the fire we would get smoke straight away. In point of fact that is one of our difficulties. Over the last few months Barnoldswick has become a smokeless area. Now in actual fact this made no difference to us in certain respects as industry has been running smokeless, or has been governed by rules about producing smoke, for a matter of, I’m not sure what the exact date is, but a matter of 20 or 25 years and domestic fires weren’t covered by these regulations. In other words we could be prosecuted for making black smoke whereas nobody with a domestic fire could be prosecuted for making smoke out of their house chimney. Now a few months ago Barnoldswick, or our area of Barnoldswick was made into a smokeless zone. Now this meant that the domestic fires weren’t allow to make smoke. Now nobody had really bothered about the odd bit of smoke coming out of Bancroft chimney before but as soon as the domestic fires were stopped from making smoke people began to ask questions why was Bancroft allowed to make smoke when nobody else could. Now, these stokers that we have on - the proper name for them is the Proctor wide ram unit coking stoker - now they are, in point of fact a very good stoker, they are fairly reliable, a bit heavy on spares but they are not a bad stoker at all

(450)

as long as you have got a fairly heavy load on. In other words, the efficiency of the stoker depends on the length of the fire in the firebox. Now our fire bare here are 6 ft internally, in other words the firebed itself in each tube of the boiler in 6 ft long by about 3 ft wide. Now under the conditions that we run under now - obviously with only 200 looms instead of 1000 looms and one tape instead of three tapes and less electrical load we don’t need to fire as heavy as they used to do in the old days. Now again it's obvious if you think about it, this boiler was big enough to carry the load of the shed when it was running as a 1000 loom shop so now it's severely under loaded. In other words the fires are running very light. Now with this type of stoker which has walking bars in which the bars move in such a way that they quietly move the fire down the box away from the stoker, the coal’s burning as it goes - until eventually it drops over the end of the bars into the ashpit as totally burnt clinker and ash. The efficiency of your fire depends on having your bars full right to the back of fire. In other words the coal wants complete combustion, in other words turn into clinker and ash, nothing but clinker and ash just as it reaches the back of the fire bars otherwise you get a dead patch at the back of the bars, which is thin and allows excess air through. So that what you are doing is allowing excess air into your combustion chamber, which spoils combustion condition, and it is in point of

(20 min)

fact almost impossible to run Proctor coking stokers on a light load, that is a short fire and run them smokeless. Now this is our trouble, we have realized this for a long time and well 18 months ago I pointed out to the

(500)

management that great savings could be made by altering the method of firing. Now, the easy way to do it would have been to go over from the wide ram unit coking stoker to underfired stokers. Now the underfired stoker is a different principle altogether, it is a firebrick pot inside the combustion chamber completely sealed off from the outside, and coal is forced up a tube by an auger into the pot where it is ignited by burning coal which is already there and the correct amount of air for the amount of coal that you are putting through is blown up into this pot as well. So in other words you can put the exact amount of air that you want with the exact amount of coal that you want in order to promote ideal combustion conditions in that furnace. Which means, in effect that you could run, at any level of load, smokeless. Which also means that you can run more efficiently, save coal and in point of fact if we’d fitted these underfired stokers we could have shown a saving of probably about 10%. It's worth noting that the government is aware of this sort of thing and there is at present a scheme whereby if you can show that an improvement you intend to make to your plant is going to show a saving of 10% or more on energy cost the government will give you a 25% grant towards it, and I'm sure that we could have qualified for this grant. The cost of putting these stokers in would have been, at this time about £8000, that included the stokers, the necessary brickwork and necessary electrical work. We could have put them in complete for about £8000. At the time when I put this suggestion up I was told that we hadn’t any money. Anyway early on this year, I first put this up in about 1977. Earlier this year I pointed out to them that we did have the money because we had 200 tons of coal in stock up the yard which at about £35 a ton, which is about £7000 and I pointed out to them that if we

(550)

burned the stock it would put the coal account £7000 in credit which, together with any grants or anything that we could get hold of would enable us to put these stokers in, actually for no money at all. And in point of fact if we had put them in and ordered the same amount of coal for the next year, 12 months later we would have, when I say ordered the same amount of coal, ordered the same amount that we would with the Proctor stokers. We’d finish up with brand new stokers, and our 200 ton of coal in stock again up the yard. Because we are burning about 1000 tons a year, and our savings would have been at the very least, 10%, and there you are, we could have had the stokers for nothing. But that's all water under the bridge now and we are running out for the last three months on the old Proctor Stokers, we are still making just a little trace of smoke, but I have no doubt that the smoke people will leave us alone now. And even people like that don't kick a dog when it's down, and we are certainly down. Now, we'll just walk across now into the boiler house itself. In the old days the stokers would be driven by pulleys from the shafting, in fact the shafting is still in but nowadays we run them with electric motors (sound of the stokers running). [I probably mention this again later (it's 35 years since I made this tape!) but when I ponted out that we had £7,000 sat in the yard it was news to the management and they told me to burn the stock and it became obvious that they were just realising the asset. As I told John Plummer, my firebeater, I was the biggest fool in Barlick because in effect I had closed the mill!]

(600)(25 min)

That's the sound of the stokers running. The moaning noise you can hear is hydraulic gear boxes which are driven by electric motors which move the ram which forces the coal in and the bars which go backwards and forwards. The hissing noise in the background is under fire steam which is a small quantity of steam blown through pipes under the fire bars, not as some people think to improve the draught or cool the fire bars, but simply to promote a chemical effect in the bed of burning coal which means that the clinker won't stick to the bars. It also improves the combustion of the coal. Water on coke, which is in effect what it is in there of course, produces water gas which is in itself flammable. It's a debatable point whether we should be blowing steam underneath, I’ve often thought that it's a very inefficient way of doing it, it seems to me that atomised water could do just as well. And if you work out what the steam costs you that you are blowing under the bars for a year it's fantastic. It's amazing what this is in a ½ inch pipe. This is cracked right down, but it's amazing what a ¼ inch orifice will use in a year and steam is a very valuable commodity. I don't know whether you can hear a rumbling noise in the background, I'll just walk down the side of the boiler. The boiler is separated from the shed by a 6ft wide passage and a very thick brick wall. This brick wall is the wall on which the brackets are mounted which carry the transmission shaft up the side of the mill. I'm getting down the back of the boiler here now, we are getting away from the noise of the stokers. I'm walking down the side of the economisers now which are a nest of cast iron tubes which stand in the flue at the back of the boiler and the feed water for the boiler is pumped through these tubes which of course pre-heat it and gives us a saving on the boiler. This is exactly the same principle as putting

(650)

hot water in the kettle at home, it boils quicker and you use less power.

The top of the economiser.

I’ll just turn the level up a little bit here and see if you can hear the shaft (sound of lineshaft rumbling). That low rumble is something which you can get used to working in a power driven steam mill like this, it's the sound of the vibrations from the gearing being transmitted through the wall. It's a very comforting sound in many ways because you know that if that gearing's rumbling like that your wage is going on. Of course in about three months that gearing will fall silent and no matter. There is a possibility that the engine might be used for generating electricity, if anybody buys the mill that would be the economic thing to do but one thing is certain, that the shafting will be done away with. So that noise won't be heard any more.

The boiler top.

The boiler house is a dirty place, there’s no getting away from it. It’s no good saying it isn’t because we are burning coal. Coal's dusty dirty stuff. We whitewash once a year for two reasons, one to keep it clean, and the other is that if we whitewash the settings of the boiler, the brickwork round the boiler, it does seal up a lot of little cracks and stop air leaks which again leads to more efficient combustion. We walking back now to the front of the boiler. The firebeater is often regarded as the lowest form of life in the mill next to the loom sweeper because he is generally mucky. He can’t help that but the fact is that without a good firebeater the engineer's lost. The firebeater is the start of the process, he is burning coal to make steam which powers and heats everything in the mill, it’s used for the processes, everything. A bad firebeater can soon waste half a ton of coal a day, he can make everybody else's efforts, economic production, just

(700)

absolutely useless. This fact has never been realised at Bancroft. The firebeater has never been paid a wage which measures up with his responsibilities. It should also be said that he is working with something which is very, very dangerous. A Lancashire boiler is in effect, a tank 9 ft across and 30 ft long with about 6000 gallons of superheated water in it and steam at anything up to160 lbs pressure. A boiler is in effect a big bomb. In the old days they used to say that in a boiler this size running at 140psi there was enough energy to lift the boiler and its contents 7000 ft into the air. Which isn’t a bad way of describing the power that’s locked up in there. You realise this when you blow the boiler off, in other words let the steam off it when you are going to do any maintenance. The noise is fantastic, a 3” pipe blowing steam at 140psi directly into the atmosphere is in many ways a frightening thing. And when you come to consider it takes about 20 minutes to blow off, if you imagine all that energy being released in a matter of a fraction of a second, if the casing of the boiler ever fractured or there was an accident, it gives you some idea of the destruction and damage that can be caused. Anyway, we'll go out of the boiler house now and back into the engine house. The boiler house is of course right next to the engine house. This is deliberate, the shorter the steam pipe to the engine, the better. As a matter of interest at Bancroft Shed we always considered that they were working under difficulties here. For some reason I don’t know what it was, I think that there was perhaps bad bearing ground next to the engine house. Because the boiler house should have been built the opposite way around to what it is. It should have been built so that the back of the boiler was as close to the engine house as possible in order to keep the pipe short, the steam pipe to the engine short. But in fact they built it the other way and there are certain indications in the warehouse and in the bottom of the bunker that there is perhaps some form of spring water coming up or something like that which would have made it dangerous to site a boiler over

(750)

it. Because obviously a boiler on brick settings, you want it on firm ground. And I think they realised this when they built it and that's why the boiler house is built as it is. It’s actually detached from the engine house. The engine house itself is a beautiful building built of dressed stone with rubble face, sawn lintels, big windows down either side and a very big window at the end. In the cellar the engine beds are absolutely solid. Of course they have got to be. I have heard it said that the engine house actually costs more than the engine but in fact this isn't true from our own researches in Barnoldswick. We have found out that this wasn’t actually true. It was amazing how cheaply an engine house could be built. It seems that labour was so cheap in those days and that materials could be bought cheaply because of course that was locally cut and dressed stone. The mortar of which they were built was local lime ground up with ashes from the local mills and everything was obtainable locally and there was plenty of cheap labour and it meant that the actual fabric of the building was one of the cheapest things to put up. The engine of course had to be bought from away and installed, even in those days fairly skilled men and of course that was more expensive. So now we'll have a walk down into the

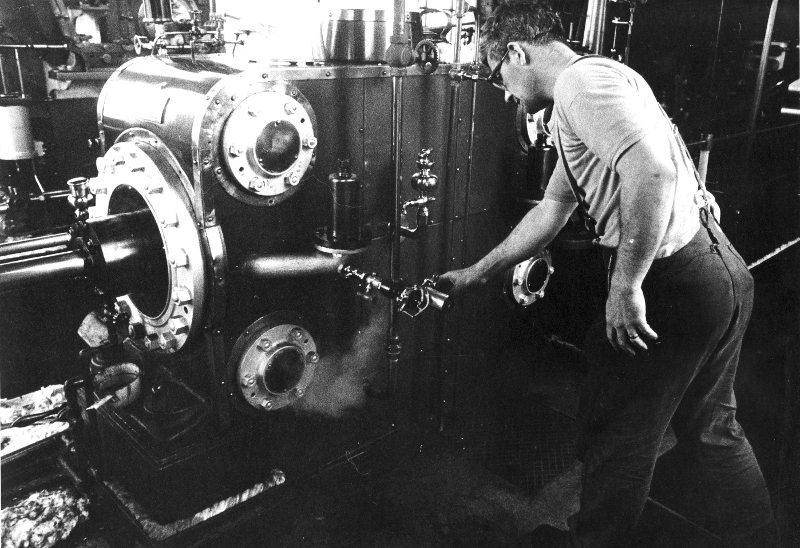

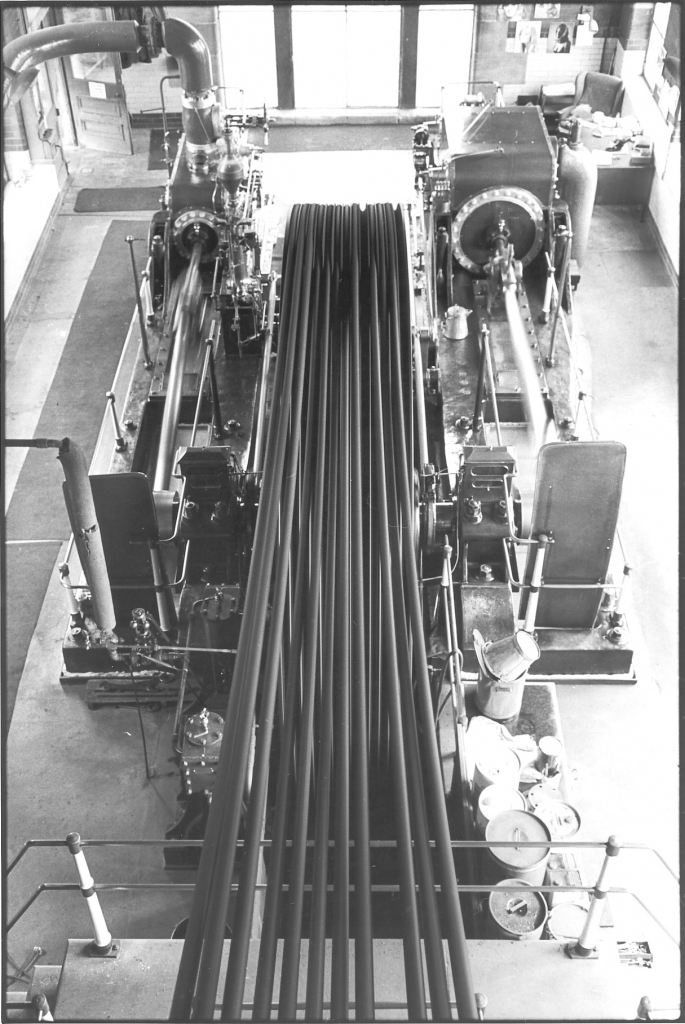

(35 min) (800)

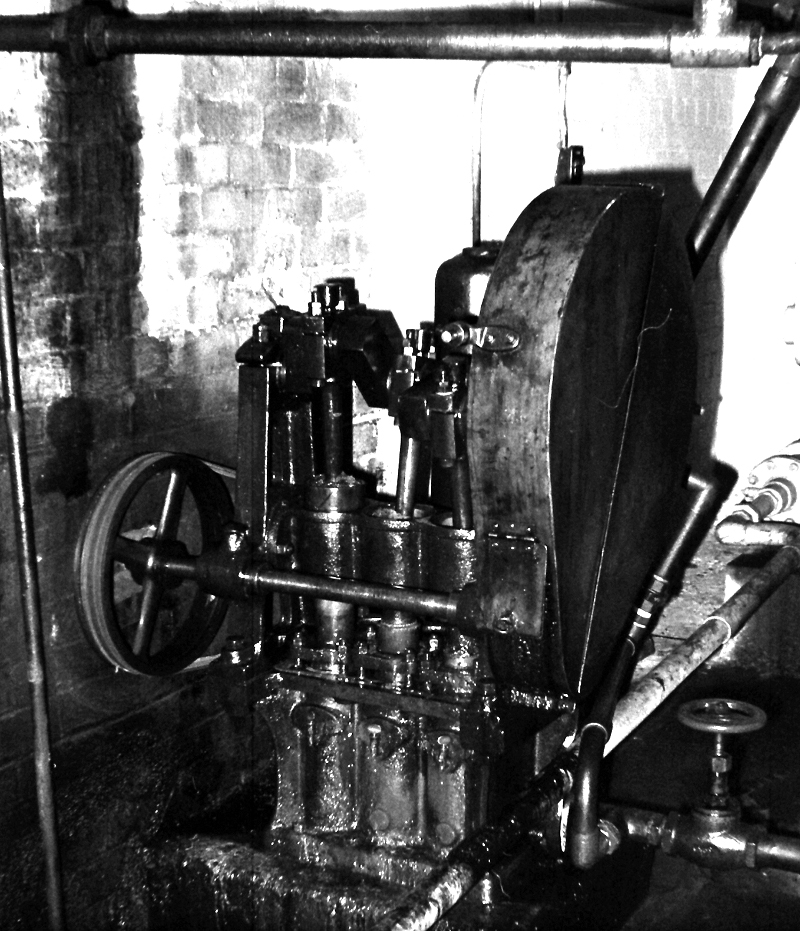

cellar. The cellar is where the pumps live. There are three pumps, the largest sits right in front of you as you come through the cellar door.

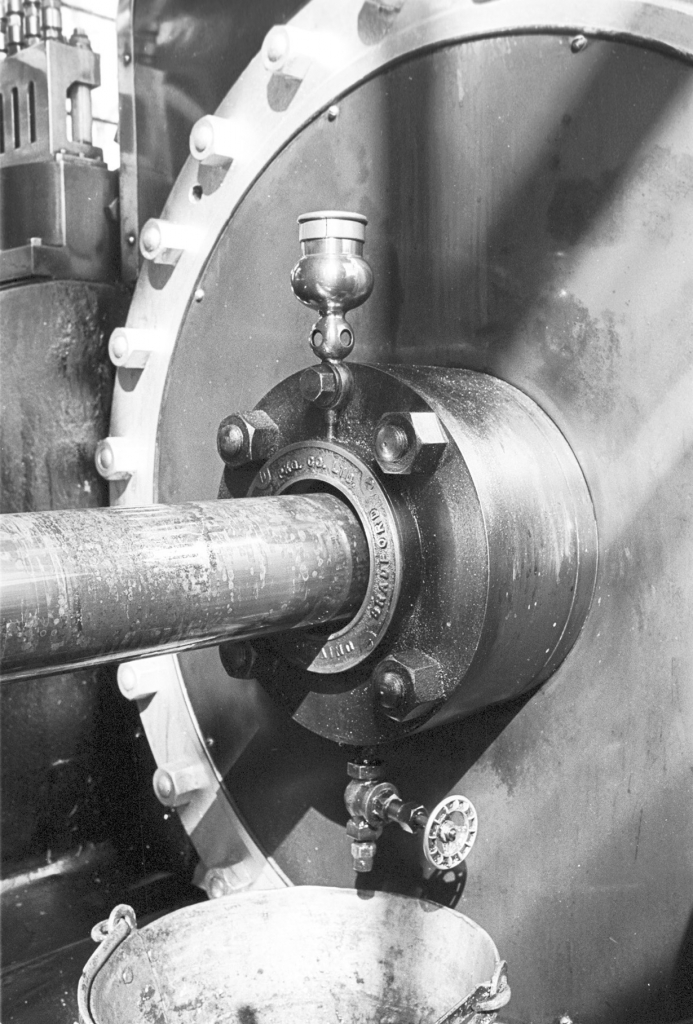

The air pump.

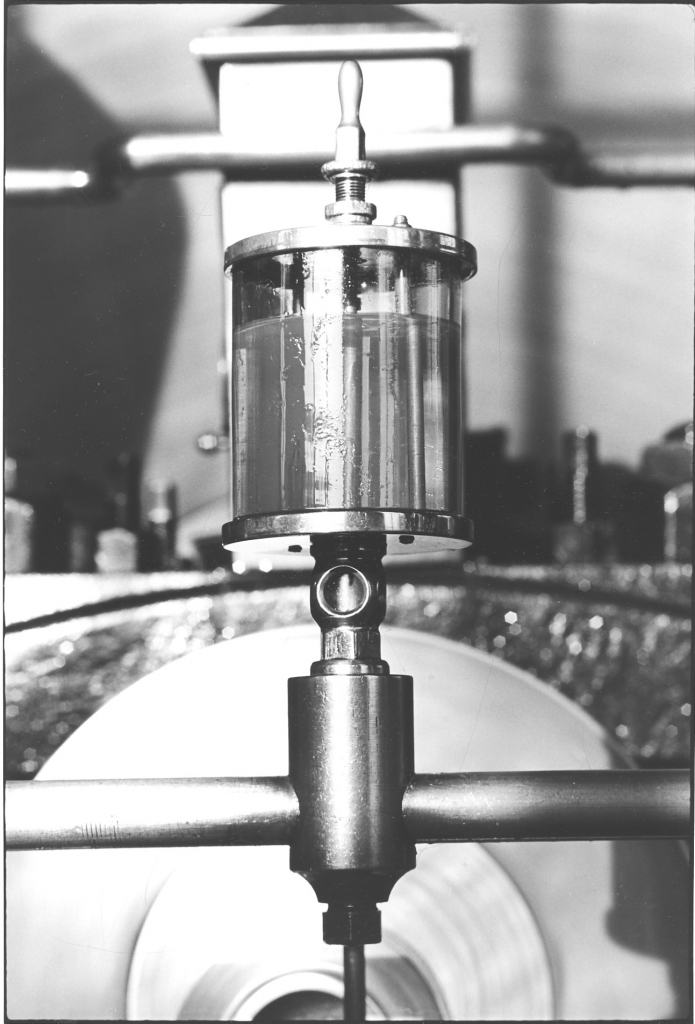

Now this pump is the condenser pump or air pump. Now I’ll just let you have a listen to him (sound of pump working). You’ll notice that that pump is moving at about the same beat, about the same speed as the engine. The reason for that is that it is driven directly off the tail slide of the low pressure cylinder. It is pumping water out of the dam and as it pulls it out of the dam it drags it through the jet condenser. Now the jet condenser is a conical shaped vessel with a ring of holes in the top that the water sprays through so filling it with a spray of cold water, and into the jet condenser the exhaust pipe of the low pressure cylinder enters at the top. Now the effect is that the steam from the engine meets the cold water in the jet condenser, it is condensed, forms a vacuum and the condensed water, condensed steam, the condensing water and any air present which has been released in the boiler or got in through leaks in the engine, on the vacuum side is dragged out of the bottom with the water as it comes through from the dam. It then runs back to the dam and we just circulate it over and over again. The idea of this is to give us a vacuum on the back end of the engine. This vacuum is about 25 inches of mercury in our case which is about –10psi which in fact gives us 10psi of steam free. It has exactly the same effect as raising the pressure of steam at the high pressure side of the engine by 10psi and makes the engine more economical. This was actually James Watt’s greatest contribution to the steam engine I always say. The outside condenser. I should say that the air pump at Bancroft is one of Roberts’s own air pumps and it was always reckoned that they are the worst bloody air pumps in the world. It’s got just about everything wrong with it that an air pump could have. And, it really does need looking after. Without going into the technicalities too much the reason why it in so bad is that the designer tried one or two innovations in the hope that he could improve the air pump because the air pump always was a source of trouble. Unfortunately he had the wrong bloody ideas altogether and he finished up making it worse. The best air pump ever invented actually was the Edwards which - I shan't go into the details of it now, but the piston

(850)

itself had no valves in it. It was just a cone which went into a seating and actually squirted the water through the pump. It were a very efficient, quiet, trouble free pump and it was recommended in about 1930 that this air pump be taken out of Bancroft and that an Edwards be put in in its place but nobody ever got on with it, it was never done. Which is a shame really because the increased efficiency they would have got out of the engine would have more than paid for the pump in the first two or three years. And for ever after that it would have been running at a profit. But there you are, the management didn't feel they could spend the money.

The jet condenser behind the air pump.

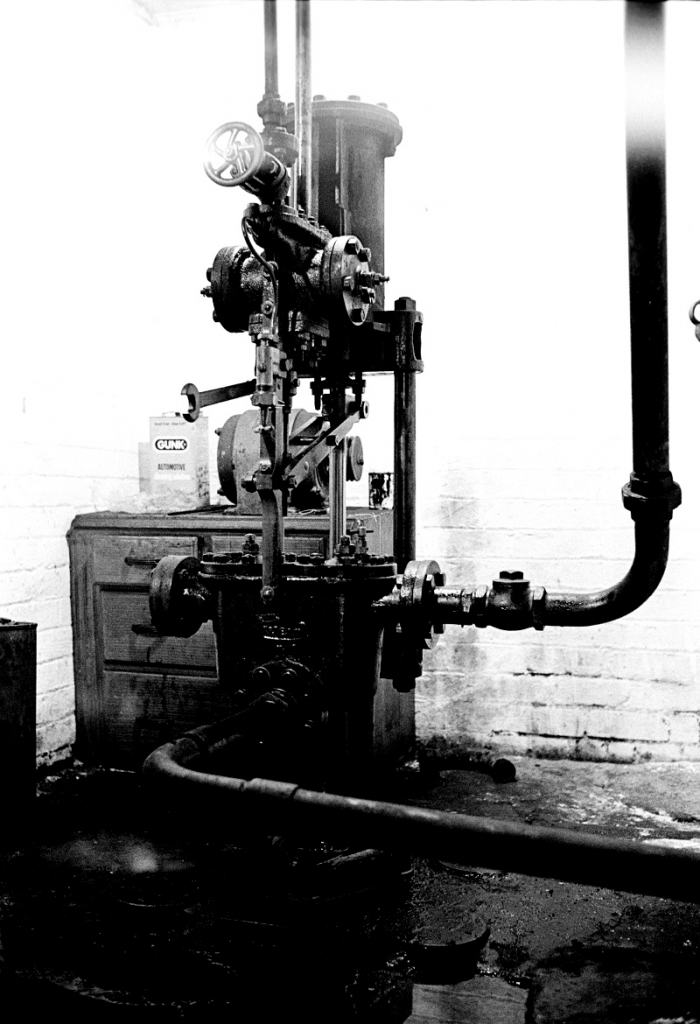

Now we’ll have a walk down the side of the engine bed now and you'll hear a high pitched noise in the background. (sound of the Pearn pump). Now that noise

(40 min)

is the sound of the Pearn pump. That’s Frank Pearn’s from Manchester. Which is pumping water up round the economiser. The water is drawn from the hot well, which is kept topped up with the condensate water out of the air pump, it's then forced up a pipe through the nest of cast iron tubes in the flue - the economiser behind the boiler - and then returned back down to the cellar where another pump actually forces it into the boiler. That's the pump that's just started up. This pump is controlled by a float switch and you'll hear in a second or two it'll knock off by itself. The flow of water through the economiser and hence to the boiler is controlled by a by-pass on the Pearn pump which just by-passes water from the delivery side to the intake side. And that's the other pump stopped, the big feed pump, and by a simple adjustment of a valve on the by-pass you can vary the amount of water going to the boiler from

(900)

almost nothing to full bore.

The Pearn feed pump.

We do have one more pump in the cellar but this isn't running at the moment. This is the Weir steam pump. The Weir is a very good pump, it’s still almost the standard pump in emergency applications, stand by applications. We only use it now if we have an emergency, if all the electric power goes off or a fuse blows, anything like that. What it means is that, as long as there is steam in the boiler we have a means of putting water into that boiler and when you consider that the biggest danger with a boiler is running with low water you can see how important this is.

The Weir steam pump in Bancroft cellar.

Bancroft chimney in 1978. Just a nice feather of light smoke.

Well we are out of the cellar again now, back in the boiler house yard. That's just a short trip round the boiler and the cellar. Of course the other item of interest in the boiler house yard is the chimney. It's a brick chimney, iron banded, approximately 135ft, about 12ft overall diameter at the bottom, about 8ft at the top. The usual taper on a chimney, or batter as they call it, was an inch in three foot. I think this one is probably about that. This is what they call a buttress chimney, in other words the construction is an outer skin of brickwork about three or four bricks thick, a cavity which is split up by buttresses running up inside then another skin of brickwork about two or three bricks thick and then another small cavity, and then the inside liner of firebrick which runs up about the first 30 ft of the chimney. The liner is to protect the bottom of the chimney from excess heat when you are firing hard because otherwise that would crack it. The chimney is made of special bricks, which are made circular with a circular face so that you get a nice smooth cylinder. The way to look after the chimney is to get the steeple-jacks in once a year, I say once a year, that's a mistake, once every 5 years probably to examine the chimney and cover it with boiled linseed oil, give it a coating of boiled linseed-oil. This chimney at Bancroft was done last I think about 6 years ago, 7 years ago. I think about 1971 but I am not absolutely certain of that because the engineer before me didn't keep very accurate records. I think he probably thought the place was on the verge of closing

(950)(45 min)

down and there wasn't much point doing it. And I can sympathise with him because we have been in that position for years. The chimney tapers up for about the first 110 ft to what is known as the string course, which is usually shown by a ring of masonry round the chimney, above that the brickwork is parallel up to the cantilever blocks or buttress blocks, which support the oversail or oversailer which is a rim which runs round just below the top of the chimney. From there on up to the top it's usually called the drum, and that leads right up to the actual top of the chimney. At the top is mounted the air terminal which is a copper rod with three or four points on the top. This is connected by a ¼” thick by 1 ½ “ wide copper strip right the way down the chimney into the ground down to either an old copper vessel or a grid of copper in the ground at the bottom. This is of course the lightning conductor and protects the chimney against any damage by lightning. There is something quite magnificent about mill chimneys, I don’t know what it is. Of course there is the old thing about phallic symbols but they are marvellous things. Nowadays they are finishing, they are going out rapidly. They were built up to 400 ft tall brick chimneys, in incredibly short spaces of time. As I say they are finished now, they are being felled and tin things put up in their place. And there again it’s very sad, I suppose the basic truth is that I'm very old fashioned. I like the old things, but there’s something grand about a good brick built chimney with a bit of ornament on top of it. And I am afraid I can’t find much to go overboard about in one of the new steel chimneys. Well, I seem to have made a pretty good job of judging this tape, we are just about reaching the end so we'll finish now and do the engine and the weaving shed - not necessarily in that order on the other side of this tape.

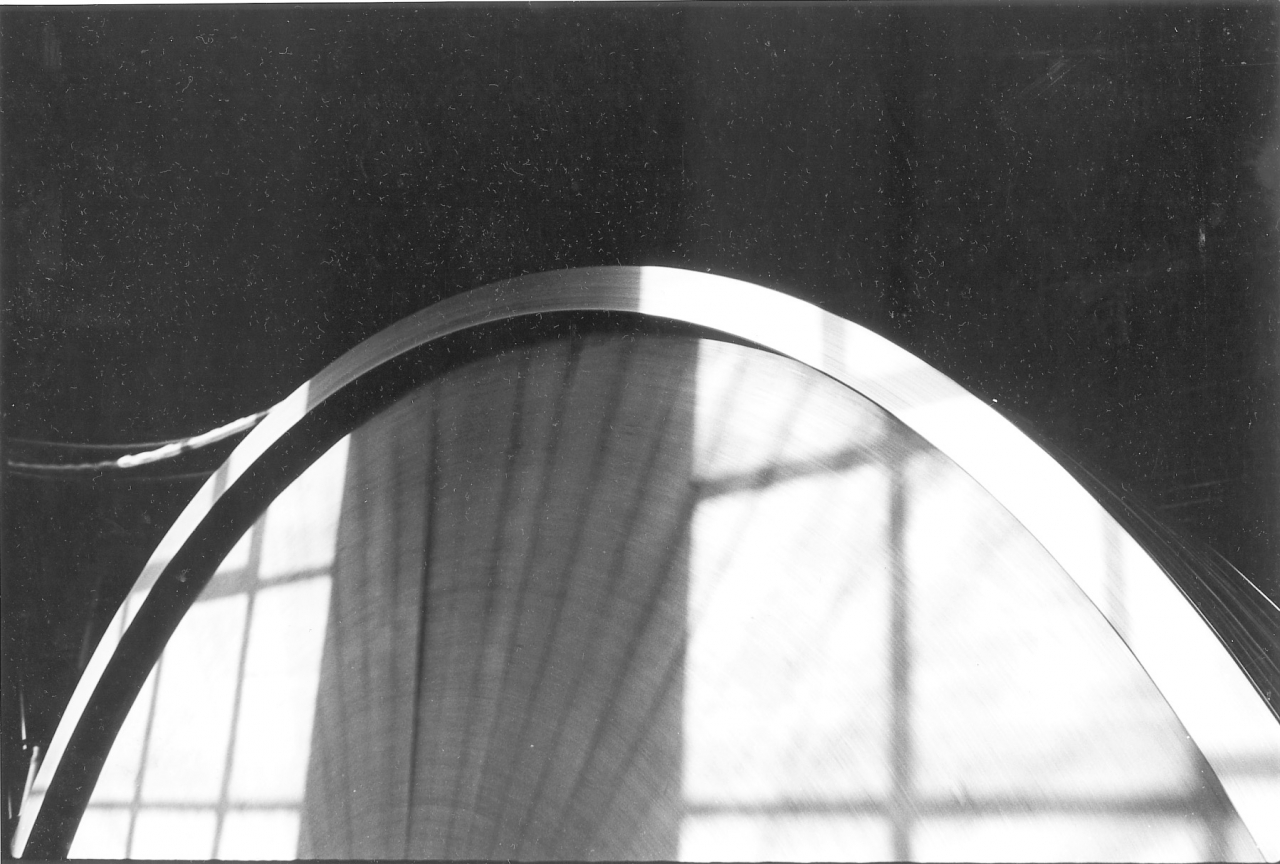

The engine house porch with the mirror that enabled the firebeater to see the chimney top from the firing floor so he could check his smoke.

SCG/03 September 2003

6,195 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 78/AI/02

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON SEPTEMBER 21ST 1978IN THE ENGINE HOUSE AT BANCROFT SHED WHILE THE ENGINE IS RUNNING ON A NORMAL WORKING DAY. THE INFORMANT IS STANLEY GRAHAM WHO IS THE ENGINEER AT THE MILL.

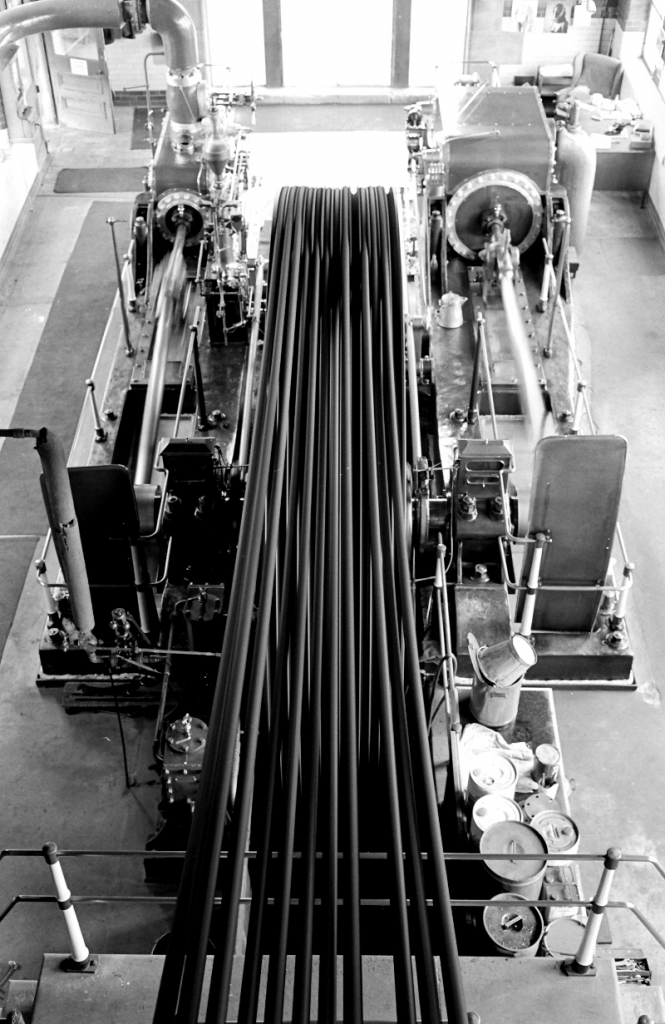

An overall view of the engine from the gantry that carried the travelling crane. And yes, the engine's running and I shouldn't have been up there....

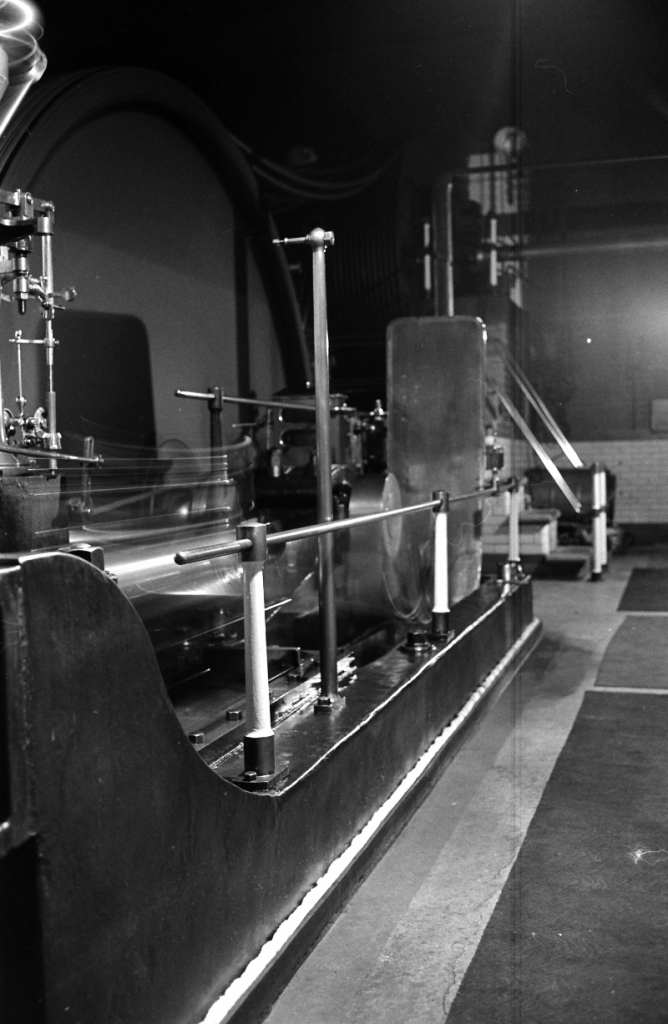

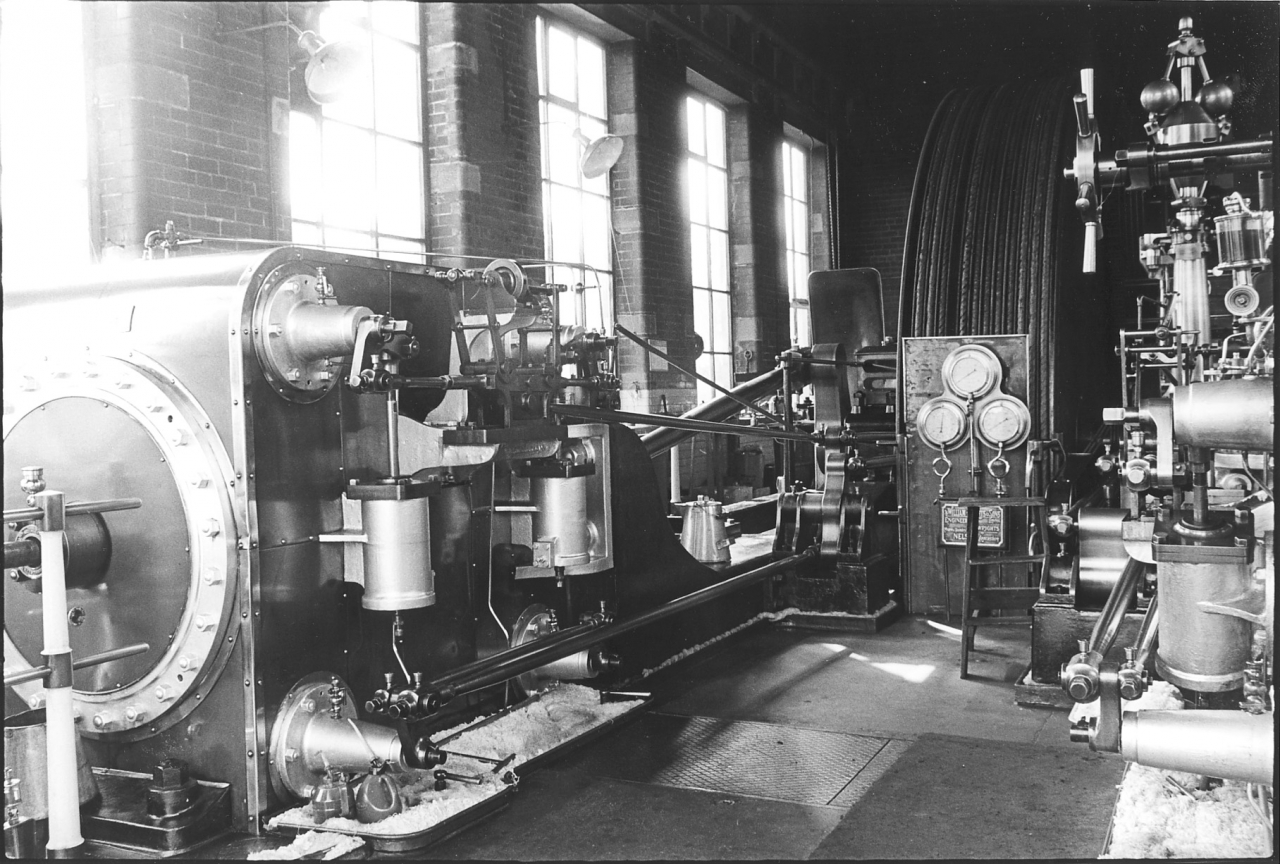

It seems logical to start at the beginning where the power came from. In the background of course you'll be able to hear the engine running away, well not running away, that is a dirty word in an engine house. Running away is when an engine runs out of control. I hasten to add that we are completely in control. I’m standing in front of the big window at the end of the engine house looking down towards the flywheel and the engine. The engine house is approximately 25 ft wide and 80ft long, with a high building, the windows themselves are probably 18 ft, 15 to 18 ft

(50)

to the top of the windows, and then of course the ceiling beyond that. The actual roof of the building is supported on steel trusses and is grey slates boarded underneath, and actually I think this roof will be double boarded, and the inside skin of boards is varnished. It’s almost like a chapel or church roof. The idea of course was to prevent condensation in the roof from the moist atmosphere in the engine house.

The engine in 1978.

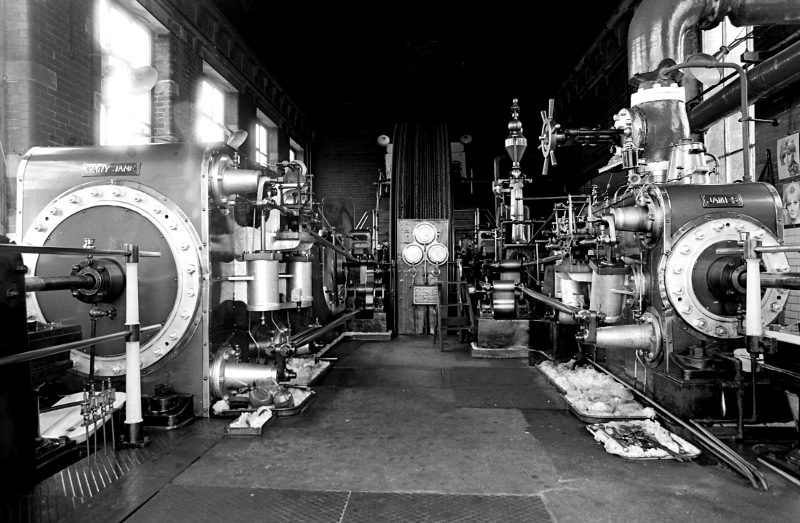

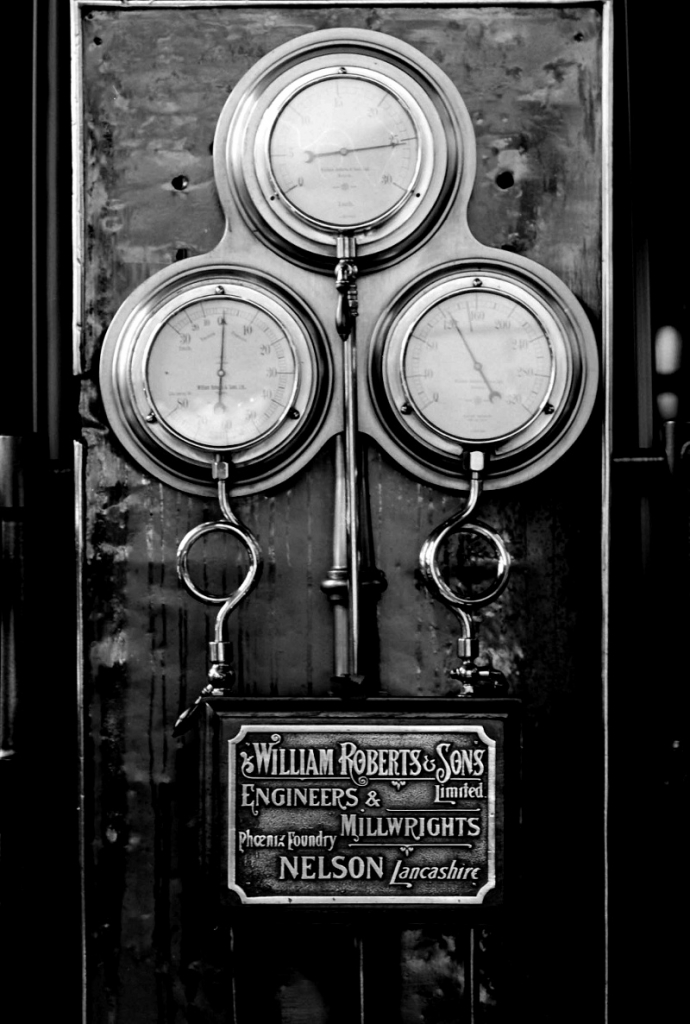

Looking down the engine house, directly in front of you are the gauges, pressure, vacuum and compound gauges and the flywheel.

The gauges with the engine running on a normal day in 1977. Left to right, the compound gauge is showing slight pressure on the LP side, The vacuum gauge is at just over 25" of mercury and the pressure gauge is showing just over 120psi.

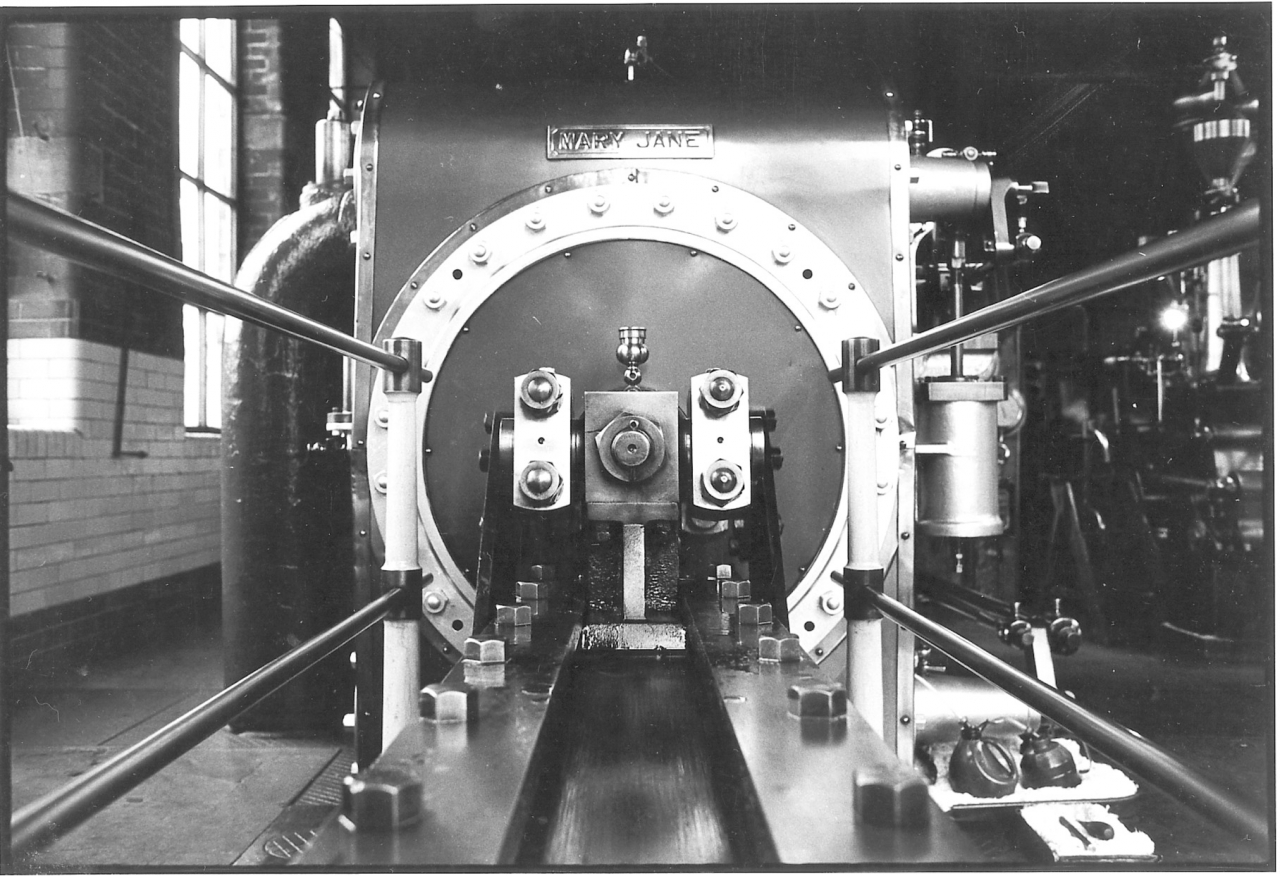

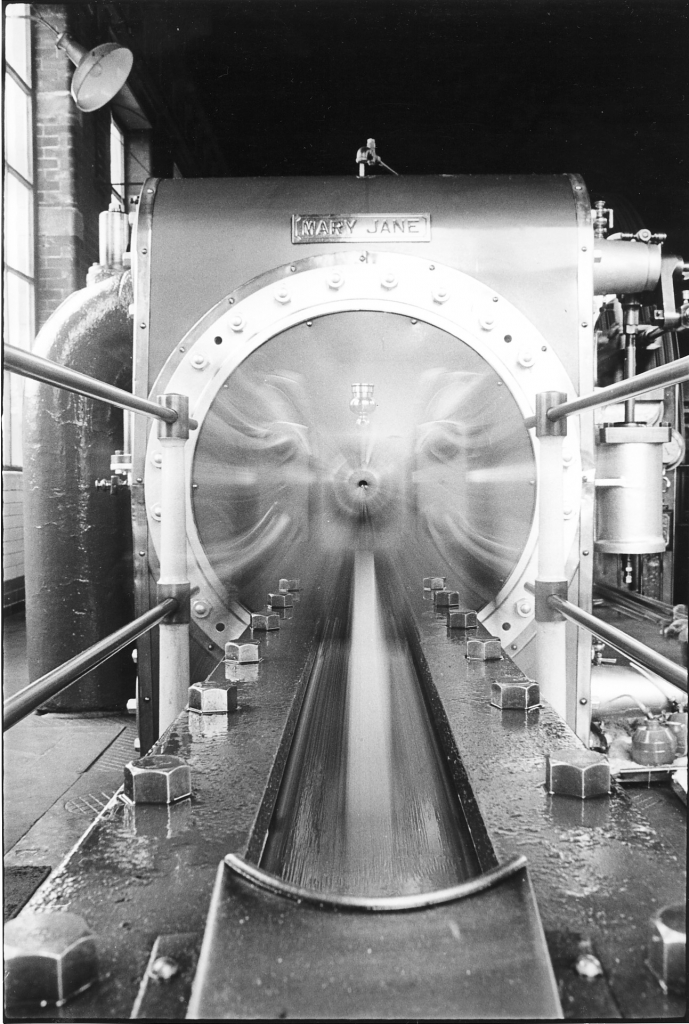

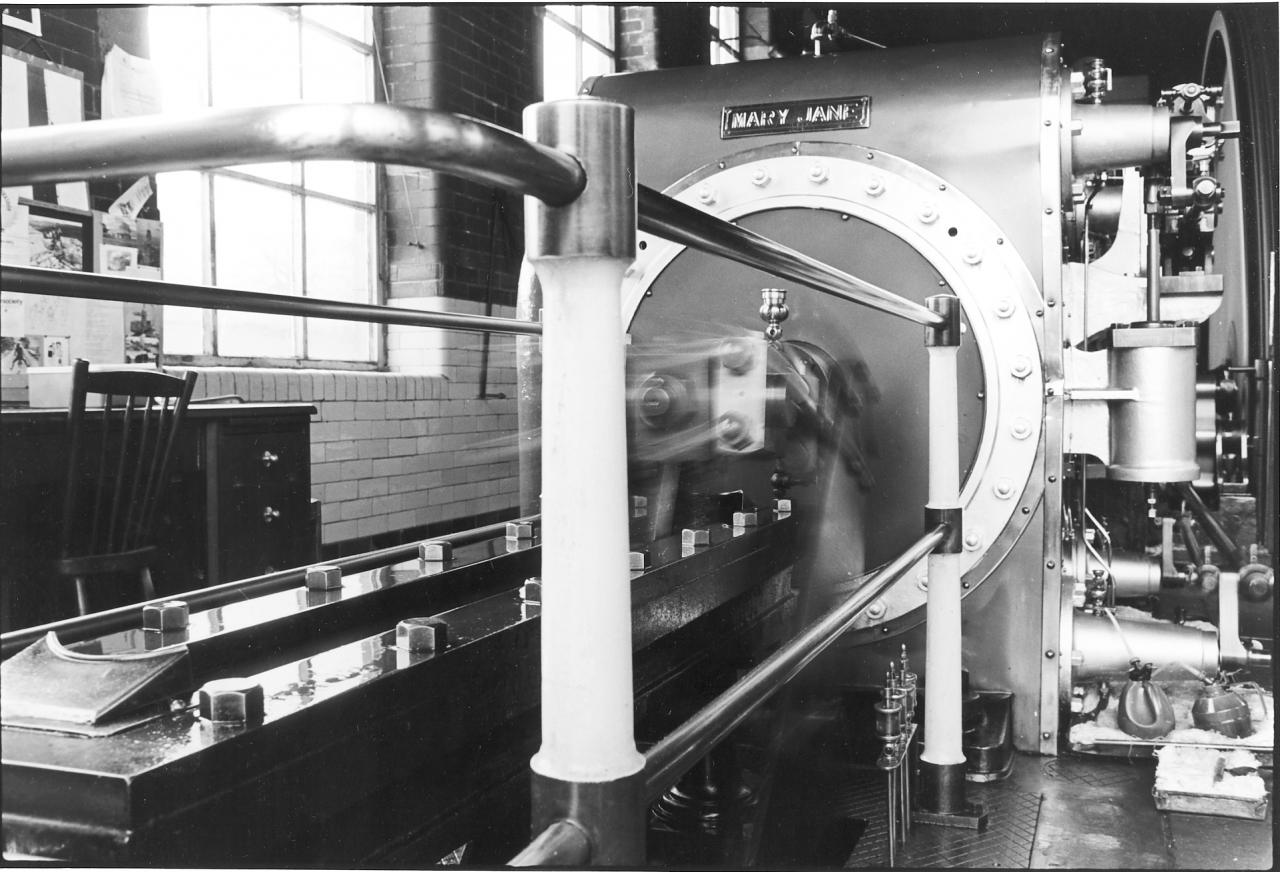

On the right hand side of the flywheel is the high pressure side, on the left the low pressure side. The two cylinders stand one on either side, obviously, about 10 ft from me, James the high pressure and Mary Jane the low pressure. Two tail slides support the ends of the piston rods, the right-hand one is plain on the high pressure side, the left-hand one carries the linkage which drives the bell crank which drives, in turn the air pump in the cellar, which we have

(100)

been down to have a look at. The lubricators that you can see by the railings of the low pressure slide, four on this side and of course four on the other side, are the drip feed lubricators which supply oil to the joints in the bell crank linkage and the bearings on the air pump. On the inside face of both cylinders is a complicated arrangement of levers, linkages and rods, this is the valve gear, Dobson block motion operating cylindrical valves with Corliss gear on them. A lot of people talk about Corliss valves, in point of fact there is really no such thing as a Corliss valve. A Corliss engine is an engine with cylindrical valves, and the valves are controlled by Corliss gear which is a method of closing the valve quickly and accurately. This is effected by a large spring which in held in a dashpot, when the valve opens it puts tension on the spring, when the valve gear reaches a certain point the catch is lifted which leaves go of the rod and allows the spring to snap the valve shut. That is the beauty of Corliss valves, they have

(150)(5 min)

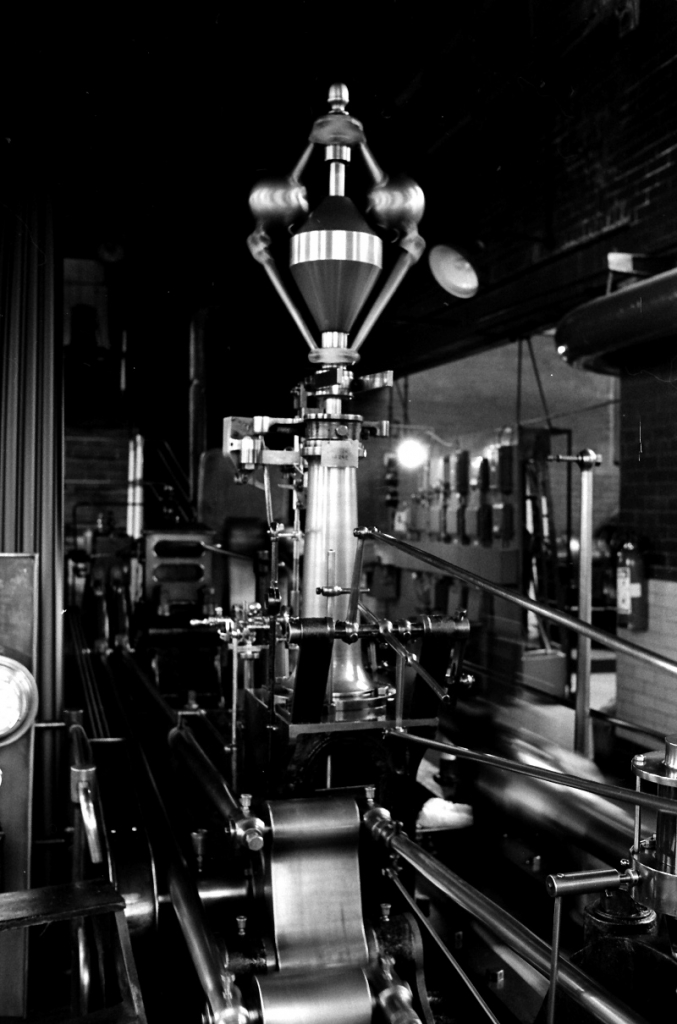

a very quick and positive action. In fact on this engine at Bancroft we have got the original valve springs in which have been in since 1921 and it's doubtful whether the low pressure in particular, is much more efficient than a slide valve now because the springs are weakened and they don't snap the valve shut very quickly. The valve gear on the right hand side, the high pressure, is controlled by the governor which stands in between the high pressure cylinder and the flywheel. The governor is driven by three ropes down the right hand side of the flywheel from a pulley on the fly shaft to a pulley at the bottom of the governor. From there the motion is transmitted by a system of gears to the column through the middle and the governor, bob weights and shaft turn in exactly the same proportion to the speed of the flywheel shaft.

The Lumb governor with the engine running normally.

We might as well get it over with, the old joke about the governor in that as the speed rises the governor's balls fly outwards. For some reason this always seems to amuse the ladies. The action of the governor is self evident, that as the speed rises the balls are pulled outwards by centrifugal or rather centripetal force. As I understand it centripetal is the force which pulls

(200)

them out and centrifugal is the force which tends to hold them in - and there again I might be wrong. Anyway they are thrown out by the force and as they throw, as they try to fly out, they lift a linkage up which raises a bob weight in the middle which is just a way of counterbalancing the power in the balls, and as the bob weight moves up and down it moves the linkage which connects the governor to the valves. The net result is that as the engine speeds up the governor closes the valves down and as the engine slows down the governor opens the valves up thus keeping it at a constant speed. There is also the Wilby speed regulator which takes care of any large drop in load, but that’s really wrong. The Wilby speed regulator is a way of improving the action of the governor. If there was no speed regulator on, the governor would have to control the valves over the full extent of the travel which would mean that a very small movement on the governor would mean a proportionally large movement on the valves. This would mean that the governor was very sensitive and this is a bad thing in a governor as it leads to what we call hunting. In other words the governor overcorrecting one way or the other all the time, it can't settle down to a steady level.

The Wilby speed regulator.

(250)

The speed regulator gets over this difficulty by allowing you to build the governor in such a way that it only controls a very narrow range of the actual valve travel, thus making that governor very steady. Of course this means that if the fluctuation of load on the engine extends beyond the range which the governor can cope with, the governor just can't manage it. Now this is catered for by the speed regulator. In effect the speed regulator alters the length of the linkage rods between the governor and the valve gear. Now this means that the governor controls a fairly narrow range of the engine speed, of the valve openings, and the speed regulator moves that range up and down the total power range of the engine. The total load range of the engine. So that what you have is a very steady governor working on a small range of the valve travel and the speed regulator alters the position of that range in relation to the overall range of the engine power as and when it’s needed during the day. This means that in the case of any sudden load on the engine or sudden cessation of load due to a shaft breaking or perhaps the governor ropes breaking, something like that, it means that the governor can't cope, so there is a safety gear fitted. The safety gear consists of a peg which, if there is a sudden violent fluctuation

(300)(10 min)

of the governor one way or the other, up or down, it breaks the linkage in the actual governor linkage. Which means in effect that the governor rods drop to the bottom, no matter what the governor's doing the rod drops to the bottom and both steam valves on the high pressure are shut or to be more accurate they shut and they are not opened again. This means that no steam is going to the engine, the engine slows down obviously because there is no power. This safety gear is controlled by a system of buttons in the mill and in the shed similar to a fire alarm but all you do is break the glass and the switch flies open, breaks the circuit and a hammer drops and knocks out the safety peg. This is a fail safe device because the solenoid which holds the hammer up is powered by the supply of electricity that comes through these buttons from the mill. If the supply of electricity to these, this safety gear ever failed, the hammer would automatically drop and the engine would stop so it's a fail safe mechanism. If there is any malfunction in the safety gear itself the engine will stop. In fact it isn’t a very efficient way of stopping an engine. An engine is like a train, it's a large mass of weight moving. The flywheel will probably weigh something in the order of 30 tons and it's moving at 68 revolutions a minute. There is something like 300 tons of shafting in the shed

(350)

all moving. It's impossible to stop it immediately. And so, even if somebody presses a button in the mill it'll be at least three or four minutes before the engine stops which would be a long time if you were caught up in a shaft and being dragged round by it. There is one other way of speeding up the stopping of the engine and that is by having a vacuum breaker as well. In other words, when the safety gear itself is tripped, it opens a large valve on the engine which allows air to rush in and break the vacuum on the low pressure cylinder. Because even when the steam's turned off, for a minute or so there is enough vacuum in the system to keep this engine running. And, in point of fact this engine has not got a vacuum breaker on and never has had. I can’t really understand why, I should have thought that every engine would have had one on. But anyway this one hasn't got one and we have never felt the need for it thank God.

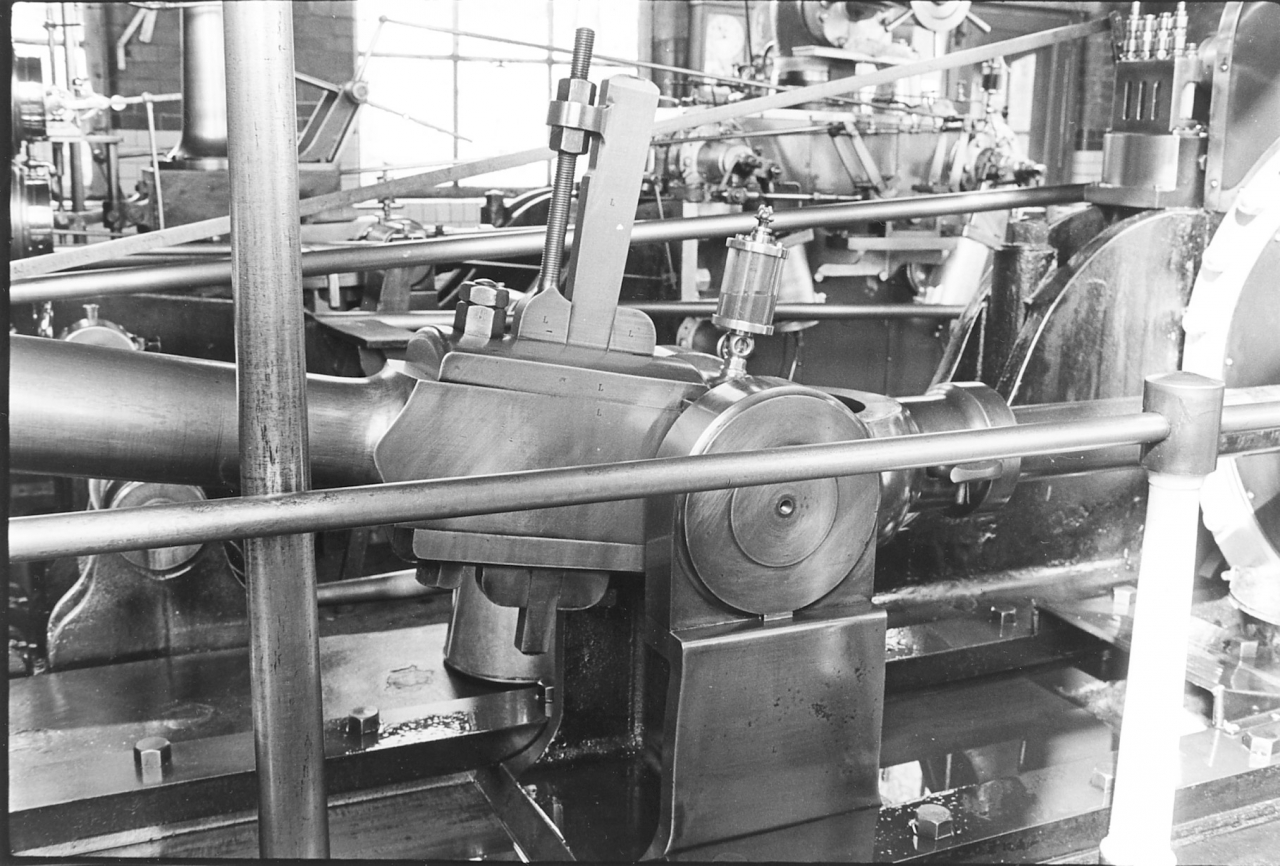

The high pressure side of the engine.

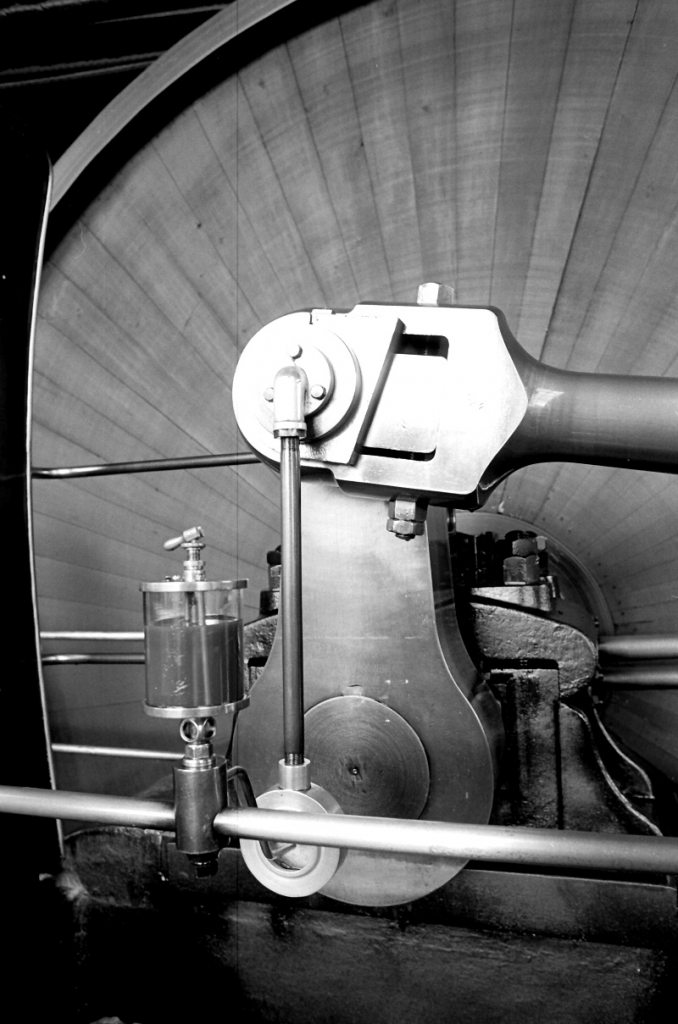

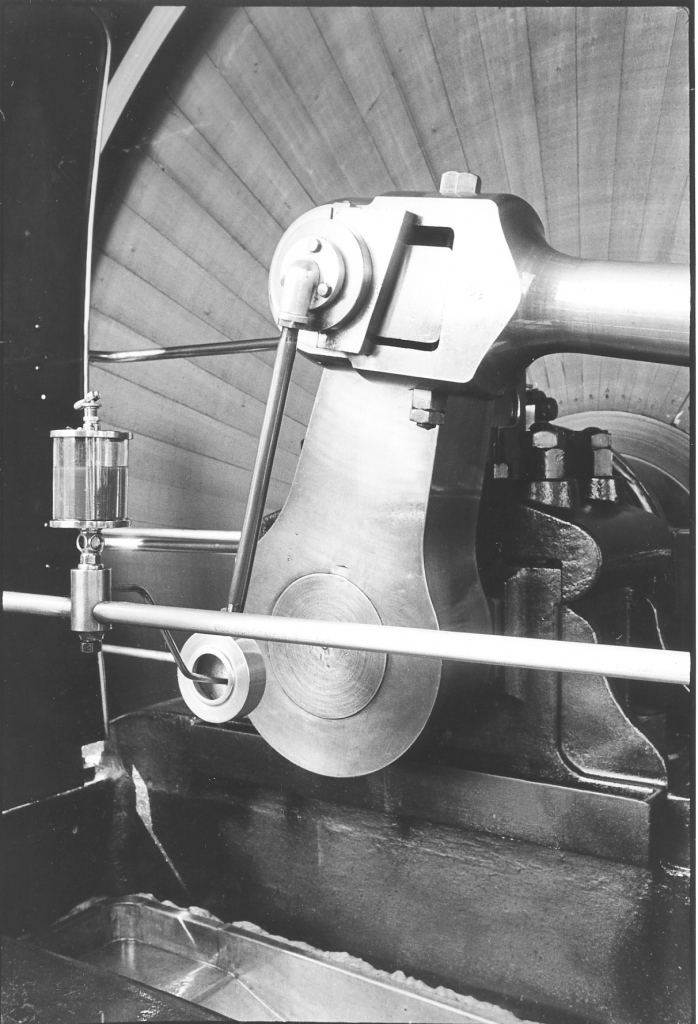

We'll have a walk down the side of the high pressure cylinder now, that’s the engine house door, back side of the cylinder and alongside the high pressure crosshead and connecting rod, the high pressure crank turning the flywheel. One interesting thing about the lubrication of the crankpin, this is lubricated by what we call a banjo oiler.

The banjo oiler on the low pressure side but exactly the same on the high pressure crank.

It’s one of these ideas which is so bloody simple that you wonder why it wasn’t thought of hundreds of years since. A pipe is fixed to the crankpin and runs down the centre line of the crank until it reaches the centre line of the shaft. On the end of this pipe is mounted what can best be described as a shallow cup lay on its side.

(400)

Any oil dropped into this cup can run down the pipe into the crankpin. Now we have a drip feed lubricator mounted on the rail at the side dropping oil through a pipe into this cup. Now remember that the crankpin is revolving at 68 revs a minute, the shallow cup is on the centre line of the shaft, and so it doesn't actually move, it just rotates and any oil that's dropped into that cup is thrown outwards by centrifugal force up to the crankpin. It works its way through the bearing, out on to the drip trays and runs down into the cellar and we collect it there and use it again. So simple, so efficient and trouble free. Having said that, one of the bloody lubricators will bung up and we'll have a hot pin! Just to the right of the high pressure crank is the distribution board which is controlling the electricity which is being generated by the alternator which is the roaring noise you can hear in the background now (sound of the alternator working)

The distributor board and switchgear.

(15 min)

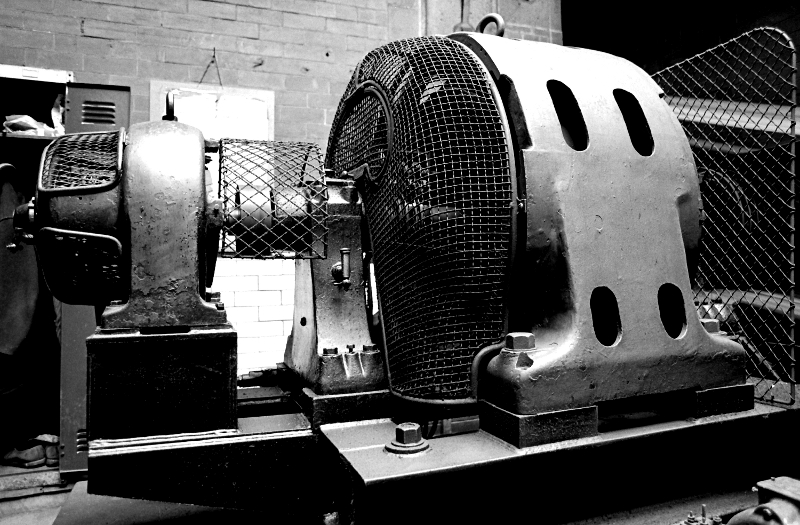

The alternator.

This is a highly important and most uninteresting piece of machinery. All the alternator is, it just looks like a very large electric motor and the only noise it makes is a roaring noise by virtue of the cooling air which is being blown round it. Nothing dramatic happening but it’s actually one of the most important pieces of machinery in the mill

(450)

because that is providing all the electric power that we use. In other words anything that isn’t driven directly off the shaft in this mill is driven by electricity generated by that alternator. It’s a 125 KvA alternator making electricity at exactly the same standard as towns electricity, mains electricity, 440 volts, 3 phase, 50 cycles. Once we start the engine in the morning we switch that alternator in and run on that for the rest of the day, we don’t take any power in from the mains.

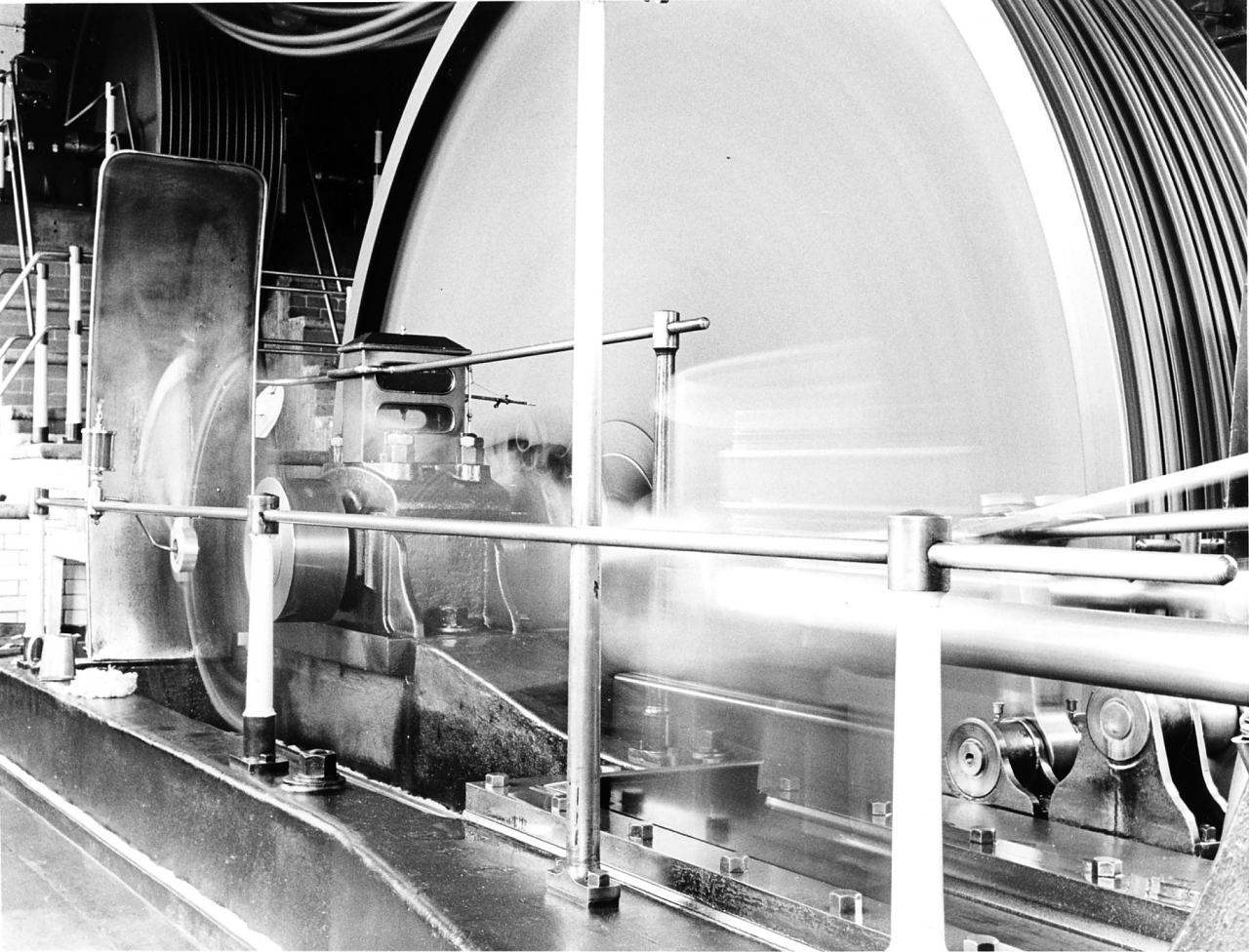

The flywheel.

The flywheel itself has 13 grooves turned in the outside of it. In these grooves run 13 ropes, that's actually a lie because we have only got 11 on, two of the ropes broke sometime ago. These ropes are cotton ropes, they look black because they are covered with tallow and graphite which lubricates them. Good cotton rope drives will last, well it won’t last forever but some of these ropes could have been on 40 and 50 years. The ropes are driven off the flywheel itself, which is about 16 ft in diameter, up to the second motion shaft. The second motion pulley is about 10 ft in diameter.

The second motion shaft.

Now this has the effect of raising the revolutions on the actual line shaft itself which runs from the second motion shaft right the way up the mill and powers everything in the mill. The engine is running at 68 revolutions a minute, the second motion shaft runs at about 150 revolutions a minute. Now it's important to remember that everything is driven off that shaft. The first thing which is driven off it is the alternator by means of a large pulley and a counter drive and then after that everything is driven off by gearing, cross shafts and leather belts. If we walk up to the top of the engine house and just put our head through the door we find that we are stood at the end of the warehouse.

(500)

The warehouse.

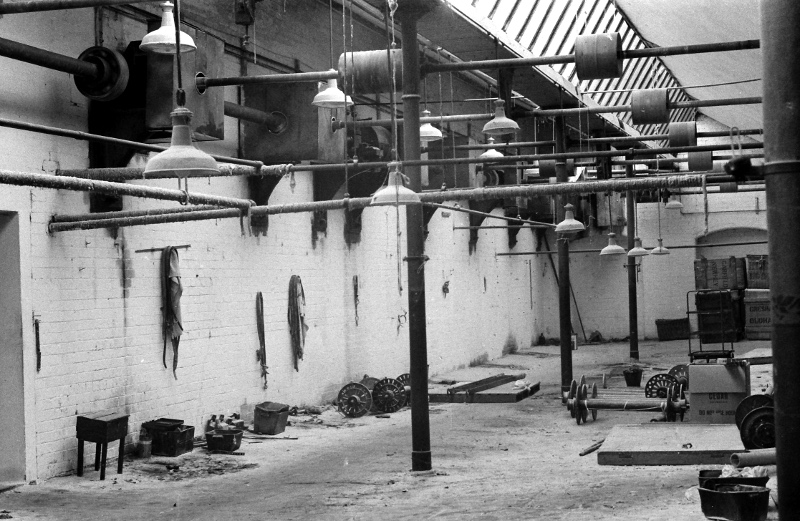

The sound you hear in the background here is the sound of the gearing because on the other side of the wall that we are stood beside, is the boiler house and the weaving shed lies behind the warehouse wall which I face indirectly opposite to the engine house door. The warehouse is a fairly quiet place because there is no heavy machinery in here apart from the shaft running across this end and of course the clothlooking machines at the top end. The warehouse at Bancroft is, to put it bluntly, a bloody mess. There are weft boxes and skips stacked in here which belong to firms which went defunct 20 years since and there is no possibility of them ever going back to their owners. We have wanted to have a clear out for a long while but I don't know, the management doesn't seem to like the idea of burning weft boxes. [I asked Sidney Nutter about this and it transpired that the redundant skips and boxes from mills long since closed down were still on the Nutter books as an asset and if they were written off would adversely affect the balance sheet] The construction of the warehouse is cast iron pillars, cast iron cross girders and a wooden floor, all highly flammable. The warehouse in a cotton weaving shed is probably one of the most flammable places in the world apart from an actual oil refinery. We shall walk up now, through the warehouse and through the shed door and have a look at the weaving shed and the line shaft.

(20 min) (550)

(Noise in the weaving shed)

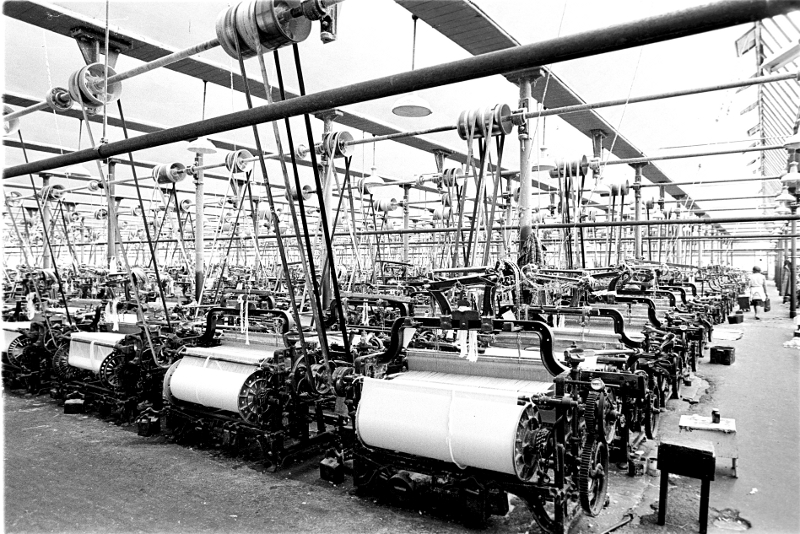

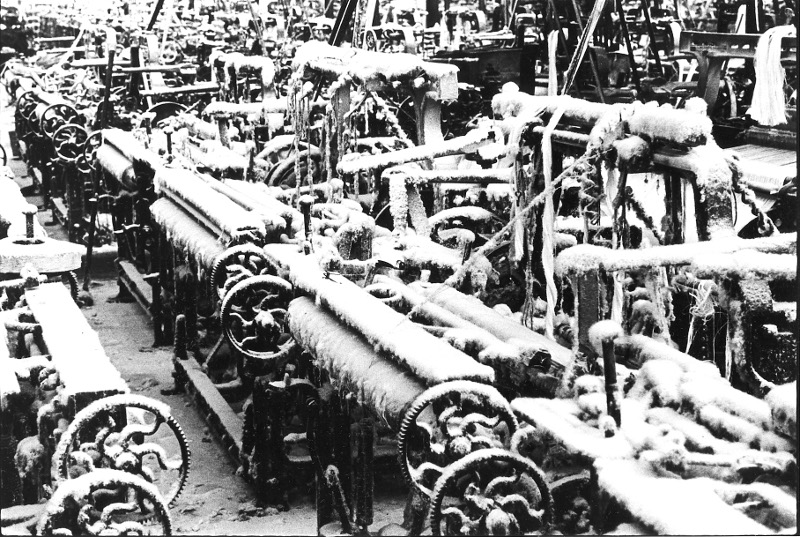

Part of the large weaving shed.

As you probably realise, we are now in the weaving shed. The noise level is very high and I’m going to walk across now and stand underneath the line shaft, then I'll walk slowly up it and you'll hear the shafting (sound of shafting at work). We are up at the top end of the shed now and I'm walking away from the line shaft. I don't think there is a lot of point doing a lot of talking in here because nobody will be able to tell what I'm saying anyway but the sort of noise you are listening to, and you’ll hear in the background now, is nothing compared with what it was like when this shed was full up with looms. Remember there are probably about 200 looms running, in those days there was over 1000. So what I’ll do, I’ll walk out now down past where the looms are running and you’ll be able to hear the sound of looms running which is a different noise entirely from the line shaft. Where the line shaft's more of a roar, looms are a continuous clatter.

The lineshaft from the engine mounted on the shed wall and driving the cross shafts through bevel gears.

(600)

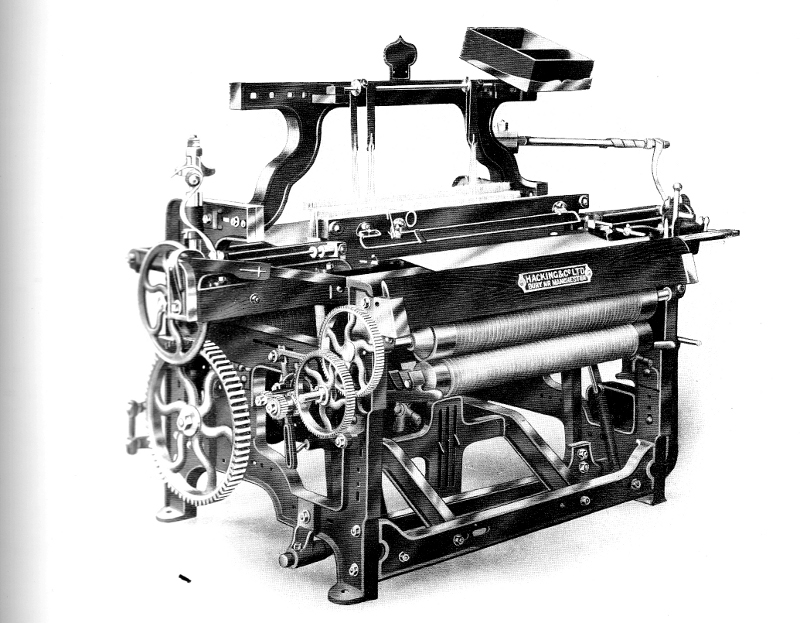

A picture of a plain Lancashire loom from an old catalogue. This gives a much clearer oicture of what one looks like.

And most of the noise comes from the fact that the picking stick is knocking the shuttle backwards and forwards. We'll walk out of the shed now, and I'll talk more about the construction of the shed outside, but we'll go down through the looms which are running (sound of the looms at work).

Well, there you are, that's what a weaving shed sounds like. Well we are back in a sensible place now, out on the engine house steps. You probably wonder from listening to that noise in there how anybody could work in conditions like that. Well I’ll make you wonder even more for a bit. What you can’t realise from the sound recording is that the floor is stone, stone flags, they are sunk, they are pitted, broken, uneven, terrible conditions. It's almost impossible to wheel a truck over them.

The weaving shed in 1977 when it was working. Dirt everywhere, uneven fllors and of course hard work and noise. It makes you wonder how the weavers could stand it but they loved the place.

(650)(25 min)

Everything's covered with a white dust from the size and the yarn from the weaving operation, the lights, all the pillars, the disused looms, it looks like snow. There*s rubbish all over the bloody place. In a well kept shed this rubbish would be swept up but, as you probably gathered, we are not a well kept shed, these things have been neglected for years and years and the accumulation of fly as we call it, this white dust, is just amazing. In places it's like, oh on some looms there is easily an inch, an inch and a half of what looks like snow from a distance, on top of the looms.

One would think that this would probably be an unhealthy thing, I don’t know but I don’t really think that fly is, in the quantities that it’s about in a weaving shed - is all that unhealthy actually. Because there doesn’t seem to be a lot of bronchial ailments. Of course I'm probably not the person to comment on that. It's amazing how people can get used to that noise. The weavers themselves over the years have developed a system that they call ‘mee-mawing’ and it's lip-reading really, they talk to each other with exaggerated lip movements. And I don't know whether you heard as I was walking down the looms there was one noise, it sounded like an owl hooting, and a sort of a ‘yoo-hoo’. Well that's the way the weavers shout to each other to attract each other's attention. They either wave or they make a sort of a hooting noise and that seems to carry above the noise of the looms. Once they have established eye contact they'll start talking to each other across a space of probably, oh, 25 ft, 30 ft, something like that, no bother at all, and they can understand what each other's saying. As I say, that's usually called mee-mawing. You can generally tell somebody that's worked in the mill a long while because the exaggerated lip movements are carried on in normal speech and you’ll find people who talk, and you’ll notice that their lips seem to move far more than other people's. Well, if you meet somebody like that you can bet a bloody pound that they worked in a weaving shed.

Weavers having a conversation while the shed was running. Mostly done ny lip reading.

(700)

I have been heard to say that weaving is probably the second oldest profession. Originally meant as a bit of a joke, I have come to realise that there is probably a lot more truth in that than meets the eye. The weaving industry was founded on the fact that the weavers were there before the industry was. In other words, there was a tradition of hand-loom weaving in the valleys of north-east Lancashire long before the power-loom was even invented. In some families this can go back, well I don’t know how many generations, you can pick your own figure nearly, because I mean, people have been weaving for literally hundreds and hundreds of years. And there does seem to be a very deeply ingrained tradition and this leads to the fact that people can be very happy in a weaving shed. It's amazing when you stop to consider the conditions. I don’t think I have ever seen a happier work-place than the weaving shed at Bancroft Shed, and I mean that quite sincerely. I have thought a lot about this and I can't ever remember anywhere where it has been happier. I've seen places that were probably as happy but never better. There is a very good atmosphere in there and I often think that one of the things is probably that the workers can see an end product for their work, they can see the cloth rolling off the loom. It’s a satisfying thing somehow to actually make something yourself. This doesn't mean to say that the weavers never have any complaints. I mean, the weavers, like any other body of workers, are noted for the fact that they do complain and quite often justifiably. For people in the future who are listening to this, just think about this, it's possible in September 1978 for a person to work 40 hours in that shed and come out with a take home wage of less than £40. And this is something which people even nowadays, many people particularly from the south of England or from the Midlands find very hard to understand. It's even harder to understand when you realize that a mile down the road Rolls Royce'll pay a woman £55 for sweeping up. It makes you wonder why people stick to the shed. As I say, the only explanation that I can give

(750)(30 min)

is the tradition of weaving, the fact that they have the skill, the fact that they like weaving, the fact that probably their friends are weaving as well. And I mean, people do like to congregate together, and just the fact that it is a satisfying job. Another thing which probably has a bearing on it is that a lot of the people that weave here live within 300 yards of the mill, which I should think anybody that's commuting into London and spending three hours on the train every day would say it was a great advantage. The looms themselves are probably nearly all over 100 years old. It’s doubtful whether many would be bought new when Bancroft was built, remember that Bancroft was first built and commissioned in 1921, and this was after the big boom which followed the first world war cracked. Apart from the fact that Nutters, who moved into this shed, were already weaving in other sheds in the town and would shift their own looms up here, there would be plenty of second-hand looms about in good order in those days. So it's doubtful if many new looms came into here. So in effect you can say that most of the machinery in that shed is probably antique, a hundred years old. All the looms are driven from the cross shafts by leather belting. There is a fast and loose pulley on each loom, and power is delivered from the engine through the transmission shafting to the loom by leather belts. The weaver's main job is what we call ‘shuttling’. That’s keeping the shuttle full and running and taking ends up. Now taking an end up is repairing an end in the warp when it goes down. It is said to have gone down when it breaks. So if you have an end down in a warp, meaning you have got a broken end and that has to be repaired or there is a mark in the cloth and basically, that’s a weaver's job. Of course, there is a tremendous lot of skill to it, and one of the big troubles about weaving is that it has never been recognized as the skilled job which it undoubtedly is.

(800)

Up to 1939, the outbreak of the second world war there were plenty of weavers about and there was no need for anybody to pamper them, or even pay them a decent wage to get them to work. It was the only job there was, there were plenty of them about and nobody had any trouble. During the war they were very scarce and manufacturers began to realise how valuable weavers were. But after the war - as you'll have gathered from the other tapes - the consensus of opinion among the people that should know, people like Jim Pollard and men like that, is that that was where the big mistake was made and the weavers weren't retrained. When I say retrained, new weavers weren't trained properly, they were put on to looms in three weeks in some cases and a lot of the old skills gradually died out as the old people died. Anyway, I'm not going to encroach an Jim’s subject about weaving. I’ll talk now about the construction of the shed. Bancroft Shed is what is known as a girder shed. The main components of the structure are the walls, cast iron pillars and continuous cast iron girder gutters. Now in other words the gutter between the typical saw tooth north lights. The valley gutters are the structural members which support the roof of the shed. They in turn are supported by cast iron pillars which stand about 10 ft apart one way and 15 ft down the run of the gutter. It's a very good construction, very sound construction, the roof is slated on the south light, and glass on the north light and Bancroft Shed is one of the few sheds which is a true north light shed. In other words the sun never shines into it except during the very middle of summer, perhaps about 8 o'clock at night some sun comes in through the glass. But otherwise, the sun never shines in, you get a good diffused north light all day. It's actually a perfect artist's studio and this of course is what you want for weaving, good even light. The shed can get very hot during summer for this reason so at the beginning of June each year we whitewash the roof. When I say we white-wash the roof, we should actually white-wash the slates and the glass but being Bancroft we can't afford that, all we do is white-wash the glass.

Whitewashing the shed roof North light windows

(850)(35 min)

The idea is to stop some of the heat being transmitted in from the sun and by reflection off the slates. The sun doesn’t actually shine straight in [because Bancroft is a true north light shed roof] but a tremendous lot of heat is reflected in through the glass off the slates of the shed roof. I can vouch from personal experience that the slates on the shed roof can get that hot you daren’t bear your hand on them during summer. A grey matt surface will absorb heat very well. One of the main features, which strikes everybody when they go into the shed, apart from the noise, even if the shed is stopped, is the fact that it is very nearly monochrome, there is very little colour in a weaving shed. Whitewashed walls, grey iron, black cast iron, white cotton, white dust. Virtually the only colour is the brown of the healds and occasional splashes of colour where a weaver's left a cardigan hung over the back of a chair or over a box. That is in passing another feature of a weaving shed in that each weaver has a chair or a stool or a buffet or a box at the end of the alley.

A weaver's buffet at the end of her alley.

And in the infrequent periods when all the looms are running and they have got two minutes they'll sit down on there, and they sit down on there for their meals as well. The canteen, or what is nominally known as the canteen at Bancroft, is actually just a room with a steam-oven in it and nobody really likes sitting in there. About the only thing it's used for is going and having a smoke during the day. Most of the weavers either pop home for their dinner or sit at the loom. One thing about sitting at the loom, you always have a clean tablecloth, because obviously they use the cloth on the loom. It is a truism that a weaving manager likes to go into the shed and see the weavers sat down because that is when they are making money. Because a good weaver isn't sat there if there is any shuttling to do or any ends down. So if the weaver's sat at the end of the alley it means that everything's weaving all right and there is cloth rolling off. In other words, as long as they are sat down it's 100% production. When you come to think, this is true of a lot of other trades as well. I know if I was employing a man and he was for ever rushing around in small circles I’d start worrying about him. I like the men that always seem to have plenty of time. And that's one of the things about weaving, a good weaver is a joy to watch, there isn't a movement wasted and every chance they get they’ll sit down and take a rest. And they seem to work round in a rotation, even on different weights of twist and different weights of weft, where shuttles aren’t lasting the same length of time, they seem to be able to

(900)

keep up a routine and a rotation round the looms. This means that they never have to run from one end of the alley to the other. Just one of the little skills that goes to make up a good weaver and we have got some good weavers here, we have some bad ones but we have some good ones. But I’m afraid they are dying out, nobody's training them now. Apart from anything else, in order to train a weaver, the weaver has to have an incentive to work, and probably that's one of the great things that’s missing now, there isn't the same incentive to work as there was. Take our position now, we are going to be redundant on the 22nd of December. We are told that we'll get redundancy money, earnings related supplement, the dole, tax back, I don't think there’s, most of us in this shed, we actually will be earning more money on the dole for six months than we would if we were working. Which in many ways is a fine thing, I'd rather have that than the hungry old days, but in other ways it's wrong, people should have to work for their living. Well, I am sat back here in the engine house, I think that's about it for the sound effects of Bancroft. It’d be very easy to go on and talk for hours and hours and hours, there are different aspects of the job and different ways we have been affected by this week's news. If 1 sound a bit depressed this morning that’s probably the reason why, the news that we we’re to close down on December 22nd didn't actually shock anybody I don't think but it's sad. I mean I sit here now and look at this engine, installed in 1921, just about run in and good for at least another 100 years. And on the balance of probabilities it'll most likely be scrapped inside 6 months. Scrapping an engine is murder, especially when you have had something to do with it. Because a steam engine like this is very nearly alive. I don’t know what it is about it, I've often puzzled. I think part of it's gentle giants, everybody likes elephants and big blokes, big ships, steam locos, gentle giants that's something to do with it. They are warm,

(950)(40 min)

they keep you warm in winter. Lovely things to work on, plenty of room, plenty of stuff to polish up - not that I have ever been noted for going crackers with the Brasso! I'd rather keep them running nice. You can hear this engine running quietly in the background, it's running beautifully. A little point there, no doubt the more technically minded amongst the people who listen to this tape will have heard about indicating steam engines.

Stanley indicating the engine in 1977.

There's probably been more written about the indication of steam engines, which for the uninitiated is a way of finding out exactly what's going on inside the cylinder as an aid to valve settings and diagnosis and all the rest of it. There's probably more been written about indication than any other single subject concerned with steam engines. I'm afraid that I am here today to tell you that the biggest part of it is all a load of tripe. There’s a lot of difference between the theory of running a steam engine and the practice, and I should think this is the same in every other walk of life. It’s possible to adjust the valves on this engine to give a perfect indicator diagram and the engine will run like a basket full of bloody pots. There is only one thing that counts, how evenly the flywheel is being turned. And really that’s basically all you need to know about whether an engine is running right or not. It's easy to tell with a rope drive engine, when you go into an engine house if there is a rope drive just look at the ropes. If they are swinging across to the second motion pulley in a big smooth curve and hardly kicking at all, just gently rising and falling, that engine's all right. But if you go into an engine house and you see those ropes flogging about and jumping up and down, either they have been very unfortunate and they have got a very bad rope drive, in other words the harmonic frequencies in the drive are wrong, or they have got a badly adjusted engine, most likely the latter. So, the rule about indicating is that it's a good thing to do every couple of months just to give you an idea of any faults that are developing but it certainly is not the ultimate guide to valve setting. There are so many things which can affect the running of a steam engine and really the only way to get to know is to sit with them and live with them as I have with this engine for the last five years.

(1000)

As I say, in three months all this'll be over and it's very sad. You have got to make a conscious effort not to actually, I wouldn't say go into a decline, but you have got to harden yourself against the knowledge that everything that you have looked after and cared for is going to be smashed up. It killed people in the old days, some of the old engine tenters just went into a decline and quietly died when they smashed their engines up. I can understand it. I must admit to being depressed myself this morning, it’s a couple of days now since we got the word and it's just about sunk in. So now what we have to look forward to is decline. It'll finish up that there'll just be Jim Pollard, Ernie Roberts on the last set of looms and me running the engine, and John Plummer on the boiler. There'll be four of us. And, we'll have the job of killing it. I say we'll have the job of killing it, we won't actually, I shan't because I have already told Newton Pickles from Brown and Pickles that he can stop this engine. It's the last one he worked on, all the others have gone so I think it's only fair that he should stop it. When this engine stops it'll be the end of an era for Barnoldswick anyway, the last engine in Pendle and the last of the big weaving mills in Barnoldswick. This town used to have 25,000 looms to 11,000 people and when Bancroft stops that's it, there'll just be two little units, one with about 80 loom and the other with 98. Really, what we are seeing is the end of the first stage of the industrial revolution. In some ways I am glad

(45 min)

I've been here to see it. In fact I am very grateful for the chance that I have had to record the finishing up but in other ways I am very sorry because what started off as just an interesting job and a pleasant exercise has become for me, the same as a lot of other people in the industry, a way of life and there is going to be a big change in my life when this engine stops. Anyway, I suppose we'd better look to the future and remember those famous words of Walt Fisher, “When they did away with the engines, they did away with a lot of bloody hard work.”

(1052)

SCG/04 September 2003

6,334 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 78/AI/03

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON DECEMBER THE 12TH 1978 IN THE ENGINE HOUSE AT BANCROFT SHED. THE INFORMANT IS STANLEY GRAHAM WHO IS THE ENGINEER AT THE MILL.

John Plummer my firebeater. Not just a good firebeater but a good friend. We never had a wrong word and I miss him.

Just a few thoughts today on what it's like to be working in a mill that's weaving out. The only people who are working normally now are myself and John Plummer the firebeater. When I say normally, we are the only people who are doing exactly the same job that we have done for the last 5 years and of course, which has been done ever since the mill started. We are still making steam, running the engine and producing power to drive all the mill. The difference being that the load is now much reduced, the actual driving load is reduced, there are very few warps left in the shed, most of the weavers have three, four or five looms empty. All taping has stopped, looming's stopped, winding is very nearly finished, there are no yarn deliveries, no back beams coming in. The only wagons that come in now are vehicles taking empties out to take them back to mills so that we can draw the deposits on them. We did send one other delivery out the other day

(550)

which was a very sad one. We had sold some looms. Sutcliffe and Clarkson's at Wiseman Street in Burnley, who still run on a steam engine bought some looms off us to complete an order for us which they will take over and weave themselves afterwards. It’s a very steady order for some very strong cloth. The heading here is ‘Two Brown’, it's a very strong pure cotton cloth. I’m not sure what it’s used for, I think it's used for polishing buffs in the metal finishing industry.

The looms leaving Bancroft for Sutcliffe and Clarkson's.

The big laugh about this was that the day we delivered the looms there was a big headline in the Evening Star at Burnley that Stayflex, the firm which owns Sutcliffe & Clarkson, had gone bankrupt that day with a deficiency of £6,500,000 which left us in trouble in several ways. One was they had got our looms and we hadn't got the money. The second was that they weren't able to complete the order and we’d have to find somebody else to complete it and the third was of course the fact that the same firm Stayflex, the same firm that owns Sutcliffe & Clarkson's, also owns one of our biggest cloth customers and we have a lot of cloth in the warehouse ready to be delivered to them.

Sutcliffe and Clarkson's cloth in the warehouse in 1978.

We had known that they were rocky for a bit and when I say rocky we have known that they had been in low water for a bit and we haven’t delivered any cloth to them unless they have paid for it first. Well now of course we have a load of cloth stood up there, at the top of the warehouse which in never going to go out or at least not to that firm. It is a fairly

(600)

common cloth and we’ll probably be able to find another customer for it but not before December 22nd, so we shan't finish up with a clearance of cloth in the warehouse. An interesting point about Sutcliffe & Clarkson's closure is that the original owner of the firm, Reg. Clarkson who has about two years to do, still works there as a manager and the last information we had was that he had gone to Leeds to try and buy the mill back off them! [The Receivers] Because Sutcliffe & Clarkson actually is one of the few mills in this area

(5 Min)

that is full up to the doors. They have 500 looms and they are working flat out and making a profit. And he said he didn’t see the point in throwing 150 people out of work just because Stayflex themselves have gone bust. Whether he actually will buy the mill back is anybody's guess, I don’t know. But they have told us they are continuing trading, that they will weave the order and that we will get paid for the looms. This is Sutcliffe & Clarkson of course and not Stayflex which looks vaguely hopeful. News of another closure yesterday, Greens at Whalley, Abbey Mill, also a steam engine, the firm that offered me a job in October or November, they are to finish in March. It’s only about three weeks since that Newton Pickle was down there weighing everything up and quoting them for electrifying the shafting, in other wards putting an electric motor at the end of each cross shaft in the shed to drive the looms. I think the quotation was for about £2,300 for each shaft. That was for a 30 HP motor, Horace Green’s motors from Cononley, and necessary alterations to the shaft, bearing and wall plate. I asked him at the time whether he thought this would ever be done because to my knowledge, this is the fourth time that Greens have been quoted for electrifying the mill because the engine has been in a dodgy condition for a long while. And he said that it looked as if they were going to do it this time, there you are, it’s not going to happen.

(650)

Another interesting point that has emerged is the fact that we are not the only firm that is being closed down after being bought out by Indian money. It appears that Indian money is coming into Lancashire in order to buy cotton firms out and close down the weaving section of them. It makes you wonder whether they can see their costs rising and they realise that in 5 or 10 years Lancashire textiles are going to be competitive again. Before this happens they are making sure that the units of production are lessened as much as possible. It won’t be costing them any money actually, because they'll be stripping the assets and they'll get back just what they paid for them. All clever stuff, I have no doubt that we have done it from time to time in other places, they appear to have learnt very well off us! I was talking with a traveller the other day, and he tells me that he knows of at least 12 firms who have been closed down this year in this way and we are one of them of course. Be that as it may, we are left in the position of running this mill now until Friday December 22ndp or such time as no weavers turn in, the reason I say this is that I can't see us running until December 22nd. All redundancy money is to be paid out on Wednesday 20th, all holiday pay and wages owing. They are going to estimate the wages and pay everything out on Wednesday December 20th. So in other words Wednesday December 20th is going to be the last time any of us draw any money off the firm of James Nutter and Sons Ltd. I can't see the weavers coming in Thursday and Friday to weave in a shed when they could be out doing their Christmas shopping because Friday is the last shopping day before Christmas. There is of course Saturday, but who wants to go shopping on Saturday? So in all probability this engine, this mill will

(700)

virtually cease to weave on the Wednesday evening, fairly early I should imagine. Thursday we’ll probably have three or four weavers in, we might start the engine, but I don't know, Friday certainly not, I can't see it. It'll be a big shock to me if we ever start this engine on Friday. There is some bright news on the scrapping situation, there seem to be every possibility that the mill has been bought out by a man called Malcolm Dunphy who owns the firm of Dunphy Oil and Gas Burners, Regent Street, Rochdale. The contract hasn't actually been signed yet but he has put a bid in which has been accepted and he seems confident that he has bought the place. He has bought it 1ock stock and barrel, everything, looms and all, and he will scrap everything himself except the engine and the boiler. He intends to use the boiler for testing burners on, and with the steam that that produces he is going to run the engine, to drive the alternator to make the electricity to run his firm which at the moment is fairly small, but he can always put a bigger alternator

(10 min)

in if he expands. I think this is a feasible scheme, and I think that he’ll find that it’ll be all right. He'll no doubt run into snags with fluctuating steam pressure and fluctuating load, but I should say there is every possibility that they’ll be able to cope. An interesting thing about this is that Malcolm is a man who runs a Rolls Royce and who flies round in a helicopter and we have had the interesting experience of having the new owner of the mill landing in a helicopter in the field at the back of the mill, which is a very good example of being dragged screaming into the 20th or 21st century, a steam engine running in the mill and a helicopter landing in the field behind. Two different ends of the spectrum of technology. Very interesting, nice little comment on the way the world works.

Malcolm Dunphy's helicopter at Bancroft in 1978.

Redundancy has always been a sore point with me, because I think that many a time the fact that a person expects a redundancy payment encourages them to stay on in a dying industry longer that they should.

(750)