TAPE 79/AO/01

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 11th of MAY 1979 AT NUMBER 9 SACKVILLE STREET, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS JACK PLATT AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Jack Platt in 1977.

[Mrs Mona Platt was present and helped Jack out here and there. Her contributions are clearly marked.]

So what year were you born Jack?

R- 1905.

1905, so that makes you 74 years old.

R - This month.

This month, what date?

R - 29th.

29th of May, that's it and where were you born Jack?

R - Cheesden Pasture Farm, Norden. Rochdale.

Aye and what were your dad doing, was he farming there?

R- Then? Yes.

Yes.

R - Yes.

That’s Cheesden Pasture. Do you know I've an idea I know that farm.

R- Aye.

Anyway what made him move across here Jack, any idea?

R - Well I don't know really. You see when I were young I went to live with me aunt and uncle at Royton.

Aye?

R- I don't know why they shoved me away like but I went and then when I came back to them we lived at White Cottage on White Moor, Fred Cutler had the farm and we lived in the cottage there, White Moor.

Yes.

R - That's when I come back to me mother like.

Aye.

R - There were only me mother then like, you know and what you call a step-father, you know.

Aye, and they came over to Barlick.

R - And then from Barlick .... from Barlick. we came to Tubber Hill.

Aye.

R- You know from White House we came to Tubber hill.

Yes.

R - And then from Tubber Hill we went to Rawtenstall and then from Rawtenstall we come back to Amen Corner.

Which is Amen Corner?

R- Higher Lee Cottages below Lane Head, them old cottages below the water works, you know, down in the bottom there.

Amen corner lying derelict in 1979.

Aye.

R- There were four cottages.

Aye. Are they still there?

R - Well, the remnants are, you know, the walls are but they're pulling 'em down.

Aye.

R- And from there again.. I were married from there,

Yes.

R- I were married from there, and then come living at Tubber Hill. Like you know, after I were married.

Aye. Now so that's a fair number of moves in a short time isn’t it, really?

R – Well, in a way yes. I’m spanning a time then from being about five year old to being about nine.

Yes. What would they be doing really, looking for work do you think?

(50)

R- Well they were up and down because it were, it were really bad for fellows, they went to different places looking for work, yes.

Aye five year till nine. Let’s see, that’d be about 1910 to the beginning of the first world war wouldn't it?

R - That's right..

Aye.

R - Well war broke out while we lived in that White Cottage, on White Moor.

Aye.

R- And then there were a do come out, they were condemning all them. It's still a good cottage is that but we’d to move and that's why we came from there to Tubber Hill.

Aye.

And did your mother work?

R - Me mother walked from there to Barrowford and they started at six o'clock at morning then.

Aye.

R- And if they weren’t there at six o'clock they had a weaver put on. [their looms]

Aye.

R - And there were no buses, no transport whatever, so you can tell what a rough do that were. That’d be, how many mile from White Moor to Barrowford?

It’ll be a good three mile.

R - And then after a year or two she thought she'd get nearer her work so she started down in town, Plummer’s they called it. It were Windle’s at Crow Nest and she thought that were near and that were what? That’d be three..

(5 min)

Well that were thick end of three mile.

R - Yes that's what I say.

And she were weaving of course?

R - She were weaving, yes.

Aye. which house do you remember best Jack, of the one's you lived in when you were young.

R - When I were young? Well, White House on White Moor.

Aye.

R - I remember it.. well, yes, you know during me youth, I remember that more than any of 'em.

Right, well let's just pin down exactly what and where that house is. When you talk about White Moor..

R - You know when you pass Stone Trough Well.. [Jack means Gilbert Well and I never corrected him]

Yes.

R - Stone Trough..

Where the bungalow is.. [Wood End bungalow]

R- Next farm on your left.

That's it.

R - The first farm on your left. [White House Farm]

Aye. I know where you mean now, aye. I never knew..

R - Fred Cutler had it.

Aye, I never knew that that were the name of that farm; and you were living in the cottage there?

R - We were living in the cottage.

Aye.

R - Half-crown (2/6d) a week then, only we didn't pay no rent 'cause I used to help Fred.

Is that right?

R - Aye, we used to get eggs off him you know and live rent free.

And how old were you then?

R - Oh about nine. He used to take me all ower with him and he’d never take no money. I used to run him errands and all sorts. I went hay making for him years after I really left there.

Aye.

R - For Fred.

What do you remember about the house, what were house like, how many rooms were there down stairs?

R - Oh there were just a living room and a little kitchen with the old stone sink and two bedrooms and that were it like.

No bathroom?

R - Oh no, no bathroom.

Outside toilet?

R - Outside toilet yes.

And what were that, dry toilet, bucket?

R - Bucket aye, th’old bucket you know, aye.

And the council wouldn't empty that, you'd have that to empty it yourself up there?

R - Oh that were to empty yourself, that went on the land I think did that.

Aye.

R- You know, farm land.

Aye.

R- It went on the land.

Aye. How about, what were the floors?

R- Flag.

Aye.

R - Flag floors.

Carpet?

R - A bit of an old rug I think, bit of an old peg rug, what they used to peg there selves then.

(100)

Aye.

R- Wi’ all bits of cloth cut up, you know.

Aye. Ever use sand on floor?

R- Oh yes, aye. She used to use sand did me mother on the kitchen floor an all you know.

Aye, where did that come from?

R- Now I can't tell you that, I think out of the farm yard, because I think Fred used to get it, you know, they'd a flagged floor in farm house. And a bucket full every now and again from there you know.

And that’d be done, what, once a week, sanding the floor?

R - Aye once a week yes.

Aye. Were there a stair carpet?

R - No, no stair carpet, stone steps.

Stone steps.

A - Stone steps aye.

Aye and were they wood floors upstairs?

R - Yes they were wood floors up stairs.

Aye. And how about cooking, what did your mother cook on.

R- Oh the old coal fire.

Aye,

R - There were no, you know…

Was it a range with a side boiler or was it..

R - No it had a side, hot water boiler, you know, where they filled a hot water boiler.

Yes.

R - And th’oven at t’other side what she baked in you know.

Aye. And how about having a bath?

R - Bath. Oh an old tin bath.

In front of the fire?

R- Front of the fire.

Regular night?

R - No, every now and then. [Jack and Stanley laugh]

Eh. Would you say they were hard up?

R - Hard up?

Yes.

R- Oh aye we were hard up alright.

Aye.

R - I didn't take much fault because I were in.. I were allus in the farm house, I really lived there more than at home. I only slept at home, I were never out of Fred’s but it were hard up days..

Aye.

R- Really hard up days, mmm.

How did it show mainly?

R - Well in every way. I should think me mother were one of the…. all she had were spent on food. I should think what we had on us backs did for Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday, you know what I mean.

Yes.

R- No Sunday changes.

That's It aye.

R – Th’old clothes and she were allus, she were allus good wi’ us. She'd allus see we’d sommat to eat, yes.

Ever known her going short to feed you?

R- Yes I have, yes I have. I allus remember one night she were coming home from Barlick, and I don't know if you'll ever remember it or not, but there used to be an engine at the top of Salterforth Lane, in that where they put the road salt.

I can’t remember it but I've heard of it.

R- Aye well I can remember it. I can picture it now and they used to take the rope down and pull the quarry wagons up, you know. You know out of the quarry.

Yes, aye.

R- Pull horse and carts up, hook on to the shaft and help the horse up. And somebody there took her wage off her one night when she were walking home from work, I can allus remember that. That were a bit of a hard week that week because she'd nothing then, you know.

(150) (10 min)

Took her wage off her?

R - Aye pinched her purse, they never get to know who it were like but I allus remember that.

Aye.

R - So like there were a few rough ‘uns in that day weren’t there?

Aye,

R - And that's a long time ago.

What would a weeks wage be then for a weaver?

R – Oh, about twenty two or three bob I should think. [£1.15p]

What would that be, four looms?

R – Yes, four loom. I think me mother had five though, I think so. No, she'd four, there weren’t many fives. It were men that had five looms then and sixes.

Aye, aye.

R - It weren’t a known fact for women, they were four looms, you know, four looms as a rule.

How about going to school Jack, where did you go to school?

R – Foulridge. That’d be two mile wouldn't it?

Aye.

R - A good two mile.

How did you get there?

R- Walked it through the fields. Through the fields and down the big hill to Foulridge Station, across, and then up to school.

No school dinners then?

R - No school dinners no. I used to have to take our bit of dinners wi’ us, you know. Our Annie looked to that, me sister, she were older than us, you know and sandwiches, sandwiches. And then at tea time it’d be about what, seven o'clock would tea time. It used to take me mother that long to walk home you know. We had us tea about half past seven to eight o'clock I should think. We’d have a jam but' as we called 'em then tha knows.

She'd never have any time then to herself, your mother.

R - Me mother never had any time, no. No, no time didn't me mother, she'd a hard life had me mother. One of hardest lives I've ever known a woman to have really. I've telled you Mona haven't I many a time. [Mona was Jack’s wife.]

How old was she when she died Jack?

R- She’d be eighty one or two I should think.

Aye. How long ago's that?

Mrs. Platt.- Seventy three! (Mrs. Platt was present at the interview)

R - Oh seventy three. It's me that's got that wrong, she were seventy three.

How long ago's that, roughly?

Mrs Platt- She's been dead about twenty eight year now.

R - About 28 year since. She died at me sisters you know, up Cobden Street, Billy Spensley lived there, that's me sister you know.

Aye. How many brothers and sisters did you have?

R - One brother, one sister. Walter died, he came off work one day and doctor said he’d a bad cold you see so he went It’d work off but it didn't, he’d an ulcer burst that night and he died, he were dead the day after.

(200)

How old were he?

R- Twenty, twenty one, weren’t he?

Twenty one.

So when would that..

R- He died in March and he’d have been twenty one in July.

Aye.

Mrs Platt- Our Ronnie were a fortnight old when he died and he's fifty now.

R - That's right yes, yes.

Aye, so that's fifty year ago, that's going to be 1929.

R – Yes, he were Walter. And our Annie, she's living yet, you know our Annie don't you?

Aye, and how about school? Can you ever remember school inspectors coming or anyone like that? Can you ever remember anybody coming to school, you know, to see about your health or the way you were being taught. Can you ever remember anybody coming?

R- No, not them days, no not really.

Nurse looking at your hair or anything?

R- Oh I remember that, when the nurse used to come looking in your hair for the old bobblers aye. [Nits]

Jack and Stanley laugh.

R - Oh aye but we allus passed them tests like, you know what I mean. As rough as we were she kept us clean.

What age did you go to school till Jack?

R - I went half time when I were twelve and left school when I were fourteen, you know. If you hadn't enough [time in]..I don’t know why because I can never remember being off much but it went in attendances. Unless they'd put it to fourteen then.

Yes.

R- I could never grasp that but it must have been because I were never one to miss school and I never.. I weren’t one to run away. I were as rough as any other lad but I never ran away from school.

Aye.

(15 min)

So twelve year old that’d be 1917, that’d be during the war you went half timing.

R - Yes that's reight.

Aye.

R- Aye that's right.

Aye, 1905 so that’d be 1917 it’d be during the war when you went half time.

R- I went half time when I were twelve.

When you were a lad Jack, I know we've talked about this before but you know, we play hell about kids nowadays and this, that and the other, how did you amuse yourselves?

(250)

R - Well we used to go swimming, jumping, running, laiking in the quarry, you know, playing about. Raiding orchards [laughs] Getting through the bob hole in hen huts and getting a few eggs out. Me mother used to send me for a bob's worth of eggs at Saturday and it used to take us all Saturday morning rounding 'em up out of hen huts so we could have, He He, so we could have the shilling. I'm telling you this, I'm telling you facts.

Aye.

R - I mean that's how we used to amuse us self.

Aye.

R- Raiding. I once remember old Jim Sutcliffe tha’ knows, landlord at that long row at Tubber Hill. He had a big garden out back and pea-swads, you know, all rows on 'em. So, it come this night we decided it were raiding night, we’d raid him. So three on us, there were me, Harry Grimes and George Horrocks and we all raided, well we raided peas. We’d a big bag apiece and we’d filled ‘em up. A big bag like that, get 'em up ready for going and then a chap, a chaps voice came, ‘Narthen’ he says, 'You can fetch them buggers here now, it'll save me picking ‘em'. Hee Hee!

(Laughter from Stanley)

R - Eh! He were sat down behind the hut. He’d never said nowt till we’d picked ‘em! And then we’d to go and give 'em him and we daren’t but miss tha knows.

Aye.

R - Aye, I allus remember that night. And then we were raiding the orchard on Peel Whitakers, tha knows, it were Peel Whitakers farm. Tha knows, down Salterforth Lane..

Aye.

R- On that lane, half way down. That one there, a chap called Whitaker had it then, Peel Whitaker and then they went on..

Oh yes, it's Bradley's now.

R- Oh I don’t know who has it now. Aye, we went on there, it were one Sunday. I used to go on there while they were all at Sunday School. And George, tha knows, he were allus there. I liked him a lot. So he’d a hole in his top pocket, in his top coat. He had a hole in and apples were dropping through and he's up the tree tha knows. Then all at once they land back [the farmer] so we jump down but George couldn't make it see, he’d too many apples in his top coat. They caught him, he geet apples alreight that Sunday did George, his bloody coat were packed wi’ apples, Hee Hee! No, we really really enjoyed us self up there in, you know when the old ferns, bracken were in. When they were dying off we used to make what you call a bracken house.

Aye.

R - That were us headquarters you know. Oh we've been chased. Old Bird chased us, I know he once caught me and George Horrocks, he says to George "I've kicked men off here nine foot high. Don't think you’re going to frighten me wi’ using a bit of cheek! So when we set off George turned round, he shouted “You f …..g lying bugger Bird!” Aye, oh aye.

(300)

(Laughter from Stanley).

R - That were old George Bird tha knows, oh we used to..

Who were he, quarry foreman, manager?

R- Who, George?

George Bird.

George Bird, gamekeeper and his wife Mary Sharp at Craven Laithe Farm in the 1930s.

R - George Bird were the game-keeper that lived on White Moor then..

Aye, that's it..

R- Again the reservoir, you know. [Whinberry Harbour]

That's it aye, aye.

R- Aye, then he took, he took the Fanny Grey [Lane Head pub]after, Bird's you know.

Aye that's it aye, aye. And when you left school Jack where did you go working first when you went half time.

R - Now wait a minute, when I went half time? Oh Coates Mill, learning to weave wi’ me mother.

And she were weaving at Coates then.

R- She were weaving at Coates then yes.

Who had it then, can you remember?

R- Eh no I can’t remember. I can’t remember who owned it, I only remember the chap that used to reckon to be boss inside, they called him Old Nelson, he’d one eye. 'Cause that were him that… They used to put you learning wi’ people, you know, but I used to get sacked from every one on ‘em. Hah Hah! Tha knows all twist that comes up.

(20 Min)

Aye.

R- Well I used to break one on ‘em out tha knows and the old shuttles that they used to have on wi’.. and I used to thread one of them through tha knows, and they'd come up and they'd get end ready to take up and they'd be like this tha knows, bloody miles on it.

(Laughter from Stanley and Jack)

R- I get sent home wi’ three different ones at Coates and then I get sacked and I were only twelve. Anyway we went to Birds at Calf Hall after that.

Aye.

R- They called it Birds then, it were top firm. { I don’t know who this could be. I have a reference to Charlie Bird later in the 30’s}

Aye.

R- There were our Annie, me and me mother and we started and we worked there. Course I…and then our Annie had four looms, me mother had four and I were only like what you call a tenter you know.

Aye.

R- ‘cause I were still going to school.

Yes. Who paid you when you were tenting?

R- Well them that you tented for, you see.

Aye, how much?

R- Half a crown I think. Well they paid me mother, I wouldn't have getten none. And then from there, we came up here, we were one of first, some of, we were the first weavers in here.

In Bancroft.

R- I'd left school then and I were going on four loom.

Aye. Now wait a minute, wait a minute, just let's get this straight now. So you were working down at Calf Hall and from Calf Hall you came up here.

(350)

R - Calf Call mind you, I left, I left school, well I was at Calf Hall.

So that's 1919..

R- That's 1919

You'd leave school.

R- It would be, aye.

You were working at Calf Hall then.

R- Yes.

And then you came up here.

R- And then Bancroft Mill were setting some weavers on. They'd like started opening then you know. [1920]

Aye,

R - So me and our Annie and me mother all came up to Bancroft Mill.

Yes.

R- And that's where I got me first four loom.

Aye. Now just hang back a bit there, hang back a bit there because this is really one of main reasons why I wanted to come and see you Jack, because there's all sorts of people say all sorts of things about this, and I want to get it right. Now forget about going to work therefore a minute.

R- Yes.

Can you remember when they were building Bancroft.

R- Oh yes. Yes I can remember when they were building it.

Right now hold on a minute, hold on a minute. When did they start?

R- Oh now wait a minute, I don't know about that, oh no I can’t name that year. I know this, they started building that and they built it and there were a war on weren’t there.

Yes.

R- And there were a delay in opening it till the war finished or sommat.

That's it.

R - There were sommat. There were sommat happened that way. There were a delay.

Now during the war what were standing where Bancroft is now, were there any actual building done after war or was the building built. When can you first remember seeing Bancroft as a building?

R- Wait a minute. No I can’t. It runs in my memory, I can remember ‘em working on it. Yes it runs in my memory I can remember 'em working on it. Yes I can. Because we used to go to school from Tubber Hill down there you know.

Down Tubber Hill down, where were you.

Down Tubber Hill way you know.

Where were you going to school when you lived at Tubber Hill?

R- Gisburn Road school.

So which way did you come down, this way, Tubber Hill up…..

R- No straight down. Straight down the....

Yes, straight down like Barlick. Lane, Manchester Rd ..past..

R- Past the Greyhound.

That's it yes.

R- But they were building it then.

(400)

Yes.

R - They were on with it because Saturday I know we used to bounce round a time or two playing round it, you know, playing about there. Aye. And then, I’m going back a long way you know.

Yes.

R- Then it were finished and I know there were some sort of a lull in it, I allus remember that, they weren’t going to start it [begin running] till the war finished or something. Sommat like that. Because in the mean time I’d left school and been knocking about you know, Calf Hall. Bird’s at Calf hall.

Yes. Yea so as I understand it, I haven't got to the bottom of this yet Jack.

R- Oh wait a minute, no, no I've done wrong here. I've gone wrong. I didn't leave school, I didn't have me first job here I had it at Rawtenstall. I left school at Rawtenstall when I were twelve.

Aye, that's it.

R- I’ll have to go back.

When they moved back to Rawtenstall yes.

(25 min)

R- Aye, I left school and I went as a last-sorter in the slipper works. Hoyle and Hoyle, slipper works.

Aye.

R- But it were only a short spell do you see..

Yes.

R- But I’d missed that spell out with you.

That's it.

R- And that's when we come back to Tubber Hill from Rawtenstall.

That's it and then you'd go down to Coates with your mother.

R- That's right, yes.

Oh well that's right we've got it straight then.

R- Yes.

And you see I haven't got to bottom of it about Bancroft. One of the things that I can’t understand about Bancroft is that I've always been ..you know, they say that James Nutter's started weaving at Bancroft but I don't think they did.

R- James Nutter.

Yes.

R- Started weaving at Bancroft.

No but started, that they first started Bancroft up. When you went to work at Bancroft who were you working for?

R- Nutter's.

Ah now, Nutter's, but which firm, 'cause there were three firms weren’t there.

R- Aye there were three, yes there were.

There were three firms, there were James Nutters, W E and D and Nutter Brothers.

R- Well it weren’t W E & D, and it weren’t Nutter Brothers so it must have been James.

(450)

Aye. {It was Nutter Brothers actually, taken over by James Nutter Ltd when they left Bankfield in 1932]

R- Because I knew, I know them with later years, other Nutter's when I were on weft for W E&.D. Nutters. [Jack is talking about carrying weft when he was driving for Wild Brothers.]

Yes.

R- And one on ‘em used to live up there you know, that were Dick, there were Dick Nutter and another. No it’d be James Nutter.

Aye. Course James actually died in 1918 didn't he, he never saw the mill start.

R- Didn't he? No well, I wouldn't know that.

Yes, James actually died but you see the thing I can never understand is that while Bancroft. After Bancroft had started James Nutter's was still weaving down at Bankfield.

R- Yes that's right, yes they were weren’t they. James Nutter at Bankfield.

Aye and then..

R- Which shop had they at Bankfield then?

They were one of first tenants in there, back shop, they had about a thousand loom in there.

R - Had they, oh had they. And then Sagars were down there.

And then..

Mrs. Platt- Well me dad worked there for them Nutters at one time.

Where?

Mrs Platt- Didn't he?

R- At New Mill or Bankfield?

Mrs. Platt- New Mill.

R- You were talking about. We’re talking about Bankfield.

No, this is Bankfield and I think meself that there was something.. There's something somewhere about, there’s something happened somewhere about James, ..about Nutter Brothers going to start there and then in the finish they didn't.

R- I see.

And I haven't got to bottom of it yet. Anyway main thing is, main thing is that you went to work there. Now did you go to work there when they first started?

R- Yes.

You know when engine first started, can you remember what the date of that was Jack? [13th March 1920]

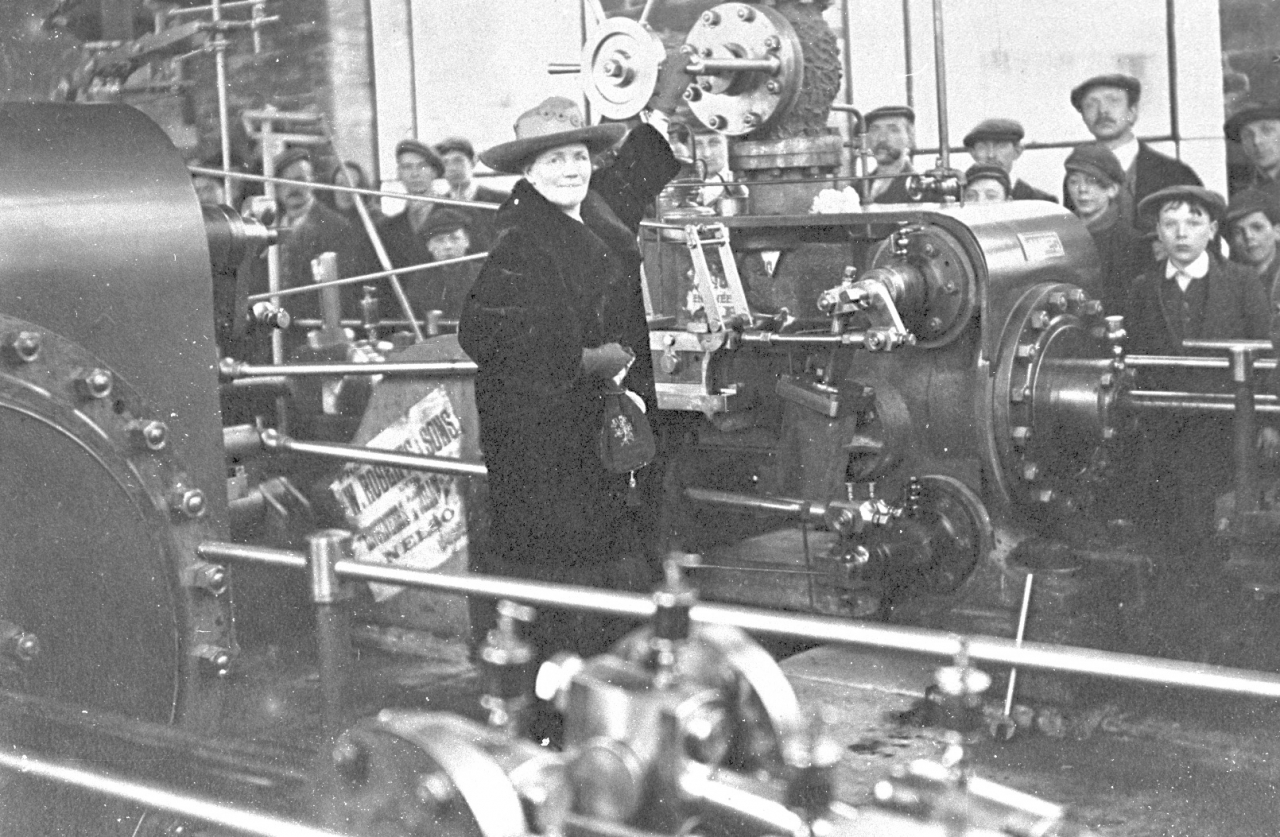

Aunty Liza Nutter starting the Bancroft engine in July 1920.

R- Oh no, no I can’t remember..

Mrs. Platt.- Well how old were you when you had your hand done..

R - Well I can remember this, that there were, that we got told when we went in if engine started running fast and running away we’d to run out, we’d to go out, leave everything and run out. They didn't pay you be what you earned, they, you got a standing wage.

Aye.

R- Because we’d to run out once or twice and once when we went back one of my looms were on top of other!

(500)

Is that right?

R- Yes, well it used to set off at t’boggart and there were only a few, twelve looms or twenty looms running.

Aye, aye.

R- There were only a few of us because we played football at tea breaks in the mill itself. They were still wheeling looms in and fixing ‘em you see.

Aye.

R - It weren’t no way finished. They'd hundreds of looms to put in when I went there.

Aye.

R- Aye. And it had, we got told very strictly not to waste one minute, not to waste no time if it started running, you know, really fast.

Aye.

R - Go out, run out. So we used to run out. In fact I run out a time or two when it weren’t really running at t’boggart. Hee Hee! Aye I’ll allus remember that once when I went back one of me looms were on top of another.

Aye picked up, belt had picked it up and thrown it up on top?

R - I worked there when that woman were killed you know, with the fire proof doors.

Ah now tell me about that. That's a story that I keep hearing and nobody's been able to tell me about it.

(30 min)

R - Well I can tell you about it because I looked at her after, when they had her laid on a table with her head in a big bunch of waste.

Aye.

R - Now her and me sister used to always go out together, they worked at side of one another. But our Annie she had, she were taking a bunch up, what they used to call 'em, or sommat.

Yes.

Bancroft weavers on the banking at the back of the mill in 1921. Left to right, Annie Platt, (Iris, Edith?) Barrett, Mary Joyce and Vera Scott. I don't know the name of the lass who was killed but she is probably one of the group as they were all friends.

R- And she said she'd follow her round. She went out and as she went through them doors, them fire proof doors dropped on her and flattened her and they were two ton were them doors they reckoned.

Aye.

R - It took enough, so many people to lift it off. Half of the mill nearly, you know what I mean.

Aye.

R- And they, I can remember as plain as now 'em carrying her to that long table they had for..

Cloth lookers?

R – Yes, it run this way down mill then, not that, under the window..

Aye,

R- ..and one down here. And they had her laid on there on a reight big bundle of waste, you know. Yes, she were killed, well killed instantly. I can remember that do. They nicknamed that place ‘grave yard’ in them days. Can you ever remember that nickname?

Aye, yes.

R - They called it the Grave Yard.

And when, what year would that be Jack?

R – Eh, heck. Aye, let's see. Well we'll go this way it, it were that year when I were sixteen so you can reckon it from there.

1921.

R- It’d be 1921.

So that’d be the year, I reckon, ..I reckon..

R- It’d be 1920 or 1921. It’d be happen when I were fifteen or sixteen. I'll not swear which, how old I were..

I think..

R- Oh no I'd be fifteen, I'd be fifteen would a..

No, oh no, now hold on a minute, your persuading yourself because as far as I know..

R- No I'm not! I'm going off having that accident wi’ me hand when I were sixteen.

Aye.

R - And I were working. I’d be fifteen.

Aye.

R - I'd be fifteen when that accident occurred.

Well that must have happened soon after mill started then.

R- Oh aye, aye the mill weren’t, it weren’t full of …

Weren’t full of looms. That's just when it first started.

R - Yes when it, aye.

Aye. Because now you haven't given me a date yet for when it started but..

R- I can’t, I can’t. I don't know it's, I’d only be guessing. 'Cause you see it's something that's gone out of me mind a long, long time ago, you see what I mean.

That's all right, I'll tell you what we'll do..

R- I've nothing to remember the year by.

I’ll tell you what we'll do, we'll quietly fetch it back in. Can you remember 'em actually starting the engine the first time, were you there when they started it or about.

R- No, I don't think I'd be there when they started it. Happen the day after or sommat. I were there the first week when they were starting, going to run it you know.

That's it.

R- And run looms.

Now were it summer or winter?

R- No it’d be good weather.

Good weather?

R- I think it would be, aye.

Aye.

R- I don't think it’d be winter. Happen, no I don't know, I don't think so.

Can you remember it being cold. You know, no heating when you first started.

R – No, that's what I’m going off.

Yes.

R- Because it weren’t cold.

So, a good chance it were the spring of the year.

R- Spring of the year aye. It wouldn't be winter because I mean, I don't think they'd have, nobody would have stuck it in there.

Aye, wi’ no looms in.

R- because it’d have been starvation in there you know.

Yes. So it nearly looks as if it's going to be, now wait a minute if it were, ..if it were 1920 you'd be fifteen year old.

R- Yes. I would wouldn’t I.

Yes. Now would that be about right?

R- Aye I reckon it would, I'd be fifteen. I wouldn't be sixteen because I'd be sixteen in May as I had this accident in July wi’ that there. No I were fifteen..

[It took us a while to get there but we got it right in the end. I should explain that at that time I didn’t know the exact date Bancroft Engine started.]

Now what accident were that.

R - When I got me hand done.

Yes.

R- That's what I’m going off see..

Yes.

R - I’d be fifteen because I'm only going back May, June, July from me birthday aren’t I.

Aye, that's it.

R- I were fifteen so you reckon it from that year.

So that's going to be most likely spring of 1920 when they started.

R- Yes. It would be an all.

Yes and you wouldn't be working there long before you had your accident with your hand.

R- Oh no, no.

A matter of like three or four month happen, something like that.

R- That's right, three, that's reight, yes it were long enough, I hated it.

Well, that's going to be, that's going to put it then, that's going to put it at spring of 1920.

R- Yes.

(35 min)

Early on in 1920 but not early enough to be cold.

R - I'd be fifteen wouldn't I?

Yes. You'd be fifteen and that’d be the same year.

R- May, June, July and then I'd be sixteen and I were sixteen when I had that accident..

Yes.

R- So I were fifteen when I were there, yes.

Now that accident you keep on about, course these tapes don't give pictures, you've got two fingers missing off your right hand. How did that happen?

R- I’ve, got three, three.

Three. Is there three missing?

R - There's nearly all the lot missing really.

Oh that's it. How did that happen?

R- Well, we were going swimming, I telled you we used to do a lot of swimming. So we're going swimming one night you know, going down Salterforth Lane and we goes through the quarry. Course if you see any open windows you, in them days you used to bob in and see what you could find, didn't you. So we went in and we found these here detonators, you know. So we like, I said, young Johnny Grimes were there, my mate so, “Eh hell, them's just right for making pencil cases on. I’ll have one or two of them.” you know, what do they call ‘em, detonators, what they blast wi’.

Mm, yes detonators aye.

R- They shove 'em on the end of the fuse.

Yes, that's it.

R- So I put about half a dozen of these here in me pocket and then we went swimming, thought nowt about it you know.

R- Anyway, when we’d been down we were coming up Salterforth Lane and I'm scratching this here bit of white stuff, bit of white, about that much, down in the bottom of t’doing's you know. I’m scratching it out when, WHAM! and it went off, blew, no messing whatever, just blew 'em clean off. I just said hell, what a bang, you know, to the lads and I looked round and I saw me fingers on the floor!

Aye.

R- And I looked, aye I did that lad, and I remember that as plain as the day.

SO now…

R- It just touched tip of that, see what I were pricking it with, see, point of that.

Aye.

R - And the tip of that, see, what I were pricking it wi’, see, point of that!

Aye.

R- Eh, can’t tha see it, tip of that and tip of that.

That's it aye.

R- Well I’d the pin in that hand see. It's a bloody good job, it could have blown us head off couldn't it.

And now, hang on. Nowadays when that happens, what you do is, you go to the nearest telephone box, dial 999 and get an ambulance, but like you couldn't do that then. So what did you do?

R- Well one on 'em must, there were a chap, I think there must have been somebody passing and they ran somewhere and I don't know how they got me home, in a milk float or sommat, they took me home.

Mrs. Platt.- They took you home in a milk float.

R- In a milk float, aye.

Mrs. Platt.- And you were laid all night before you went..

R - And then the doctor come up and he just looked at it, put a piece of wadding on about as big as that bucket there..

Aye.

R - And put it, just slapped it on and said that, and at morning they took me to Burnley in old Palmer’s, Harry Palmer’s father’s milk float to Burnley hospital, that were after a night in bed. Blood had gone reight through the bloody tick bed on to the bedroom floor, stained the floor.

Aye.

R- Aye. Tha can tell that were, that were them days of medical attention. All night wi’ that. It had gone, it were that. It were like that there padding, it had gone clean through it, through the bed.

Aye, through a foot of bed!

R- Aye.

So you’d lost some blood.

R- I had lost some blood, I couldn't stand up.

Aye. And when you got to hospital what did they do?

R- Just took me in and started telling me to try to count to a hundred and I think I got to sixty six afore I started choking ‘cause it were chloroform then tha knows.

Aye.

R- Not like it is to-day. Eh, gasping, eh, get this bloody thing off or sommat tha knows, Anyway I were a long while tha knows they telled me after, I’d 68 stitches in ‘em an all.

Sixty eight.

R- Aye sixty eight. It weren’t reight bad were it.

No, no.

R- 'Cause there were the palm of me hand and dosta know what that doctor said?

No.

R - He said, “If you hadn't have been so young" he said "I could have made a reight good job of that" he said “Because I'd have sliced it off wi’ your wrist”.

Aye.

R- He said "It’s only your youth".

Aye.

R - And he says "I'll tell you one thing". And I says what? He says “I can always put you a thumb back on” This is doctor Watson. I said “Oh can you”, tha knows 'cause I'm only sixteen. And he says “Yes, but you'll have one big toe missing". "Oh'' I says “Bugger that". Hee Hee! And he laughed every time he come past me bed. Aye he did. I'll allus remember that do.

(Laughter from Stanley)

R - I'm barn’to light a fag is it reight?

Aye course it is, aye.

R- Dosta want one?

Eh, no thanks, no, no. Aye, so you didn't want your big toe putting off.

R - I were in eight weeks there.

You were eight weeks in hospital.

(40 min)

And when you came out did you go back to the mill?

R - Oh no, that were out of it.

Yes.

R- I were a milk boy for Sandham, me and young Bobby Lambert, he's a joiner now, he has joiners shop now. Me and young Bobby. We run Tommy Sandham’s milk round for him 'cause he were allus boozing.

How long for?

R- Er .... happen twelve month. And then I went in the quarry.

You were still living at, aye well, we'll start wi’t quarry after.. We'll start wi’t quarry later, let's suck the juice out of the mill job first.

R- Aye.

So that were end of your career. You wouldn’t be reight worried about that would you, about losing [your fingers], about not being able to go back in mill.

R- I weren’t a bit worried that way. I were worried one way and still I were glad another way, it went two ways, you know what I mean. It's never seemed to hamper me, it's never hampered me a lot, I've gone on, this is the best part about it, I’ve gone on tests and all sorts for PSV's [Public Service Vehicles] and I worked wi’ a chap at the Ordnance Factory at Steeton two year and then I met him about ten year after and he noticed me hand and he said “Cor Jack, when hasta done that?” I said “When I were sixteen". He said “Well it weren’t like that when you were at Steeton". I said “It were you know" Narthen what dosta think about that?

Aye.

R- And I took a driving test for a PSV and they used to have their head through the window then, watching tha knows. They never bloody knew, they never knew no. What dosta think about that? There were only one thing that I did, that I couldn't do reight and that were fasten this shirt sleeve.

Aye.

R - That were what hampered me most, but I get so I could fasten it as quick as t’other. It's surprising what you can get to do, you know,

Aye.

R- Narthen. I could work out there wi’ anybody and they couldn’t tell that there were sommat missing.

That's it.

R- Barring they'd think I were a left hander ‘cause I shovel left handed.

Mrs. Platt.- Tell him about the grandchildren.

I never notice. Never notice when I'm with you.

R- No, you see?

Aye, I never notice when I'm with you.

R- Narthen.

Aye. I mean I didn't, I knew you had some off but I didn't know how many you had off.

R- Aye. I’m not a left hander but I shovel left handed. Well you see, I've a penny an hour more than ordinary labouring when I were a bang hander when I were young. They used to like a left hander more because he were facing t’other way instead of all being one way.

Aye that's it, aye.

R - Eh..eh. They used to get a penny an hour more did bang handers.

Is that reight?

R - It's reight Is that. I'm going back a long while but they used to get a penny an hour more did bang handers. They called 'em bang handers then.

Yes.

R- Left handers. ‘Cause you see they were shovelling face to face instead of being..

(850)

That's it aye, 'cause it's awkward when you’re shovelling out of a heap and everybody's shovelling right handed.

R- Aye, I know it is, they're throwing it at thee.

Aye, John Plummer were a good lad for that, he could shovel either hand.

R- Aye.

I never could.

R - Aye, funny that.

Aye, 'cause if me and John were shovelling coal he used to say, “Oh this in no bloody good, move over here.”

R - Aye.

And he used to go and shovel left handed.

R- Aye yes. Well see, that’s where we had it.

Aye. I'll tell you where it's handy an all, if you can fire both handed, when you're firing a Lancashire boiler in a little stoke hole.

R- Aye I dare say it is, aye.

'Cause he used to, he used to fire one, but one side right handed and t’other side left handed.

R- Well I can shovel left handed better than reight handed because you see you get weight of it on that then.

Yes, that's it.

R- I get weight on it on this wi’ only having me hand on the handle see.

Yes. That's it aye. aye.

Mrs. Platt- Tell 'em you can paper hang. He can do owt can’t you Jack, really.

R- Oh aye I never get nobody to do owt in house, I do it all.

Now when you first went down to Coates that’d be on the old system then, they'd be on piece work, being paid by the cut and what not.

R- Oh yes, aye.

Yes, now how much a cut were they getting paid?

R- well…

Roughly, I know it varied.

R- To tell you the truth I couldn't name a price. Because for the simple reason why, I were only what you call a tenter. I’d no interest in money, of what they made as long as I got my two bob or half a crown.

That's it and who ware you tenting for when you were down there?

R- Well, tacklers wife once, then I got sacked wi’ her.

What did you get sacked wi’ her for?

(900)

R- Doing like I said you know, putting thread through and letting 'em pull away, and thinking they'd ends down and see, every time she went out I'd knock looms off and then when she were coming back I'd have ‘em all running and somebody telled her. He says “He knocks 'em off every time you go out and set's ‘em on again when he sees you coming back.” So that didn’t work. Then taking that wheel off were another.

Now come on, that isn't..

R- Me mother, me mother sacked me at finish! [laughs] She said I were better at home!

(Laughter from Stanley)

R- So I used to do what you call mug about, I'd do all errands for weavers down to Hadens, they had a shop down there and..

Aye.

R- I used to spend most of me time running errands down there for 'em.

Aye.

R - You know and one thing and another.

And when you were at Coates, were you actually sacked or did you move away from there with your mother.

(45 min)

R- Well, I weren’t actually sacked, they used to just say like go back to thee mother, tha knows.

Aye.

R- It were sacking in a way, but I mean you'd no stamps or cards nor nowt like that. When you were, they’d say it doesn’t matter for coming in the morning. Hee hee.

Aye, so you, so in’t finish your mother’d move. Your mother moved to…

R- From Coates she went to Calf Hall.

So you went with her and your Annie went with her an all and yet Annie’d have her own looms wouldn't she?

R- Yes, she had, yes.

So did they sort of decide between 'em that they'd move together. They'd work together would they?

(950)

R- They worked together aye.

What did they run between 'em?

R- Eight looms.

Eight loom between 'em.

A - Yes.

Aye, so really what it’d amount to, your mother and her daughter would be running eight loom between ‘em and you'd he tenting for ‘em.

R- Tenting for ‘em aye, and running. I'd fetch weft and that you know.

Aye.

R- I come in handy for that.

Aye that's it aye. Who carried cloth out?

R - Oh me, I carried and you know.

Did you plait it on the loom an all?

R- What do you mean?

Fold it on loom you know.

R- No, when they're pulling 'em off they do that you know.

Yes. That's it.

R - And then they just put 'em on, well I used to take 'em in as they pulled 'em off, you know, I were allus there like you see.

Yes. Aye. Right, that’ll do for that tape Jack.

SCG/22 December 2002

8,214 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 79/AO/02

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 11th of MAY 1979 AT NUMBER 9 SACKVILLE STREET, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS JACK PLATT AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

[Mrs Mona Platt was present and helped Jack out here and there. Her contributions are clearly marked.]

So your mother, your mother and Annie left Coates and went down to Calf Hall and you went with 'em.

R- I went with ‘em yes.

And who were you working for at Calf Hall?

R- Bird's.

Bird's.

R- Bird's aye.

Aye.

R- It were top place, they called it Bird's at Calf Hall. B I R D S. Birds.

That’d be the new shed at the back, up to the dam like.

R- Well it were at top.

Aye, yes.

R- Top place.

Aye. And let's see what year would that be, were ... no that were afore Ernie Roberts were working there.

R- Before I left Calf Hall I got put on four looms when I bethink me self. That's why I went on four here. [Bancroft]

Aye.

R- You know, at finishing up. I’d just got another four loom.

Aye.

R - They'd like twelve, and they, you know I were like shoved on two and me mother helped me out wi’ mine, you know.

Yes. So you'd like twelve looms between you.

R- Twelve loom for three of us, yes that were it.

You wouldn't be doing so badly then, three of you then.

R- Oh no, no. That's when we started feeling us selves like.

Aye. Things’d be looking up at home a bit.

R- Yes, oh aye, a lot.

Aye.

R - Yes. There were only Walter then that weren’t working. you know.

And so now you heard that Bancroft were starting. Now you've already told me that you managed to sneak yourself into the engine house. Now tell me about that.

R- What do you mean, when they were christening the engine.

When they were christening the engine, aye.

R- Oh yes. Well you know, we came down, we knew there were sommat going on, ‘cause sometimes we went that way to Barlick. Sometimes we come this way and we came down here, I think it’d be at Saturday. [Saturday March 13th.] I think it would be anyway, so what day it were, we were coming past and we saw these here. So you know what you are when your young, you like to have a look round don't you. So we went in and up steps. There were all these folk in and in the engine house they were reading the, you know, christening the engine and that's when I got me photo took. I can see it as plain as I saw it then, Mary Jane. I think Mary Jane's at left side and James is at right. I think so. Is it?

Aye.

R – That’s reight Mary Jane, James. Aye I've allus remembered that. What happened after, we happen get thrown out, we’d happen get put out. I don't know but I know we landed outside after you know.

(50)

Aye. I've a picture of that about and there is some young lads on that photo.

C - Yes well we're among them.

I’ll show it you.

R - Because we were the only ones that were in, a few of us.

Aye, I’ll show it you.

R - Yes, aye you do.

I’ll find that picture and show it you.

R- I hope you do, I bet I'm one on 'em.

Aye.

R - And George Horrocks is another.

Aye.

R - There were a few of us, we all, we all managed to sneak in, and I think we got put out after, but they'd christened, you know they were christening the engine.

Aye. And there were Aunty Liza there wi’ her big hat, and there were no insulation on engine, there were no covers on, it weren’t finished weren’t the engine.

R- No I can’t tell you that part, you know.

Aye it weren’t finished because you could see, it were a bit of a rum job like because there were part of the insulation that weren’t on and there were still big stickers on you know… Paper stickers.

R- Were there?

Aye. Roberts, William Roberts & Son, Phoenix Foundry.

R- Aye, I never noticed that but I know..

Well you can see it on the photograph of course.

R- Aye.

That's how I know, but anyway. So you were weaving there at Bancroft and you were on four loom there, so you’d have twelve loom between you. You and your mother..

R- Me, me mother and Annie, yes.

Yes.

R- Yes, we had, we went on twelve loom, yes.

And what were it like when they were first starting? I know they’d told you about engine.

R- Well, it were rough. You see there were only what you call one box of weft in the warehouse.

One?

R- There weren’t like all these rows of boxes of weft like there is in mills. There were just one, you all went out and got it out of this one box, you know..

(5 min)

They, they kept opening others but, I mean they kept opening another after that because it were soon done were one when there were, there’d be about half a dozen of us I should think. And I know that's the first thing we got told, if th’engine started running fast, if your looms started running too fast, very fast, don't bother whatever, don't bother with nothing, just get yourselves out into the warehouse. Run out of the mill you know, run out of the shed. So we did do. It happened once or twice, but it happened once and I went back and one of my, one of my looms is like, well it were nearly on top of another loom, you know, it had bounced.

Aye.

R- Happen straps had pulled 'em up?

Yes aye. Can you remember t’names of any of the tacklers that were there then?

R- Well yes, I can remember a few names of old tacklers. There were Fred Bracewell, he were one of the reight old ‘uns. I bet Fred were one of first to start. Albert Monks, Fred Bracewell, Albert Monks. Them's two names what sticks in me mind because I used to get on well wi’ them two because we worked again [next to]Albert Monk’s wife and in fact she were next to me and they used to look after me an all. I used to like Mrs. Monks, she were a grand woman, that were old Monk's wife. Aye I should think they'd be two of the first tacklers that worked there, I should think so. I can’t remember anybody else before 'em but I can remember Fred, old Fred Bracewell and Albert Monks.

[Months after I transcribed this I learned from Sheila Wilkinson at Sough that Jack’s memory had played him false. It wasn’t Albert Monks, it was George Monks who was the tackler, he was born 1898 and so was 22 at the time. His wife was Vida, nee Collins and they were married on 1st of April 1920. The Jim Monks who was cleaning the looms was no relation. Albert had four brothers, Edward, Lapage (killed in WW1, Albert (who was never a mill worker) and Wilfred. George lived at 25 Ivy Terrace and it was his father, George Monks that was gardener for Wilfred Nutter and got £50 compensation from the bus company after he was knocked down after getting off outside the Knoll in 1929. {CH 19/07/1929} Sheila was one of George’s two daughters, her sister was called Doreen.]

Can you remember any of the other people that were working there then?

R- Apart from ours, apart from us.

Yes.

R- No.

No.

R- I've tried, I've tried to do many a time but you know they go out of your mind don't they.

That's it aye.

R- But there’d happen be about two or three, no more. And then old, can you remember old Jim Monks wi’t crutch. Jim Monks, he lives up Tubber Hill he’d a crutch.

Yes.

R- Well he used to be sweeping looms as they came in. Old Jim, you know. There were one or two men, and looms, as they brought looms in and fixed them up he were cleaning 'em you know.

He were sweeping 'em as they come in?

R- Yes.

So they weren’t new looms?

R - No they couldn't have been ‘cause he were sweeping a lot. There must have been like a lot from other mills. I should think some were new looms, I should think them were what you call 60” , there used to be some 60” inch looms.

Yes, aye.

R- And then there were some fifties, now them were old ‘uns, them were old ‘uns when they came. They'd be reight old looms, I can remember them. 'Cause I were on two of them 50”. But them 60” ones were new ones.

Aye. And, now then, I were just going to ask you sommat then ... oh! can you remember who were running the engine.

R- Well wait a minute, let me go back, I can remember two or three. I’d like to think it were Martin Grace.

Martin Grace, qualified as Marine Engineer, 2nd Class and came to Barlick to install steam powered cranes and stone cutting machines at Sagar's Upper Hill Quarries. He served at Bankfield as engineer for many years and then was asked by James Nutter to help John Waddington of Roberts Engineers to install Bancroft engine. He stayed there as mill engineer.

Yes, I think you might be right.

R- And then after him, after Martin, a chap that lived on Calf Hall Road, what did they call him, a plumpish fellow, what the heck did they call him? [I think Jack might be wrong here. I think Billy Chatwood might have been the first engineer at Bancroft. He had a club foot and his sister wove there as well. After Martin Grace there was George Hoggarth, then George Bleasdale and then SG.] ..I’ll miss his name and then, Martin Grace and then him, he lived on Calf Hall Road, I know he did. Then after him there’d be Hoggarth happen.

Aye,

R - Hoggarth and then after Hoggarth it’d be… Eh, who would it be after Hoggarth? Did him from Foulridge follow Hoggarth?

(150) (10 min)

Now wait a minute, just let me trigger you off a bit.. a little bit there and just see..

R - I can remember four. I can remember four for engine drivers there.

Hoggarth at one time had to go off poorly.

R- Aye, aye he had did George.

Aye. And somebody else took over and run it for a bit.

R- Aye that's right.

Can you remember anything about that? Can you remember anything about there being any trouble between Hoggarth and the fellow that came to run it for him.

R - Oh aye I think I can. Yes, I think I can. It runs in my mind there wore sommat yes.

Understand, I'm trying not to tell you what happened, I’m trying to trigger you off and get you to tell me.

R- Now wait a minute, wait a minute, eh there were sommat. Aye there were, I remember now wi’ George and this fellow, yes. Eh tha knows I used to know George right well.

We’ll leave that for a bit. I'm not going to tell you what it were. We'll leave that for a bit

R- It weren't wi’ him at Foulridge and George, were it?

No, it were a fellow that came to look after the engine while George were off and evidently George come up one day, before he started work again, and he didn't like condition of engine house, everything were reight mucky. And I’ve been told that sommat happened after that and I'm not going to tell you what it were. I’m going to leave you alone and…

R- I don't think I shall remember, but I can remember sommat happened.

Well you never know. Tomorrow morning or sometime it might just come into your mind. Anyway we'll leave that, because I don't want to trigger you about that because I just want to see if you… Because I’ve been told this tale and I don't know whether it's right or not and I just want to see if..

R – There’s something happened though, because now when you've tickled it off it comes back now. I can’t pinpoint it but it might just come.

It’ll come, it'll come. So it doesn’t matter, don't bother about that. These things happen, we'll just..

R- I can remember 'em now, talking about it.

Aye.

R - Aye.

Anyway.

R - I'm trying to think of that other name though.

That'll come and all.

R- But I think Martin Grace would be the first ‘un.

Aye, that’ll come and all, I’ll remind you about it, we'll come back to it.

R- And the other name’s gone but I know he lived on Calf Hall Road.

Aye. Anyway you were working there [at Bancroft] and then you had your bit of an accident. Tell me about the black powder in the quarry.

R- What black powder?

Black powder, when you laid a trail of black powder.

R - Oh aye. What do you mean? Well see..

Go on tell me about that.

R- They had this here little stone building, they called that the magazine you know.

(200)

Aye.

R- So we're up there, we allus used to be in quarry you know; bloody hell we never leaved 'em alone. So anyway we decided we’d like, we'd have a look in this little magazine. It had only a little wood door on. Anyway we soon get into there and there's a cask about of black jack, about that big you know.

Like a forty gallon drum.

R- Aye like, that's right. So we get's him out and we lays a trail about from here happen to my pen gate, down at bottom..

Aye.

R- A fair long trail of black jack.

Aye.

R- And then puts can back like open and in the hut you know.

Aye.

R - Back in the magazine and then, [laughs] goes to and near rocks then, because we lights this here match and then we jumps behind this here big rock. Hee Hee! And then all at once WHAM! it come a reight Whoof tha knows and I can just remember saying to George look at that bloody door, it's flying up through th’air, out of sight. Door and frame. Dosta know they tried for months to get to know who'd done that.

(Laughter from Stanley)

R- Because we’d had a bit of a do before then tha knows, we’d getten into the office at the quarry. There were a double barrelled gun and five cartridges tha knows. So I puts one of these here cartridges in and we goes round to see if there's owt to shoot, and there's only a sparrow, a bird. So I takes a pot shot at that and George goes and looks, he said I can’t find the bird, but there’s its bloody feathers here! He said You've blown it out of it's feathers! Well they were on about that then tha knows, we were frightened to death of 'em getting to find out about this here. Getting to know about the gun job. But as it happened it were old Sam Horrocks’ gun that had lent it Sagars.

Aye.

R- Well George were wi’ us tha knows,

Aye.

R- But I remember that little powder magazine even now when I have a walk. We have a walk round the quarry some times, I'm forced to laugh when I look up that way and see it.

Which quarry were that, top ‘un or bottom one?

R- Top ‘un.

Top ‘un aye. aye.

R - It were just higher up than where the saw mills were were the powder magazine.

Aye.

R- Aye.

Aye well I want to ask you a lot more about the quarries there. Now then, of course you had the accident with the detonators and then you went on the milk round.

R - Aye we started taking milk then, you know, for a bob or two.

(250)

Yes. And then how long was it after that, did you go from the milk round to working in quarry?

R- Yes I started in the quarry when I were sixteen.

Yes now, well you'd be like nearly seventeen, wouldn't you?

R- Aye yes. Oh aye I were nearly seventeen.

Now how did you get your job in quarry, did you know somebody that worked there?

R- Well I lived up Tubber Hill you know.

Yes.

R- And old John says, he used to see us playing about, and he used to say “I can find you a nice little job if tha wants one.” You know, wi’ it happening in the quarry [Jack’s accident] I expect, it were no fault of theirs but, and I think they were fined for not having a reight place, you see what I mean. But I think he found me a job 'cause of that. Do you see it were in Sagar's quarry.

Aye..

R - You see. Well I think they got fined a fair bit you know, for not having 'em. For not having the detonators locked away. Well we found 'em without any trouble you see, they weren’t locked away.

Aye.

R - And one day I'm on Tubber Hill and he says “I can find you a job if you want one"? I says “Yes I want one.” And that's how I come to start at the quarry and I were there like twenty years you know. [1921 to 1939, 18 years actually.]

Yes. So right, come on, when you went to quarry what did you do at quarry?

R- He pushed me on at quarry like, I'll give him his due there. Well I started like doing what little ‘uns do like, mug jobs, at first you know. And then I got learning to saw, stone saws you know.

Aye, how were the stone saws worked?

R- Wi’ a gas engine.

Aye.

R- And then I got from sawing to looking after the gas engine. It's like I said, he pushed me on a bit. And then I got moved from the top then and asked if I'd take over in the bottom shop and I took the gas engine ower and time-keeping and setting of saws.

Aye.

R - You see I had ‘em all to, I’d ask him what he wanted cutting, whether they were five inch, six inch, seven inch, eight inch, nine inch, ten inch, eleven inch up to a foot.

Aye.

R- Whatever he wanted cutting out of big, you know, out of bottom rock aye. Blocks, we called 'em blocks, you know, they were like owt to ten to twelve ton them. Just what the crane ‘ud lift, you know.

Yes.

R- And then I’d set 'em out, set the saws for cutting 'em you see. If you were cutting sixes you'd set your blades at six and a quarter to allow for the blades you know.

Yes.

R - And they'd come out six inch.

Yes.

R- And then when they were cut you'd turn 'em over flat and then if you wanted six by five you'd set 'em at five. If you wanted twelve by six same as for, you know, you'd set 'em out that way.

(300)

What were the saw blades made of?

R - Oh steel.

Yes.

R - Steel blades.

Yes.

R - And you fed 'em wi’ shot. You fed 'em with steel shot..

Yes,

R- You mixed it wi’ slurry, that’s what used to run out of the cuts.

Yes aye.

R - We call it slurry, you know.

Aye.

R - It weren’t that what cut it. It were the shot. Because if you were running out of shot, if your shot were getting low, you'd find they'd get red hot would your blades.

Aye.

R. - I've seen 'em as red as that fire, the blades.

Aye.

R - Oh aye.

Even with water running on 'em?

R- Aye there were a tap running over every one. You'd about sixty taps you know, and they swung like that you know.

Aye.

R - Across you see, there were a span. You could set 'em in-between for a long block or a short block.

Yes.

R - And it ‘ud swing it ‘ud be swinging all time. Now you'd four tubs on your stage two at each side and you were like on a stage yourself, up so as you could, you know, see on top of the rock..

(20 min)

R - And you fed out of them tubs, this slurry and shot, you see. And you fed 'em on and it were like, it were like clayish in a way but not clay.

Yes.

R- And that ‘ud wash in.

Yes.

R - Well you only mix it with this here, what you call stone dust, it were wet. You only had it with them. You mixed it wi’ them shot, it used to wash it in as the water come it washed it down the cracks.

Yes.

R- And you see your blades are on, your saws are on a swing and when it used to jet these blades ‘ud lift a touch and your shot ‘ud go under it. That's when you'd hear that noise ... ... (indescribable grating noise) you know, noise. It were the shot you know, like pellets in a gun but very small, but round shot like tapioca, small tapioca.

Yes, that's it aye. And did you use them again or did they just go through once.

R- Oh now you, when you'd finished cutting your stone, you'd pick.. you picked all that up and put it back in your feeding tub. And then like you always kept a bag on your stage, shot, and put more shot in.

Yes.

R- You allus get that, well.

So the blades didn't actually have teeth on?

R- Oh no. Once it, if a blade got sharp you'd to take it out.

Aye.

R- Because you see, if you'd set it to cut six inch and it got sharp, well it goes off then doesn’t it, it's eighth of an inch thick you know.

Yes, aye.

R- It ‘ud go off then. It ‘ud start veering, it ‘ud run out to ten inch.

(350)

Aye.

R- Instead of being six inch, you know, what I mean, it ‘ud start coming like that, well you'd to wind up then, what you call wind your frame up.

Yes.

R- And start rubbing it again from where it had started.

That's it.

R- And it ‘ud come down and you'd see a little run off at the side.

What did you do with the blades Jack. When a blade had got sharp like that, what did you do, grind it off?

R- No, turn it over.

Aye.

R- Take it out and turn it over and put it in again if it, you know, what we call ‘dogs’, you know.

Yes.

R- And they fit in and then you put a steel pin through 'em.

R- And then you, it came reight through your frame and you put a cotter pin in you know, a cotter.

Yes.

R- Narrow to large, and you drove them down wi’ a hammer, tight, one at each side.

[Jack is talking about opposing, wedge shaped cotters, a common engineering solution for making a really solid connection between two components.] You see you have to have 'em tight. So you'd to turn it over 'cause they used to like get half moons on.

That’s it Aye.

R- You see, aye.

Once they'd worn both sides that were it they were scrapped?

R- Oh that were it, you threw 'em out then yes.

Aye.

R- 'Cause a chap used to come for 'em every so often, you know.

Aye where did they come from do you know?

R- Oh they used to come by rail. Sheffield I think. I know we allus got good blades.

Aye. I have seen some of ‘em I think and they were like wavy. Have I seen some that weren’t just plain flat steel, they were like wavy, or is that how they've worn.

R- Wavy.

Is that how they've worn, you know like a bread knife is sometimes, you know, sort of wavy.

R- Aye.

I have an idea I've seen some stone saws that were like fluted on sides.

R- Oh they'd be for a different kind of thing then to ours.

Aye. I were watching some working the other day up in the Lake District.

R- They weren’t circulars were they?

Yes. This was what I were watching the other day and it were diamond tipped.

R - Aye.

And it were running in water.

R – Aye.

And that was cutting up to four foot blocks and it were circular you can tell the size of that.

R- Aye.

And by God, it could cut.

R - Aye.

And they had a saw working same as yours did but working horizontal with blades. You know, slabbing big blocks.

R- Aye.

And they were diamond tipped, they were flat blades and they were diamond tipped.

R- Aye.

And they just run water into the cracks on it and cut? Eh, the cut were beautiful Jack.

R- Oh well they are you see. You'd to feed 'em right. I’ll just point sommat out to thee wi’ this door jamb. Oh, oh we can’t.

Aye that’s reight, aye.

R- With the door jamb, so if tha can come. This is what I mean.

(Pause) [At this point we disconnected the microphones and went to look at the finer points of stone sawing on the door jambs of Jack’s house which came out of the quarry where he worked.]

So, so you were working on the saws. Now if you, obviously when you start, you saw a piece of stone in quarry and you're sawing it out of a big block. The ends aren’t straight. You're just sawing 'em off and they'll have rough ends until you've faced it. You'll like face four sides of it and it’ll have rough ends and then you'll cut it to the length that you want for the lintel or jamb or whatever you want, won't you.

R- That's reight aye, that's right. Well you see, the rock getter does all the cutting. [Of the blocks]

Aye.

R- The man up in the rock you know. Same as if you wanted an exceptionally long length, say a twelve footer, you'd go up and ask him to get you one.

Aye.

R- You know a twelve footer, well he’d have to get one about twelve foot, well we'll say ten foot. He’d have to get one about eleven foot then, that's to clear your ends you know.

Yes. What were biggest sizes you cut up there Jack?

R- Er, twelve foot. Not many, but there were twelve foot. I should think them jambs ‘ud be as high as owt that were ever cut, you know in a way.

The normal run of things like, they'd be like, well they'll be eight foot like, would they?

R- Aye they'll be eight foot.

R- But I’ve seen 'em fetch 'em down you know, you can get a twelve or fourteen tonner on you know, on them, they'd bogies built especially for it with solid wheels you know.

Aye.

R- Like little train wheels, but solid.

Aye.

R- And then you see you’d a damn big lump of rock, happen about eight or nine or ten ton sunk into the ground at the back of your saw wi’ a bloody line on as thick as your wrist nearly. Well you used to hook a pulley on there, and then you used to run your wire rope under your, you know, under your saw, round your block, fetch it back and then you see it ‘ud pull it in.

Aye.

R- You know as you were winding up with the power crane on. You allus had a crane on the bed you know.

Aye.

R- On the saw bed and that used to pull it in and out,

Aye.

R- It were all crane work like.

Aye. You'd get used to shifting big heavy weights up there.

R - Oh aye.

And how about accidents up in the quarry Jack, were there many?

R- Oh aye, there were some bad accidents. Aye. chaps allus Said like, I didn't see this but they allus said, it were before I started. They allus said that one chap that used to be rock getter up there, that what did my hand, these here little things they used [detonators] to just put 'em on end of fuse, which a fuse ‘ud just fit in ‘em.

(450)

R- Fuse and nip 'em to wi’ his teeth.

Yes,

R- But one day he nipped, he were nipping one, and he hadn't a head like then.

Aye.

R- He nipped one to many.

Aye.

R- I've heard th’old quarry men talk about that many a time.

Aye, I've heard about that happening,

R- You'd allus to be careful wi’ 'em.

[I’ve had a bit of experience with explosives and what Jack is talking about are the original Nobel blasting caps which were in use until about 1930. The primary charge was 90/10 or 80/20 mixtures of fulminate of mercury and potassium chlorate. Whilst these were a great improvement on early blasting caps, they were still very dangerous. Excessive heat or impact could initiate them, this was what happened to Jack when he blew part of his hand off. His body heat plus scratching with a point was sufficient to initiate the detonator. The ‘Black Jack’ he mentioned earlier was black powder, a refined old-fashioned gunpowder. This is fairly stable but very flammable, it will only develop explosive force when initiated by flame if it is in large quantity and confined so that pressure can build up. The detonator is used to initiate a true explosion in the black powder by means of a shock wave. Black powder is still used as a secondary initiator for modern commercial explosives which are very stable. A detonator initiates a black powder charge which in turn initiates the main charge.}

Aye,

R- Well, after it did that wi’ me I believe it because there were no flames about wi’ us that day. It were heat, wi’ going in the canal and the heat of my body. Doctor could only come to the conclusion it were that what did it.

Aye. Aye well, they were fulminate weren’t they?

R- Aye that’s reight.

Aye and it's funny stuff is fulminate!

R - And there’s only that much in the bottom.

Aye.

R – Yes, gelignite, you know that?

Yes aye, fulminate of mercury.

R - Aye.

Aye.

R - So that's the only conclusion they could come to.

Aye well Hardisty got blinded up there didn't he?.

R - Oh well, that should never have happened.

Aye.

R- That shouldn't have happened. I’m saying no accident should happen should they, but that shouldn't have happened.

Aye.

R- Because it were against the rules of the quarry, it were against the rules of everything. There should have been somebody there not to allow them lads to do it. I don’t, I mean you've to know the rules and I don't suppose they did but it happened to me twice in me quarry career and I were there twenty year. If a shot fails like that you've to come home for twenty four hours. You leave everything for twenty four hours, you haven't to work near it.

Aye.

R - And then twenty four hours after you go on and the rock getter drills as near to it as he can. But knows that he isn't going to go into same hole. Say about that far. [Indicates 9”]

Aye.

R- Straight down and then set another explosive charge off you see. Now you see when they're drilling you know, there's two lads tapping. He's sat down is the rock getter wi’ a big rock drill.

Aye, a star drill.

R - Like a, chiselling away, you know what I mean.

Yes.

R - And he's turning as they tap, 'cause I've tapped hundreds of hours. When you start at first they put you on that job. And then they get all this here shale you know, from in between beds of rock, you can knock it up into like putty if you’ve noticed, shale, good shale.

Yes.

R - And they’ve to ram that jam tight, make it air tight you know into your powder hole after you've put your detonator in and your powder you know. Now if that misses [misfires, doesn’t go off when the fuse is lit. Sometimes called a ‘hang fire’.] you haven't to try nothing else. It missed you know and then they gave it an hour and then went up and drilled at side of it. Started drilling and it went off you see. It could only have been just a delayed fire.

(500) (30 Min)

R- Aye it should never have happened. It shouldn't have happened to that poor lad shouldn't that. Course it did do, accidents do. I think he got in to trouble a bit did Edgar about it.

What did they use?

R- I don’t know whether he ever got his compensation or not. Because he said he had nowt did Edgar, but it’s to be hoped he did. [Edgar Sagar was the son of John Sagar and lived at Eastcliffe on Tubber Hill which was built for him by John Sagar. John ran the quarries and I think he leased them off the Gledstone Estate.]

What did they used to use, did they use gelignite or black powder or what?

R - Well they used what, we allus called it Black Jack. It were like crystals, reight little, small.

Aye.

R- And them detonators.

Yes.

R- You see they’d put your detonator in and then ram it with powder and then shale.

Yes.

R- It used to shift some rock you know.

Aye.

R- Cor blimey, I'll say it did! Aye, it used to fetch pieces off. Loosen ‘em off the bed and split ‘em up. Well, as big as this house nearly you know. Oh it ‘ud shift it.

What else were they turning out up…

R- 'Cause they'd go five foot down you know.

Aye.

R- Well I mean it has to shift sommat when it's down there.

What else were they getting out up there Jack besides jambs and cills.

R- Besides cills and jambs and..

Yes.

R- Everything that you build houses wi’.

Aye.

R- You know, cills, jambs and you know, door steps, door jambs, window cills and jambs. Oh there were points that were for building jobs

Yes.

R - There were pavings for roads. They did a lot of that because they used to send two boat load away a week you know to Burnley.

Aye.

R - They'd two boats you know Ida and Alice, they called the boats after the lasses. Because when I were driving at first on the quarry, when I started driving, that were through our Annie’s husband you know, I allus used to be wi’ him. Well they bought a new wagon and they put me on the old Dennis and we used to take a load of setts to Burnley, to the top of Manchester Road, they were like on paving jobs then. A lot of pavings. And then we used to have to go half way down Manchester Road to the canal wharf where the boats landed and we’d empty the boat then. Well we’d be reight for two or three days then you know. Well we’d be reight for three days, but taking one at morning mind you, coming home at night and then taking another load and then back to the boat. And then two boat men used to help you and you'd cart 'em then from half way down Manchester Road to the top of Manchester Road do you see. Till you'd emptied the boat. Well you know, there were fifty ton in each boat, like that were hundred ton weren’t it. And Hartley Barrett and Oates Barrett from Foulridge used to be boat men.

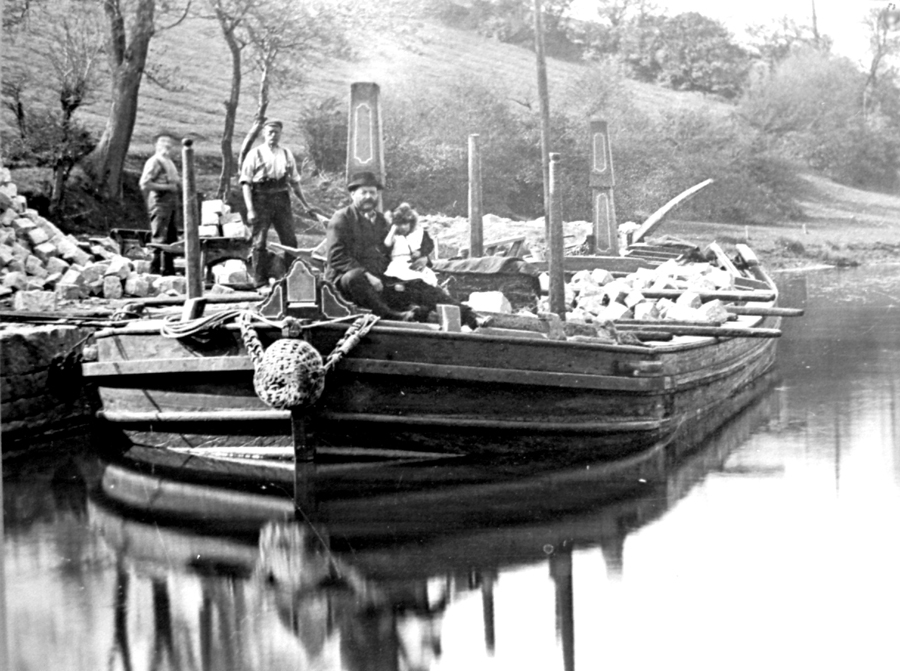

Park Close quarry had a similar boat. Here it is loading for Burnley. {Later research suggests that the man with the child is Witham, the quarry owner.]

Hartley and….?

R- Oates. They called him Oates.

Aye.

Oates, Hee Hee, he’d had his oats an all had Oates. Two grand fellows.

R- Barrett, his son is still on the haulage job yet, now.

Aye.

R- Walton Barrett that's his son.

That's it.

R- That's his father I'm talking about and his fathers brother, uncle Oates. They’d sleep in their boat then you see.

Aye that's it. Aye.

R - Well we had us meals in the boat, I used to like it, that job.

Aye.

R- In the cabin at dinner times tha knows.

Aye. And when you were working up here, obviously they’d have gangs on cutting setts out and what not and dressing points and what not. Were they paid on piece work or were they on day work or what?

(35 min)

R- All the banker hands were on piece work. All what you call banker hands.

Yes.

R- The rock getter weren’t. He were on by the hour. Hourly pay, but all the banker hands were on piece work.

Yes.

R - Sett makers, point makers. They were all the same men do you see.

Yes.

R- Some ‘ud be making points, some ‘ud be making setts, it just depended what job were going on at the time.

Aye. And they'd have a smith there would they, sharpening tools and what not.

R- Oh aye they’d a blacksmith in each place.

Yes.

R- There were Scotch Bob up there and if they hadn't one down here, he’d come from the top, you know, mornings - afternoons and vice versa.