TAPE 78/AB/3

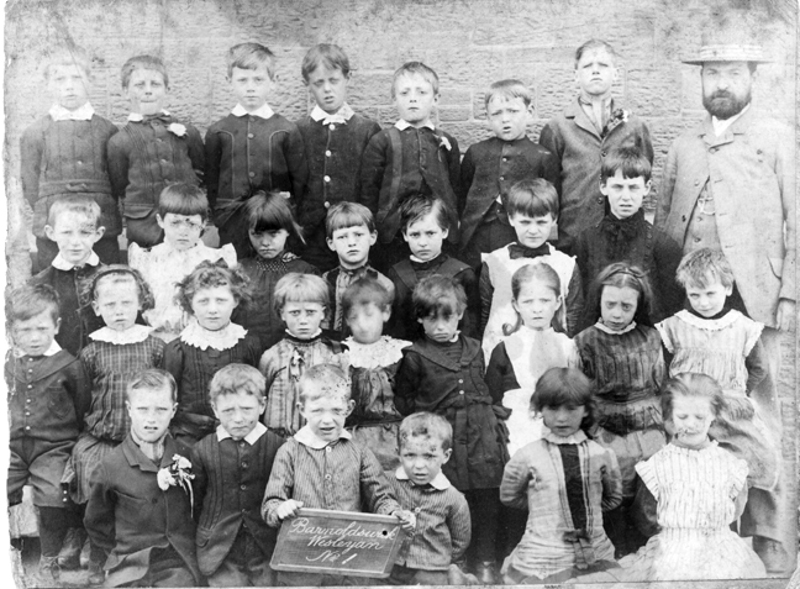

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 25TH OF JULY 1978 AT 17 CORNMILL TERRACE, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS BILLY BROOKS AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Now I’ve been thinking a lot about what you were saying during the week and I was talking to Newton and I told him that you said about there being an engine in Old Coates Mill because he weren’t sure. You said something else that interested me Billy. You were saying that at Clough Mill you remember seeing a beam engine in there.

R-Yes, I can tell of that.

Can you tell me about that, because you were telling me the name of the engine driver as well.

R-It were Mark Brown at that time, I remember, there might have been another after, I don’t know but it were Mark Brown and he lived on Rainhall Road, I can tell you th’house and his son and I went to school together, we were in the same class and he used to say to me Come on, let’s go and see me father up at Clough, and we went up and we waited until he stopped and then we come home together. We went many a time there, aye. [Billy’s recollection fits in with what we now know about the engines at Clough(December 2000). The Furneval engine was installed 1879/80 and though it started and replaced the old beam, this was not taken out because we know from the GS information about the Cotton Times report of 1891 that they tried to restart the beam to replace the Furneval which was obviously uneconomic. This coincided with disputes about pay in the town due to the manufacturers trying to extend the terms of ‘Local Disadvantage’ so we can safely assume that the trade was tight and margins were low. This attempt to switch back to the old engine failed because the beam engine was ‘too tight’ but it seems obvious that they did succeed because the mill ran until 1913 before the new BI engine was installed even though the Furneval was sold to Whalley in 1900. So we can be certain that Billy was right, the beam was in place during his schooldays and if he is talking about when he was nine or ten years old he could have seen it working.]

And that were a beam engine were it Billy?

R-It were a beam engine. I know just where it were too but of course it’s pulled down now. It weren’t far off the boilers, it were just at th’end o’t boiler house where it were situated but of course it’s pulled down now you know, aye. But it were Mark Brown, aye, Mark. I can, they lived on Rainhall Road, they’re made into shops now you know, about third round t’corner they lived, there were Willie Brown they called the lad, he were th’only lad they had, aye. And Mark used to be washing hissel’ you know, ready for stopping it, so he could just shut t’door and off you see. [All the small shops at the start of Rainhall Road from Newtown were originally built as cottages, same as on Albert Road]

Aye, that’s it. So it didn’t tek a lot of stopping then?

R-No. Well he did t’firing an all you know. I don’t remember a fireman. I remember a fireman in after years, one o’ Demains did it. Well of course, I’d a granddaughter who worked, wove there a bit and I once went in and it were one o’ Demains, he might be dead now, aye. He were, …. But I think them other engine’s were put in then you know, I don’t think that beam engine were in then. They were them under that tank weren’t they, there were a tank up at t’far…. Well, I think they’d be under there wouldn’t they, them engine’s that were put in. They’d be horizontals wouldn’t they, aye.

How old would you be about then Billy?

R-Well, when Mark, when I were going to school, we’d be about eight years old.

Aye, so that ud be about 1890 then?

R-Aye it would be, yes. We went to school together, aye. Yes. I can tell on it as plain as it were yesterday, aye.

Something I wanted to ask you from last week Billy. What were your father’s name?

R-James Brooks.

What was your mother’s name?

R-Annie. Annie, but her real name were Anna but they allus called her Annie. Her maiden name was Watkins and she come from down in Hereford or down that way. She had a brother lived down there who were a farmer and she had a brother at Wem in Shropshire called Tom Watkins.

How did she come to be up here Billy?

R-I don’t just know but she came to live up Town Head somewhere, up opposite, what do you call the house , Old Billycock’s?

Newfield edge.

R-Newfield Edge aye, she lived somewhere up there wi’ a couple. Like, they kind of adopted her in a way, called Chadwicks, aye. He were a mason and they went to Southport into a guest house after that did that couple. Now she gets married to me dad do you see, aye. And she were a red-cheeked lass you know, healthy, and she had eleven children. I think I get me good health off her ‘cause she were nobbut about twenty one when I were born but of course I, I nobbut heard about it as I got to know her, she allus had red cheeks and …. Aye.

Aye. Your first job when you left school Billy was down at Long Ing Shed wasn’t it? Can you remember any of the names of the firms that were in Long Ing when you started? Who were weaving there?

R-Yes. [Billy had misheard me and starts talking about individuals and families who worked there.] Well aye, I could name a lot, aye, I could name a lot. There were Dick Wilcock and his wife and son, Joe Wilcock and he’d either one or two daughters. I know where they worked when I were tenting for that chap, they worked a bit lower down, aye. And then there were Bob Cryer and his wife Bella who I tented for. At one time there were Jabez Soni(?), he finished up as a bookmaker and I think he were in a car accident or sommat. Oh, I could go round there, There were Tillotson’s family, Bill Tillotson, they called him Bill Gads, Gads aye. Well there were about three of them, they worked there.

Was it usual for a family, when they were weaving in a mill, was it usual for them all to weave together, like beams to each other?

R-Yes. Aye, nearly , they nearly allus worked, odd times they couldn’t just manage it you know, but mainly they were together. Aye, there were the Tillotson lasses, they had, there were a ten loom alley and a right old loom me uncle got me and another lass [when we were] half timers for two middle looms and there were four at each side, aye. And then there were an old Barlicker called Maggie Barker, she married Jim Thornton at t’finish in later life. And there were old Bill Pollard. Jim Dux, they called him Dux, he lived at the back of the Commercial where that booking office is [bookmaker, betting shop], he lived there did Jim Dux and he had two lasses and they all worked there. And then there were Preston Jimmy wi’ two daughters, they called him Preston Jimmy, he come from Preston, he must have, ha ha! They all had a nickname you know had Barlickers in them days. Aye.

Did you have a nickname Billy?

R-Nay I don’t think so, no. I were like a bit young in them days. Aye, Jim Dux, well that weren’t his name but they called him Jim Dux aye.

Who were the firms that were in there then?

R-Robinson Brooks.

How many looms did they have?

R-Brooks? Four hundred and twenty one.

And who else was weaving at Long Ing then Billy?

R-Well, there were Ormerods, Slater Edmondson’s, Boocock’s and later on Jim O’Kits, Jim Edmondson, Jim O’Kits aye. There were 1200 looms up that side, it were built for 1200 looms but they built an annexe for Brooks two year after it started, in 1890. Long Ing were built in 1888 and them engines were put in by Yates and Thom from Blackburn [W&J Yates actually. Yates and Thom didn’t amalgamate until later.] for twelve hundred looms and they spoilt t’job wi’ shoving another four hundred and twenty on to ‘em, it wasn’t made for that. [This was the extension built for Brooks]

You said it was oil lamps down there was it?

R-Aye, at Coates.

Oh, at Coates. What was the lighting at Long Ing?

R-Gas, ordinary split burners, th’old fashioned split burners. Aye and t’tacklers used to go round wi’ a lamp wi’ oil in and some holes in it and they used to touch it you know [the oil lamp] it used to smoke up, it filled th’hoil wi’ smook, aye. Ha ha ha! Aye it did. They were waiting on ‘em turning t’gas on you see wi’ them lamps, they were smooking, it were loom oil that they had in ‘em you know, wi’ wicks on and they just used to go round and touch ‘em you know. And then there were a manager at that time after me uncle Willy had died (William Brooks) [the new manager was George Brooks] , he used to turn the gas on and you know there were a handle on it. It were one of them with a mark across you know, [What Billy is describing is an old fashioned plug cock that turned 90 degrees to be fully open. The mark he talks about was a line scribed across the top of the cock which corresponded with the hole through the plug. When the line was aligned with the pipe the cock was fully open, when across the pipe it was closed.] He used top turn it reight round and then he turned t’damned lot out you know and they’d to light ‘em again, aye, he did that regular! (Laughter from both) Aye he did, George Brooks they called him aye, instead of going back you know he turned it reight round you see and he’d shut it off and they’d all went out, they had to go round again aye. (More laughter) That happened many a time.

That ud be towns gas Billy?

Oh yes, it came from here. [Billy’s house on Cornmill Terrace was alongside the gas works.]

And just to get it straight, you started your working life, you started weaving at Long Ing Shed.

R-Aye, half time.

Yes, and then in between, before you actually started taping, did you go to work at Coates Mill for a bit?

R-No, you see when I come to be (13) I’d four looms then and when I come up to sixteen I started going up to me dad at mealtimes and owertime at night and I gradually learned you see and then I used to do owertime for him when I got to be about seventeen and eighteen. I used to do owertime and he went home do you see. When t’Barlick holidays were coming, about a month before, he says Robinson, (that were’t boss) He wants us to keep warps in so’s folk can addle a bit for’t holidays and he says we can’t do it unless there’s owertime. He says If you’ll do a month’s owertime while about eight at night I’ll gi’ thee a pound. So I got a pound for that. That happened many a time and he gave me a pound. Well, it were a pound in them days. Well you know I went to Blackpool for a week, I used to raise about four pound to go wi’ tha knows, aye.

Aye, I remember you telling me that a feller called Thomas Henry taught your father to tape.

R-Aye, well, he were an Earby chap and he come to start for Brooks and then he were going to start for himself at Earby along with one or two more Earbyers. I don’t know what company they called it but he went to Earby so of course he learned me father to tape you see. Robinson Brooks, [was helping Jim to get on] you see me father had, he were tackling but he only had a little set of looms, it were split up that way you see. Well he had a big family coming on you know and him and Robinson were full cousins so he were like helping him on that way and he said we’ll get thee learned to tape you see, aye, so that’s how he started. That’d be about 1892 when he started alearning [sic] to tape. I think Brooks had been going [at Long Ing] about two years then when this Thomas Henry wanted to go back and start for theirselves.

How big were a tackler’s set then Billy?

R-Well, there were about four tacklers for 421 looms. Let’s see, there were Tom Smith, Wilson Horsfield, Matt Horsfield, well, there were three tacklers, I don’t know whether there were three or four I forget now.

Well, there’d be three and your dad wouldn’t there?

R-Aye, that’s right, aye.

You say that your dad only had a little set, how big was his set?

R-Well I think he’d have about eighty looms or sommat like that you know. Seventy or eighty.

Would those looms that were in there, would they be plain looms or were there some motion looms as well Billy?

R-They were all plain 38” Coopers and 40’s and 43’s that’s what they were. There were seventy Pillings looms that were made at Primet Bridge at Colne wi’ John Pillings that were brought out of Clough where they [Robinson Brooks] started wi’ ‘em. In later years they took ‘em out and replaced ‘em wi’ Coopers, it were a shame, they were good looms and all. They break ‘em up wi’ a hammer in’t warehouse and put some [more in]. It were all two up and two down, you know, plain, two up and two down.

Aye, that’s it, four shaft. When a company moved Billy, I mean Brooks started at Clough didn’t they. When they moved from Clough to Long Ing, who moved their looms?

R-Well I can’t say. I don’t know.

Well, during your time Billy can you remember seeing looms being moved about the town, you know, from one shed to another?

R-Aye, it were Herbert Hoggarth. It were Herbert Hoggarth that moved ‘em nearly all, he died about six months since, he lived on Kelbrook Road. It were Herbert Hoggarth, they were Salterforth folk and I think he had a brother that were’t engine driver at….

That’s it, George Hoggarth.

Hogarth's shop on Wellhouse Road after Gissing and Lonsdale bought it. They had taken over Brown and Pickles and the clock on the top of the building is the one that Johnny Pickles made as a memorial to his old boss, Mr Brown. When the chapel was demolished he took it back and installed it at Wellhouse works and from there it was moved to Gissings after the takeover and demolition of the Wellhouse works in 1985.

R-Aye well he’d be dead long afore. Well Herbert Hoggarth had that mechanic’s shop on there [Wellhouse Road] Gissing and Lonsdale bought him out. Well he did all the shifting when they were doing that shifting during that period you know. And they were getting rent for nowt. Twelve months for nowt wi’ power you know.

That’s interesting Billy. That’s something I’ve been told before, that the shed companies would give somebody say three or six month’s rent free to get ‘em to move into a place.

R-Aye and they paid for the flitting of the looms. Aye they did.

And I’ve heard people say that many a time firms would move from one mill to another just to get the free rent.

R-Well, it’s reight, you could, it nearly made you think so. Well, Brooks, when they built Westfield Shed, they formed the Westfield Shed Company. Now there were [the shareholders] Robinson Brooks, there were Billycock’s daughter and then Fred Harry Slater, there were three of ‘em. Now we all, Brooks had nine hundred loom and they let 400 off to Whiteoak you see. Now Whiteoaks must have flitten to Salterforth or sommat and they [The Westfield Shed Company] flit some new tenants in [According to Worrall for 1939 it was Procter and Company with 406 looms] and allowed ‘em twelve months free rent. Well, Chris Brooks didn’t like the idea of that, he said that they should have been allowed a bit of sommat when other firms could do that. But they were outvoted two to one and told he was entitled to nowt because he wasn’t flitting. The rent had been allowed solely to get the new tenant in. You see Billycock’s daughter and Slaters had two votes and Brooks only had one so it didn’t come off. Well, we’ll flit then [Brooks], we’ll flit, because they’d get free rent up at Calf Hall you understand me. Well, now then, Wilfred Nutter took the room [at Westfield] and he wanted to rue [give backword] did Brooks but they said it’s too late we’ve signed wi’ Wilfred, so Wilfred got moved in from somewhere, Bankfield I think or somewhere for twelve month for nowt.

In Westfield?

R-Aye, to Westfield you see.

Yes, what date would that be Billy, any idea?

R-Well, let’s see, that would be , well it’d be about, war started in 1940 didn’t it, well it ‘ud be about 1938 as near as I can tell you, about 1938 aye. Because t’war started about a year after they’d been up at Calf Hall. They’d got their looms flit up to Calf Hall and twelve month for nowt. Well now, the Rover Company took Calf Hall over then you know. Now then, when Wilfred Nutter’s lease were up about twelve month or whatever it were, they [the WSC company] wouldn’t renew it, we want you out and we want to get back, aye. So they get back into Westfield because in the meantime they’d bought t’others out and were sole owners of Westfield then were Brooks. They bought them shares of Billycock’s daughter and Slaters and so they said out you go, aye, they got back, aye.

Aye. How many pubs were there in Barlick in them days Billy?

R-Same as there is now. There were Foster’s Arms, Railway, Commercial, Cross Keys and t’Greyhound, aye, just the same.

Aye, and the Seven Stars?

R-Oh aye, Seven Stars.

When you were a lad Billy, and you were living on Newtown, was Newtown paved? Was it setts or were it a dirt road or what.

R-Well it were a limestone road and there weren’t a roller or nowt, but it used to get trodden down, I don’t know however it managed. We had cart ruts for a while you know, that’s all. [I think Billy might mean stones laid like a track for cart wheels to roll on.] And in after years they paved it wi’ them little square setts. Now they were like a new invention but they turned out to be slippery or sommat down that bit of a hill so that they covered ‘em over wi’ asphalt for a lot of years. Well, when they were doing the road a while back they uncovered ‘em.

That’s it yes. That’s what made me ask because I saw them when they uncovered ‘em.

The setts in Newtown revealed by road repairs.

R-Aye, well I can tell on ‘em putting ‘em down. And they were considered, like some, and they did Station Road t’same way frae Railway corner down to the station. They did that wi’ the same sort of stuff at that time, but they abandoned ‘em. It were slippery. Aye, they used to slip on it you know. When it were frosty weather it were terrible you know. And wet, even when it were wet weather. Well, it made a good bed for them chaps [for the asphalt] They left ‘em in where they were you know when they did Newtown about two years since. I telled a chap that were doing it, I says I can tell on ‘em putting them in. He says Can you? I says aye. [The original setts that Billy is talking about were small granite ones and must have been imported to the town. The later sandstone setts from Tubber Hill quarries were better because they gave more grip. I have been told that the workers who laid those first setts were French and the pattern they laid was fan-shaped. They called that pattern 'Durex'.]

Was your grandfather a Barlicker Billy?

R-Aye yes, well no, no, his father [father’s father] were a farm hand and he were a bit of a scapegoat so he were always missing you know and me grandmother lived with me uncle [great-uncle actually], him that were t’manager you know. [At Robinson Brooks] Well, she didn’t know where her husband were you know, he were more like a tramp at that time aye. He lived in Yorkshire somewhere and he died and me father went to his funeral somewhere over by Grassington, over that way. He were a farm hand you know, he’d work for different farms, he weren’t a chap that ‘ud settle down into a home you know, no, aye.

Do you think there were many like that then, that couldn’t settle down Billy?

R-There were. There were part knocking about like them. They were t’same as tramps. They’d go and work for one farm for a bit and then they’d flit to another. If they got stalled of one they wanted to be off to another, they were tramps you know. Aye, at that time Irish men used to come over for th’haytime you know. They used to come to the same farms every year frae out of Ireland and then they’d move down [the country] for the harvest you see. There were one up at Coates, I were there three years and I used to watch ‘em out of the window you see, it were the same chap that come I could tell him, he wore a cap, I thought hello, he’s landed again. Aye, I could tell t’same chap when he come out frae Ireland. [In the 1950s the Irishmen still came for seasonal farmwork at haytime and I can remember farmers complaining then that the price for an Irishman had gone up to £50 for a month.]

Where did you see him from Billy?

R-Frae out of Coates windows.

Coates Mill?

R-Coates mill aye.

You worked at Coates for a bit then?

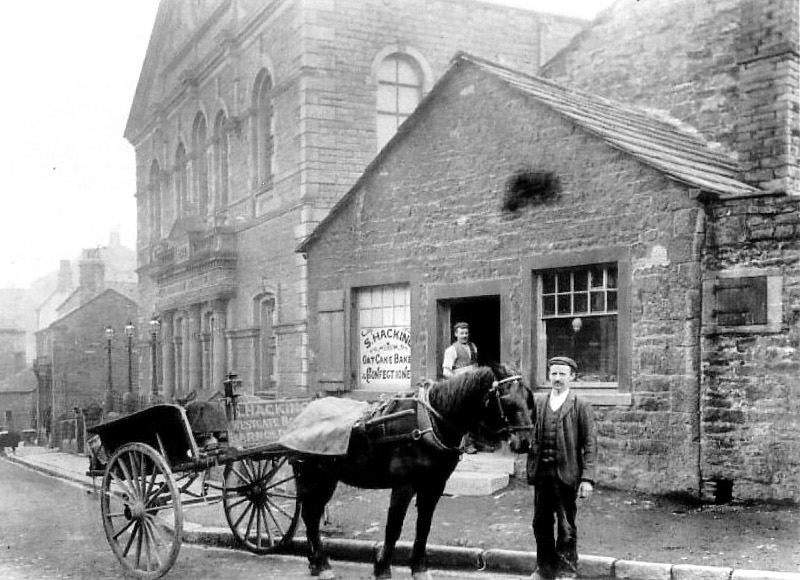

R-I worked three year, I went, there were a taping job got to let and I got it and I were there three year. I’d thirty eight bob a week standing wage. I’d started at thirty two bob. They said we’ve paid thirty eight before but you haven’t had a machine before so he says How be if we give you thirty two for twelve month and then we’ll rise you? I said Aye. Well it were a lot , it were a good wage to me were that , every week bar th’holidays ‘cause there were nowt at th’holidays and no stamps to pay nor owt. I’d thirty two bob and then at th’end of twelve month they put , I never said owt but they put it up to thirty eight and then in another twelve month there were a Mark Hacking starting at Barnsey and he wanted me to go wi’ him but I didn’t want. He wanted me to start again at t’bottom you know. He said How will it be like if you…. I thought I’ve done that once, I’m not doing it twice. So they must have heard that Hacking were [after me] so he come to me did Walter Wilkinson and I says No, I’m not going. He said Well, we’ll give you two bob of a rise, that’s two pound. Well, I didn’t think much about it but when I look back it weren’t too bad. It showed they wanted you to stop, aye. So I get two pound a week aye.

Who was Walter Wilkinson?

R-He come from Earby along wi’, they were Earby chaps, there were Hartley King and him and another or two and they took Coates over off a chap called Jackson, they called theirself, they went back to Earby and they called theirself Seal Manufacturing Company at Earby. [Named after Seal Croft, a small piece of land in Earby near Albion Mill.] So I started for a new firm that were bahn [going] to take over just afore they went you see. I did three year there and t’wife, my wife, were beaming for happen twelve month [Billy was married in 1905 so it makes his dates at Coates as 1903/1906 approximately] at t’other side of the room, I used to set her clock for her, you know, for t’length. And then they give over buying cop twist [and went over to] ring twist, beams you know so like they stopped winders and they used to buy ‘em in ring beams you know, aye.

Is that where you met your wife Billy at Coates?

R-No, she come from Barrow [in Furness] and there were no work in Barrow for lasses, they all had to go out to service and she were at Gutteridge Farm, towards Gisburn. She were there and she had five bob a week as a servant and she’d to milk and do all sorts, she’d five bob a week. Well she used to come in with Mrs Crook wi’ rabbits, they used to shoot rabbits ower theer, used to bring rabbits into Barlick and she came in a horse and trap wi’ her, there were no motors, no nowt you know. And she let her, or somebody in Barlick [let her know that] they wanted, Mrs Hopkinson, old Jack Hopkinson’s widow, she were a bit of a cripple and so she went there, she left Crook’s farm and went up Park Road and looked after the woman you know. That’s where I met her, aye.

What year would your wife move out of Barrow?

R-Oh well, she’d be about 19 year old, aye. Her sister had been at Malham looking after an old woman called Mrs Dawson and she wanted to come back home and look after her mother and father, they all worked in steel works and so she got my wife to go wi’ this woman in her place but my wife used to say wi’ living in Barrow and she were nobbut 19 she said she used to lean on the gate of a night, dark night, and nobody about you know, thinking about Barrow and all. So she left and come to Harry Crooks so’s she could get into Barlick.

What was your wife’s maiden name Billy?

R-Elizabeth Ainsworth

Aye, and so she were beaming at Coates while you were taping.

R-She were aye. Beamer give ower, he were bahn to give ower, it were Matt Holden, I don’t know whether you knew him or not. He were giving ower and so, me wife were winding then, so Walter Wilkinson said how would it be if Matt’ll learn thee to beam so he did. She took hold so Matt left and me wife did it for twelve months.

You wouldn’t be married then would you Billy?

R-Oh yes, in 1905, I were about 24 and my wife ‘ud be about twenty two. We’d get a lad then, he used to come up, me sisters used to bring him up into the tape room you know and he’d be running about and old Kit Cryer that used to work at Coates at that time, he come up one day and he said If tha can make ‘em like that, tha wants to mek some more. Aye, he did.

[Laughter] And how many did you end up with?

R-Well, t’wife were pregnant again about two years after and I went wi’t Territorials for a weeks holiday, it were t’only way, I couldn’t afford nowt no different. So I went for a week wi’t Terriers and she were only about seven month. I said will you be all reight? And she had it while I were away, seven month. And it died at two days old. If they’d have been the same as they are today it ‘ud have getten into an incubator and they’d have brought it on but there were nowt of that then, no, else they’d have getten it, you know, put it in an incubator and, aye. It were just like a doll you know. Wife were cut up about that. It must have upset sommat and she couldn’t have no more you see. I don’t know what happened like but, no.

Is your lad still living Billy?

R-No, he died at sixty four, he died about nine year since at Cleveleys, aye. I’d given ‘em, we’d given ‘em this boarding house and we come here, they lived here and we swapped. Aye well, they did seven or eight years in it aye, and then he had cancer o’t lung. I thought it were cigarette smoking, they were smoking day through you know, swallowing smoke. Aye, it were a big blow to me were that, me main stoop went [support]. Now when t’wife died I were here on me own for about eight years and then they left the boarding house and bought a house at Cleveleys he says Now when you get stalled of being be yourself, come and live with us. But you see he died. Now his wife, of course I kept going off and on, well, I’d be there about eight month once you know, but she started a being poorly and t’doctor said she hadn’t to have anybody, she couldn’t look after nobody so I’d to get back here and you know I’d selled him this house, him that I’m living wi’, thinking of being there you see. I’d left it and it were allus in me mind you know but that’s how it happened you see. Aye.

So you finished up outliving ‘em all Billy.

R-Well aye.

There’s your family left isn’t there, your sisters.

R-Aye, there’s six of us. Aye.

When you think, you know, you must have been good stock, your mother and father.

R-Well it looks so. Well me mother, me father, he weren’t a big robust chap but he used to get on the spree. When I started a doing for him you know he’d worked hard up to getting a family up but he used to get at t’spree you see. They did get at t’spree a lot on ‘em, t’pubs were open all day and they used to strike t’spree and then they’d happen go twelve month and have another one do you see. Well, he used to get on’t spree and I were doing for him you see, aye. Well, he didn’t do his self any good you know with that, no, no.

Would you say there was more drinking then Billy than there is now. When I say more drinking , more serious drinking you know, drunkenness?

R-I don’t think there were. There were no women went in pubs then, no. If you saw a woman going into a pub there’d be an outcry in Barlick. Eh no, no women went in pubs then, you know what I mean. There were no lads like there is today, that were then you see. In’t bulk you know. But there were odd ones, there were Tom o’th’Edge and one or two more I could name, Aaron Nutter, one o’ Jim Nutter’s brothers and there’d be about three or four of ‘em, aye. They’d go in a pub, they were in all day, fall asleep in there you know, aye. And then they’d be all reight for happen six or eight month, practically teetotal in a way and then they’d have another break out do you see. Aye. Now me uncle Will [father’s uncle] were t’same. He lived wi’ me grandmother next door to us in Newtown, he were t’manager at Brook’s. He used to go on t’spree and me grandmother ‘ud say Go and tell thee uncle Willy he has to come home. It were night you know and I used to go in t’Milker Tap. It were, you know where that telephone box is at t’side of Railway corner [now moved to Post Office block] well they used to go through a ginnel theer into t’tap room. It belonged to t’Railway pub but it were run wi’ old Lizzie Milker they called her, old Lizzie Cawdrey, Milker, she ran it, th’old woman you know, aye. I used to go there and I used to open t’door but you couldn’t see ‘em for smook. [laughter] I said, Me Grandmother says me uncle Willy has to come home! Aye, all reight, aye. Well, he were missing from his work you know and then when he come round sober I’d to go and ask Robinson Brooks if he could come back. [laughter] Aye. I says, Me uncle Will wants to know if he can come back. I were nobbut a lad you know. Aye, he says, Tell him to get back. Eeh, I’ve seen some dos I can tell ye, aye. There were old Aaron Nutter and Tom O’th Edge, they once come out o’t Railway one Saturday night and they were ‘I care for nobody’ and one on ‘em says ‘And naybody cares for me’, and they were staggering about you know and they were they were like that and all. So Tom says Thee and thy nobody, I wish tha’d be quiet. Aye, and they started feighting at finish, it’s a good job t’police weren’t there, they’d hev locked ‘em up!

[Laughter] Aaron Nutter ‘ud be old Jim Nutter’s brother would he? That were James that finished up at Bancroft?

R-Old Jim’s brother aye, that’s it. He were cut looking down at Bankfield when Nutter’s were there and Jim had gone down soon one morning, he used to go down afore he went to market [Manchester Exchange] He used to come down afore t’mill started you know, same as t’boss does to see like how…. Well, Aaron hadn’t landed you know and he’d to cut look. So he like waited and he landed about twenty past six and they’d started. Narthen, what time ‘s’ta call this? We start work here at six o’clock, think on that! Aye well Jim, I’ll tell thee what happened, I were coming on be Crow Nest and I stopped to leet me pipe and I had to turn round wi’ me back to t’wind. An I fon [found] meself back home again! Well, that did it. [laughter] He were a rum ‘un were Aaron aye. Aye he says, I fon meself back home and I’d never turned back! Well, Jim could do nowt, he turned round and buggered off then, aye, he left. Course, they were all reight, eh dear! [Laughter]

SCG/13 January 2001

5728 words

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 78/AB/4

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON 1ST AUGUST 1978 AT 17 CORNMILL TERRACE, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS BILLY BROOKS AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Last week you were telling me about moving boilers. You know, they were moving boilers through the main street by hand.

R-Yes, yes they were. On sleepers and round iron plates. You see, when they’d crowbarred the boiler so far they’d take the plates out of the back and [put them under the front] and that’s the way they went, aye. Round iron plates they had and sleepers, aye. Oh aye, I seen ‘em shift a lot of boilers. I remember before the second world war they fetched a boiler out of Butts into Calf Hall, one bigger, a bit bigger.

That’s it aye, Brown and Pickles did that.

R-Did they. Cause I know it were a bit, them in Calf Hall I think they weren’t as high a pressure so they put a bigger one in out of Butts. [1936 when Butts had finished weaving]

That’s right, they did Billy. Those in Butts were 180 pounds to the square inch. And what they’d done, Brown and Pickles had rebuilt that engine at Calf Hall, put heavier studs in and a thicker piston and they raised the boiler pressure to get more power, they were short of power so they put that bigger boiler in.

R-Well you see, they’d put an extension at the top [at Calf Hall Shed], that were a 1200 loom shop same as Long Ing but they built a 400 loom space at t’top you see for Bird, Charlie Bird and them ran it at one time. Well, that were how it were you know. They’d have to strengthen it up wi’ a bit bigger boiler.

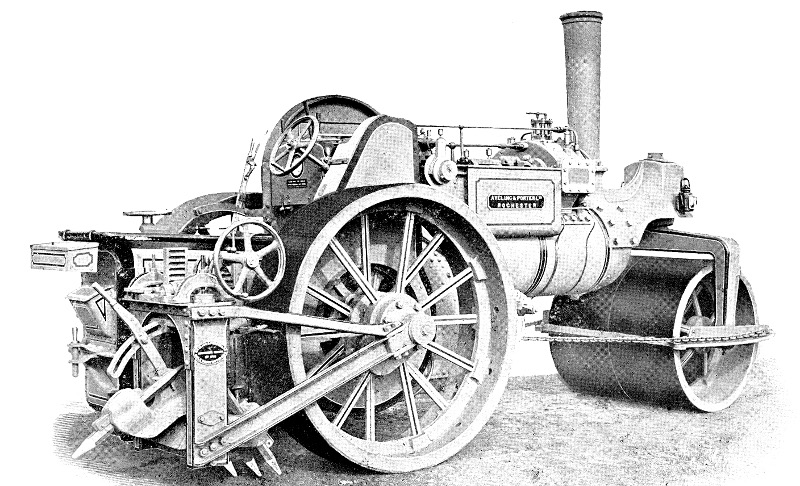

You were saying last week about the first road roller, steam roller.

A 1911 Aveling and Porter roller similar to the one that the council bought.

R-Oh aye. Steam roller, well it come at Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee did that. In 1897 it were Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, sixty year reign, th’old Queen. And when it come, it come from John Fowler’s at Leeds and it had on it Diamond Jubilee, aye. First time I saw it, it were up Park Road one dinnertime when I went home for me dinner. I were generally looking at it you know. Aye, but you know it were all limestone roading then, there were none o’ this black stuff. It [the roller] didn’t make much impression on ‘em when it went over ‘em because it were hard stuff you know but that’s what we had. I can tell of ‘em covering Church Street wi’ ‘em, you know, stones that size [indicates about pigeon egg size] you know that had been knapped at t’road side by men that used to take ‘em [contracts] by t’lump, so much a lump. They’d tip ‘em [the stones] at t’road side and they had a long [shaft on the hammer] made out of a tree [green, not seasoned]. And they had one a bit bigger [a hammer] and they used to break the big lumps into lesser pieces and then they finished ‘em off with a lighter hammer you see, aye. They had a bit of spring in did them there shafts wi’ being off trees. They covered Church Street from one end to t’other and when I look back I wonder how the devil they ever get trodden in. A lot on ‘em you know never get trodden in. Cart wheels used to make a rut you know as time went on and then they’d sweep the gutter, a bit of slutch, and throw it on and that’s all you used to get. Aye, road making today, it’s as easy as falling off a flitting, aye it is. Well you know they used to pitch ‘em you know, about that depth [indicates 12”] you know put stones in like that you know.

Old Barlickers still call this small overgrown yard on Manchester Road 'Poor Bones' because it was where stone was broken for the roads to qualify for Outdoor Relief from Skipton workhouse.

That’s it, on their ends.

R-For a pitch in the bottom afore they put the little ‘uns in. Eh goodness, they don’t seem to bother today, they throw that there little stuff on and still, they seem to hold all right don’t they. [What Billy is describing here is the classic water bound stone construction as used by the Romans and perfected by Telford and Macadam.]

Aye. Was there any causeway?

R-Aye, there were, it were flagged, all flagged. Some on ‘em is yet you know. Aye, they were all flagged then there were none o’ this [tarmac] Then they started getting that stuff from somewhere, where it’s always boiling abroad somewhere you know. It were baked in little round cakes [Trinidad Lake pitch and asphalt] and they used to boil it in a like, kind of boiler you know, in the road. Then they used to put them setts in and they ran this pitch round ‘em in the cracks you know wi’ a big tin wi’ a spout on. They filled up all the cracks you see. Well then, of course in Newtown they put them little square dos in but they were a bit slippery, aye they were very slippery were them. In frosty weather, or even wet weather, they were slippery so they were condemned were them. So they covered it over and as I were telling you last week, when Pendle did it up [Newtown] , they bared them all. Well, they were a good bottom them you see. I telled t’chap, I says I saw them put them down seventy years since, aye, aye.

A small tar boiler. The normal ones were larger than this.

Will it be a lot cleaner walking round the town now Billy than it were then? You know, say it were a reight mucky wet day.

R-Oh aye, it used to be mucky you know, it used to get a bit slimy, the roads then you know. Because it had getten like dust wi’ the traffic and one thing and another. Well you know, when it got wet it were kind of slutch. Women in them days used to wear long frocks and when they were walking they used to hold their frocks up like that or sometimes they had hat guards to hold their frocks up you see frae [the slutch].

Aye, what did you say Billy? Hat guards?

R-Well you know they used to sell hat guards at one time because everyone had a straw hat you see.

Oh that’s so that if your hat blew away it caught it like.

R-Aye there used to be a clip and then into their ear(?). And if it blew off you know it hung down. At Barlick holidays you know there were a chap, he were a tramp weaver called Big Matt, and when you got off the train at Central Station (Blackpool] at Barlick holidays he were there selling hat guards aye.

That were Central Station at Blackpool?

R-Aye, it’s been done away with now. At Barlick holidays train used to land at about half past eight and Big Matt were stood there you know shouting ‘Hat guards here!’. Aye, they all used to get one because we all had straw hats you know.

When they were building these mills, when they first put ‘em up, how many of the mills in Barlick had a whistle Billy?

R-Well, Calf Hall had one, we used to call ‘em donkeys. Has donkey gone? Aye. Butts had one, Wellhouse had one and Long Ing had one for a while. I remember one weekend, one Sunday afternoon, it were a reight calm day and me uncle Will lived with us in Mosley Street at [that] time, he were manager for Brooks at Long Ing. Now they’d blown the boilers off at Saturday you see. Now then, David Akrigg, he lived in the mill yard, there’s two houses there at t’side of Ouzledale works and he lived in one. Well, he used to light the fires at Sunday morning and that there whistle, it were at the back of the tape [Connection. The pipe up to the tapes was always a separate connection at the back of the boiler and the supply for the steam whistle was evidently connected in the same place.] The cock had a handle on and when it went cold the weight of the handle made it drop down and it was open, do you see what I mean? Now when David lit his fires and he started making steam he couldn’t get back in the mill you see and the whistle started right low down, Brrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr and they could here it all over Barlick. Well it sounded reight weird you know. Gradually frae a reight low note, as his steam get up. {laughter] Well, everyone were out, we thought there was sommat wrong. Aye, me uncle Will went rushing down to open the door and shut it off. I remember that, aye!

Had he blown down after the holidays started then?

R-No, they used to blow off many a time at Saturday morning when th’engine stopped they used to blow off you know and then light ‘em, might have been doing the flues out, I don’t know. [The main reason was to get scale out of the boilers because water treatment was very hit and miss then. Very wasteful practice.]

Aye, that’s it.

R-But you see he used to light his fires, he lived in the yard, he used to light his fires at Sunday morning you see, aye. They didn’t blow off every Saturday but I know when I were coming out it were blowing off you know.

Were that at Long Ing?

R-Aye, Long Ing.

When you say he lived in the yard, whereabouts did he live Billy?

R-Well, there’s two houses there, have you seen ‘em on the canal side? Well, he used to live in one and one of the tacklers at Brooks, Tom Smith, Old Tom Smith, he lived in t’other, he were a knock kneed chap aye. Well, David were the fireman there and he were a good fireman were David, he could laik wi’t job and it were hard fired were Long Ing at that time afore they got them, they put two bigger boilers in you see. But they were only 100pounds pressure you know and they added Brook’s shed on and they were hard fired. And a chap called Jack Trayford [was firebeater] you know and he were allus at full tilt and David, when he come, he used, he seemed to have it at his finger tips, he were a good un were David Aye. But he wanted th’engine job at t’finish, you know he’d knocked about a lot, upstairs he knew a lot and he’d have been all right but they brought a chap in called Oliver sommat, his daughter married Edward Holden. They didn’t let him [David Akrigg] have it so I think he left Barlick shortly after did David aye. But he were t’best fireman that there were, in my knowledge, as far as I know owt about it because he seemed, never seemed to be ruffled by the job you see. I’ve seen many a time when Robinson Brooks ’ud say to me father, Don’t come while breakfast time, it were in winter time, he says [Wait] while things get warmed up. A bit hard fired you see and he didn’t want the tapes pulling at it until everything had getten going. So many a time he knocked the tapes off while after breakfast at Monday morning in cold weather. But they got two fresh boilers in, they stopped a fortnight to do it, they did it in a fortnight. They get them old boilers out and it were, Hyde Junction it said on them when they’d taken them out, it were on ‘em you see. [Hyde Junction was the name of the part of the Great Central Railway Company where Daniel Adamson and Co. of Dukinfield had their private railway siding. The firm started at Newton Moor in 1851 but later moved to a 13 acre site near Hyde Junction [now called Hyde North Station] It was common practice for boilermakers to stencil their firm’s name on boilers before transport and this could survive for many years under the lagging. What Billy saw was almost certainly the remains of Dan Adamson’s address on the old boilers.] Hyde, aye, I remember that, aye, but they were nobbut 100 pound pound pressure weren’t them you know. Well, what they put in were about 150 pounds or sommat like that, you see they were more, aye. They’ll be in yet will them you know.

That’d be Hyde near Dukinfield wouldn’t it.

R-Aye. Now if you went down to Blackburn, through Blackburn Station you’d allus see a lot of boilers in’t yard on stilts you know. Whether they were there for, I don’t know, happen someone ‘ud buy ‘em you know, aye. I allus noticed that, there were a lot of boilers in Blackburn Station goods yard. Happen someone ‘ud buy ‘em at one time or another. And now they seem to be buying ‘em for tanks up and down.

Yes, that’s right.

R-There’s one down at Windle’s Garage there. Gissing and Lonsdale has a big ‘un in their yard. Aye, I’ve seen several.

Aye well, you can’t get a good riveted vessel now Billy, there’s nobody making ‘em, they’re all welded.

R-No, they brought some boilers up out o’t Wellhouse here when they went on oil and t’chap says they were as good as new when he were breaking ’em up. Aye, it looked a pity.

Same wi’ them at Bankfield, they’ve just taken them Bankfield boilers out you know.

Bankfield boilers going for scrap.

R-What, lately?

Yes, within the last couple of months. They’ve put a brand new boiler house in round the back, coal-fired. The old Yates boilers have been taken out. They were put in in 1905 when they built the shop and they were good boilers you know.

R-I can tell on ‘em christening the first pair of engines [at Bankfield]. Dicky Roundell that selled ‘em t’land from Marton Estate, he selled ‘em the land you know, t’Roundell family, to build t’shed on and he come to christen t’first pair.

And what did they call them?

R-I never knew, no.

Who built Bankfield Shed Billy?

R-Well, it were a company you know, they were all Barlickers in you know. Bill Bracewell, he were one shareholder and Nutters and Bradleys were in as well.

That’s it, the Barnoldswick Room and Power Company.

R-Aye, well, that were Calf Hall started Barnoldswick Room and Power Company. Calf Hall Shed Company started that when they bought Wellhouse and Butts and then they built Calf Hall Shed and called it the Calf Hall Shed Company do you see. [Billy has this wrong of course. CHSC were called that from their inception before they bought Wellhouse and Butts.]

And when they built Bankfield they called it Number 1 and Number 2 didn’t they. They just built one shed first didn’t they?

R-Well you see there’d be about 1800 looms, there were Nutter’s and Bradley’s, that’s all there were, two firms and they’d have about 900 looms apiece, sommat like that. Now then, they built an extension and John Sagar and his son Sidney had some and Horsfield and Wright’s and them you see. Well, they built that to it and a different type you know wi’ glass at t’top same as a shed you see.

Aye, that were 1910 when they built that. Do you know anything about John Sagar?

R-He had the quarries at Salterforth and he were a slave driver. His son Sidney ran the business and he died a few years back. He lived up Park Road and at latter end they were sawing stone at t’side of the road and there were a chap had some silicosis or sommat and he got so much damages and Sagar couldn’t pay it, I don’t know how he went on, he weren’t insured. He lived up the top of Park Road going up that way, aye.

You’ll be able to remember them quarries up there being very busy?

R-Aye they were at that time. They used to be sett makers then. There were George Smith, he were a grocer afterwards, George Smith, Peter Sugden, Harry Cawdrey and several more were sett makers. They used to go working year after year making them square setts. They had some rails frae out o’t delph reight down to the canal side you see and wagons and they used to lower them down wi’ ropes you know on a pulley and he once had a little tank engine did John Sagar to pull these wagons up and down. He hadn’t it long, it were a little tank engine you know like you might have called it a shunting engine. Aye, I remember going up one time to look at it. It tippled ower once, I think when it were coming round that bad bend in the field, it were a rough do. Reight down there to t’canal, there were a wharf built there you know, a stone wharf.

Opposite the pub?

R-No, this way. [There were two wharves, one at Park Bridge on the New Road which served Sagar's quarries on Salterforth Lane and one at the old boatyard on the other side of Salterforth that served Park Close Quarry on Salterforth Lane.]

And they had a little railway line running down there did they?

R-There were a line and it used to pull wagons there, I don’t know how they were pulled up, I never fairly knew that. [By horse in the early days.] Whether they were twined up like a crane I don’t know. But they used to let ‘em run down you know and they tippled ower once and all t’setts flew out you know, all t’damned lot aye. ‘Cause you know they come round t’bend you see and I fancy they got off too fast. [laughter]

Did John Sagar have all those quarries up there, both Salterforth and Tubber Hill as well?

R-Well no, I think there were one belonging to the Salterforth Company [Could be Salterforth Stone and Brick Company, Park Close Quarry. Mentioned in evidence to the Light Railway Commissioners in 1906 as being employers of 50 workers. This was the quarry on the west side of Salterforth Lane] It runs in my mind there were sommat o’t sort aye.

Yes, ‘cause there’s really three quarries isn’t there, one each side of Salterforth Drag and then Tubber Hill quarry at t’top of Barlick.

R-I don’t know where they’re emptying these here tanks of rubbish, I don’t know whether they’re taking ‘em there. [In the 70’s Gibson had bought the west quarry and was using it for infill as a private tip and scrapyard. The east quarry was a car-breakers and scrapyard as well.]

I don’t know where they’re taking them to. They did at one time, I think Pickles took them up there and tipped ‘em in the quarry but what they do with them now I don’t know.

R-Well, Barlick Council were using it as a tip at one time but they complained did Salterforth, said it’d breed rats and all that. And there’s some houses you know so of course they had to find Rainhall Rock then you know, aye. [Billy was a Councillor at one time so he’d know about this]

Can you ever remember them having a little stationary engine at the top of the quarry to pull the stone wagons up the hill Billy?

R-Aye, I can tell o’ that, aye. There were a bit of spare ground at the top weren’t there.

That’s it, a bit of an island.

R-Aye, I can tell of them having, aye I remember that.

How did they manage that job Billy, can you remember? Did you ever take notice?

R-Well, I’m a bit hazy about it but I remember it like yes. I remember it quite well.

It doesn’t matter Billy, don’t let it bother you. I’ve been told that there was a little engine there and that they used to have a rope down the middle of the road and they used to hook it on to the quarry wagons that were pulled wi’ horses to give them a hand up the hill. ‘Cause once they’d got up that hill there were only a little bit of a pull and then it were downhill all the way into Barlick. The Feller that told me said it was comical, sometimes the rope ‘ud wear a bit and they’d have to cut the weak piece out which would shorten it a bit, you know, take the weak piece out. And he said that it meant the horses had to come a bit further out of the gate with the cart, but they knew just where to stop.

R-Well, they kept altering all their gadgets you know as time, as years went on you know. They’d try sommat else, well, I just forget now. We used to go up there and watch them as lads you know.

Well, about that time just about all the stone would come out of there wouldn’t it?

R-Oh aye, and they used to send them setts to Leeds you know and all t’way on. On t’canal you know. They were all paving ‘em then, it were just coming out. They were paving all their streets and you know when horse and trap went ower them it didn’t half rattle. If you went to them big places you’d hear that rattle. Now you know, they’ve had their day and of course they’ve been superseded wi’ tarmac do you see.

And those fellers that were cutting setts up there, would they be on piece work?

R-Aye, they used to take a lump. They’d hoist a big lump of stone wi’ a crane and you’d get so much for doing that. Aye, piece work you know, aye. Then they used to put big wedges in you know and bloody clump ‘em, knock ‘em into sizeable pieces. [Large blocks of tone were cracked by using ‘plugs and feathers’. The technique was to drill a line of holes across the block on the fault plane. Two ‘feathers’ are placed in each hole; these are like curved liners, if you take a piece of pipe and saw it lengthways you have two ideal feathers. The feathers reduce the friction of the ‘plug’ on the stone. The ‘plug’ is simply a solid steel spike which tapers to a point. The plugs are inserted inside the feathers and then driven home progressively along the line of holes. This builds up a line of stress on the stone and even a large block weighing perhaps fifty tons can be split with relative ease. The same technique was used for splitting blocks out of the quarry face.] Then they had a kind of a bench, you know a big [bench], and they used to make these setts, they called ‘em sett-makers. Now when we used to have very long frosty winters, three months at once in the 90’s and they were out of work you know, all th’out door chaps were out of work. Aye, some of them had families and they had nowt you know. They used to have to strap at t’shops you know. [strap = buy on credit] Well, they started a working again, well, they got their families up you know, they used to owe money while their families started in the mill you know and then they’d buy their own house. Used to buy their own house, they were only about 4% or 3 ½% interest in them days you know. Houses like this [two up two down terrace] were nobbut about £130 you know . You could buy a big house across the road [three bedroom high class terrace] for £370. A good big family house wi’ garrets in, £240, a new un. Well they bought their own houses did the old families that had struggled up you see.

Would they buy them through the building society Billy?

R-Yes, yes, aye folk did.

You know nowadays sometimes people have difficulty in getting loans off building societies if their wage is below a certain level. Would you say there was ever any bother then getting a loan off a building society?

R- I can’t remember any trouble but there might have been you know. Of course I didn’t bother about that sort of thing in them days you know but I remember a tremendous lot of families come into Barlick after the Barlick Strike and settled down here out of Lancashire and got their children going into weaving. It were so simple you know, just two up and two down you see, plain weaving and they got on. [Billy isn’t talking about houses when he says two up and two down. He’s referring to the number of healds in the loom, four, which meant it was a simple plain weave and therefore a job that children could quickly learn. This meant that it was so easy to get the children earning in the mill.]

When you talk about the ‘Barlick Strike’ you mean when they were out on and off for nearly two years?

R-Well, it were over a simple thing, it were owing to preferential tariff you see. Barlick Manufacturers, they’d pay about 2% less for disadvantage wi’ not being on a main line. Local Disadvantage. Now then, they [the workers] wanted paying up and it nought [only] meant about a shilling a week difference.

What year would that be Billy?

R-I were thirteen years old, I were just full time so you can reckon its 82 years since.

1895 then.

R-It fizzled out at the finish, they all got full up wi’ folk coming out of Lancashire so they had to go back for the same as they had started.

Can you remember the older end talking about the Cotton Famine Billy, in 1860?

R-Well I’ve heard, aye, I used to hear me Uncle Will and them talk about it aye. But I didn’t take much interest in it you know them days. No, aye I used to hear ‘em aye. There were a strike in 1909, I know I were taping at Coates at the time and I hadn’t been wed so long and I were a bit hard up in them days and there were no wage, no nowt, aye. So one o’t bosses let on me as I were knocking about and he says How are you like? I said Well, I’m not so good. Well he says, Come up to the mill and you can have £2. Well it were a lot of brass then were £2, I could live for a fortnight off that. So I got £2 and paid ‘em a shilling or two a week [the shopkeepers he was in debt to] every week off it, aye. I remember that, I hadn’t been wed long and I’d naught been weaving. Eh, I don’t know, there’s been all sorts, aye.

Were you in the union then Billy?

R-Yes, there were a Barlick branch but they were amalgamated to Lancashire Textile, Northern Counties they called it. They were amalgamated really but it were a separate union were Barlick. Now they ran out of brass you know and of course Northern Counties had to [bail them out], aye.

Which union were that, you’d be in the weaver’s union then wouldn’t you?

R-Weavers, winders and Beamers.

Did tapers come under the beamers?

R-Oh I don’t know about the tapers. I don’t think they were in, no, they weren’t in’t union while sommat like 1948 or sommat of that. It were after we’d gone to Blackpool. And a chap come round to try to get ‘em all in and he got ‘em in and then they had to pay tapers for meal hours whereas they didn’t get paid for meal hours before.

Aye, that’s it because a taper keeps running doesn’t he, he doesn’t stop. [Taping is a continuous process and didn’t stop at meal times. Tapers always made sure they weren’t caught at stopping time with a warp still running. The only time you could stop a tape without waste was at the end of a warp.]

R-All day through and he didn’t get, you know he had very little more than a weaver in a way. He wouldn’t have a pound a week more and he’d to work them hours. But after I left, well, he come a seeking me did t’chap once. He says I’m getting ‘em all in a union. He were frae Nelson. Bit I were barn to leave so I says I’ll not bother ‘cause I went to Blackpool.

So up to then, after WWII none of the slashers ‘ud be in a union then at all?

R- No they wasn’t, no just shortly after that they got in. Now me brother got on well with his wage, it got up to £14 a week through that. Now when I left in 1943 I were getting about £6. He finished up wi’ £14 a week because they’d getten so much put on for them hours, an hour and a half in the day you see.

When you were taping Billy, you’ll be able to remember the days when they were sizing for weight won’t you, when they were putting clay in?

R-Well, yes, there were all sorts of does like china clay, aye.

Can you tell me Billy, why did they put china clay in the size?

R-Well, it were to weigh you see. It were to put a bit of weight on. They knock sommat off for that you see, happen two counts less or sommat o’t sort.

Yes, that’s it. So like if you were weaving , if you had a cloth construction that were say 30s in the twist you could get away with 32s if there were plenty of clay in it.

R-Well they’d happen, they’d knock happen a count off or happen sommat off in’t weft do you see if they could manage to do that. But when I left things had altered drastically, they never used any clay nor wheaten flour neither, just starch. That’s all because they could sell it, it were booming after the Second War there were a boom, they could sell it no matter what it were and a good margin off every piece. Whereas before they were splitting halfpennies in two and all that carry on, aye. I’ve seen us put a two hundredweight bag of clay in a mixing you know. They’d be like flour millers were the weavers when they came out. It used to fly off a lot on it, aye.

It used to cause a lot of bad chests and all didn’t it?

R-Well you see, it dried the yarn up you know.

Did you ever have any bother during the war with, I’ve heard Joe Nutter and Norman Grey, the tapers at Bancroft talk about during the war, using pure tallow and it were a favourite for chip pans during the war. [It was a good source of fat which was rationed.]

R-Ah, well, I don’t know about that, it used to be tallow and smelt a bit, well, some of it did. I once got rocked [rooked, cheated] when I were at Blackpool in t’boarding house. A chap come with a drum of ‘Good cooking fat is this if you want a drum’. Well, I were fast you know. I get it bought off him and when I’d getten a good layer of fat off it were tallow underneath. It stunk th’house out. Aye, bloody hell! It stunk th’house out.

Aye, ‘cause there’s different sorts of tallow isn’t there.

R-Aye, well, we used to get some tallow at Coates and it didn’t smell as bad. It were like softish as though it had some oil among it. I don’t think that ‘ud smell.

Aye, we get some tallow now and it’s pure tallow. It’s as white as snow and do you know it’s beautiful, it doesn’t smell at all, it’s beautiful stuff.

R- No, well, we used to get some of that at times.

But it’s the most expensive. Course, all t’stuff to do with taping’s expensive.

R-Well, I used to get some soft soap some time. I telled him to get me some soft soap and I used to drop a lump of that in you know, soft soap, aye. A chap once told me, I were up at Rakery(?) and he come frae Nelson, he were a taper, aye. He were on about sizing for weight and he says I’ll tell thee what to do, don’t broadcast it and don’t tell nobody, get some size [decorator’s size] and put that in, it’ll mek it stick to’t yarn! Aye he did. But you know if you put too much of that in it ‘ud glaze that cloth and it wouldn’t tek t’dye t’same.

Aye, like wallpaper paste.

R-You’d to be careful about that, aye. Oh aye, they used to come up to t’tapers you know and say, Put a bit of weight in these, they’re a bit light. Aye, I’ll tell thee what they used to do. Them reedmakers at Wellhouse, they’d send their reeds [the manufacturers would send the reeds to the reedmaker who was in Wellhouse yard] and they’d make them into bastard reeds you see. They’d put about that width [indicates 3”] each side coarser reed you see. Well, that used to be a saving did that. You see there were a bit off trickery in that you see, they were what they called bastard reeds. If they were a 58 reed you know they’d tek them wires out and put wires in at a bit bigger gauge you see.

At each side.

R-Aye, and you couldn’t tell be looking at it. But they called ‘em bastard reeds, that were a dodge you see.

So actually the reed count ‘ud be different at each side than it was in the middle.

R-Aye but it weren’t noticeable unless you put magnifying glass onto it you know. And it meant you could put a few ends less in you see, you know what I mean, and still get the same width because there were a coarser reed at each side. Well, you got your 38” with less twist. Now it didn’t mean much per piece but when you’ve thousands of pieces it’s a lot.

Aye, it starts adding up.

R-Now they used to send reeds to them reedmakers, Johnson’s, they come from Clitheroe. They had a [place] down here. [In Wellhouse Yard] They used to send ‘em, to look like that. They’d put new paper on’t baulks tha knows and a bit of oil . You’d think they were new reeds, they were bastard reeds aye. Eh, there were all sorts of dodges.

Aye, they’d be up to all the tricks Billy.

R-Well you know there were keen competition in the cotton trade. In fact there were some times when things weren’t so good and they happen weren’t buying, trade had gone slack you know, you were happen working at a loss for a while. You weren’t getting enough per piece, what it cost you to make it and there’d be a boom come on and you could get what you liked nearly you know. You’d happen put a weaving on [a weaving order] what it ‘ud cost after you’d worked it all out and t’weaving were going to get three and odd for that, you’d put three and odd on, what they called a weaving when things were good and they were clamouring for it. But you see that’d happen last a couple of years and then it slacked again. That’s the way, cotton trade were allus like that, up and down. Short time a bit happen, all sorts. It got to it peak you know when all these mills in Barlick were, got to it peak about 1907 to 1920 it get to its peak, aye.

[Use of bastard reeds wasn't always sharp practice. They were often used to compensate for cloth contraction at each edge of the warp.]

SCG/Friday, 26 January 2001

5946 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 78/AB/5

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON 1ST OF AUGUST 1978 AT 17 CORNMILL TERRACE, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS BILLY BROOKS AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

[As the interview starts, Billy and I were discussing the economics of part warps and urgent orders. In order to get cloth out for an order quickly much smaller weaver’s beams have to be prepared with say two or three cuts on each beam instead of say ten. This means that more weavers are working on the cloth and it will come off the looms quicker but there is a penalty in that more beams have to be prepared for the weavers. This raises the cost per piece and this is what Billy and I are discussing as the tape starts.]

R-They wanted ‘em out in a fortnight, aye. He’d taken that order to deliver in a fortnight.

That’s it, so you were taping part warps.

R-Aye, just two cuts on each warp, on each beam.

Aye, yes. So that means more work for everyone all round ‘cause it takes just as long to gait a short warp.

R-Well they had to pay more for twisting you know, it were all hand twisting then. But t’price would be on for all that you know. If you wanted ‘em reight sharp you had to pay for ‘em you see. Now you might have a customer that wanted ‘em reight sharp and so you know you’d say well, I know where I can get ‘em in a fortnight but I want so much, clapped it on. Well, it paid, everybody that wanted that cloth, they’d all have to pay more for it you see, ‘cause they wanted it there and then. That’s why they used to take them little orders sometimes, they all did it because they were getting a good price for them.

Was there much cloth woven for stock Billy? You know, cloth woven when they hadn’t an order for it?

R-Oh aye, Brooks made thousands, sometimes they lost a lot of brass wi’ ‘em.. Sometimes they’d mek sommat. But they lost a lot of brass. He’d come in on a morning sometimes and he’d say I haven’t booked a yard, not a yard and 900 looms running. Put a set of so and so in. I’d know what sort he meant and I’d go and put so and so of us own make and so and so of bought beam to get me number, aye. [Billy is making a distinction between taper’s beams they had bought in and beams that had been wound from yarn package in their own beaming department. By using some of their own beams they could get the number of ends in the set right.] Well he’d come t’morning after and perhaps for a fortnight and say carry on. Piled up in’t warehouse with what they called ‘three reds’ and t’price dropped and they lost thousands on them did Brooks. Aye they did. They called ‘em ‘bread and butter sorts’ in Manchester, the three reds. [Three reds was the cloth mark for this particular cloth.]

Aye, Bradley’s got into trouble wi’ that didn’t they?

R-Did they? Aye.

Yes, they were in Bankfield No. 1 with Nutters and I think they banked in the end with the job.

R-Well happen they must have done because they give ower didn’t they and his wife were tekking in lodgers down Gisburn Road. His widow.

Well that’s what I were told, their warehouse was absolutely full of cloth.

R-Well, when he started he were a baker on Commercial Street They were bakers, they had a baker’s shop there he’d never no experience in that sort of thing. [manufacturing]

Where did Bradley start weaving?

R-They started in Butts at far end there, in Monkroyd end.

That’s it. How many loom would he have.

R-About four hundred. And during the strike [1895] they gashed ‘em all one weekend.

Aye, warp slashing. Was there a lot of that went on Billy?

R-Nay I don’t think there were, I don’t remember, only that. Course, they might have been insured you know.

[Pause here while Billy and SG light pipes]

R-It seems good bacca, what sort is it, Condor?

Aye, oh that weren’t Condor you had last week, it was Escudo.

R-Oh, I thowt it were very good.

Aye it is, it should be, the price of it Billy. D’you know what an old feller told me one day Billy? He said Trouble with smoking a pipe nowadays is if you smoke your own it’s too expensive and if you’re smoking somebody else’s your pipe won’t draw. If you’re smoking some bugger else’s your pipe won’t draw. [Much laughter from both! For non-pipe smokers, the point of the story is that if the tobacco is free you cram as much as you can into your pipe and it won’t draw properly!] Eh, never mind. No, that’s one of the things that’s always amazed me about this job, the way somebody could start as a cloth manufacturer with almost no capital and you’d think, almost no experience. Because there were several people that did it weren’t there. Coal merchants, bakers, all sorts of people went into manufacturing. [You might smile about us lighting our pipes but as I think you may have noticed, Billy and I got on well, we were both pipe-smokers, and a fill of baccy lubricated the interview!]

R-Aye, you know at time that these mills were going [about 1900] you could buy a Coopers 38” loom for £5. Aye. What would they be today?

Oh, God knows.

R-Hundred?

Oh, a lot more Billy, a lot more. I mean, you couldn’t buy them, but you’d be into six, seven, eight hundred pound street now. I mean, they think nothing of paying fourteen thousand pound for a loom now you know Billy. Mind you, those are big automatics, but how long do you think it ‘ud take ‘em to pay for a loom in those days, you understand what I mean, before they’d paid for the loom?

R-Well, it’d take a few years you know to write ‘em off. They all used to come by boat. I can tell on ‘em, I can tell o’ t’Moss Shed, it were a field there, trees at each side and on t’back. At t’canal side they cut a way across, you know, made a bit of an opening in the bank, in the hill side and that were the start of Moss. A boat used to come wi’ bricks and all sorts and I watched it develop, I think it were a firm called Preston’s that did t’Moss, 1903.

Who built Moss?

R-Well, it were Barlickers, a company you know. Moss Shed Company. Same wi’ Barnsey, they were all Barlickers, main on ‘em. There were these engineering companies you know that [invested] purpose to get orders for cast iron and what not you know, same as Rushworths at Colne. They were shareholders at Long Ing, they got all the troughs, pillars and that.

Aye. Widdups ‘ud have a lot to do with Moss wouldn’t they.

R-Aye they had, he were a shareholder were’t father.

Aye. And then Barnsey would be built after that wouldn’t it?

R-Aye but you know you, a couple of hundred and you were all reight there. Them days, you get to be a director wi’ a couple of hundred, aye.

Is that reight?

R-Aye, a lot of brass were two hundred then. Nobbut cost £26,000 to build Westfield Shed, engines and the lot in 1911. That’s what brass could do then. You can’t realise it but it were so. Hundred pound went a long way in those days. You know they nobbut geet about fourpence an hour did labourers you know, fourpence or fivepence. They’d borrow off the bank , you see the bank ‘ud see ‘em reight you know because they had the assets going up. And they’d do business with the bank you see, bank helped them so’s they’d get some business when they’d getten going.

And for the same reason, a lot of people that built the sheds would help other people to get into manufacturing so’s they’d be drawing rent wouldn’t they. Because I know like that Calf Hall [Shed Company] ‘ud lend people money on their looms, to buy their looms.

R-Now all them power spaces were taken up, it were taken up by tacklers that had been tackling down there. There were Pummers, well they were all working in textiles you know. Pummers started, Windles started, there were Bill Bailey’s, they got to be a big firm, he were a tackler, aye. They were tacklers staring on their own you know a lot of them, aye. Old Jim Nutter that started Nutter and Company he used to be hawking bibles.

Who was Jim O’Kits?

R-Jim Edmondson, they used to have 400 looms in Crow Nest. They made their brass wi’ selling bibles did James Nutter and Jim O’Kits and all. They were them big family bibles you know. And they used to put the names of all their children in’t first page you know. We lost ours, me sister were on asking about it t’other week, as I don’t know where it get to. They cost a pound apiece.

In them days?

R-Aye they were, aye.

Like a pound ‘ud be a lot of money then weren’t it Billy.

R-Well, they cost a pound apiece.

And that’s how old Jim started?

R-He used to be selling Bibles, yes.

And where did he come from, do you have any idea Billy?

R-Well, I think he were born in Barlick, I think so. He used to be a big New Shipper [Methodist Chapel], and he were t’chairman one night , Well, he says, I can see a lot of smiling faces. You know things have been good for a while, we’ve had full work. In fact there’s more pianos bought today than there were tin whistles when I were a lad! They were all buying pianos then and now they’ve done away with ‘em. They cost about twenty pound apiece.

Well, that ‘ud be about the same as a colour television now wouldn’t it Billy?

R-Well, they’d all getten their children in the mill. Aye, and they were paying half a crown a week for ‘em [12 ½ p.] He [Jim Edmondson] says There’s more pianos sold today than there were tin whistles when I were a lad! He were a droll ‘un were [Jim].

Would he preach a bit down at t’New Ship?

R-Well, I don’t know whether he were ever a lay preacher, he might have done. I expect he would do but I forget you know.

Jim ‘ud start at Calf Hall would he?

R- I think they started in’t, I don’t know whether they didn’t start in’t Clough or not. I know Pickles started in’t Clough and Brooks started in’t Clough, now whether Holdens did I don’t know. I just forget but they did go into Calf Hall, they went into Calf Hall for a start.

Clough wouldn’t hold many would it?

R-Well, they were right in t’top. [Billy is talking about Brooks here], Aye, there were a good hoist and I remember going wi’ me father’s breakfast and I yelled damn murder afore I’d go in this hoist. They had to take me in, I were flayed of going up there.

And your dad was weaving at Clough?

R-Me dad were weaving a four loom up in the top. I remember going up and seeing them.

That’s unusual isn’t it, weaving up stairs?

R-Well aye but in them days if owt happened they didn’t bother. In th’Old Coates it were upstairs weaving, that mill that were pulled down, it were four storeys.

Did they weave upstairs at Long Ing and all at one time?

R-Not at Long Ing, no. They had two storeys, tapes and winders on the second storey.

Same as Bancroft.

R-That’s reight.

Aye, warehouse downstairs, tapes and winders and warp preparation upstairs, that’s it.

R-Joe Slater, one of Slaters, he married Billycock’s daughter that lived at Newfield Edge. And in them days there were no motors so Joe used to walk it from the station up to Newfield Edge you know. Same as Holden would, they lived aside of, nearly opposite your mill, that end house.

Aye, it’s a boarding house now. Springbank do they call it?

R-Well Holdens lived there, the founders of Holdens, they lived there. Aye, well, Joe [was walking past one day] where Donnie Smith lived at the end of Calf Hall Road there, just at t’corner, there’s little walls round, just at th’end you know. [The three storey cottages fronting on to Wapping on the Barlick corner of Calf Hall Road.] Them old cottages just at t’corner of Calf Hall Road as you’re going round [towards Barlick] Aye, and Donnie, Old Donnie Smith, he were an outdoor chap were Donnie and his wife were one of them old Barlickers you know. She were leaning over the wall same as they used to do in those days, you know gossiping and Joe were coming up. He says I’ve seen your Donnie wi’ a woman down yonder, he’s talking to a woman. She said Well, if he suits her as well as he’s suited me she’ll be all reight. [laughter] Dear me, there were all sorts in those days. Aye there were. Them characters is all gone but they were rum uns, aye they were. She used to come out wi’ all sorts did Smith’s wife, I knew her well, I knew the family aye.

The cottages Billy mentions in Wapping. Notice the road is limestone.

When you say Donnie were an outdoor man, what do you mean Billy?

R-He worked, he was a road man, you know, owt for’t council, Local Board as it was at that time. It weren’t called a council it were called a Local Board. Aye, a good old trooper were Donnie.

Tell me Billy, how about politics in them days, you know, was politics a big thing you know.

R-There were no Labour then. There were Liberal and Conservatives.

Were it a big thing Billy, you know, was there a lot of canvassing went on at election time?

R-Oh aye. They were very bitter against one another were Liberals and Conservatives in them days, oh aye. Aye, it were a do you know. There had to be a bit of sommat to create a bit of life in them days you see. There weren’t television or all this brass to set off wi’ in cars you see, there were nowt. Well you had to have sommat to be interested in you see, to raise hell wi’ sommat, aye. Now at one time when I were quite a lad they called Barlick holidays Rushbearing. I enquired off me uncle [Billy is actually talking about his great uncle Willie] and he says It weren’t a holiday really it were more of a festival and they had wagons decorated wi’ rushes you see, go round the streets you know and happen a band playing or sommat of that, aye. Well it used to be known for many a year as Rushbearing. And then they started calling it Barlick Feast and now of course it seems to be holidays. They don’t seem to use them expressions they’ve gone, they’ve been out lived. [It strikes me in 2013 that people might be wondering what the rushes were for. It's a hangover from the days when the local church had rushes and sweet herbs scattered for a floor covering. These were renewed once a year and used as an excuse for a bit of a jolly.]

That’s interesting is that Billy.

R-Now th’hearse that used to bury folk in them days, it were a black un all carved and on top of it you could see that there had been something on top and at that time it had big plumes on top but they’d done away wi’ ‘em ‘cause they wanted so much cleaning. It were kept in the railway yard, they’ve pulled it down now, it were kept in there and it were like a box wi’ black panels and carvings and they opened the door at the end and shoved the coffin in and when they shut it you couldn’t see the coffin, aye.

In those days, when you were a young lad was there someone who was an undertaker? A funeral director?

R-Aye, there was Dick Holroyd on Commercial Street, he were an undertaker. In those days the undertaker used to walk at t’front o’t hearse while they got down there, to t’Gill. You know, reight stately and bearers either side. They’d stop here [Junction of Wellhouse Road and Skipton Road] and t’bearers ‘ud get in and they’d go a bit faster down there you see. [To Gill Church]

Aye, that’s it, once they got out of the houses. And of course, people ‘ud be laid out at home.

R-They were all kept at home and t’blinds were drawn. T’carriages and th’hearse ‘ud draw up and drivers ‘ud get out and a woman ‘ud come out wi’ a tray and a white tablecloth over the tray wi’ some glasses of wine and they all had a glass of this wine, aye. All t’drivers, they’d come and this woman come wi’ a white apron out o’ th’house and they’d all get a glass, aye. Then t’coffin ‘ud come out then, aye. We used, as lads we used to watch all them things you know, we were allus interested, aye. Course, that’s gone now but it were nice to see. It were a nice little ceremony that were, aye it were, aye.

How about weddings Billy, were weddings any different then?