TAPE 78/AC/1

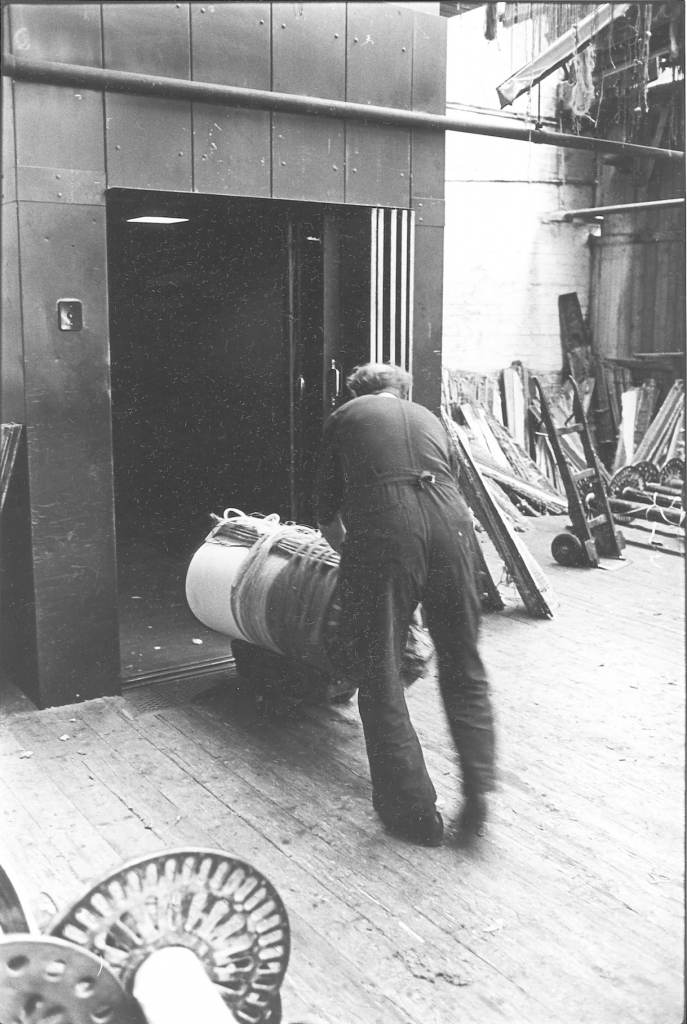

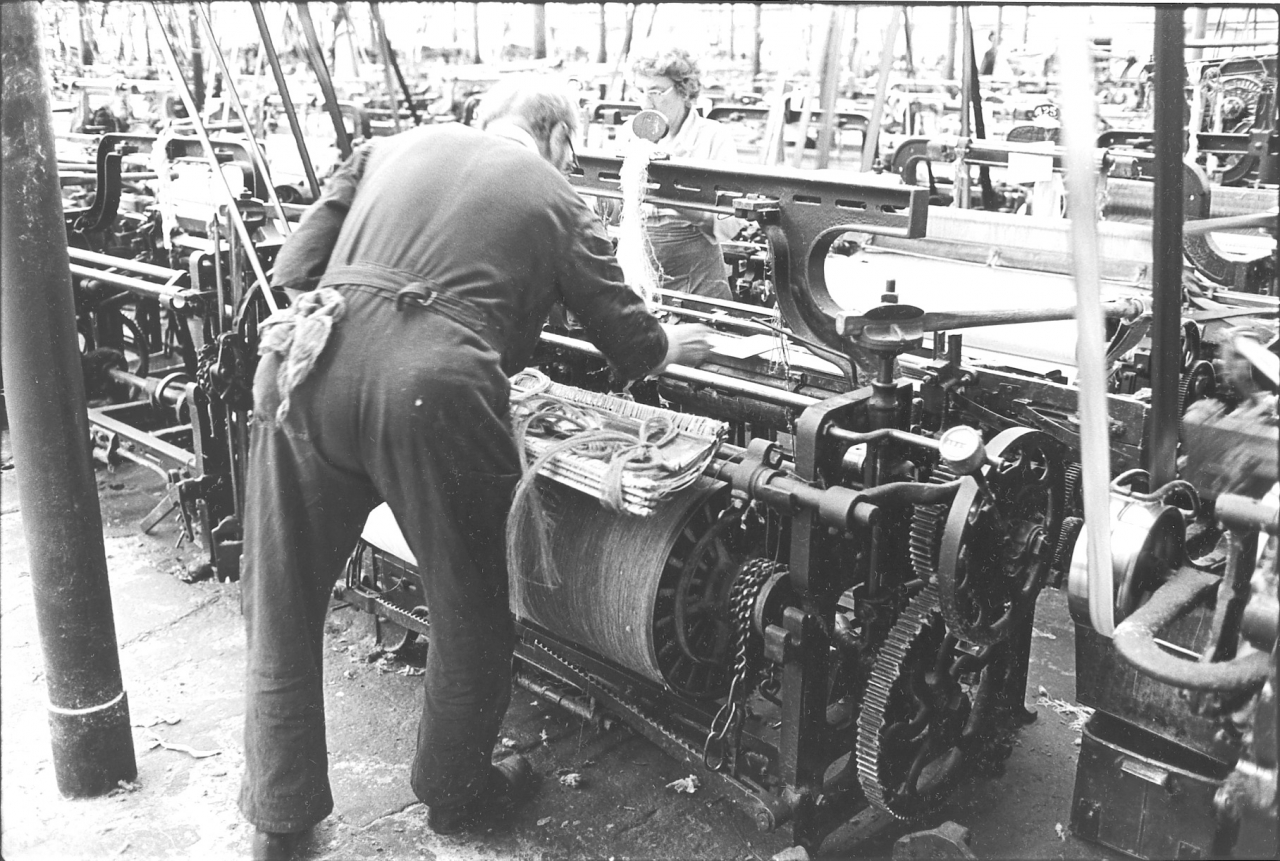

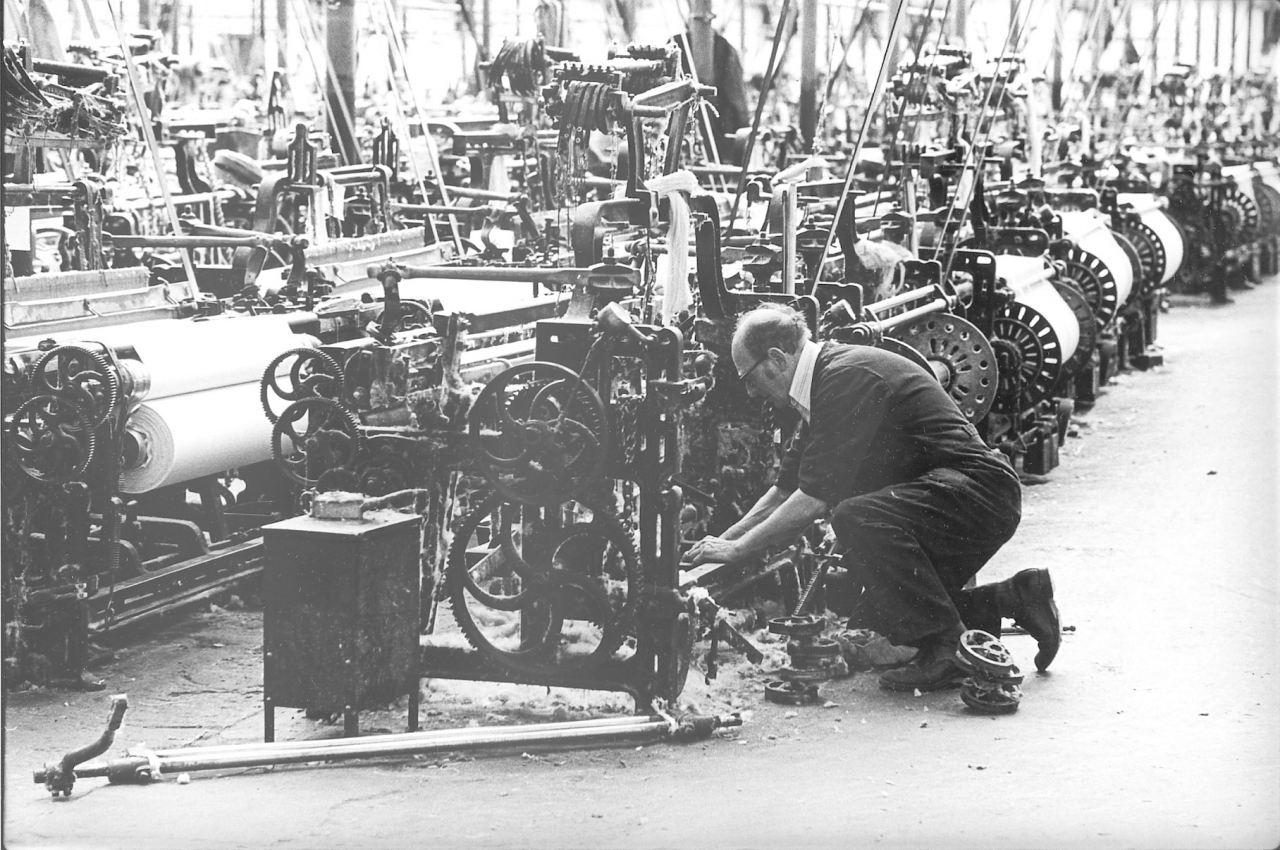

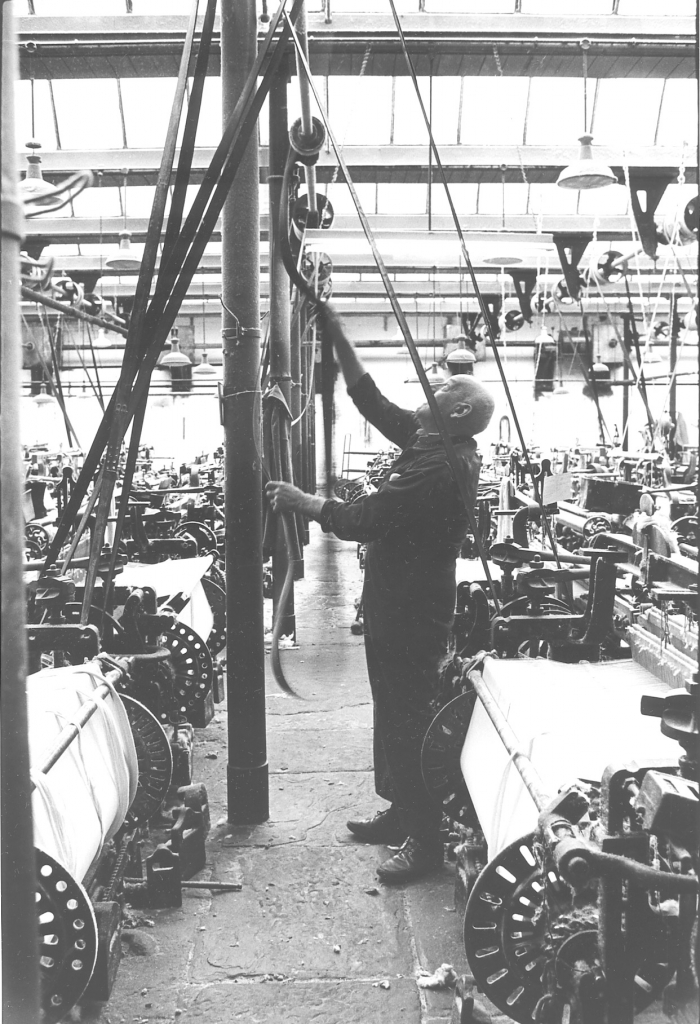

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 15th of JUNE 1978 IN THE ENGINE HOUSE AT BANCROFT SHED, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS ERNIE ROBERTS, TACKLER AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

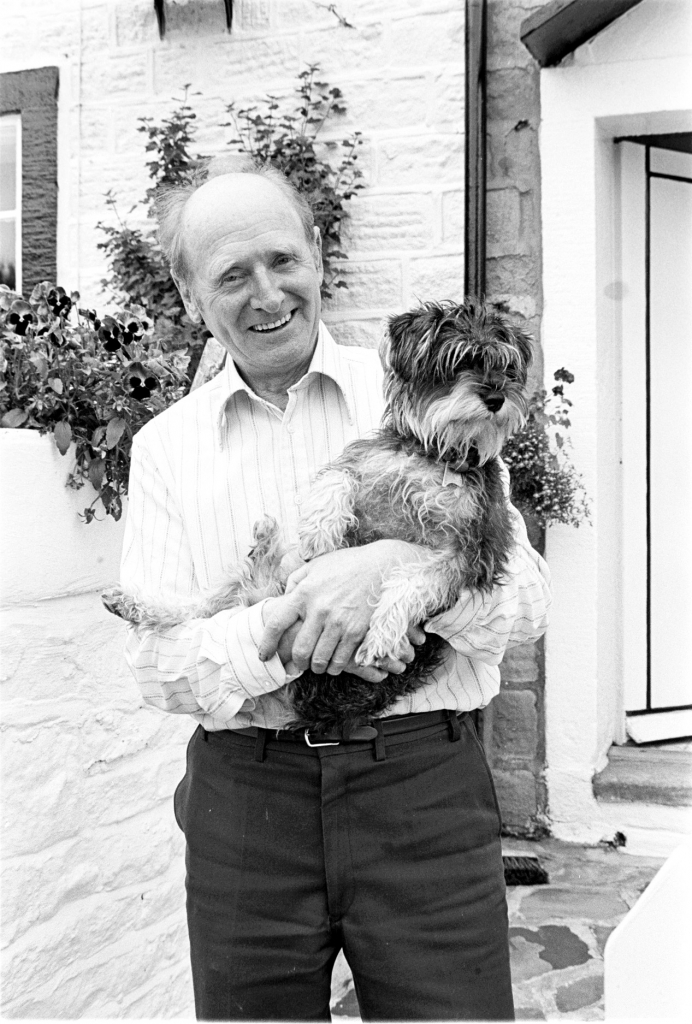

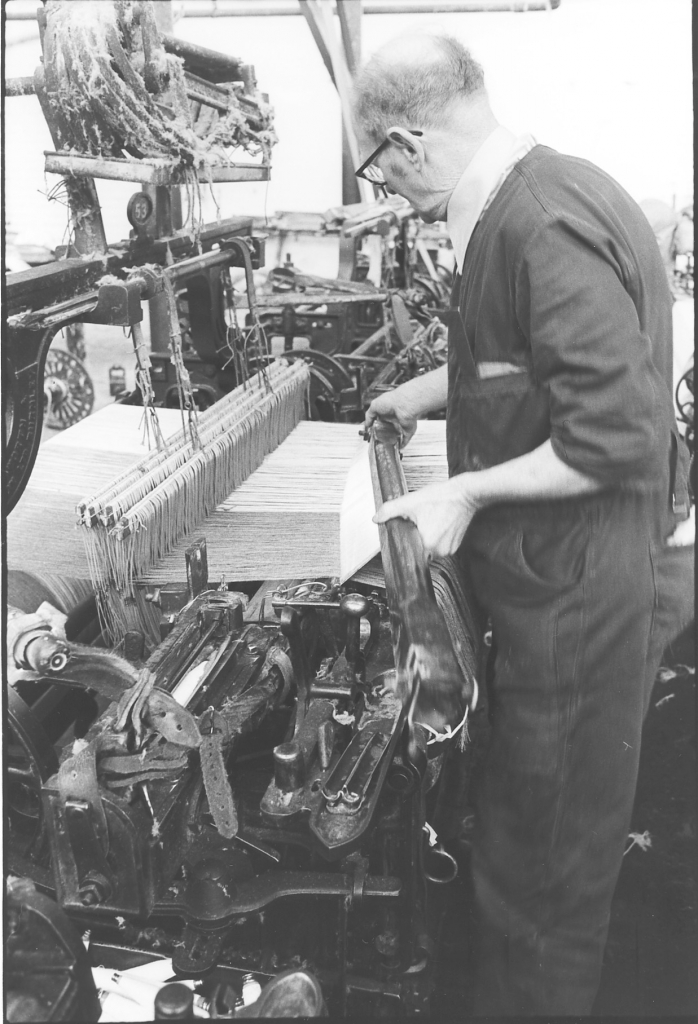

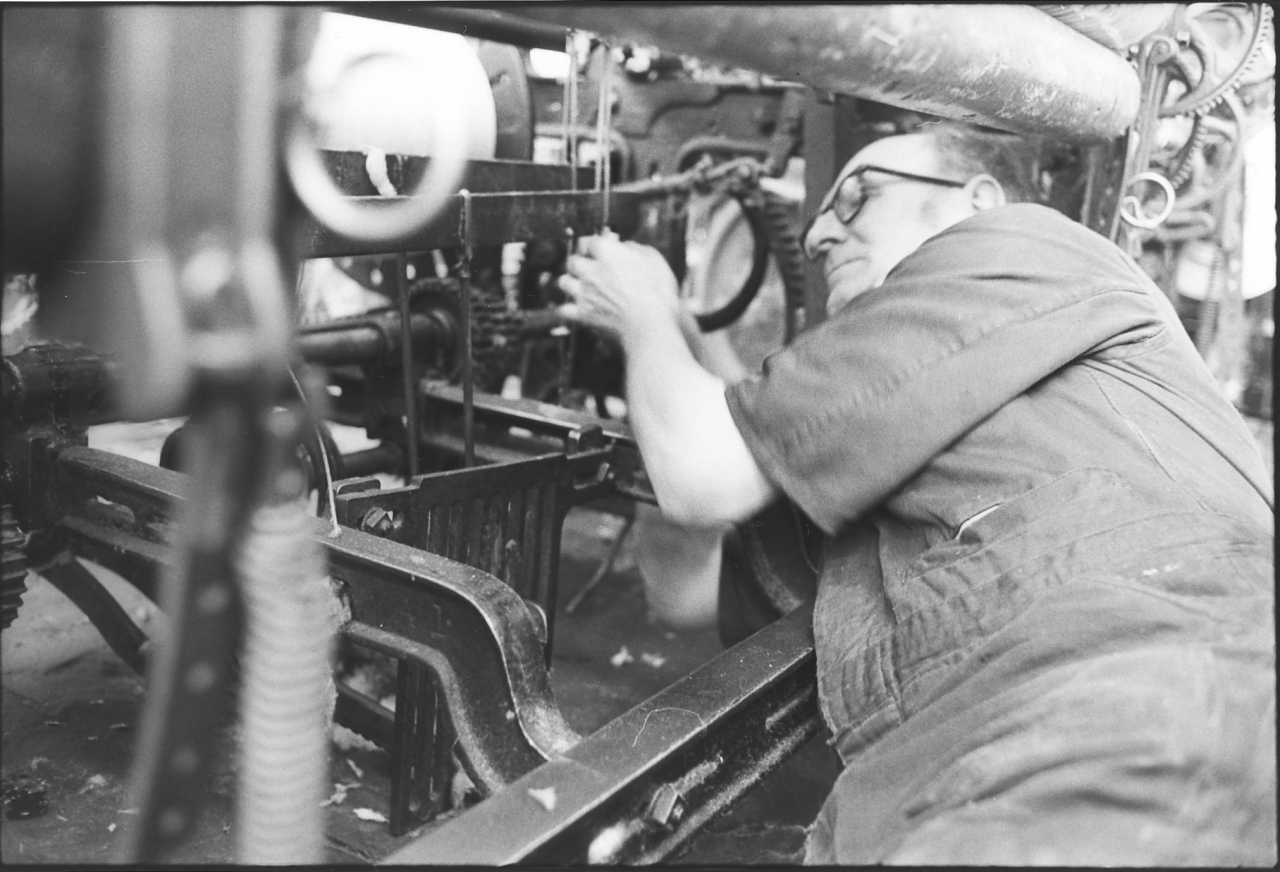

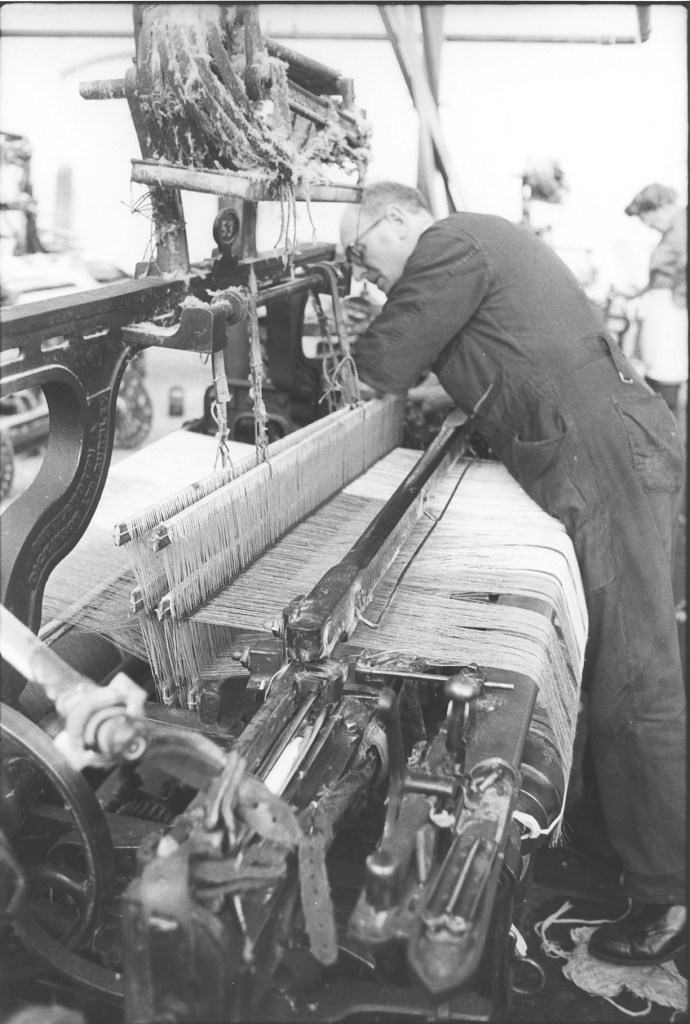

Ernie Roberts in 1979

[SIDE ONE]

Now then, Ernie Roberts, how old are you?

R-Sixty two. (1916)

Is that right! I didn’t know you were that old. Aye, where were you born Ernie?

R-Number 3, Hartley Street, Barnoldswick. [Bit of a problem here. There is no Hartley Street in Barlick and there never was one. I’ve checked with the Royal Mail and the only one they know of is in Earby. So, Ernie must have made a mistake. I think he means John Street but it may become clearer later on.] [In mid-June 2001 all this became clear. Hartley Street was the name of a row of houses on the left hand side of what is now Westgate/Colne Road about 100 yards above the entrance to Rocky Road/Cavendish Street. A bloke rang me up after seeing an article in the paper I wrote and he used to live there. He said they were numbered up to number 10 if his memory is correct. He also said that a Fred Taylor and his wife lived there with their son Anthony and Anthony’s grandmother lived next door.]

How many years did you live in that house?

R-Oh, as far as I can remember, happen about four years. And then we moved from there.

Where did you move to then.

R-Colne Road.

Still in Barlick?

R-Still in Barlick.

Can you remember why you made the move?

R-Oh, I fancy it were because t’family were growing and it were only a very little house.

What was your father’s name?

R-George Ireson Roberts

That’s an uncommon name.

R-It is.

Where were he born?

R-Gisburn.

And what did he do for a living, your father?

R-Weaver, they must have moved to Barlick, the Roberts family. His father, my grandfather, was a joiner working for whoever the estate was, you know, Gisburn Estate, Lord Ribblesdale I suppose. They moved to Bracewell first of all and me grandmother learned to be a midwife and then they moved up to Barlick. And then me father must have married me mother and my earliest recollection is of Hartley Street.

That’s it, and where was your mother born?

R-Brierfield.

What was her name?

R-Margaret Ellen Alton.

Yes, and how would your father get to meet her then, in Brierfield?

R-Oh, they’d moved to Barlick by then. This town must have been growing in those days , plenty of work you see. Plenty of work.

When your mother and father married, what year would that be, any idea?

R-Must have been about 1900, or may be later than that. Wait a minute, he went to the 1914 war as a young man I suppose, it would possibly be about 1900.

How many brothers and sisters did you have?

R-Oh say 11. My mother had two babies in ten months, that was a sign of the times, born and buried. But there were four of us survived, like three brothers and one sister survived.

So your mother’d be confined probably 11 times and only four survived?

R-Aye at least. But it were typical that.

Well, that’s the sort of thing that people today wouldn’t understand.

R-Well, it’s true.

I mean, that’s just incredible, what would you say yourself, I realise you weren’t there, but what would you say yourself was the reason for that heavy mortality?

R-Well, malnutrition I suppose, there were a lot of poverty you know. And I mean they’ve advanced a lot in medical knowledge. In them days it were just a matter of luck I suppose if you survived. Measles carried a lot off, diphtheria, scarlet fever, you never hear about these nowadays.

How long did the children that were born and died survive?

R-Well I don’t know really but these two children that me mother had in ten months lived to be a year and a year or and a half or so, then they both died in a fortnight wi’ German Measles.

So she had all the work with them and then they died. Aye, it’s terrible isn’t it. Where did you come in the family? You know, were you the oldest or the youngest?

R-Oh, I must have been about seventh or eighth.

Did any survive before you?

R-Just one brother before me and he’s still living.

When you were a child, can you remember any relations living with you?

R-No, I don’t think there’d be any room for relatives.

Did you ever have any lodgers?

R-No.

So when you were born, your father’s job ‘ud be…

R-Weaving.

And your mother would be weaving as well?

R-Yes. It’s possible they could have met in the mill you know. A lot of marriages were like….

Oh yes, I met my wife at work. Do you have any idea which mill they worked at in Barlick?

R-Not really, I’ve heard ‘em talk of Billycock. But I believe it would have been at Long Ing.

How old was your father when he died?

R- I think he were 32. He came out of the Great War badly smashed up and he died. Well, he died when I were five years old, that’d be 1921.

Did he work after he came out of the war?

R- No, he were disabled when he came out of the war.

Would he be on a pension?

R- I fancy so.

It wouldn’t be much though? [SCG’s grandmother received a pension of 26/3 per week for herself and three children in respect of the death of her husband in the 1914/18 war. Disability would have been less than this.]

R-Oh no.

Now, your mother, did she work outside the home after she was married?

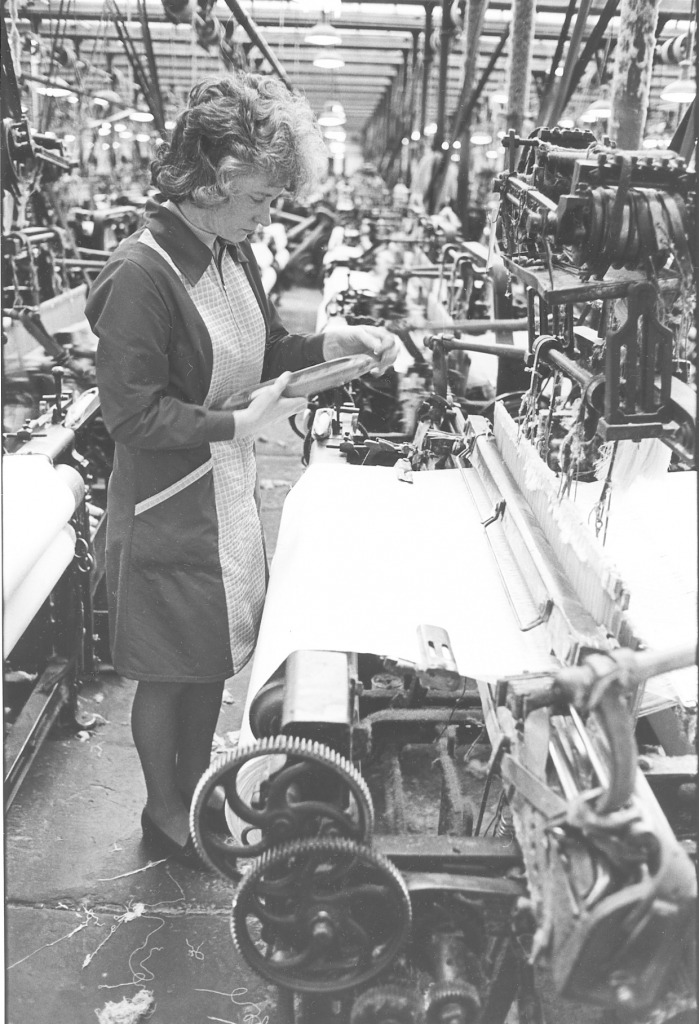

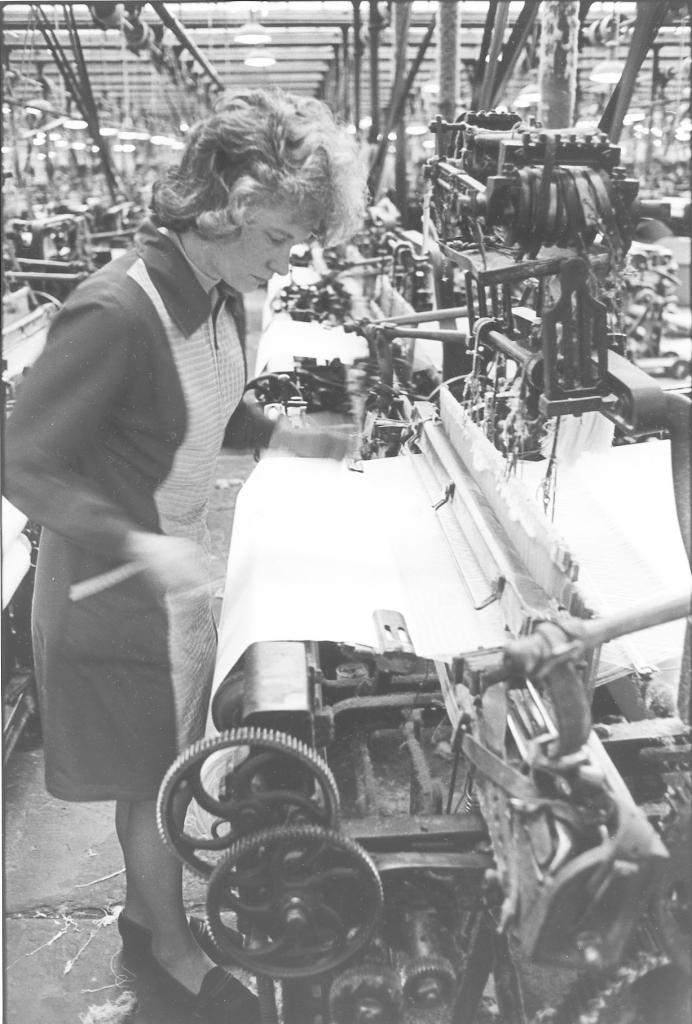

R-Oh aye, it were like a joint income that kept the place going, apart from being in the family way. I’ve heard me mother say that she’s taken a child out nursing, one walking by her side, she’s had a baby in her arms, carrying it, and one in her belly. And I’ve heard her say she’s known young women have a baby inside the mill, in a little basket.

Like take the babies with them?

R-Aye.

Yes, so that they could nurse them, they’d be breast feeding them.

R-That’s right.

And she’d be weaving?

R-Aye.

So what hours would she be working then?

R-Six o’clock in the morning ‘til six at night, up to Friday night and Saturday morning from six o’clock ‘til twelve. How many hours is that?

I can’t work it out straight away. [Standard hours pre-1919 was 55 ½ hours a week. This was reduced in 1919 to 48 hours. The Amalgamated Union census of wages in 1913 gave an average wage of 26/3 for a four loom weaver.]

R-There’d be breaks in between for dinner hour and breakfast.

What sort of a wage would she get for that?

R-Pound maybe.

How many looms?

R-Four looms, you had to be an exceptionally good weaver to have five looms in them days.

Four looms, aye. And if you had five looms you nearly always …..

R-Had a tenter, that’s right, aye.

Now there’s one thing, if you had a weaver’s help Ernie, who paid the weaver’s help, was it the weaver or the management?

R-Well, any pay ‘ud be from the weaver not the management.

That’s it, that’s something I’ve been trying to find out about.

R-And it’d only be coppers.

Yes. Well, Billy Brooks reckons that when he went to weave as a child, half time, he was paid….. I think he said it were…. No, when he went full time at first he was paid five shillings a week. [I was unclear of my facts at this time. Billy was weaving two looms when he got this wage. SCG.]

R-I’ve never heard of that, even in my day.

And sixpence for sweeping up.

R-It ‘ud be t’weaver who paid the sixpence, it wouldn’t be the boss.

Who looked after the children while she was working?

R-Well there were child minders. I had an aunt [who was a] child minder. She’d have about six or eight little uns to look after. I don’t know how much a week they paid like but it wouldn’t be much. And then most of the children went to school at three years old.

At three?

R-Aye, if you could get them in I suppose. I think I were three or four when I went into t’school.

That’d be to get you into school so they didn’t have to pay a child-minder.

R-That’s right.

So when that happened and you were going to school, between six o’clock in the morning and when you went to school you’d have to look after yourself. Between your mother going to work and you going to school.

R-That’s right. Well, th’oldest in the family used to be in charge.

That’s it. How old was your mother when she died?

R-Seventy three.

How old were you when she died? How long ago was that?

R-About ten years ago, 52 I’d be.

Did any of your family, your brothers or sisters, leave Barlick, you know, say before 1930. Did they leave Barlick to go and find work elsewhere, or did they all stay in the town.

R-No, they all stayed in the town.

Now, out of the houses you lived in as a child, which one do you remember best?

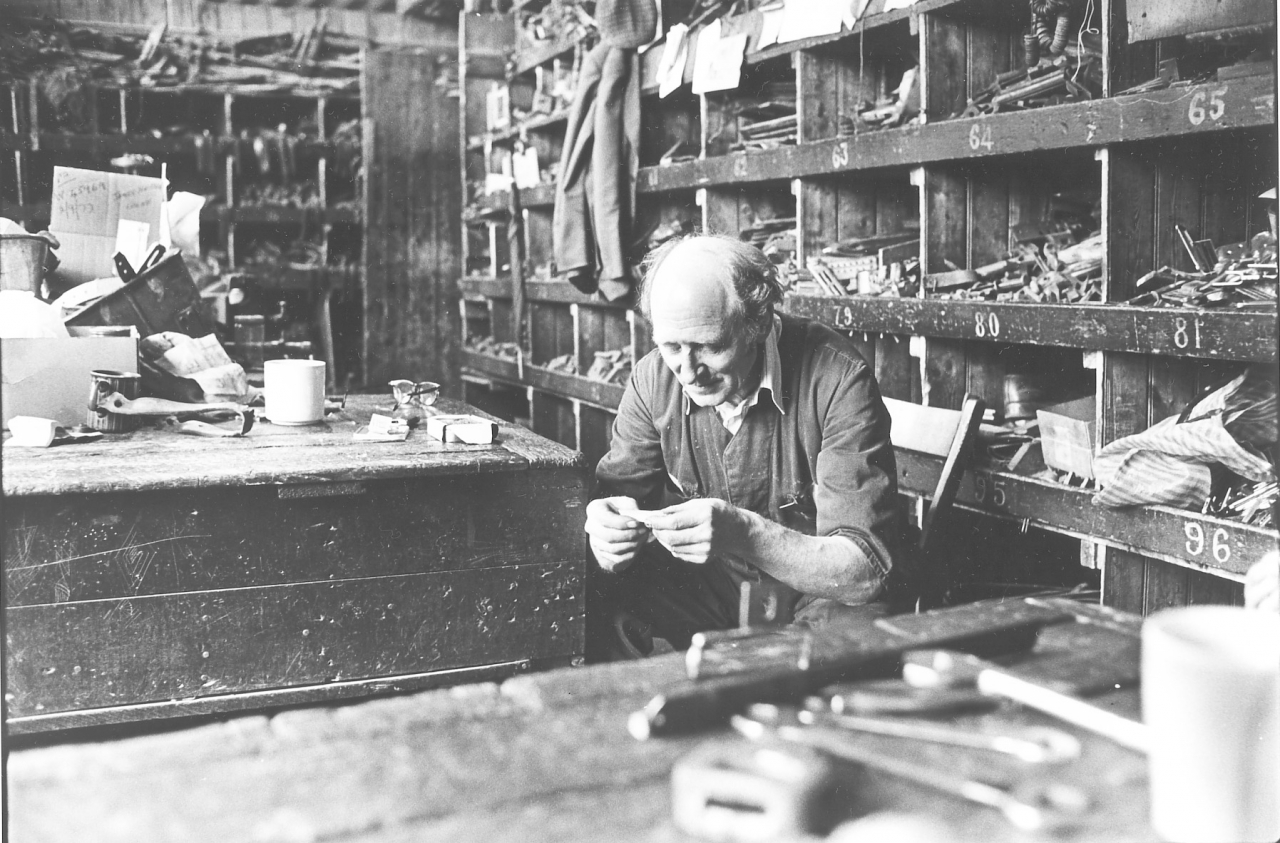

No 1 John Street in 1979.

R-Number 1 John Street, after me father had died. No money coming in, there were five of us living in this house, one up and one down, half a crown a week rent [2/6 or 12 ½ p.]. Me mother couldn’t go to work because she had a little baby and three besides. Our Wilson, when me father died he were only one year old, me sister was four or five, I was six and me elder brother [Fred] was ten.

And your father died in 1920?

R-Oh, it’d be what, 1922? Aye.

So you were living in 1 John Street in 1922 and it was half a crown a week rent.

R-And me mother had 25/- a week [£1-25p.] what did they call it then? Relief I suppose.

Parish?

R-Aye, Parish. She had that for a couple of years, really hard times they were. As young as I were at the time I can remember it as if it were yesterday, hard times. Gas goes out, no penny to put in’t meter. So they were, they were poverty days and not just us, it were general that. Twenty Five shillings a week for five of us.

How many bedrooms did the house have?

R-Just one bedroom. Two beds we had in one bedroom.

And what other rooms were there?

R-Just one up and one down, no other rooms.

So there’d be no kitchen?

No, no kitchen, just a sink and a gas stove next to each other.

Can you remember any of the furniture in the house?

R-Well, a square table in the centre and me mother’s pride and joy, a corner cupboard, always looked after that. And a wringing machine and a dolly tub and posser, and a dresser and horse hair sofa and a couple of chairs.

How about rugs, peg rugs?

R-Aye, I think we’d have a pegged rug.

Any lino?

R-Oh no, not at that time, later….

No, that’s it, later, when times get better. Well, one of the questions I usually ask is ‘If you had a parlour, can you remember what furniture there was in it.’, but it couldn’t apply to you because you didn’t have a parlour. Which room did you have your meals in Ernie?

R-The parlour, the place where the wringing machine is and the big square table and the pegged rug and sand on’t floor.

That’s it, sand on the floor.

R-I used to go to Mrs Yates on Church Street, A happorth of sand on pay day. [This was half an old penny, equivalent to about a fifth of a modern penny]

Yes, it’s where that ironmongers….

R-No, it were a greengrocer’s shop funny enough, you could always get a happorth of sand there. I know I remember one time Raymond Riding and me went in for the week’s happorth of sand and as we walked in Mrs Yates was bent over a tub of apples. ‘Eh, he says, you’ve got a rare arse Mrs Yates. So she stood up and said What did you say? He says happorth of sand please.

Your mother did the cooking?

R-Oh aye.

And the washing?

R-And the baking, she were a marvellous cook and baker, me mother. Marvellous.

Yes, she’d have to be.

R-Oh she had to be.

And of course you wouldn’t have a bathroom?

R-Oh no. And t’toilet were at least, well, you come on th’end of John Street and it were there. I don’t suppose you’ll ever remember Dick Jagger? Well, he walked up Wapping thirty yards, full length of a row of houses to t’toilet and that were a tub, it were emptied once a week.

Who emptied that?

R-T,Council. I think they called it ‘night soil’.

Yes, that’s the polite name for it because they sometimes used to empty them at night. They wouldn’t empty them at night in Barlick, no, there’d be nobody bothered in Barlick.

R-Oh no. In fact I once pulled the handle down. It always intrigued me, it had a handle up here and a little iron door in the bottom.

Oh, was this the cart?

R-The cart, aye. And if you pulled the handle down the little door opened and it bloody fascinated me for years. It come up one day and I thought Eh, shall I? And I did, there were shit running all the way down Wapping. I set off running and they used to scatter that disinfectant powder about you know.

So where did you have a bath?

R-Oh, we had a bath, a zinc bath.

Aye, a tin bath.

R-Aye we always had a bath, once a week in front of the fire and a small tooth comb, always a good combing.

Aye, a nit comb.

R-Mine were red uns! I had red hair in them days.

And did you have a special bath night?

R-Friday night.

Aye, it always used to be Friday night. Did the house have piped water?

R-Oh yes, just cold.

One cold water tap downstairs.

R-Usually dripping!

How about stair carpet?

R-Are you joking? You can’t nail bloody carpet to stone, they were stone steps.

Do you think any of the neighbours had a stair carpet?

R-No, only t’landlord, he lived on the same row. Bloke called Lund. Mother used to call him ‘Monkey Lund’ I mean we were a set of buggers, we must have been, she got her notice to quit about once a week.

What do you think that were for? Down wi’ the rent?

R-Oh I don’t know. I think she always paid the rent. No I think we were mischievous you know.

How about curtains?

R-Oh, they’d be a bit of mill cotton dipped in a Fairy Dye, not a Fairy dye in them days but you could get Dolly blue and Dolly yellow. Well, they could have either blue or yellow curtains, yard or two of mill cotton, they’d have been, you know, skived. [A bad piece of cloth that had been cut out of a piece. This is different than a fent which was the cloth end cut off the piece.]

Aye, that’s it, can you remember [is that] what the neighbours had?

R-Oh most of them, aye, most of them.

That’s it, and can you remember any of the families not having curtains?

R-No, I don’t think I can. They’d all have a bit of a curtain up, I mean, they need a bit of privacy occasionally, don’t they.

Yes, did your mother use to donkey stone the doorstep?

R-Yes.

And that’d be fairly general?

R-Oh aye. They were a halfpenny apiece, you could have hard or soft. There were an old lass lived further up the street, called me in one time. Want to go to for a donkey stone, a soft un? They were a halfpenny. I’d been before and she gave me a halfpenny for going. So, she’d give me a halfpenny and I had to go for this donkey stone, I came back with it and no halfpenny for me. So I walked away and got to th’end of the street and I thought She’s forgotten. So I went back and knocked on’t door and she came to the door. Was that donkey stone a soft un or a hard un? I think we called her Mrs Parkinson. Eh, she says, I’m forgetting to give you a halfpenny lad, I am sorry. So she gave me a halfpenny. I were a crafty little bugger even in them days!

You must have been. Was the house gas lit?

R-Gas.

What sort of jets were they, mantles?

R-Mantles, oh yes. In summer you used to keep the door closed for chance a buzzer ‘ud come in and off went the mantle. I’ve always been a reader, me. I used to raise coppers for the Wizard, the Hotspur, oh reading, I used to love it and I still do.

When can you remember first having electric light? Did you ever have it at John Street?

R-Never.

How about household rubbish, it’d mostly get burned on the fire…

R-Dustbin, outside.

Were it outside the house or near the toilets?

R-Outside th’house.

How did your mother do the washing?

R-In’t sink and dolly tub and we had a rack, that were another part of the furniture, you used to hoist it up and down on a pulley. That were a luxury. I mean most people had a line or a piece of rope or string. What washing we had, we didn’t have that much washing you know, it were one shirt and happen one of these and two of that if you were lucky.

How often did your mother do the washing?

R-Oh, every week I fancy.

How long did it take her, any idea?

R-Oh, it must have taken her two or three hours and then she’d to get them dried and ironed.

How did she dry it, a line outside?

R-A line across the street.

How about ironing, did she iron?

R-She ironed on the big square table.

What sort of an iron was it?

R-It used to be a box iron, she used to get these little metal things red hot and put them inside the iron. Have you ever seen one of them?

Yes, like a cast iron block that went inside. But there were such things as gas irons weren’t there?

R-Oh aye.

And you’d be at home sometimes on washing day, what can you remember most clearly about washing day?

R-Well, whoever were available had to turn the wringer you see. I remember one particular day, in a hurry, wanting to go and play out, but I had to wind. So I’m winding like hell, you know, full speed, top gear, and it must have been a sheet going through and like it got to the end and I’m still winding like hell and it shot out. The handle slipped out of me fingers and it whizzed round and caught me right in between the legs, I don’t think I’ve been right since!

How did your mother clean the house?

R-Brush. I don’t suppose it took a lot of cleaning really, used to change the sand once a week, you didn’t bother about rugs.

Was there anything that she paid special attention to, something she really thought a lot about?

R-Only the corner cupboard.

Why do you think she thought such a lot about that?

R-Well I think she set up with that when she got married at first and most money she ever had in her life, she used to tell this story many a time. Before the family started growing up, may be she’d had one baby you know. She saved six half sovereigns in this corner cupboard. Her and me father went out for a drink one night and when they came back they’d had a burglar and these six half sovereigns were gone. She never got over that.

I should think not. And did you and the brothers and sisters have any jobs to do round the house, you know, regular jobs.

R-Oh aye, especially when our Wilson, the youngest, started school and me mother started work then weaving, and then we all had jobs. Fred, th’eldest brother he were always a milk lad, I were a lather boy. I don’t remember me sister ever having a job but I were a lather boy, I couldn’t have been very old, eight or nine maybe at the most.

That’d be at the barbers, lathering blokes up for a shave.

R-Aye, a bloke called Demeline. [Billy Demeline]

How about jobs round the house?

R-Well aye, a bit of washing up I suppose.

You’d all have to muck in.

R-Light the fire, oh aye. But when me mother started weaving I used to have an aunt come and she was paid half a crown a week to clean up.

Did the older children help the younger ones with dressing and eating, they’d have to help each other out?

R-Oh aye.

Did your father do any work in the house?

R-Oh no, he were buggered. He were just…. Well he managed to get a baby but otherwise he were badly smashed up. I’d forgot, after me father had been dead two or three years she’d made enquiries and they’d gone into me father’s war record and she finally got a war widows pension so things bucked up after that.

How much were that then, can you remember?

R-Oh, it’d be at least two pound a week. Well, that were a little fortune. She had a pension for herself and the three of us but t’youngest didn’t qualify for some reason. She’d have two pound odd a week.

And it was a rented house.

R-Oh aye, we’re still at number 1 John Street, half a crown a week.

How about the landlord, were he a good landlord?

R-Oh no, I think he were a Methodist, he weren’t a good landlord. They did say he bought all those seven houses for £300, the whole row. A bit of a sanctimonious fellow he was.

Did your mother ever do anything in the house when she wasn’t weaving. Did she ever do anything to earn an extra bit of money?

R-Oh no.

Do you remember anyone in the neighbourhood doing anything like that, any work at home, just to earn a bit more?

R-Well, what sort of work would they do?

Well, things like taking in washing or child minding.

R-Oh aye, they used to do that but not in my house. Oh plenty of that went on, taking in washing and child minding.

That house is still standing?

R-Yes, it’s a residential area now is John Street.

You mentioned that at one time you were on the Parish. How much a week was that?

R-Well, she drew 25/-.

Where did she get that 25/-?

R-It were fetched to the house every Saturday morning, 25/-, and the relief man finally got summonsed for robbing old folks and widows. Me mother should have been getting 35/- a week all that time. That ten bob a week would have made all the difference to her and us. But this bloody thief got fat robbing these poor people. They called him Harrison.

How long was that going on for?

R-Well it must have been going on for quite a while. He got nine months in the second division, whatever that is. I bet he’d have, what do you call them that tickle your palm? Freemason.

Ah yes, but actually I think second division was without hard labour. First division was with hard labour and second was without. I think that’s right.

R-Possibly it were. But that were his punishment, but he punished me mother and us and lots of people besides. Because in them days you know, they only had ten bob a week and that were their lot, I mean the old age pensioners.

Yes, what age did you draw the pension then? Do you remember?

R-No.

It don’t matter. Now then, back to the house, your mother cooking, what did she cook on?

R-On a gas stove. A rented gas stove. About five bob a year they were, rented from the Council. A solid job that used to sit there and take any amount of bloody punishment!

It weren’t black leaded were it?

R-I think it might have been, aye, black leaded.

Aye, I think parts of them would have been black leaded. Did she make her own bread?

R-Yes.

How much did she do at a time?

R-Depended how much brass she had I suppose, but I’ve seen her bake ten pounds of flour at a time. Aye, cakes, bread and all sorts, sad cakes, sometimes a custard, lovely they were.

Aye, that’d be like a weeks baking. And what kind of cakes did she bake?

R-Caraway seed cake, rice and currant pies, apple pies, blackberry pies when they were in season, any sort of pie. We were fetched up on rabbit pies as well.

Where did you get your rabbits?

R-Oh there were millions of rabbits round here, millions.

Who caught them?

R-My brother Fred, but I had an uncle that were a good man at it as well. Me uncle Ernest, the chap I’m named after.

Did your mother make Jam?

R-No, I don’t think she could make jam, she used to make lemon curd, that’s delicious. Sometimes I sit back and think I wonder how they made it. I know there were eggs in it, eggs were only …. You’d get a baker’s dozen for a shilling you know, if you had a shilling. [A ‘Baker’s Dozen’ was 13. SCG.]

Aye, if you had a shilling. Did she make pickles?

R-No.

[SIDE TWO]

Did your mother ever make any home made medicine?

R-No. She used to take medicine every night, all the years I knew her. A pennyworth of Beecham’s Pills, you used to get a screw of them for a penny. [Beecham’s pills were sold in a little twist of paper. I think there were about 6 in a twist. SCG.]

Yes, that’s it, every night. And what did you usually have for breakfast?

R-Oh I don’t know, it varied I suppose. If we were lucky we’d have a boiled egg. Oh, but one thing she could make, a thousand sandwiches with one boiled egg, egg butties. She used to soft boil it and dip the knife in, marvellous she were.

How about Sunday dinner, did you do better then?

R-Well, it’d be rabbit pie. These are hard times I’m talking about, before things bucked up a bit. But one thing about me mother, when she did get her war widows pension and we were better off, we used to live like fighting cocks, roast beef on a Sunday, Yorkshire pudding and nice vegetables.

What would you usually have for your dinner during the week?

R-Well, it’d be catch as catch can wouldn’t it? Oh, there used to be a café, you could get torpedo and peas for three pence and it used to be a standing order when things bucked up a bit.

What were that fellers name, whereabouts were that, on Wapping?

R-No, on Lamb Hill, bottom of Manchester Road, Holmes’s café. It used to be full of kids at dinnertime, pie and peas for three pence and me mother used to pay at weekend.

I’m not sure if Newton hasn’t told me about being sent out there on an outside job by his father, his grate had fallen out of his oven. How about tea, at tea time?

R-Oh well, there used to be a bloke called Bob Hudson came round with fish you know. Kippers were only tuppence a pair so we could have half a kipper apiece for tea. And cockles and mussels. Eh, I mean, every day wi’out fail, Bob’d come round and he used to have fifty or sixty cats trailing him ‘cause he used to gut these fish and chop ‘em up a bit and chuck his debris in a bucket hanging on the back of the cart. Cats used to sneak up and put a paw in and grab a bit.

How would them come into the town do you think. By train? Coming in on the railway?

R-The fish? Oh aye, everything come in on the railway, everything came in and out.

When you went to bed, did you ever have any supper?

R-Aye I fancy so but I can’t remember really.

Did you have a garden or an allotment?

R-Are you joking?

I’m joking! So you never kept any animals at all.

R-Oh, we always had a dog. Aye, Old Jack. He seemed to last as long as….. t’poor old lad got killed eventually but he were a good rabbiter.

How about your Sunday dinner, how about puddings, did you manage a pudding?

R-Oh aye, rice pudding, sago pudding, rhubarb pie, apple pie and custard of course.

How much milk did your mother get a day, any idea?

R-No, no idea. A pint a day may be, it were fairly cheap then.

How was it delivered?

R-It were delivered the old fashioned way, in a can and t’milk lad poured the milk into whatever you had available, a jam jar or a jug if you were lucky.

Aye, a lading tin. How about butter, margarine and dripping?

R-We always had butter and dripping, never margarine. For some reason me mother seemed to think it were some concoction, it’d poison us all.

She could have possibly been right! How about fruit?

R-Fruit? Oh well in them days Savage used to sell out Saturday night, about ten or eleven o’clock at night. You could get a bunch of bananas for a tanner. Happen 30. Bags of apples, everything were very cheap, he used to sell all his fish and fruit off because there was no refrigerators. Oh, there could have been couldn’t there?

So, he’s aiming for a clearance on a Saturday night.

R-He used to sell out every Saturday night. So I fancy th’old girl used to get fruit there but I think it might have been a bit of a luxury because I don’t remember a banana.

Well, I’ve a list of foods here, you tell me how often you used to have them, I’ll list em, shout out, banana is the first one.

R-luxury.

Rabbit?

R-Oh regular.

Fried food?

R-Well, bacon and egg.

Fish.

R-Kippers and cod fish.

Cheese?

R-I don’t remember any cheese.

Cow heel, tripe, trotters, black puddings?

R-Oh plenty, yes, all that.

Eggs?

R-Aye.

Tomatoes?

R-Yes, tomatoes in season but I don’t think they were as common then as they are now because every bugger grows ‘em now.

Grapefruit?

R-Oh no.

Sheep’s head?

R-Sheep’s head yes. They are very tasty a sheep’s head. She used to make broth with sheep’s head in, bones and all.

That’s not down on the list here but I’ve seen us go out and get bones for the dog and boil it for broth first and then give the bones to the dog.

R-Oh aye, you could make a meal very cheaply you know. A penny onion, two or three potatoes for a penny, half a pound of pie bits for about threepence, that’s only fivepence, and a pinch of salt.

Yes, and you start with a good stew.

R-Aye, I’ll tell you what we used to do when we were kids. It sounds a bit cruel nowadays but this Ernest I mentioned before [his uncle] he used to trap starlings in winter and we used to skin ‘em and hang ‘em on the top bar and spit ‘em and keep turning ‘em round until they were cooked.

When you say ‘top bar’ you mean over the fire?

R-That’s right. Hang ‘em there on a piece of string and keep turning ‘em round and they are good, tasty with plenty of fat on them and we used to eat them regular.

Bones and all?

R-Oh I wouldn’t say bones and all.

Can you remember if your mother ever bought much tinned stuff?

R-No.

What vegetables did you eat most often?

R-Well, It’d be the cheapest vegetable, cabbage. But I think we were, for a long time I think, we were deficient of some diet, some diet you know. We didn’t get a balanced diet like it is today. I mean, you can see the difference in the young uns today and when I was young. I’m bow-legged, and it were common in those days for kids to be bow-legged.

And do you think that’s what caused it?

R-I think so, a stodgy diet, not enough vegetables and fruit.

Well, rickets used to cause bow legs didn’t it. So do you think you had it, just a mild case you know?

R-Aye. Oh I think I might, I might have had. From all accounts, when I were really young I were on half a dozen death beds in no time. Aye, it’s true that, so they tell me.

So you can’t remember much about tinned food, have you any idea why your mother wouldn’t have it?

R-Well, it must have been an expensive way of living then, like it is now.

Yes, quite. How about family drink? Tea, coffee, cocoa?

R-Tea, we always liked tea.

No coffee or cocoa?

R-No.

How about Christmas dinner, what can you remember about that?

R-Christmas dinner, well, we once had a turkey and I collected it at Savages and it were a big un. I were walking up Wapping wi’ it over me shoulder and its head were trailing on the floor. I must have been about eight happen. Th’old girl had raised the wind somehow I suppose but we had turkey that year.

That’d be about 1924?

R-It could be, aye.

Any idea how much it cost then, the turkey?

R-Oh no, no idea.

What was your favourite food when you were that age?

R-I don’t think I had a favourite food.

No, you’d be hungry all the time. That’s it, sense in that. If you had a really bad week and your mother were hard up, really hard up one week….

R-on her chin strap.

Aye, that’s it. What would you get to eat that week. When things got down to rock bottom, what was the main thing you ate then?

R-Oh, it’d be nothing happen. I remember me mother coming up to school at play time. They used to lock the gates then at Church School. And I remember her pushing a banana through t’bars for me, I hadn’t had any breakfast so she must have been desperate that day.

When you say ‘Church School’ do you mean York Street CofE?

R-Oh yes, well all the family did.

How about people that were working, they wouldn’t come home for their meals would they? They’d take ‘em to the mill wi’ ‘em.

R-Aye, we used to have a can you know.

Brew can?

R-Brew can and bait tin.

What would they generally take? Sandwiches or something to warm up?

R-Aye it’d be sandwiches, bread and jam, tomato, bananas, potted meat happen.

When your mother went back to the mill and you were at home did you ever take food into the mill for her?

R-No. But I used to come up to this mill [Bancroft] with a can of tea for me aunt Louise. That were afore me mother started work, when me younger brother were really young you know. Happen about one or two year old, and I used to come up here wi’ a can of tea for me aunt Louise.

Why was that? Why did you bring a can of tea for her, why didn’t she brew it here?

R-I don’t know. I don’t think they’d be allowed to brew it here.

Is that right?

R-And then, I think they’d only have steam at certain times, meal time and they used to pay a penny a week you know.

Aye, for brewing tea, for use of the boiling water.

R-Aye, it’s a bloody good job they didn’t sell blood in those days or they’d have been giving a pint of blood a week, besides t’favour.

Can you remember your mother going short to make sure that you had something?

R-Oh I’m certain she did, certain. I mean, I remember her in those days, she were like a bloody skinned rabbit. I don’t think she were above six stone or seven at the outside, and had all them children, she must have gone short.

How old would she be, say in 1925?

R-Thirty?

Thirty, aye, that’d be about right.

R-She were married young you see, she’d had eleven children, one every year, two in one year, she’d two in ten months.

Who usually did the shopping?

R-Well, it were a pennorth of this and a pennorth of that. There were a shop, just opposite our house, Matthews shop, grocers. I mean there were penny packets of tea, penny onion, pennorth of taties, I mean, who does t’shopping?

Vegetables. Where did you get them?

R-Well it’d be Savages I suppose, or Mrs Yates, You could buy cut apples and oranges, you get a good do for a penny. You know, same as apples half rotten, cut off.

That’s it, they still do it. He [Jack Savage] still does it.

R-I suppose they do, aye.

Savages, you can still go into Savages and get you know, a little bag of vegetables for a stew.

R-That’s right. Broth bits they call ‘em.

And a lot of that’s like good bits cut out of the old uns. There’s nothing wrong wi’ it, nothing wrong wi’ it.

R-Oh no.

Where would your mother get her meat when she could afford meat?

R-Ah, Tomlinson, he had a butcher’s shop on Church Street, Jack Tomlinson. He were very good with me mother. He used to slip her a bit, you know, I mean a bit of meat!

Did your mother shop at the Co-op?

R-No, only the wealthy shopped at the Co-op in them days. Share holders, I mean I think it were £2 to be a member.

Yes, but surely you could shop at the Co-op if you weren’t a member?

R-Oh yes, certainly you could but I never remember me mother going to the Co-op.

Aye, that’s interesting. Was there a market in Barlick in them days?

R-There were an open market down t’Butts. We used to go there for bargains. And then there were t’Majestic Ballroom, that were a market about twice a week, maybe once a week, Thursdays. No, now I come to think about it it were permanent because when me mother got a pension she got some back pay and she took me in there and she bought me a scooter. I wouldn’t be so old then and it were a flag floor and there were a market inspector catching me be the scruff of me neck and he were going to chuck me out for riding this scooter. I said ‘Me mother’s just bought it’ so he let me off.

Do you think there was much difference in the prices between the local shop at the corner of John Street and those in the middle of the town?

R-Oh I don’t know, I shouldn’t think so. I mean supermarkets were unheard of in those days, price wars and cut prices. There’d be a bit of difference.

How about credit, would there be any chance? Would they give credit at the corner shop?

R-Oh yes. It were regular were credit. Yes, everyone had a shop book. I mean that’s how grocers got to be so well off, sneaking odd little items in.

How about pawnshops?

R-Oh marvellous pawnshops! Do you know, it’s my ambition to be a pawnbroker, it is. I’ve always said if I win a lot of money on t’pools, I’ll be a pawnbroker. They’re salvation, it’s a religion to me is pawnbroking. I mean they do a real service. If there were a pawnbrokers shop in Barlick and I were hard up but had some article I could raise a shilling or two on I’d go there rather than ask anyone to lend me. I’ve been in t’pawnbrokers hundreds of bloody times.

That’d be Jimmy Wraw’s in Barlick wouldn’t it.

R-Yes it were.

Was there just one in Barlick or more than one?

R-No, just one.

Aye, and did your mother use the pawnshop?

R-Regular. I had a…. when I got about 14 or 15 I had a pin-striped suit and the bloody thing were more often in the pawnshop than out. In at Monday, out at Friday, I think Friday must have been payday.

Aye, I’ve heard it said that some people actually thought that one of the beauties about pawnbroking was that their clothes were actually better off and they were out of the way at the pawnbrokers than they were at home. People then hadn’t got wardrobes. [In later years I found that there was a similar situation in New York. People would take their winter clothes in to the dry cleaner in Spring and leave them there all summer to save on space in their apartments. They did the same thing in Autumn with their summer clothes.]

R-well, that’s a good idea, I fancy it is so. They used to wrap them up and there were plenty of moth balls about. [Moths were a big problem in those days because houses were damper and they could breed in anything made of wool. The grubs ate the wool and this is the origin of the term ‘moth-eaten’. The defence was moth balls, or more often moth rings, shaped like a small ring [Trade name for the rings was Mothaks] . One of these would be hung on a piece of string on the clothes hanger. They were made of camphor and would keep moths away from the clothes. This was true until central heating became common in the mid 20th century.]

Yes, if you had a good suit it were better looked after at Jimmy Wraw’s than it were at home. So you think there’d be good business in the pawnshops then?

R-Aye, they did good business. And if you wanted to buy a secondhand coat or owt you could go and buy a forfeited pledge they called it. You put an article in, I think it were a halfpenny a month for two bob value, over twelve months. Then you could redeem that loan, if you didn’t redeem it you lost the article. It were really high interest to pay but it were convenient.

Yes, but it was always there, it was convenient. Would you say that the pawnshop was fair?

R-Yes, especially wi’ a bloke like that. What did they call him, can you remember, him with the bald head?

I can remember him but I don’t know his name.

R-Aye, I’ve forgotten his name but he were a grand chap.

And they’d be widely used. Would you think that other people looked on them in the same light?

R-You mean the better off people?

Well, the high society, how would they regard them?

R-Oh I reckon they’d look down on them. They might call it a den of iniquity. I did hear a story one time, they reckon there were a young woman went into Wraw’s one time and she said to this pawnbroker, ‘Do you take anything?’ He says ‘Yes’. So she says ,’Will you give me five shillings on this until I gets me insurance?’ and she put her belly on the counter, she were eight months gone! And he might have given her the five bob.

Aye, possibly, he were a decent bloke. Can you ever remember anyone lending money?

R-Do you mean man to man?

Well, not necessarily, no. Somebody that regularly, someone in the neighbourhood that you could go to if you were really hard up and borrow off ‘em?

R-You mean a money lender? No. Not in my experience.

How about Provident cheques and things like that.

R-Oh yes, aye, Provident cheques, I think most people had Provident cheques.

Did your mother ever have them?

R-Oh I think she did. I know a Scotchman used to come, they used to call them Scotchmen, these trading men you know.

Aye, what was the other…. Tallyman wasn’t it, Tallyman.

R-Tallyman.

They wouldn’t have just as good a name as pawnbrokers would they? Because it were fairly high interest for what you got.

R-Aye.

Were there anything that you used to eat when you were young that you can’t get now? Can you think of anything?

R-Well, rice and currant pie. I haven’t had that since I were young.

No, it isn’t often made now. And rabbit, there isn’t a lot of rabbit about now is there?

R-Well, I don’t fancy rabbit now, not after myxomatosis job, another invention of the bloody devil. Myxomatosis, terrible, an invented disease just for money, t’profit job, they were eating farmer’s grass.

Now you were born in 1916. so you’ll not remember the First World War. Can you remember ever having to queue though?

R-No.

Things were improving then.

R-Aye, by the time I realised what a queue was.

Did your mother ever make any of your clothes?

R-Oh never. I used to dread her darning me bloody stockings!

Is that right?

R-Oh she were the worst darner and sewer in the world but the best cook. She couldn’t stitch a button on, not right I don’t think.

Aye, that’s funny that isn’t it. How about passed on clothes?

R-Oh aye, they were mostly hand me downs. Jumble sales you know, in them days they were very popular. In fact you couldn’t get in unless you were early. I used to love going to jumble sales even when I were growing up, youth and manhood. I used to go looking for bloody antiques you know, but everybody’s been educated since them days , there’s bugger all now, only worn out hand me downs.

If your mother bought any clothes [for herself] where would she usually buy them.

R-I don’t remember her ever buying any. She had a few sisters and they used to hand them down. I don’t think I ever saw me mother dressed up in all me life. Not really dressed up, fancy hat on and all you know.

What happened to your old clothes, if you had any?

R-Well, t’rag chap used to come round and you’d get a donkey stone for ‘em. But mind you, they’d be old. There’d be t’breeches arse out of those we’re talking about.

What did you wear for school?

R-Well, what did you wear for school, you wore what you wore every other day, Sunday included.

Aye, apart from the pin stripe suit.

R-Oh well, that were in later days when things bucked up. I remember running round Barlick wi’ me breeches arse out singing ‘Vote vote vote for Dicky Roundell’ Well, I didn’t find out for years he were a bloody Tory, I didn’t know any different.

And it’d be clogs of course?

R-If you were lucky. Oh, I can tell you a little story about clogs. There were a manufacturer in Barlick called Slater, he used to run t’Clough. He must have been sympathetic towards me and me elder brother, we had an old pair of shoes on I suppose, or broken clogs or something. There were a clogger shop at bottom of Manchester Road and he took us in there one Saturday morning and he said to t’clogger, Barlow they called t’clogger. Barlow, make these two lads a pair of clogs apiece, today. And I sat there all Saturday and he made these clogs and Slater left instructions with Barlow to tell us that when a clog iron broke we were to go in there and have it mended. Now in my mind he were a saint, I mean, taking pity on two poor lads like that.

Do you think he did that for anyone else?

R-I never heard of it. And that chap used to slip me sixpence many a time. He’s even taken me to Yates, greengrocer’s shop and picked me a nice apple out. I remember that fellow as if it were yesterday, he were one of the ugliest fellows, facially ugly, I’ve ever seen in me life but he were a gentleman.

Do you think your mother ever worked at Clough?

R-Maybe when she was a girl.

How about a hat, did you wear a hat in those days?

R-Shawl.

You wore a shawl?

R-No, not me, Oh do you mean did I wear a hat? Oh no, I might have had a cap, aye.

Now, well I like caps.

R-I’d look bloody well wi’ a shawl on! Yes, I had a cap, they were only a shilling at Atkinson’s it had this fancy badge on the front, I remember it, I fancy that’d last me a long time.

And of course, you’d have your pin stripe suit for Sunday best.

R-Oh aye.

What did your mother wear for housework?

R-She wore for housework what she wore for everything else.

That’s it but she’d wear a pinny wouldn’t she?

R-Oh aye.

Were it a pinny or a fent?

R-No, it’d be a pinny I think.

But she’d take that off before she went out wouldn’t she? I know me mother used to be the same, she didn’t want to be seen out of the house wi’ a pinny on. Always struck me did that. I’ve a question here, how many outfits did you have at any one time?

R-An outfit! Bloody puncture outfit happen. How many outfits….. Oh.

When you were all at home did you all sit down for your meals together?

R-Yes, well, I don’t think there were room for everyone to sit down together., first there is first served.

Yes, but everyone had a meal at the same time?

R-I think there’d be one or two standing but we all had a meal at the same time, yes.

Was your mother strict about behaviour at the table?

R-Oh yes, very strict. I remember her throwing a loaf at Wilson, he ducked and it caught me reight in’t nose and there were blood on the ceiling. Oh, she were a bugger for discipline.

So she’d be fairly hard on you for like times you came in at night?

R-Well, she weren’t very strict, not that way but she was strict in others. I remember one time, I’d happen be about seven or eight, swimming in Calf Hall dam, naked. Someone told me mother. Well, I were like delicate, I weren’t supposed to go swimming or get witchered [getting wet feet] or acting the goat in that way. She came up there, dragged me out of the dam and made me walk home naked from Calf Hall dam to John Street and every few strides she’d whack me arse wi’ a picking band. Aye, memories…..

Can you remember anyone saying grace before a meal?

R-Oh no.

Prayers at home?

R-No, never.

When you went to bed?

R-No.

If you had a birthday was it any different than any other day?

R-No.

Presents?

R-Christmas we used to get a bit of sommat, an orange or an apple. Oh, I remember one time at Christmas, Salvation Army came, we had all gone to bed, the five of us, nothing in the house and the Salvation Army came and banged on t’door and me mother got up, we’d a basket of Christmas fare. I think they’re my favourite religion, the Sally Army. If you remember during the war, the Salvation Army were always there, and even today, if there’s a disaster, they are always there, any part of the world.

Can you remember Easter?

R-Easter eggs. But they were home made Easter eggs, hard boiled. Coffee comes into this. If you put some coffee in a pan and boil a white egg you get a beautiful brown egg and then we used to go out rolling ‘em.

Was there any musical instruments in the house?

R-We were always musical, tin whistles, mouth organ, we had a piano, an organ, when things bucked up. Early days when we started work, me and Wilson, me younger brother, bought a piano and organ for ten bob and we didn’t half give them some hammer for a week or two and we came home from work one night and she’d given them to t’rag chap!

How about a Jew’s harp?

R-Oh aye, a Jew’s harp as well.

When you were a kid, did you ever make bones?

R-Oh aye, bones and knocking spoons as well.

Aye, pieces of slate. That’s it, so you’d have sing songs then?

R-Oh I fancy we would. Aye we used to have sing songs. Me mother were always whistling and singing and I’m a whistler, I’m always whistling.

SCG/26 May 2001

8812 words

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 78/AC/2

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE JUNE 22 1978 AT BANCROFT ENGINE HOUSE, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS ERNIE ROBERTS, TACKLER, AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Now then Ernie, I just want to start with one or two things that cropped up off last weeks tapes. Have you remembered where the house on Colne Road was?

R-Aye, No. 9, Westgate, that were a decent house.

When you say ‘decent house’, what do you mean?

R-Well, a decent house, better standard than No. 1 John Street, two bedrooms and kitchen and sitting room and a back door and a yard.

When did you move there?

R-Oh, I’d be about 15.

So, you were born in 1916, that ud be about 1931, you’d be working by then.

R-Oh yes, things had bucked up by this time. Two workers in th’house, me and Fred.

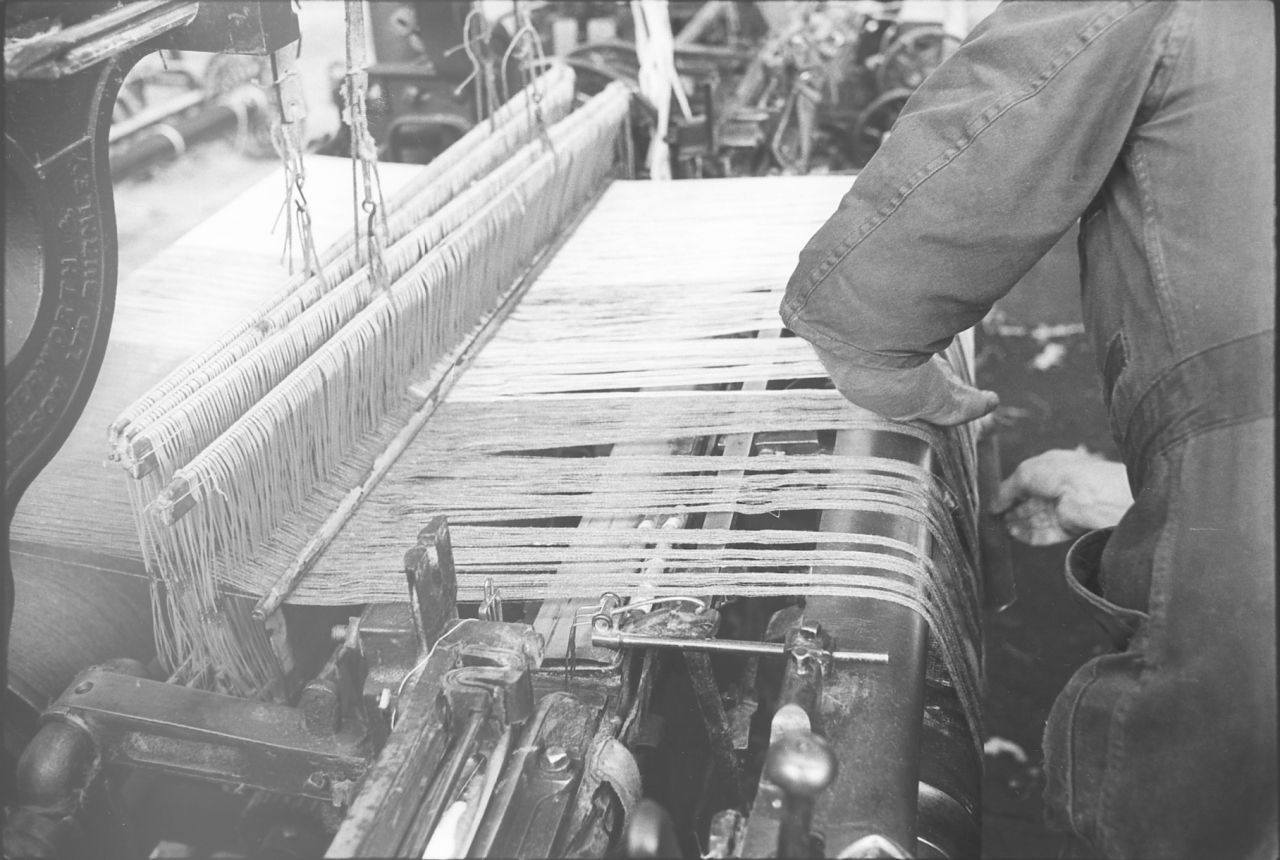

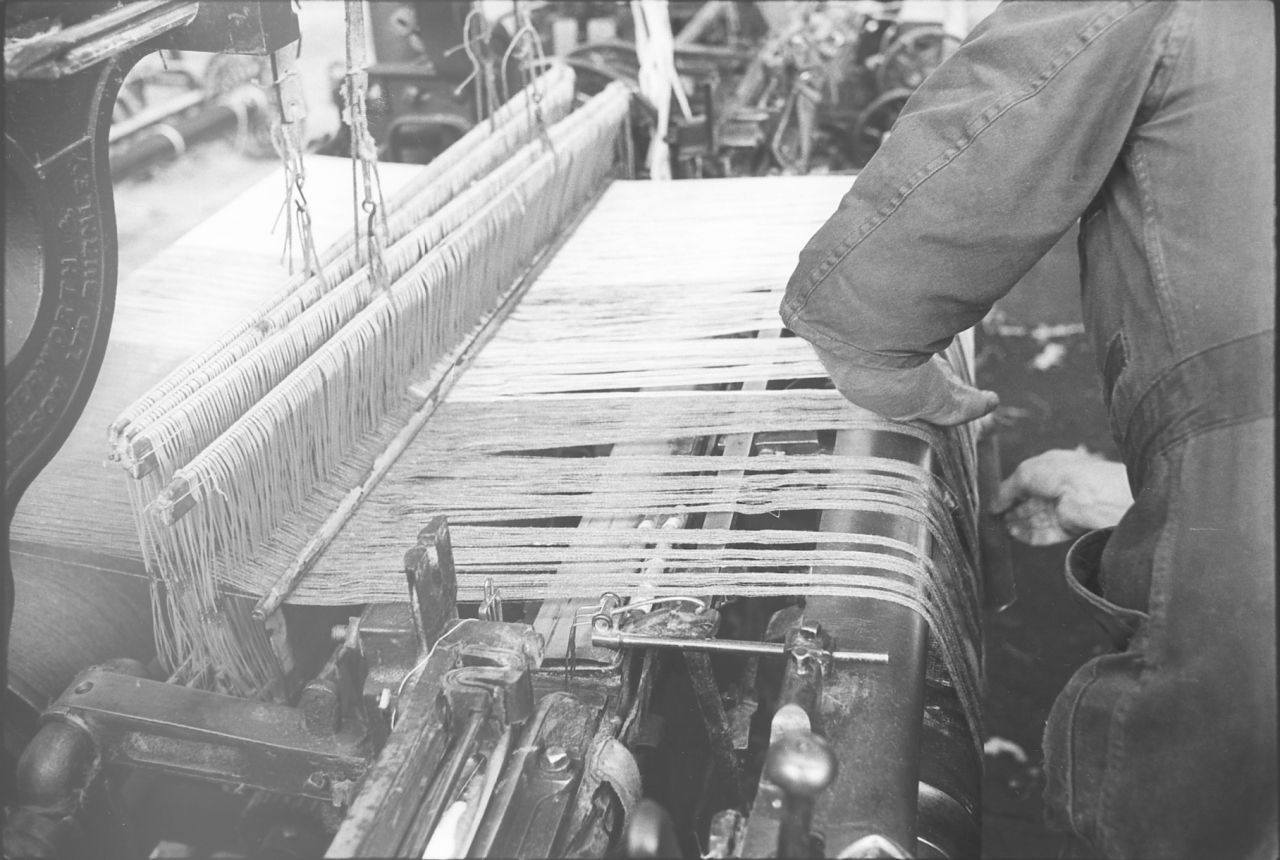

Now then, when you were on about your mother catching you in Calf Hall Dam you said that when she chased you down the road she were belting you with a picking band all t’time. Now, what’s a picking band?

R-It’s a piece of leather used on a loom.

Another thing, I remember you saying ‘witchered.

R-Oh well, it means if you get your feet wet.

Now when you went for that sand and that lad said ‘Eh what a nice arse you’ve got Mrs Yates, who were that?

R-That were a bloke called Raymond Riding.

When Fred got his first job, did you say he was hawking milk?

R-He were a milk boy aye.

Can you remember how much he was paid?

R-Three and six a week.

How old were he then?

R-He’d be about nine or ten I suppose, because later on, oh I were a lather boy later on.

Who was Fred working for when he was hawking milk?

R-A farmer called Taylforth.

Oh, would that be Dennis Taylforth’s father?

R-Calf Hall Farm. I remember they called the horse Captain, he used to gallop along, farting. Because as Fred grew older and I grew up a bit I got that milk job, it were like brother to brother.

Same money?

R-Aye, t’same wage, three and six. Then t’farmer’s wife used to give me us an egg or two. I’ll tell you a little tale about that, [I’d got] me first new suit wi’ long pants. We used to go up about half past three in the afternoon, to help to muck out. We finished mucking out and I were just leaning, brush and shovel up against the wall, outside and a bloke called Willie Ralph says ‘Bring t’shovel here Ernie, there’s a cow going to shite’. So I run in with a shovel, put it under its tail and it coughed.

Were it in summer?

R-Aye, it were in summer, it had been out on’t fog.

Oh, reight, reight grand fog muck, you’d be a fair mess then?

R-Oh, I were off work that night, I didn’t tek t’milk.

Did you used to take the milk at night then?

R-Oh aye, morning and night.

[Fog is the local name for the aftermath, the first sweet growth of grass after haymaking which is very juicy but low in fibre. It makes the cow’s muck very thin, green and evil smelling. When the cow coughed, Ernie would get it full in the face. There is another small point here, normally in summer, the only time the cattle would be in would be for milking. Because they were hawking milk in the days before refrigeration and taking it twice a day, you would expect them to take it as fresh as possible. Ernie says he used to go up there at half past three in the afternoon. This suggests they were doing an afternoon milking so as to have the freshest milk possible for delivery. There is a corollary to this, ideally, milking should be 12 hours apart so the morning milking would be very early in order to have the milk ready in time for the first delivery.]

R-And most mornings you were late for school and got t’stick.

What time did you go round in the morning with the milk. What time were you up?

R-Oh it’d be fairly early. We finished taking the milk, most of it, by school time, nine o’clock so they must have started about seven o’clock.

Did you go to the same customers night and morning?

R-Yes, winter and summer.

When you were a lather boy, how much did you get there?

Three and six a week but that was slavery. Every night after school at four o’clock, I used to go there, to Billy Demeline’s. Mrs Demeline used to have a little tea ready for me you know, she were very good to me really. But moneywise, it were hopeless. Every night after school, four o’clock, until the last customer came in at night, that could be any time up to eight o’clock at night during t’week. Saturday, all day Saturday till any time at night. Three and six.

Whereabouts were that shop?

R-Next door but one to the Seven Stars, it’s still there now, it’s Woodworth’s watch making shop.

That’s it, aye. That were a barber’s shop?

R-Aye, it must have been a barber’s shop for oh, years and years.

And, lather boy, your job’d be sweeping the floor up and lathering them up.

R-Lathering, all the [customers for shaving] there were two models in that area you know in them days. [Ernie is referring to the two ‘model lodging houses’ that were down Butts. One of them became a garage, the larger one, further down Butts became Briggs and Duxbury’s builder’s yard. They are both built of Accrington Brick. They were used by the weavers who had no permanent address in the town.] Where all the tramp weavers used to live.

Which were the two models?

R-Well, that one at t’bottom of Butts and what is Briggs and Duxbury’s woodyard now.

Oh, was that a model lodging house as well, the red brick building?

R-That’s right.

I didn’t know that. And the money you earned, did you tip it up to your mother?

R-Oh yes.

All of it?

R-Oh aye. Well we used to get a bob back you know. But in any case, for a shave it were twopence halfpenny and a lot of customers used to give me the odd halfpenny so I made a bob or two that way.

How about school meals?, did you ever get any meals at school?

R- Oh no.

Can you ever remember anyone getting a free meal at school?

R-Never.

How about medical inspections?

R-Oh aye. The nit nurse used to come round what, every week. And the dentist but not very often. There were no fillings, they were out if they were rotten and there were a lot of rotten teeth. Like I’ve said before, bow legs and rotten teeth used to go like hand in hand.

Did the dentist work at school? Did he take them out at school or did you have to go to him?

I don’t remember, I think he worked at school.

How about the doctor coming round to school, looking at you.

R-Never saw one.

And the attendance man?

R-Oh yes. You’d got to be there, it were, well you know, he’d come to your house, he wanted to know where you were.

What did they call him? Was that what they called him, Attendance Man, or was there another name round here?

R-School Bobby, that’s what they called him.

Were he in uniform?

R-No, but he were a very strict man as I remember, it were t’same feller all the time I were at school.

Did you know his name?

R-No, I don’t remember his name. But I had no problem, as I always went to school, if I weren’t ill like.

Where there a lot didn’t go?

R-Oh, plenty.

What reason mainly, just laiking about?

R-Oh aye, and then it weren’t a very happy time at school then. They used to whack you with t’bloody stick for no reason at all sometimes. I can remember getting caned and fainting, Mr Turner, from Earby,

Yes, we’ll get on to school in more detail in a minute. Can you remember the school inspectors coming round?

R-Yes, and if there were a pupil that were a bit brainy, you know, and t’master used to say “Stand up Roberts and answer questions for Mr So and so.” Not Roberts very often, but sometimes.

We were on the other week about lending money and I know that you did tell me during the week that you’d remembered someone that lent money. Who was it?

R-Isaac Levi.

Was that the same Isaac Levi that had a shop down Earby?

R-Yes, well, I think it were his son had that shop in Earby. But this is a long while after Isaac Levi had this little shop in Walmsgate.

Whereabouts was the shop in Walmsgate?

R-You know where Billy Blackburn lives now? Well, it were there.

Oh, the end house in the row where Savages started up? [16 Walmsgate]

R-That’s right.

That’s it, yes. And did he lend money for interest?

R-Yes.

Any idea what the interest was?

R-No idea but he were a very good man were Isaac. I mean, he helped a lot of people. I’ve heard, but lots of people talk, in fact I’ve never heard anyone cry Isaac down. Most people that knew him said he were a nice chap.

And you did mention during the week that Savages first started up as a greengrocer’s business in Walmsgate. Whereabouts was that?

R-That’d be next door but three to Isaac’s.

Where the butcher’s shop is now? [8 Walmsgate]

R-That’s right.

What’s his name in the butcher’s shop now?

R-Alan Fielding [This was in 1978. In 2001 it is still a butchers but is run by Stephen Bell.]

That’s it Alan Fielding, and Savages started up there?

R-Me mother told me, she remembered him starting and he had a box of onions, they used to be in like orange boxes did onions, and a barrel of apples and I fancy he’d have a few vegetables as well.

Any idea when that was?

R-Oh. It must have been a long time since.

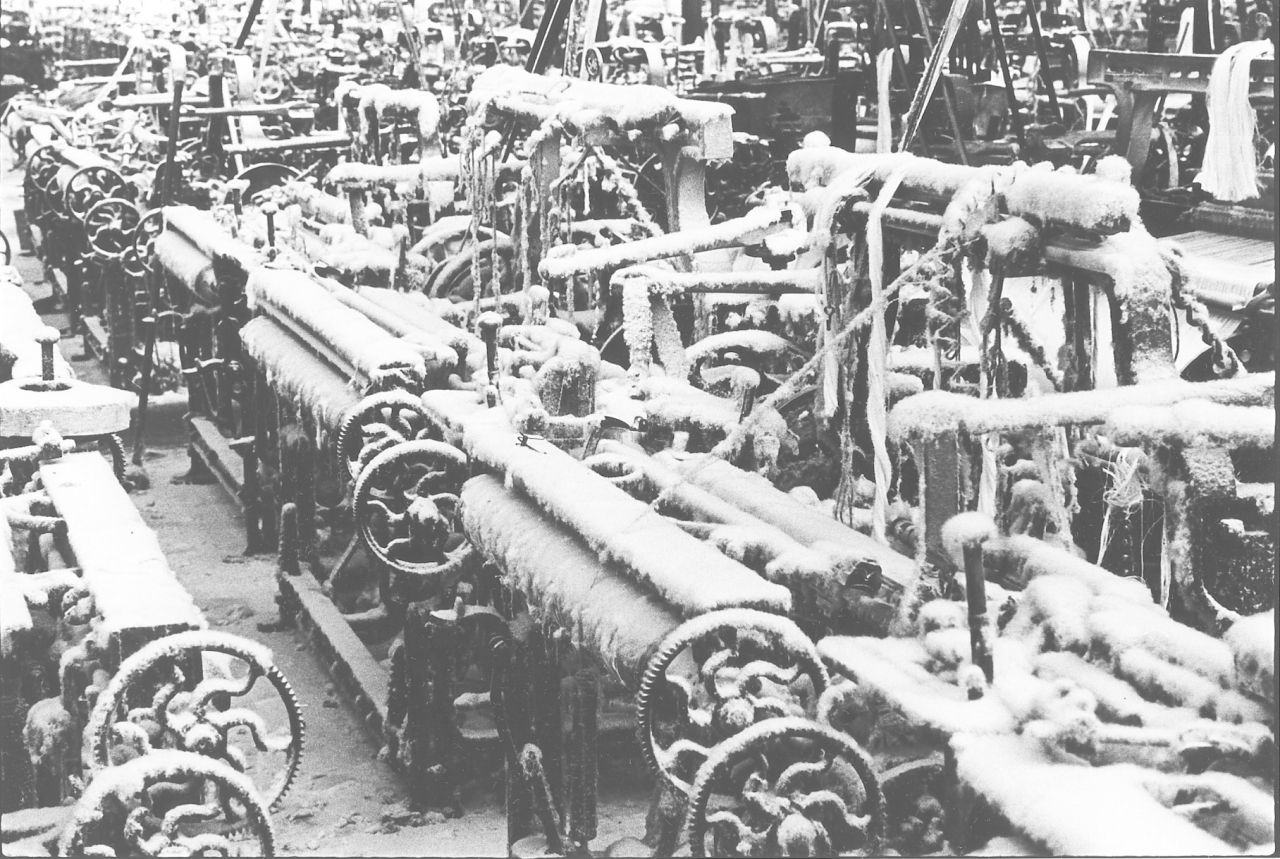

Yes. Now, while you were living down there, can you remember Bancroft starting up?

R-No, I don’t remember it starting up. I think it started in 1920 and I would only be four then.

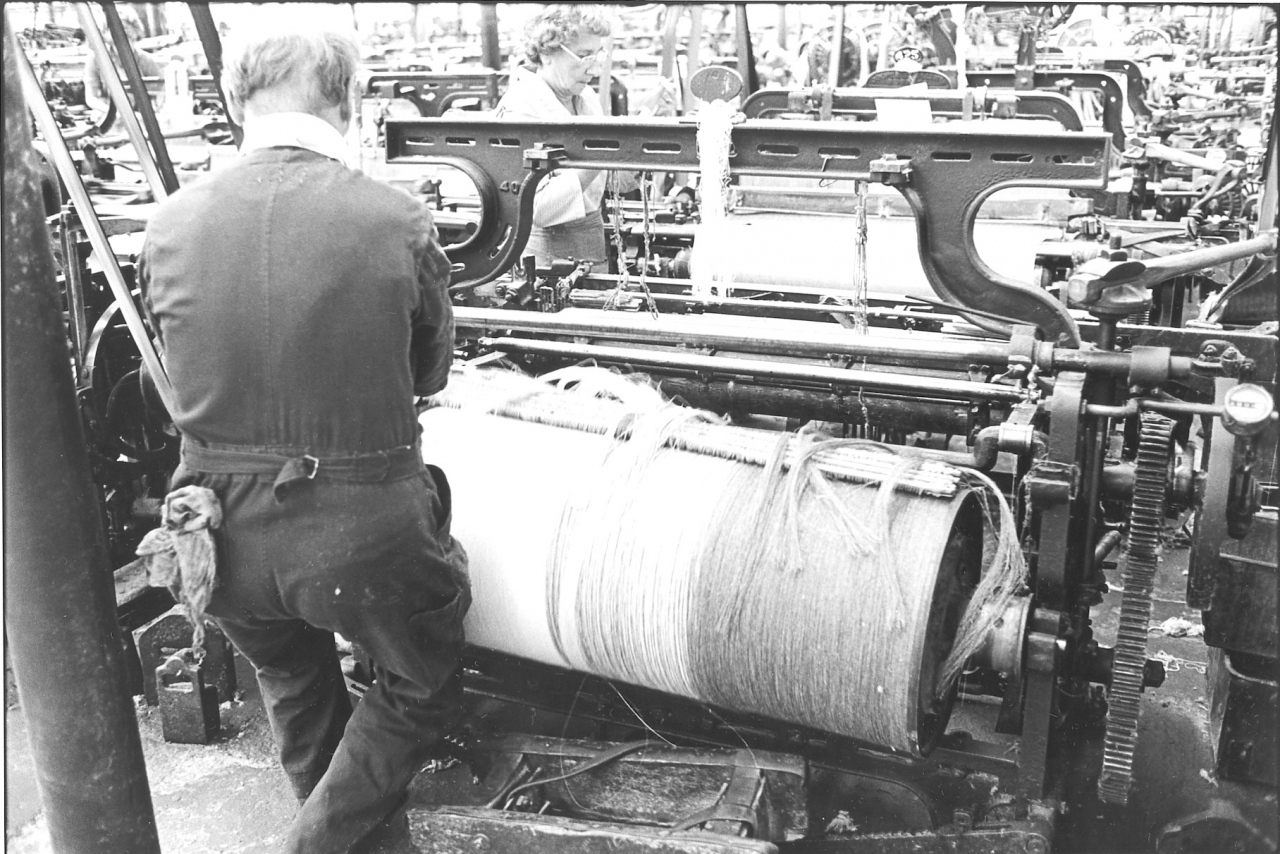

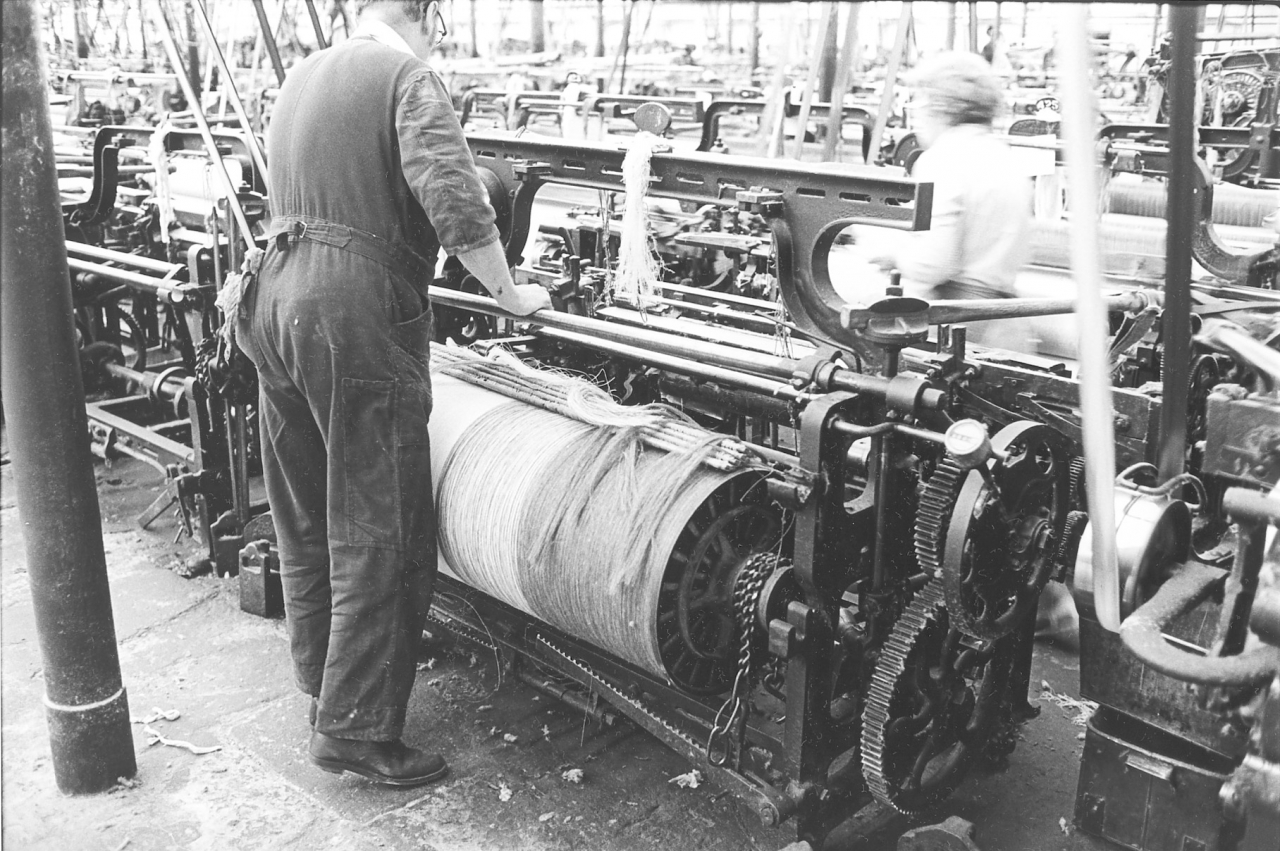

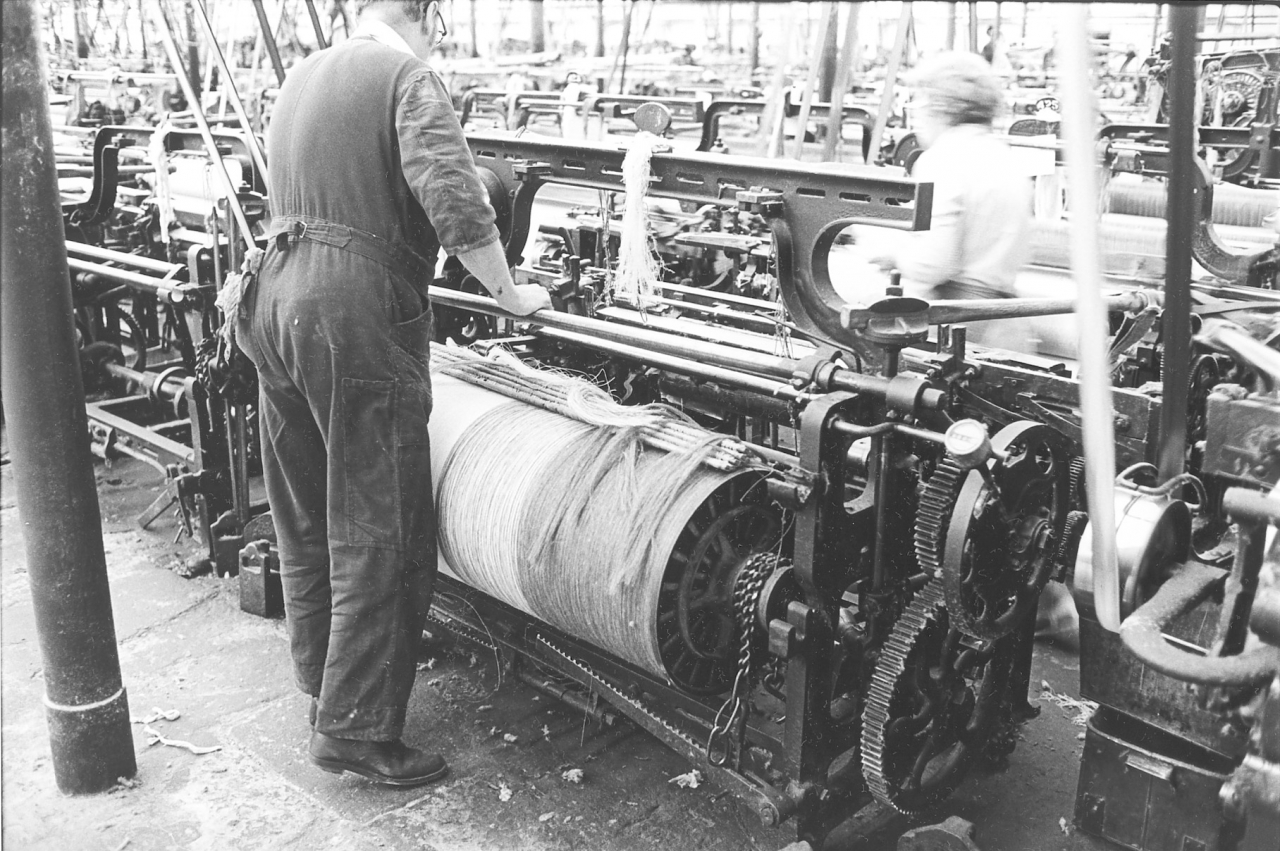

That’s it. You’ll be able to remember weavers coming up in the morning to Bancroft?

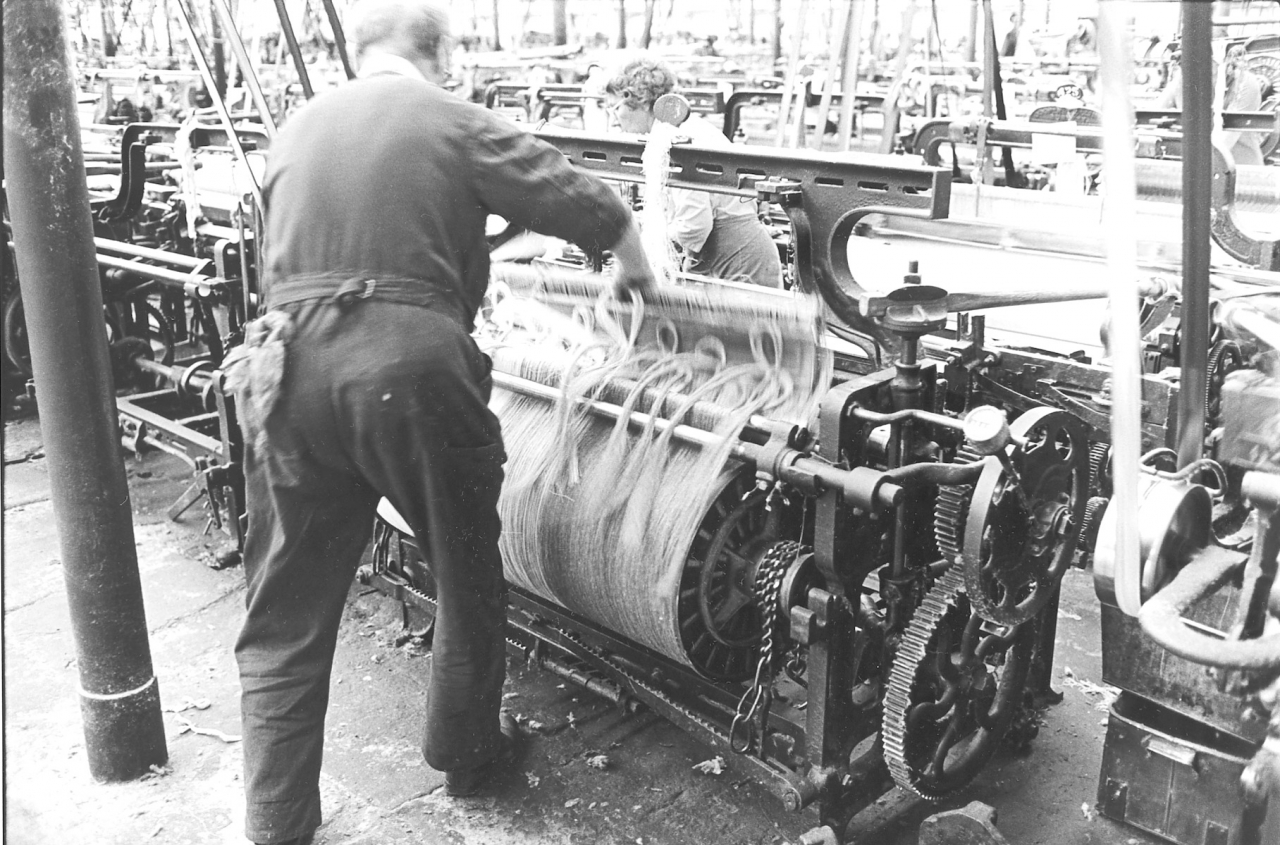

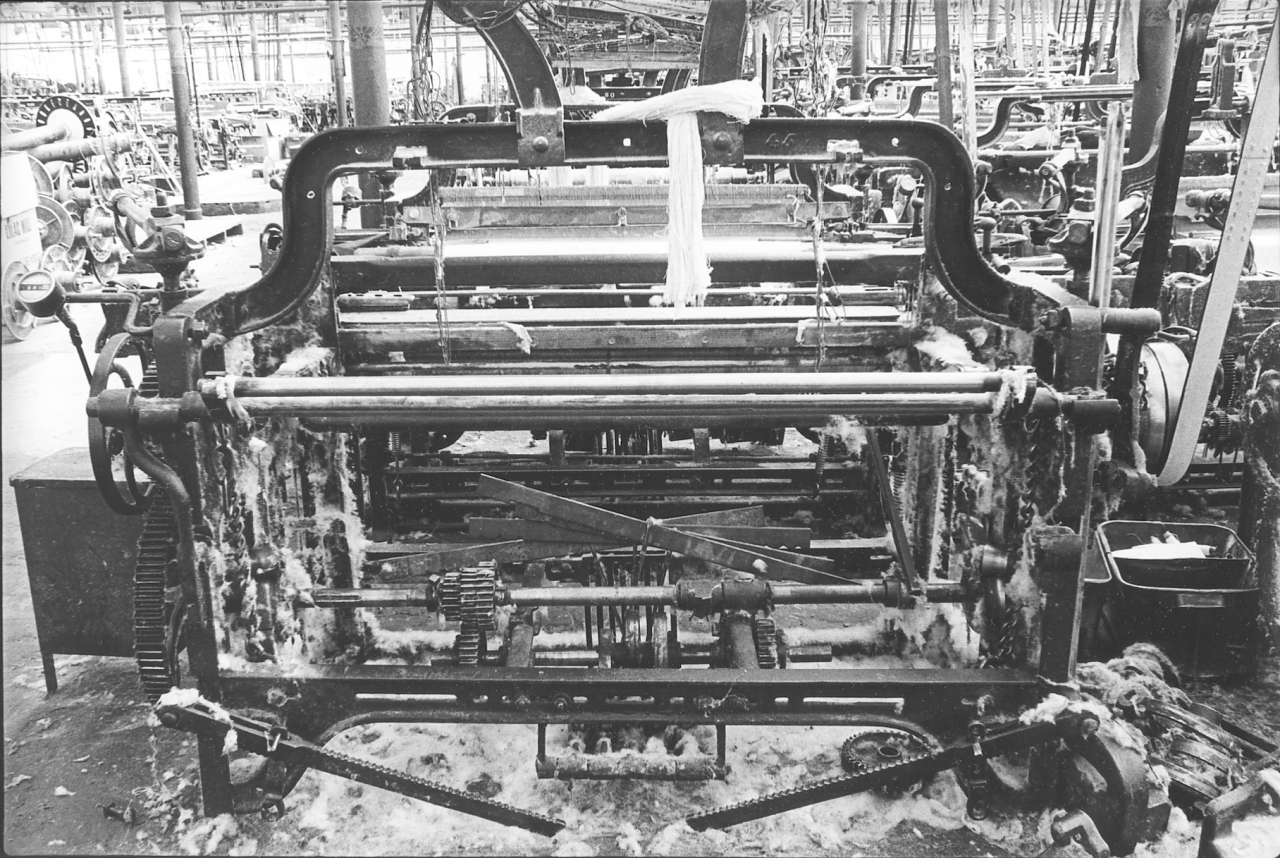

R-Oh aye. I mean Bancroft’s been like a permanent feature in my lifetime here. There used to be 1100 looms running. There’d be, what would there be, three hundred at least working up there in them days, so you can imagine when t’shop stopped, all them trooping down Wapping wi’ clogs on.

Aye, wi’ their clogs, wearing the street out. Good enough Ernie. Now then, there’s something else come up here, about Isaac Levi being a bookmaker as well.

R-Aye, That’s right, he was. And he were a decent bookmaker as well but they did tell a tale about him being diddled a few times before he tumbled to this dodge. This town, Barnoldswick, it’s always been a gambling town, there used to be a gambling club, they called it the Betting Club, up Market Street. But this trick that these fly boys played on Isaac, they used to go in wi’ a bet, and he’d say, ‘Put it in the shoe box’. You see he’d have a shoe box, maybe on his counter. He’d read the bet of course and he’d say to the bloke, or he might throw it into the shoe box. But somebody had a bright idea, they got two pieces of paper and wrote a winning bet out and then stuck another bet on top wi’ a bit of spit. Well, Isaac threw both bets in the box and by the time reckoning up time came this bit of spit had dried and these two pieces of paper fell apart. So there were a winning bet in the box to start wi’. Twisting buggers, I don’t like twisters. Oh pigeon flying, all sorts of competitions, t’bowling green at t’Conservative Club ground, you know it were a beautiful bowling green that.

Whereabouts was the Conservative Club ground?

R-Butts.

Whereabouts at Butts?

R-Well you know where the welfare place is now, the clinic? Well sideways on to that. You can see it’s a been a bowling green even today. It’s fenced off now, it belongs to TB Fords [In 2001 it was Carlson Ford] but they used to have, happen twice in a summer, they’d have frizzles and all us Wappinger lads used to get to know about these frizzles and you know, we’d be there.

What’s a frizzle?

R-Oh, they used to fry in big trays, chops and eggs…

What they’d call a barbecues now.

R-Well, aye, I suppose they do. Chops and liver and bacon and eggs, oh it were a real bloody do. And they used to feed us, these chaps, Tories, aye Conservative Club.

How did Isaac go on wi’ his bets?

R-Oh well, from all accounts he tumbled it. He wouldn’t summons ‘em, he’d just bar ‘em I suppose. If they showed their face in the shop he’d just say ‘out’. Did I tell you, when we were coming home from school, if we were feeling devilish, his door was always open, we’d stop at his door and shout inside, ‘Who Killed Christ!’. And run like hell.

There you are! Oh well, we’ll get back to these questions about life in the home, I’ve no doubt we’ll digress again but still…… Were there any games that your mother played in the house with you, or that you played between yourselves?

R-No, I don’t think so. I think we had, what did you call that game where you used to pull the spring and t’ball used to fly down?

Oh God! We’ve got one at home. You’re not supposed to be asking me the questions! I know what you mean.

[It was bagatelle of course.]

R-We had one of them for a long time. Aye, if the weather were really bad we’d play cards, I don’t know, but there were, there were never happy families. Oh, snakes and ladders, I think we had a snakes and ladders game at one time. But we’d be gambling!

I were going to say, were there dice in the house.

R-Aye. Aye, we’d be gambling, we were gamblers. I tell you what, Fred my elder brother once offered me a shilling if he could throw, I think they were magpie eggs, at me standing against the wall across from John Street. So I said ‘Alright’.

A shilling?

R-A shilling, aye.

How old were you?

R-Well, he’d be maybe fourteen or fifteen and I’d be what, Ten. Aye.

It were a lot of money.

R-So it were. I stood up against the wall and he threw these eggs at me and missed with every one. But I didn’t get me shilling. Happy days!

Can you remember ever having a newspaper?

No, I don’t remember a newspaper.

Or a magazine?

R-Later on maybe, but I think she used to get the Daily Sketch, my mother, not every day, just occasionally. How much were they then, a penny? But we never had a paper delivered.

Did she ever get a woman’s paper of any sort, you know, like Woman’s Weekly or anything like that.

R-No, but she used to read. I don’t know what she read, it’d be love stories I suppose. She were only a young woman when me father died you know, thirty odd. And she never had another feller. And she were a good-looking woman. She used to get pestered occasionally but no, she thought that much about her kids, she were a good woman.

Aye, must have been.

R-She were.

Must have been Ernie. Did any of the family belong to the library?

R-No.

‘Cause I know you are a great reader aren’t you.

R-I’m a reader but I’ve never been a library man. If I have a book it belongs to me. I couldn’t be responsible for someone else’s book.

Yes, would you say you were a reader then?

R-Oh, I’ve been a reader all me life, right from penny comics, Wizard, Hotspur.

Who used to get them for you, did you get them yourself?

R-I used to get ‘em meself. I were always earning a copper you know, running about, running errands, I’d go anywhere.

How about books in the house? Can you remember any books in the house?

R-Only t’rent book!

That wouldn’t make reight good reading some days! Could everyone in the family read and write?

R-Oh aye, we were all fairly good scholars.

Who were t’best scholar?

R-I think I were t’best scholar.

Aye, I think you might have been. How about toys?

R-Well, after things bucked up you see we’d have toys.

Can you remember any?

R-Not really, but you’re on about musical as well, I remember getting a musical box given. It were a lovely thing, light coloured wood you know, and it used to play these tunes, I forget what the tunes were but it were like a brass cylinder with all them spikes on you know. That silly bugger Wilson decided to change the tunes so he kept knocking the odd spike out here and there, he ruined it. I were only on to him a few weeks since, that musical box today must be worth hundreds of pounds, it would have been, but it were ruined.

Who gave you that?

R-You remember Jim Barrett? You must have known Jim Barrett, bricklayer? He lived up at Springs Farm.

How old would you be then when he gave it to you?

R-Oh, fourteen happen.

When your mother had any spare time in the house what did she used to do with it? What did she do with her spare time at home?

R-Eh, I don’t know. I don’t think she ever had any spare time really. I can’t remember her sitting about, but we were never in much you know. If it were fine we were out.

Yes, but in winter you’d be….

R-Oh I don’t know, we’d still be out doing sommat. I mean it were Fifth of November, chubbing, [Chubbing is a dialect word for gathering wood.] Christmas, singing carols, earning money. There were me, Tommy Lambert and Tommy Harmer. Just us three, I used to have the candle in a jar and Tommy Harmer played the mouth organ and Tommy Lambert used to play on the piccolo. Well we always called him ‘Shuffy’ and he weren’t bad on the piccolo. We were playing one night, ‘While Shepherds watched their flocks’ or something and Tommy’s piccolo started gurgling, so we had to tell him to wipe his nose. We used to make a bob or two at Christmas and New Year’s morning we used to go to t’Model with t’brush and black face collecting off th’old tramp weavers. Aye, always a shilling or two to be made somehow. I used to come up here, weeding at sixpence an hour.

What, to good houses like…..

R-Aye, knock on’t door and say ‘Could I weed your garden?’ like. Regular customers. There were three teachers used to live in that corner house there, where that model is now, lodging house. Just across there. And they were , I used to come up here regular, every week.

Aye, What do you call that house, is it Springbank or something like that?

R-Sommat like that.

It was built the same time as the mill they reckon weren’t it, that house. Somebody once told me that.

R-Could have been.

I think one of the Nutters built that house.

R-Anyway, when I were weeding for them they’d call me in at lunch time, it must have been a Saturday happen when I were doing it. One of the women would have a little table set out with a tablecloth on and a nice little meal. I’d have a little bit of lunch and back out into the garden, pay me a tanner an hour.

How old would you be then?

R-About twelve happen.

Initiative Ernie!

R-Oh aye. Once I’d learned which way the road turned I can’t honestly say I’ve ever been hard up ‘cause if there were a shilling to be made I’ll be there. And you can always make a shilling, I mean there’s a lot of unemployed today and they’ve no need to be.

Yes. No you’re quite right. What time did you get up in a morning usually?

R-Are we still at John Street?

Yes, John Street.

R-Well, school time, it’d be early happen about half past seven, eight o’clock.

How about the milk?

R-Oh well, when t’milk job started I had to be up by half past six.

How old were you when you started on the milk?

R-Well, I were only a little lad when I were a lather boy, and it were after I were a lather boy I were a milk boy, oh, I’d happen be 11 or 12 happen. I were a milk lad for Taylforth and I must have been a good man at my job because then a bloke called Brewster, he kept a farm across from Calf Hall, shilling a week more so I went milk-ladding for him, four and six a week, busy days.

What time did you go to bed at night?

R-Well, we went to bed when we were tired, there were no telly you know. Maybe ten o’clock. But we used to go to the pictures a lot now, we’ve got to the picture days now. Pictures Monday, Tuesday, miss Wednesday, Thursday and Friday and see a different picture every night.

Why did you miss Wednesday?

R-Well, Programme were Monday Tuesday and Wednesday at t’Majestic, and Monday, Tuesday Wednesday at the Palace. So Monday Majestic, Tuesday Palace, Wednesday I don’t know what, Thursday Majestic and Friday at the Palace.

How about the Alhambra, did you ever go there?

R-No, I can just about remember the Alhambra, I can remember it being burned down. {The fire was in April 1923 so this would be in the ‘Hard-up’ days. Ernie would be seven years old when it burned.] No, I never went, I can’t remember going to the pictures there.

Aye, of course it stood on the piece of land next to the bowling green you were on about.

R-Yes it did, it stood where the welfare place is now. And then there were an open market there you know after it were burned down. That were interesting and then the fairs used to come on there. It’s been a useful piece of land has that and it were a good courting shop later.

Is that right? Aye, we’ll get on to that later Ernie. If you were in at night, it were gas-lit were that house?

R-Oh aye.

Would your mother ever say anything like we’re going, we’ll not bother lighting t’gas, we’ll go to bed or did you just used to sit by the fire light?

Oh no, we’d go to bed if there were no, sometimes we didn’t have any gas you know. It’s no good sitting having no coal, Oh we used to get a bit of coal though, they used to deliver coal to Calf Hall and t’road were in a poor state so when t’wagons were going down loaded they always used to spill a bit so we used to go down and collect that. And then we’d walk past the stack and hit it with a stick and what fell off went into t’bucket. So we used to, oh and Clough just across the road were on coal as well you know. We wouldn’t be without a fire for long.

Is that right?

R-Oh, necessity knows no law.

No, you’re quite right. How about coke from the gas works, did you ever go there?

R-Yes aye, we used to go to the gas works. You know the fiddle with the little truck? [We had a little wheeled truck we used to collect coke and] when you go in they used to weigh your truck but under the sack you’d have a couple of bricks. Go in to the yard, up to the stack, there used to be a feller there but not always, you used to weigh your own, half a hundredweight, a sackful. Well, you’d leave the bricks there, there must have been enough bricks to build a house ‘cause everyone was doing it. On your way out you got two bricks worth of cinders for nothing. I once went for a bucket of creosote, and coming out you used to report to th’office you know. Well, I weren’t very tall so I bobbed down and walked under the window so that were another bit of profit there.

What were the creosote for, somebody’s hens?

R-Some hen keeper. [For painting the hen cabins to protect them against water and rot.]

Can you ever remember being taken down to the gas works with whooping cough? It were fairly frequent were that weren’t it.

R-I’ve always had a good chest, good job. I’ll tell you what they used to tell, you know when they used to come round tarring the roads?

Aye.

R-Whether it’s true or not I don’t know, I hope it isn’t true, but there were a baby with whooping cough and her mother were holding her up by the boiling tar and the poor little bugger fell in. Whether it were true, it could be true.

Aye, easily because it were done. Newton were only saying the other day about being taken on to the top of the retorts when he had whooping cough and Vera was as well. [My wife. SCG.] I have an idea one of her relations worked at the gas works. Now what makes you say the gasworks was an interesting place?

R- Well I mean, the coal went in there and I remember one time, at school, we went on a conducted tour and it were interesting were that. We did an experiment with a clay pipe. A few little bits of coal in the bowl, seal it up wi’ some clay, put it on the fire and within a few minutes you got a light on’t end.

That’s it, that’s how they first discovered coal gas.

R-Now I suppose that’s a trick that’s been handed down.

That’s it, were clay pipes common then?

R-Oh everybody [smoked ‘em]. I had an aunt once that smoked a clay pipe and she used to enjoy it. I used to go errands for her to the Co-op for this tobacco. I mean nearly everyone was a member of the Co-op in those days. She sent me for this twist and I noticed he never used to weigh it this fellow. He used to put it round my neck and cut it off but he also used to cut a little bit off and there were always a long piece and a little bit in this bag. So I thought one time, I’ll pinch that little bit, she’ll never miss it, and try it. Right, get a clay pipe. So I pinched this little bit and when I got up to see me aunt Annie with this twist she took it out of the bag and she says Where’s the jockey? I says What jockey? Oh I says, it’s here. She says You little bugger, tha were going to pinch it! And they called that bit ‘the jockey’ and everyone who bought twist in them days had to have a jockey besides.

Did she ever chew it?

R-No, I don’t think she chewed it.

What sort of twist were it, can you remember?

R-Black twist.

Aye, there used to be some called ‘Lady’s Brown’, it were very thin.

R-Oh, I’ve seen that. And there’s some reight thin like bootlaces.

Yes, well that were very thin that Lady’s Brown but there were some very thin black stuff, that were chewing twist.

R-Oh but this were reight thick stuff, black as ink.

Aye, thick twist.

R-And the jockey!

And the jockey, well you live and learn. Of course, you were a bit of a beggar for experiments weren’t you?

R-Oh aye. It’s a sure cure for tooth ache you know, a bit of black twist. But as for the experiments, we’d have a do at owt.

Aye, that’s it, how about gunpowder?

R-Oh, don’t mention gunpowder, it’s a miracle I’m here! This were at John Street. Fred, me elder brother, had a muzzle loading shotgun. We must have had a dresser at this time and he used to keep the gunpowder locked in a cupboard but I found out if you pulled the drawer out you could get your hand down into this cupboard. I did this many a time, take out the powder horn, and we had a steel fender as things had bucked up. The horn used to have a little stopper on the end and I used to press on this and open it and run the gunpowder along . Then I’d get the poker and get it red hot and touch it to one end of the powder and it’d go psssssh! And if any of the kids were in I’d say Continued in our next! But one day I’m doing this trick and the bloody lot went up, big explosion, burnt all the skin off me face, fireplace hanging off be one leg. The old girl next door, she’d been bedfast about three years and she fell out of bed, There were hell on and didn’t I cop it! I went to the pictures same week and I were like the invisible man, all bandaged up.

Who bandaged you up?

R-Oh it were me mother, she didn’t dare go for the doctor, it were illegal were this gunpowder and he might have reported it to the police or something like that. But he were a good hunter were Fred. This muzzle loading shotgun, we wanted a Sunday dinner maybe and he had just enough gunpowder for one shot but no pellets. So he got an old bicycle wheel and took the ball bearings out of the hub and loaded it wi’ that and out he went. He came back with a hare and he only had one shot. Aye, he were a good provider.

Where did he get his gunpowder from, do you know?

R-No.

If your mother had sent for the doctor she would have had to pay wouldn’t she?

R-Possibly, oh, but he used to come every week did the doctors man, sixpence a week.

Oh, she used to pay?

R-Oh Yes.

So, she were on like what they used to call the panel, they had a panel didn’t they.

R-Well, it must have been, it were sixpence a week for ever, Dr Glen’s book.

That’s it, and if you were on Dr Glen’s book and you were poorly…….

R-Well, up to being 12 years old I were always poorly, so t’doctor were coming on and off you know. I told you once before about six death beds. When I were about 11 or 12 Doctor Glen told me mother I only had three months to live. So she said to me, she didn’t tell me I were going to die in three months, but there were a grocer’s shop, Bonny’s, we had a tick book there. She said to me ‘You can go and get anything you fancy.’ Eh, I thought, that’s a rare do. So, Woodbines, ham sandwiches, meat pies, eh, owt I fancied. It only lasted a week, once she got the bill that were stopped!

How old were you then, ah, 12 weren’t you. Were you smoking Woodbines then?

R-Yes, I were 12. You started off smoking tea leaves but then we worked up to Woodbines.

Did your mother know you were smoking Woodbines?

R-No, she might have done, she never objected to me smoking anyway because I were dying, I were, I were dead next week. I fancy she thought it’s no good getting on to him.

How about pets, did you have any pets?

R-Oh aye, we allus had sommat. We’ve had all sorts. Jackdaws, always a cat, always a dog, I once had a cuckoo, that died. Well, I think I choked it, I gave it some bacon rind and I don’t think it did it any good at all. I were sorry though, it were a nice bird.

How about dogs, did you use them for rabbiting?

R-Aye we allus did., we allus had a dog like, but old Jack, that were a dog that seemed to grow up wi’ us.

What sort were it?

R-Mongrel, Oh no, we never had owt wi’ a pedigree.

Did your mother smoke?

R-I think she had an odd fag but I don’t think she smoked really. I think she used to like a tot of whisky, not that, she didn’t go out boozing, I think we used to have an odd bottle in the house.

How much were a bottle of whisky then, can you remember?

R- Seven and six. Oh I remember what I used to go for, a noggin of rum occasionally, in’t pub. Take your own bottle and they put a noggin of rum into it, it wouldn’t be so much. May be when she weren’t feeling too well.

When you say a noggin, how much would that be, it’s more than a six-out isn’t it?

R-Happen a couple of six-outs.