TAPE 78/AB/1

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 19TH OF JULY 1978 AT 17 CORNMILL TERRACE, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS BILLY BROOKS AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Billy Brooks in 1978.

[As near as I have ever been able to make out, Billy was 96 when I recorded the interviews with him. He was very deaf and I have tried to edit the worst effects of this out of the transcript. Though infirm his memory is amazing and every time an opportunity has been available to check a fact given by him has arisen he has been 100% correct.]

Mr Brooks is a very advanced age and I’m not sure how we’re going to get him used to the recorder, we’ll just have to see how we get on.

R-India.

Aye, for the Indian trade.

R-Aye, for India, there were a very big firm at Clitheroe used to make them, Garnetts or sommat at Low Moor and them were dhotis. [A loincloth worn by male Hindus.] Aye they were an old firm you know, they used to be [weaving] in the 1880’s and 90’s. when they were in’t go, aye. Same as Clough you know, well in’t Clough, in t’top hoil, Robinson Brooks started with eighty looms, Pickles started wi’ some looms, I think Holdens did, aye. Well Brooks flit them eighty loom, they were Pilling looms made at Primet Bridge at Colne, they flit ‘em to Long Ing in 1890 you see and filled up to 400. 420 I think they had there had Brooks, aye. There were some breakdowns there after they put ‘em in you see. [At Long Ing Shed] There were three [gear] wheels all into one another. There were a wheel that were on the flywheel and then there were a second motion wheel and then there were another on Brook’s line shaft through the wall and they hadn’t been going long when one flew in bits and flew through t’top. Burst an hoil in the top, I used to find looms wi’ bits of metal on, aye, I remember seeing ‘em. I were nobut , well that’d be about 1894 or sommat like that, I were about ten years old. [Billy actually said 1884 but as I say, there is doubt about his date of birth, even he wasn’t sure. As near as I can make out he was born in 1882 so I guess he meant 1894 when he would be twelve] Aye I remember seeing all that. Well, there were allus sommat wrong you know. That much vibration and then we were stopped three weeks wi’ the main shaft cracked, aye, we were off three weeks.

Did you get paid while you were off?

R-No, there were no pay, nowt then you know. Well, and then that wheel that were on the flywheel cracked and when it come it were too big and they couldn’t get it up to the wheel and they’d to bar it, they hadn’t a barring engine same as they have now. They had to bar it round, they had four men all night barring it round to shive [Shive means cut. Billy is talking about a gear wheel that wasn't running true to pitch and the cast iron teeth had to be chipped to make it run properly.] that bit off you see. It had too much shoulder at side and they had to hire men and they’d a crowbar you know and it were HUP! And that were all night through. Aye, there were some breakdowns, aye.

The jack gear and second motion that had to be chipped to fit.

What sort of an engine were that in there then Billy?

R-Yates and Thom put it in you know. [W&J Yates of Blackburn, 1887, before they became Yates and Thom. It was a double tandem with slide valves and the sides were named 'Lizzie' and 'Minnie']

The Yates engine.

What did they name the cylinders?

Oh, I don’t know. They were all them wood lags and brass round you know. They were nice, I know that, aye. They’d be t’same like as yours in a way they were the same. They were like two cylinders at each side to see to. But you know they hadn’t them valves that you have that clicks. [Corliss]

Aye, Corliss.

R-Well, you have them, they click back don’t they, these had to go like that you see. [demonstrates sliding motion]

Aye, slide valves.

R-Well, after a time they drove Brooks wi’ ropes. [See Newton Pickles on this. Billy is dead accurate] Now let me see, how did they do, I know, they let some big rope wheels into the wall, there were two big wheels for these ropes you see and they drove ‘em wi’ ropes and then in the end they put a little engine in in the same room as t’other one at far end, from a firm in Bolton. [Hick Hargreaves] Then the ropes went reight away on the engine house side reight on to Brooks lineshaft, it were a fair long way you know but it took the weight off the old engine then. Now they had 1200 loom on [originally]. Three firms had brought 1200 looms [and the engine was sized for that] but [with brooks 400] they had 1600 looms on.

Who owned Long Ing then Billy?

Long Ing Shed Company. [First room and power company in Barlick] Rushworths frae Colne were shareholders, and some of the old Barlickers. Robinson Brooks brother, William Brooks, he lived in Station Road where that building society has its office opposite the Liberal Club. [Croft House opposite what is now the community Centre] Old Willie Broughton and all. A lot of them that founded the Calf Hall Shed Company.

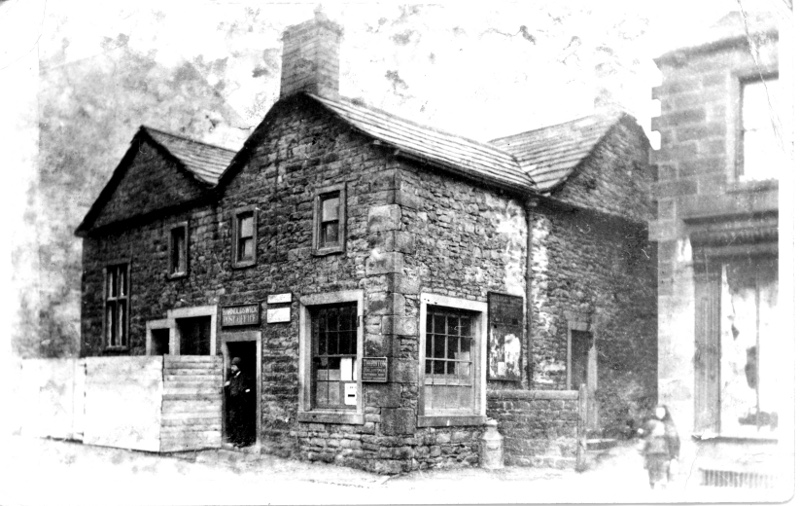

Croft House on Station Road.

Station Road shortly after 1892. Croft House is on the right with the sign on the gable end. It would be a private house at this point.

You started work at Long Ing didn’t you Billy?

R-I started work at Long Ing, half time, when I were ten years old. I’d half a crown a week [twelve and a half pence] and a penny for meself.

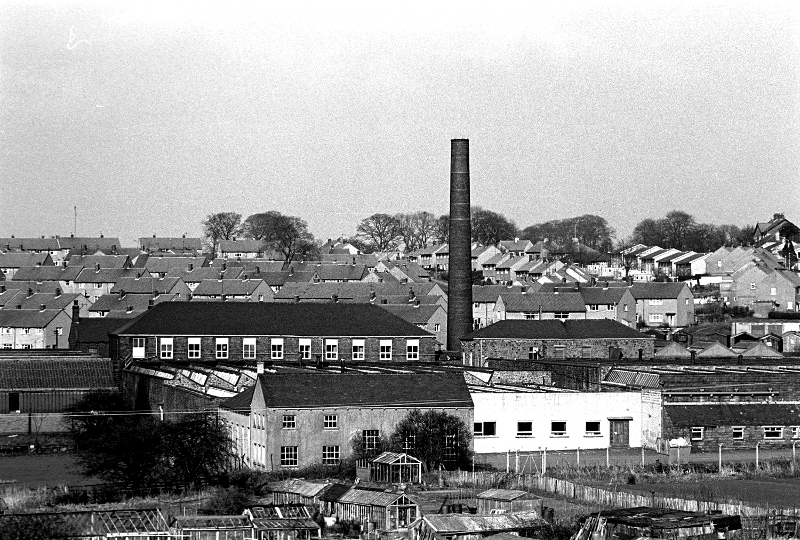

Long Ing Shed in 1985.

Who paid you the half crown Billy?

R-Well, I tented for a chap wi’ six loom. I were what I call a tenter and he paid me half a crown and a penny for meself. Aye, I went at morning one week and school in th’afternoon and vice versa the week after you see.

What year did you start there Billy?

R-[Billy gets a bit mixed up here but settles on the following] I were ten and I was born in 1882 so it was 1892. Aye, I went in wi’ me aunty to learn to weave at nine at Saturday morning at Long Ing. Aye, I went in at Saturday mornings after breakfast. They worked seven while twelve then at Saturday morning. I went in wi’ me aunty to learn to weave. Well, when I were ten I were ready for tenting you see, me uncle were the manager and I started tenting reight on me birthday you see.

Which firm were you working for Billy?

R-Robinson Brooks. Built Westfield. In 1911, Brooks and Slaters were directors of that mill. It cost £24,000 to build it. What would it cost today?

God knows Billy.

R-I’ll tell you how I know because one of Robinson’s lads used to come up to me desk in the tape room to do some writing and he told me.

So you got to taping at Westfield?

Westfield in 2005.

R-I taped there then, I taped there for thirty two year. I went there in 1911 or 1912 when it started. It says 1911 over the cart race for Westfield but then it might have been 1912. I were there 32 year, well until 1943.

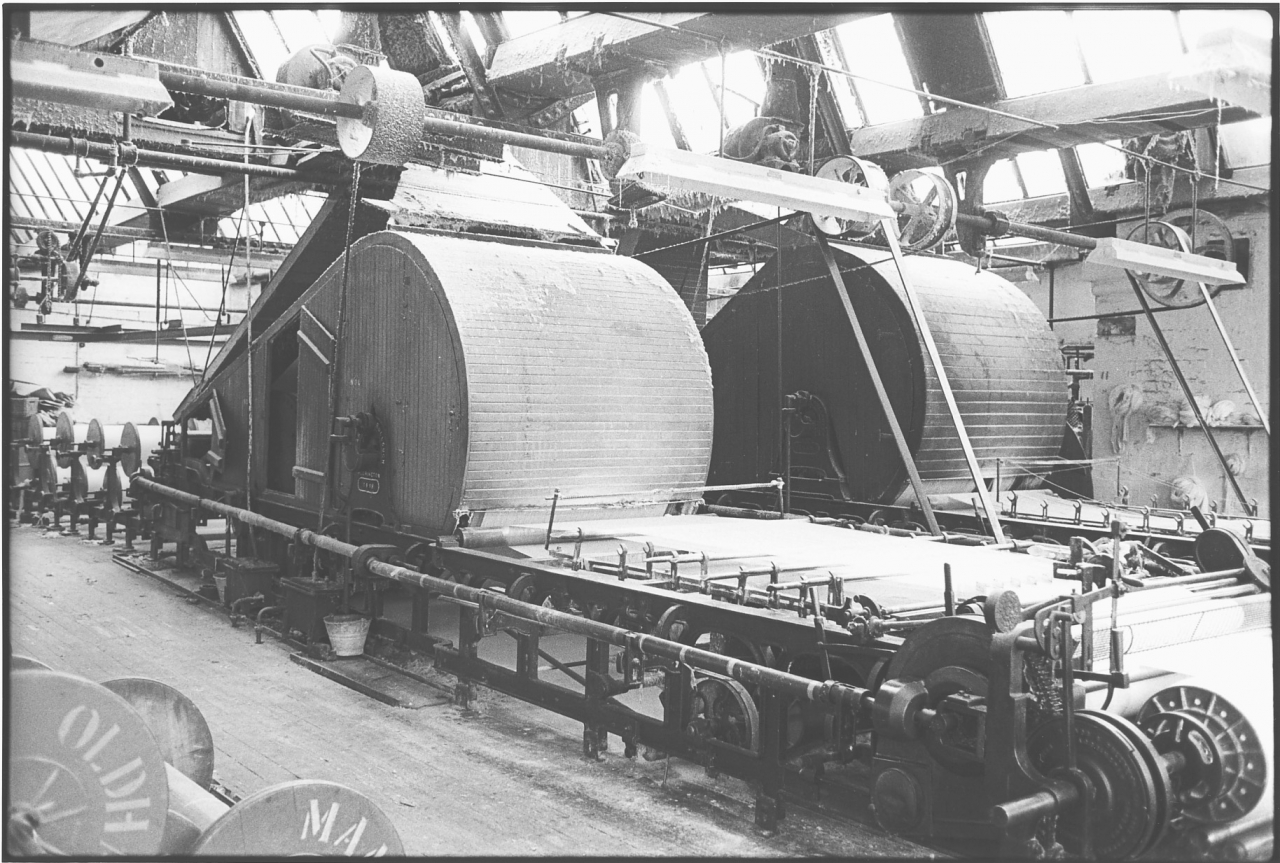

Tape machines at Bancroft, exactly the same as the ones Billy worked on.

Where were you born Billy?

R-Up in Newtown where Elmer’s chemist shop is now. It were two cottages then you see and they’ve made it into one shop now. They belonged to me uncle did them two cottages and he and me grandmother lived in one and me parents and us lived in 22 Newtown. That there ironmongers shop [Elmer’s] weren’t there then.

Newtown in about 1905. I think Billy lived in the small cottage on the right which by this time had become Widdup's shop. Notice that the street isn't paved with setts.

What did your father do for a living Billy?

R-Well he used to weave at Wellhouse when Old Billycock had it up to Robinson Brooks starting in Clough. There were 400 looms in Wellhouse I know, I can tell by the roof where they were and t’other were all spinning. Butts and here. Billycock lived at Newfield Edge.

Newfield Edge in 1910.

Well I can tell they had two beam engines at Wellhouse, they’d one for this wing and one for that. There’s a tank on top of one of them [engine houses] now. Well I used to watch the governors going round on this wall side, it’s chopped off now to build a shed. Them governors were old fashioned ‘uns they went like that and I used to stand watching it through the window when I were a lad you know, I’d be four or five year old. [1886/87. Wellhouse was built in 1853]

Wellhouse Mill in about 1892. You can see where one engine house has been demolished on this end of the mill and half way down the multi-storey range the tall windows mark another engine house.

They pulled them engines out in about 1895 didn’t they? [demolition was 1890 and [the new] engine was installed and started in 1891. Calf Hall Shed Company bought the mill and one condition of them buying it from the Craven Bank was that the bank demolished the old beam engines and scrapped them. CHSC had to build a new engine house and install a modern engine. This was to safeguard the bank loan, if CHSC failed they wanted to have a modern mill to sell.]

R-Aye, well I can tell of ‘em dismantling ‘em and chopping them storeys off. You can see the wall boxes in the wall where the shaft used to come through. I used to go down wi’ a truck for a hundredweight of firewood for ninepence, we used to go to the gasworks to weigh it. Aye, oh my God, pitch pine window sides, pitch pine, it were grand stuff. We used to go down wi’ trucks us lads you know, ninepence a hundredweight, aye.

Did your mother weave Billy?

R-No, she came from down South. Now me dad worked there [Wellhouse] as a weaver first, he were cousin to Robinson Brooks you know. You see they were all one family. Now when Robinson Brooks started to weave in Clough Shed he went weaving there up at Clough because this finished. [Wellhouse was closed after Bracewell Brothers failed in 1887] Now when they went down to Long Ing we were coming on wi’ three or four of a family on us. Robinson said [me dad] he mun learn to tackle, so he learned to tackle and he had a little set you know, he’d happen make about thirty bob a week then, I don’t know. Now when he’d getten a family of about six and Brooks had got a tape, he were for giving up and going to Earby to start on his own so Robinson Brooks said now then Jim, tha’s got a lot of childer, we’ll get thee learned to tape. So Thomas Henry that were leaving learned him to tape you see for two, maybe he charged him £2. So he taped at Long Ing until 1911 and when Robinson Brooks went to Westfield and got 900 looms, it wanted two tapes then. He gave over you see, he didn’t want to go he said I’m not going to work in a shed, there’s no windows at t’side. They were at the top, he said I’m not going, it’s like a prison is this. Well, he were reight you see, they had them there does, [north lights] Well says Robinson, they’re modern! It’s lighter! But you know you couldn’t see owt. He he he! [Quite a common complaint, workers liked to see the outside world]

So what did he do then Billy?

R- He worked, well, he went weaving a bit, aye. Off and on like Aye, he used to go on’t spree a bit and he’d be off a while, him and Tom O’t Edge happen, aye. Me dad worked at Widdups down at Moss and Old Tom O’t Edge were beam to beam to him, did you ever know Tom O’t Edge?

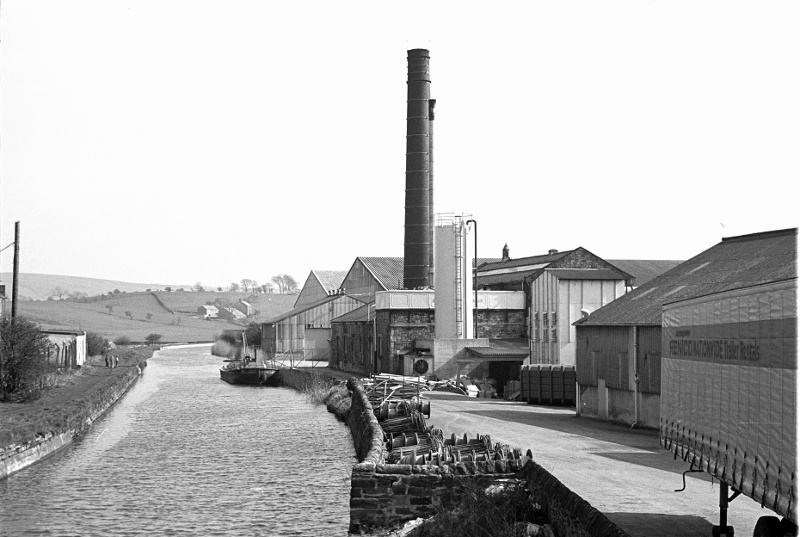

Moss Shed in 1978.

No.

R-He were, he he he! They used to go on’t spree you know, nobut twopence a pint then. Me father once, me father went , Christmas was nobut a day then, just Christmas Day, there weren’t no Boxing Day holiday, you worked on Boxing Day. Well he set off, me mother says yer father’s gone to his work, by God he’s done all right. Well, he landed back. Me mother says what’s to do? Well he says, Tom O’t Edge hasn’t come to work! When he saw Tom hadn’t come he turned round and comes out! Ha ha ha! There were some pubs you know, in them days, they were open all day and they used to go on’ t’spree a lot of ‘em and they were in all day from morning till night.

How did they manage to afford that Billy, did they save up or what?

R-Well you know, twopence a pint, they’d get six pints for a shilling. You know if they got a couple of bob off their wives, well, they’d twelve pints you see. Their wives ‘ud happen give ‘em a couple of bob you know wi’ a bit of playing heck and all sorts you know. They’d work regular and happen be nearly teetotal you see while they’d saved up a bit of brass you know. Happen a couple of pound and then they’d blow the lot, aye, and happen strap a bit as well, aye. Ha ha ha. ['Striking t'rant']

How many children were there Billy?

R-Eleven and there’s six living yet. I’m the eldest of the eleven. Me sister’s eighty six and the next is eighty four, me brother and me next sister’s eighty and me brother Ted’s seventy eight.

Aye and when you lived in those cottages on Newtown there, Albert Road wouldn’t be built.

R-Oh no, Just where Elmer’s ironmonger’s shop is on the corner there were a big wall and a gate and Spen Thornton and Sam Heap had some land there which was a plasterer’s yard wi’ all their drain pipes and all sorts, and it were railed off and all t’other was a field right up to the station. Now this side, where that there fancy shop is wi’ all that stuff in it you know [The Occasion, opposite corner to Elmer’s] There were a laithe [barn] there and a slaughterhouse next to it and they used to kill there you see.

Who ran the slaughterhouse Billy?

Wellhouse Farm in 1881.

R-Well, before I knew owt it were a [William] Baldwin [1871 census, William Baldwin was 49 years old, farmer of 16 acres employing one man. Address was Wellhouse Farm on Church Street.] but in my knowledgeable time it were the Cooperative there were a chap called David Raw, his brother were John that had the farm opposite old Coates Mill at that time. John and his brother David used to kill there, aye. Now us young ‘uns, at t’back there were a yard and we could see reight into that slaughterhouse and we used to watch ‘em pull ‘em out wi’ ropes out of the shippon and it used to take two or three to pull ‘em out. They used to pull t’nose down to a ring in the floor and they had an axe wi’ a do on the end about like that, [Billy describes a poleaxe] and they used to hit ‘em here [indicates middle of forehead] and they used to miss sometimes and hit ‘em in the eye. Aye, it were a pity to see them.

What sort of a going on did you have when you were a child Billy? Were you hard up when there were 11 of you at home, they must have taken some feeding.

R-Well, when we got to eleven I started earning a bit you know and me father addled [earned] about 35 bob a week.

That ‘ud be a good wage then?

R-Aye, but I don’t know how she managed, course they all used to get in debt a bit. The Brooks family, they were old fashioned grocers where Greenwoods tailors shop is now, Greenwoods. [Chris Brooks and Son of 23/25 Church Street in Barrett’s Directory of 1887. In 1871 census they are on Newtown and described as Christopher Brooks and William Proctor Brooks aged 18 shop man, grocers and drapers.] Brooks had that, Robinson Brooks old father (Christopher?) they started there and they’d supply you wi’ owt, they were old fashioned grocers. They’d supply you upstairs wi’ a pair o’ breeches for childer or owt. Now you allus had a shop book you see. If you couldn’t pay it all it went on to another week and they were never straight while they got their childer up [Grown to working age], course they’d clock sommat down for interest you know. Well there were lots of big families in Barlick at that time and they all got into weaving and then they got straight and bought their own houses you see. That’s how they did it, aye.

Can you remember much about the house in Newtown Billy? How many rooms were there in it?

R-There were two bedrooms, a kitchen and a living room.

How about carpets and such? Did you have carpets in those days?

R-There were no carpets at all, nobut a rug, a peg rug and they were all flag floors and they used to get sand, Aye, all sprinkled wi’ sand and when you were walking about wi’ clogs on they used to crrrrrr on the sand, aye.

Can I ask you a few questions about your mother and the house?

R-Oh aye.

Can you remember any of the furniture Billy?

R-Well there were an old fashioned table you know and an old fashioned chair for father to sit in and there’d be one or two old fashioned chairs wi’ them backs you know. Didn’t bother bout furniture then, there were no furniture. There were them old fashioned mahogany drawers you know, about that high. [Indicates about 3ft6”] You know wi’ big wide drawers in, aye, they nearly all had them in those days, aye.

How about curtains Billy?

R-Well there weren’t much, there were more paper blinds in them days but there were like odd curtains. There were none of that stuff [lace curtains?] and they all had blinds wi’ a roller and they pulled it wi’ a cord you know round a bit of a wheel at the bottom.

How did your mother wash Billy?

R- Th’old do with a dolly, aye. You know in a big dolly tub. Aye, and an old fashioned wringing machine, wood rollers. Isaac Levi used to sell ‘em, they had his name on you know, big heavy cast iron. They were made in Keighley. There were a big shop at Keighley for making them.

You’d have the job of turning that with being the eldest?

R-Well I used to, but I don’t know, they weren’t that bad to twine [turn] considering. They were geared very fair, aye, they had a little wheel on the big handle , a little gear wheel you know and they went into big ‘uns. Well, it helped you on a bit you see. Oh aye.

What sort of a life would you say your mother had in those days?

R-Well, when I look back it were a hard life because you know there were all them mouths to feed. I wish I had a photograph, my sister has one where we were all on. [I had one] but I must have lost it, but she’s got one that’s framed, I would like you to see that. Aye, tis a grand ‘un. We were taken wi’ a chap… I’d be about nineteen and they were all on, me mother and father sat there, aye, I wish I had one to show you, aye. Well you know, we had New Years Day. Harry Slater that owned Clough, they lived across on that terrace, whatever did they call it. [Mitchell Terrace at the bottom of Barnoldswick Lane, now called Manchester Road.] We used to go up to Harry Slater’s at New Years morning for an orange apiece. Aye, we used to go back and come through a gap, aye. We once tried to go twice, Hey, you’ve been here before! Hop it! Aye, we geet an orange apiece.

They tell me Harry [Henry] Slater were a grand feller.

R-Old Harry Slater they called him. I know where he’s buried, he’s buried in Gill. He’s buried in Gill there down at the bottom, aye.

And he’d own Clough?

R-Well, aye, there were Fred Harry Slater, Joe Slater who had [married] Old Billycock’s daughter who lived at Newfield Edge. Ada. Aye, he lived there, well he were one of Slaters. There were Fred Harry Slater, he lived down at Carr Beck there, reight there going down to Horton. And then there were Bumpy [Humpy? Not clear but sounds like a by name.], another brother and Dick Carr Slater, he were another brother. Oh aye it were Old Harry Slater, I were very young when he died but I used to hear ‘em talking about him you know, and I knew all his sons, all the sons you know, aye.

How old was your mother when she died Billy?

R-I think she were 78 or sommat like that and me father died at 62.

Can you remember what year they died?

R- I just forget what year now. I haven’t a reight good memory for looking back to dates, I’ve to go and look at t’gravestones! He he he!

It’s as good a way as any Billy! You don’t do so bad, don’t worry about it.

R-I’ve a brother that could tell you that date to the day. I’ve a letter there frae him from Blackpool, he’s 83. Aye, we worked together, we had two tapes at Westfield, we worked together there aye.

How about school Billy? How old were you when you went to school?

R-Five, same as they do.

Which school were that?

R- Wesleyans on Rainhall Road.

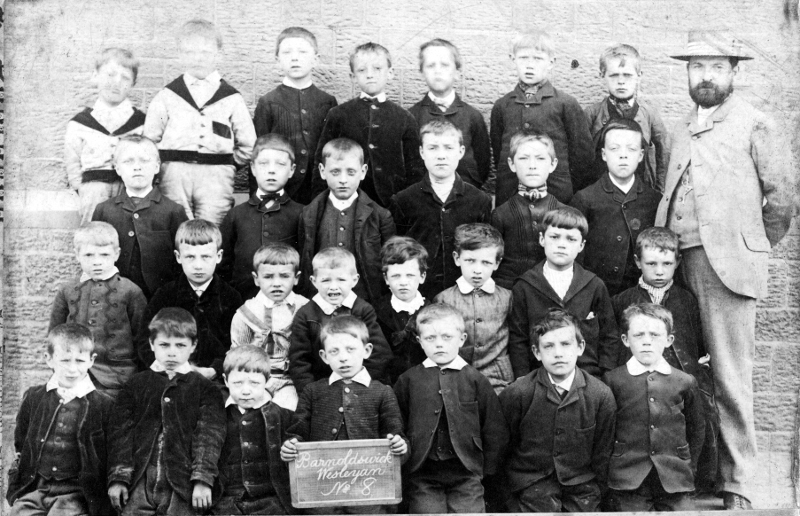

Wesleyan school.

Class 8 at the Wesleyan school in 1885. Isaac Barritt is the headmaster.

What were school like then.

R-Well of course it’s different in schooling today, I’ve been in a time or two, Miss Riding [Head mistress at this time. Billy used to go in to tell the kids about the old days.] made me some coffee one time. I said it’s eighty year since I started here, eighty five year then. That were four or five years since, they made me some coffee and I sung a song or two for ‘em that we used to sing when I were at school when we had Christmas concerts like. I said I were in the ‘Fat Boys’ aye. He he he! Aye, I’ve been in a time or two.

Can you remember doctors coming and looking at you when you were at school?

R-Aye, I can tell of that, aye. And when you got passed [for] half time you’d to go down to be passed wi’ t’doctor you know, in’t office.

Where did you go for that?

R-Down in’t mill. Doctor ‘ud come, Dr Oldland it were, he’d come down to the office and they send for you and you go in. Now then, he nobut looked at you you know, He says, Is this one of Jimmy’s? That were me father. Aye he says, He’s all right, aye, I can tell on him saying that. And that were it.

So when you started working you started at Long Ing, tenting.

R-Aye, tenting at half a crown a week, aye.

How long were you tenting?

R-Well, wi’ me uncle Will being manager, he were the cut-looker but he were a manager, he were uncle to the boss (Christopher), he were me father’s uncle really but I allus called him uncle Will. He had some hens up at Old Billy Nelson’s up at Clews. [Old Barlick name for Hill Clough up Esp Lane.] Reight up [Esp Lane] aye. Well he shoved me on for sake of [me dad] you see, he put me on to two loom afore I left [school?] afore I were thirteen, and he put another young lass to help me. She did mornings one week and I did mornings the week after and then she did afternoons and we joined at the brass you see. Well we made about eleven bob a week as a rule, we’d five and a tanner apiece. [Tanner=sixpence] Sometimes there were an odd halfpenny and she had the ha’penny one week and I had it the other. They called her Clara Pickles, she’s dead now. We joined at them two loom, me uncle put me on sooner than I should have for the sake of..[family]

How long were you on two looms Billy?

R-Till I were full time and then I got three at 13 years old. Then I got three loom, aye. And then when I were 15, after about a couple of year, I got four loom but I weren’t one [for working at it] I were allus playing about a bit but if I made a pound a week I used to get a penny in the shilling pocket brass, one and eight pence. [20 old pennies]

And could you make a pound a week on four looms then?

R-Well, a good weaver ‘ud make twenty four bob on four loom you know but such as us, we were always tinkering about wi’ keys and all sorts you know, we’d do owt but weave. Aye, well I got to be about sixteen years old I started to learn to tape with me father. At night when he worked over you see, and at dinnertime. Well, I could hardly lift a warp out you know then, well me uncle come up, he says He’s too young to lift warps out. Well, anyway, I went on and on of course. Me father and mother, they’d getten us all up then [reared the family] , they used to go to Southport for a week and put me on to do you see, aye, they had a week at Southport, aye.

And he’d leave you running the tape?

R-I run his tape.

How old were you then Billy/

R-Seventeen.

That were young.

R-Aye, it were young, aye.

You must have been a good man.

R-Well, I’d happen be eighteen or not so far off, I were alreight aye. Well, me father says to me, he says I’ve seen an advertisement where you can get a suit for 18/6 at Newcastle on Tyne and they’ll send you a form to measure wi’. (Did you ever remember anything like that?, I don’t think you, happen you wouldn’t.) he sends for a form and it showed you how to measure, eighteen and a tanner apiece, a suit, waistcoat an’ all. Well this form comes and I measured him you know, suit come and he put it on but it were a bit tight like. I said I think I’ve measured a bit short… Well, they were going to Southport for a week on the nine o’clock train in’t morning. Well, when they went up you know [for the train], me father called in t’Con’ Club you know, it were open. Your father’s going to be late, it’s time, train’ll be going, guard’s ready for whistling, he’s allus like this! Aye. Well father comes running round and you know, they had to step up into the carriages you know, off’t platform. Crrrrrrr! (sound representing tearing cloth.) It tore all t’way down! He he he! Aye. Course, they were made of shoddy stuff you know.

(Laughter from Stanley)

R-Me mother laughed, Eh, just look! There’s nowt to laugh at, isn’t this. Me setting off! She had to pin him up you know, to pin this do up, aye, she telled. Eh, there were some dos! Aye, in th’old days you know when t’Blackpool trip went at t’morning, you know, about half past seven you know. There used to be all th’old men about town you know same as Bill Sagar you know what built th’houses, they used to be there you know. They used to get cigars you know, aye, aye. They used to wave ‘em off you know, aye. Joe Standing and all them you know, aye. Oh aye, there were some characters in them days, they were colourful characters and they were amusing.

Holiday makers on Barlick station at wakes week.

They had hard lives an’ all Billy?

R-One Sunday morning I thought it sounds a bit funny, it were soon on, sounds to be a lot of carry on outside, there were a whole crowd out in’t road. And it seems that there were a chap called Dr McTackham [Billy’s pronunciation. Barrett for 1899 has a Rev. McCallum, a Baptist Minister, could this be him?] or sommat, he’d knocked a damn great top stone of that wall. He said There used to be a road here, reight onto t’canal bank. I’m barn to open it again, and he prised a big [stone] wi’ a crowbar. Well, t’police had to come and stop him you know.

Whereabouts was that Billy?

R-In Newtown. Aye, he he he! There used to be a road down here he says and I’m barn to open it out again, they’ve shut it up! Well he gets this crowbar you know, crash with this here, aye, there used to be some fun! At Saturday night when t’pubs turned out there were nearly allus somebody locked up every Saturday night and they brought ‘em down at Monday morning frae t’police station for t’first train to Skipton, aye.

To go up to court. What were drunk and disorderly?

R-Aye, aye. Eh aye. There were, o’course, we, us as youngsters, we used to make us own entertainment and us own amusement you know. We’d make a big ring in Newtown reight in t’middle o’t road and play at tops, you know, whip and tops. You put a top in there in the middle and we had to whip us top into the ring and if it stopped in that ring yours took it, took t’top aye. There were no traffic you see. We could play at owt in the road, ‘cause there were nowt coming you see, aye. Eh aye, we used to set off to Gisburn wi’ hoops you know wi’ a picking stick for a knock you know. And then we’d get old Stevie Parker [blacksmith on Skipton Road, Barrett 1902] blacksmith to put us a guider on you know for your…. Aye. [‘guider’ was a metal hook that you allowed the iron hoop to roll through and was used for steering] Oh happen twelve, twenty of us all set off to Gisburn aye, and back again, aye.

The main road to Skipton in about 1900. We forget now how safe it was to be in the middle of the road.

Can you remember any music at home when you were a lad Billy. Were there any musical instruments in the house.

R-Well there were in Barlick, a good band in Barlick at that time and me father were in it and he were the secretary for it aye. Aye, there were a good band in them days, all Barlickers, aye.

So your dad ‘ud play an instrument?

R-He played tenor horn aye. He’d be in the band twenty odd year aye, aye he were. I remember him going, when I were quite a lad, I were in bed and I heard the band playing through on Sunday morning, eh it did sound grand. They’d been in Scotland to a contest and they’d landed back to Skipton and they came by wagonette you know, to Barlick and they played through at about seven o’clock in the morning, it were dark you know, aye, grand. I remember all them does aye. They used to have a flower show down at Brick School, it were all fields in them days.

The Brick School on Fountain Street.

What do you call the Brick School Billy?

R-Oh, it’s Ouzledale Club now you know at Fountain Street. Well, before them houses were built it were a field and they had t’flower show in there and there were a band contest. Black Dyke Band come once, aye, about six or seven bands marched through the streets there wi’ a board up wi’ their name on and that were about, I’d be about six it‘d be 1888. I remember we lived there, they all come playing you know, aye.

So you’ll remember them building Albert Road?

R-Oh yes, there were a field there.

Those ‘ud be houses then wouldn’t they Billy.

Albert Road in 2005. The shop with the clock on the gable used to be Sneath's.

R-All houses bar that shop at the end that Sneath has, at this end. [John Sneath, hairdresser. Barrett 1902. Now Nutter's newsagents in 2000] That weren’t made into, it were built as a shop aye, they were all houses there, Bill Sagar built ‘em and he built Ivory Hall an all. Sagar’s Chambers they’re called. There’s a door if you look, if you go up Brook Street there by Redman’s you’ll see Sagar’s Chambers, Bill Sagar built them, aye, aye. Oh aye, Joe Standing built some houses up here [Cornmill Terrace area?] I think Proctor Barrett built these and that row across there all of them, Proctor Barrett, course you wouldn’t know them.

The Ivory Hall working men's club (built 1899) and Sagar's Chambers in Brook Street in 1980 shortly before demolition.

No, Proctor Barrett, I know a fair bit about him, he was one of the main men at the Calf Hall Shed Company.

R-That’s reight.

Aye, a bit of a case were Proctor I should think? From what I’ve heard about him you know, from what I’ve seen written down about him, he were a bit of a sharp lad were Proctor weren’t he?

R-Well, they were old fashioned ‘uns in those days. Proctor, he were a big church man, oh aye, he were.

SCG/09 December 2000

5393 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 78/AB/2

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 19TH OF JULY 1978 AT 17 CORNMILL TERRACE, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS BILLY BROOKS AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Aye

R-Is it on now?

Aye.

R-Is it?

Yes, it’s only like a loom Billy.

R-Aye.

There’s one tape recorded while you’ve been talking to me.

R-Oh have you?

Aye, don’t worry about that thing.

R-Well as you and me’s talked about the cotton trade I sit thinking sometimes and me mind goes back to when the cotton trade what you mun call its infancy you see. In fact I had relatives who used to weave cloth in their houses and they had to take pieces to Colne to be paid, in a wheelbarrow or owt. I’ve heard me uncle Will [Father’s uncle actually] tell about that. He said that he lived in Newtown and when they finished a piece they used to wheel it to Colne to get paid. Well, t’cotton trade of course it started that way, that ‘ud be early on in’t happen 1790 when it were, up to about 1820 when they started a building mills you know and run ‘em wi’ power. Power looms, and folk rose up in arms again that, they said it ‘ud do ‘em out of a living if they were barn to , you know, have these here engines and looms going. It’d do ‘em out of a living at home bit it, but instead of doing ‘em out of a living it made ‘em more you see. Aye, they even went round in gangs at drawing plugs out of the boilers, they called ‘em plug drawers in them days, that were happen about 1830, at 1790 and 1800. They called ‘em plug drawers, of course this is knowledge that I get off me grandfather you see.

You can remember your grandfather then?

R-Aye, aye. Well of course time went on you know and Barlick were dependent on the cotton trade, there were just Clough and th’Old Coates Mill you know, that’s all there were and Old Billycock in them two mills you know, [Butts and New Mill, later called Wellhouse] Well, they closed down [post 1885 when Bracewell died] and Barlick, there were practically grass growing on the streets, aye.

Tell me something Billy, when Billycock died, why did they shut Butts and Wellhouse?

R-Well you see, I think his son weren’t much good [Christopher George Bracewell of Bank House, Coates] he lived up at Coates Hall. [Billy has this wrong] I don’t know whether he didn’t drink himself to death or not, there were sommat, I just remember sommat. They called him young Billy or sommat and, no, whatever did they call him? But I don’t think he were any good at business at all so it, you know, there were nobody to take ower that were reliable. I think that he were a bit of a rake, of course I were a bit young then [Seven years old, CG Bracewell died 11th September 1889 aged 43 years leaving a widow and four children. Buried at Gill in a new vault built by E Smith. Undertaker was Proctor Barrett.] you know and didn’t take much notice. It runs in my mind that there were sommat like that, that he come to an end some way. Anyway, so of course there were practically grass growing in the streets in them days, there were nobut them, Clough and them looms, Brooks geet some looms and Pickles and them and then there were four hundred at Coates and they were lit up wi’ oil lamps were Old Coates in them days. [Billy must be talking about New Coates because Old Coates was derelict in 1889.] Aye, and them’s all there were.

Who had Coates then Billy?

R-A firm called Bell and Company frae Manchester, they were cloth agents, aye, Bell and Co.

And they owned it?

R-No, I don’t know who owned it but they used to run it, whether they owned it I couldn’t say. [Probably owned at that time by James Nuttall who built the mill starting in 1864 but delayed by shortage of capital so I’m not sure of the actual start date.]

Can you remember anything about Old Coates Mill Billy?

R-I can tell on ‘em pulling it down.

When were that, any idea?

R-Well it ‘ud be, as far as I can tell I think I should be about ten year old when they pulled it down [1892] No, I might have been, aye, about ten because I used to go down there and look at where the old water wheel were. Now there were a chimney and there’d been an engine in and the chimney were like a sort of falling down. It weren’t a big chimney, no there weren’t much, square one and there were four storeys and John Raw, that had that land, [Farmer at Coates Farm, Barrett, 1902] he used to store his hay in there. He stored his hay in there off them meadows there round about. And then it were pulled down. There used to be a dam wi’, where Rolls has their car park now, it used to run that water wheel, oh aye. I can tell of Old Coates mill that Tom o’th’Edge used to tell the tale about working there when he were a lad and he said they used to go in of a night and set the waterwheel on so as they could weave a bit for a bit of pocket brass. Aye, they used to go and set it on their self, aye he did, aye. Ha ha ha.

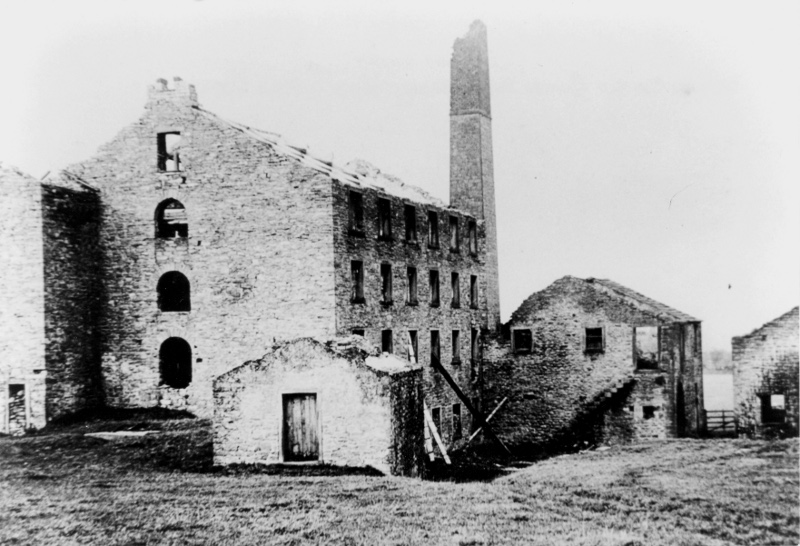

Another view of Old Coates Mill in about 1890.

Aye, to get a few more picks.

R-Aye, he says We used to go down and turn t’water on and weave a bit. Aye, they wanted an extra pint or two you see, aye. Well you know, it looks to me that that would be about 1850 when that mill were built or 1830, mmmm. I think happen it ‘ud be built happen at beginning of cent, 18th century. [Billy is obviously wrong here, it was earlier but the gist of what he says rings true. 1830 to 1850 sounds about right for water-powered weaving]

Aye, happen so.

R-Oh I can picture it, all t’windows were out you know.

Aye. When your granddad was on about hand loom weaving, did they say anything about where they got their weft from?

R-Well I think it were brought round you know frae them that let you t’job you see.

Aye.

R-They’d bring you t’weft you know, same as in Bradford and there, these tailor firms, they let work out for tailors in their own homes and they take them the stuff. I think it (the weft) ‘ud come round I think, me uncle used to tell me , I’ve heard him tell about him and his sister and me grandmother when they were young you know. They used to weave in the house and he once telled me about going to Colne wi’ a wheelbarrow wi’ a piece on, aye, to get paid.

Can you remember seeing a hand loom in Barlick?

R-No. I don’t think so, no I don’t think I have, I don’t remember if I do. No I think they’d getten all, I might have done and forgotten you see.

Yes.

R-Well you see t’cotton trade, as I said, in Barlick, it depended on’t cotton trade, there was nothing else and t’Calf Hall Company were formed and they bought Butts but it went under the name of the Barnoldswick room and Power Company, that were it’s first name [ CHSC started when they built Calf Hall Shed in 1889.] It bought Butts and Wellhouse and partitioned them off into 400 spaces you see and that’s how Barlick started growing. Aye, the cotton trade were sort of coming on and then Moss were built and Barnsey were built and t’Fernbank were built. Now t’cotton trade in Barlick had getten to it peak then and it got ower the top and started steadily declining after that.

When would you say the decline started Billy?

R- Well it ‘ud start declining of course a long while, it ‘ud be about, it started declining slowly about 1940 or somewhere there, slightly but it worsened as time went on and they couldn’t get orders that ‘ud pay and there were part short time come on you know. And then the government decided that it ‘ud be better if a lot of firms went out and it ‘ud be better, and it ‘ud enable them firms that were left in to keep going and they paid ‘em so much if they’d come out and break their looms up. They’d give ‘em so much if they’d come out and they could have scrap iron price for their selves. So a lot of firms decided on that and they paid ‘em so much a loom. Well, that eased things a bit for a while and then of course it worsened again and then there were wholesale stoppages. Then they brought that redundancy law in where they had to get paid you know where they never got nowt before. And then, well, it gradually declined till there were three quarters of ‘em out. I went to Rushworth’s once and they’d slays the height of a mountain in their yard, slays.

At Colne?

R-Loom slays, aye. [Billy is right about this. They had one pile of scrap looms at Primet Bridge as high as the viaduct and another large pile at a mill on the bottom road in Colne. Local legend says they closed their gates during a royal visit to Colne and that they were paid by the government to maintain a stock pile of cast iron scrap as a strategic reserve.]

And you say that Rushworth’s from Colne, they were shareholders in Long Ing Billy?

R-They were, aye and they supplied all the troughing and the pillars.

When were it built?

R-In 1888 and 1890. They used to come ower Tubber Hill with a traction engine and a chap waving a flag at t’front, he walked in front of it, aye. And us school children used to go and look, Hey! Road engine’s coming, we could hear it a mile off, sh sh sh sh, aye. Aye, I can tell on ‘em laying the foundations at Long Ing when I were five or six years old. I can tell of going down a watching, a seeing you know, making them pillar beds. You know I can just imagine it.

All dug out be hand Billy?

R-Aye, there were none of these…. There were nowt o’ that, no. No they used to get through it. Aye, there were 1200, three four hundred loom [sets] there.

When you were working at Long Ing, how strong were the union Billy?

R-Well they were amalgamated to t’Northern Counties you know and Barlick, wi’ being on a branch line, they had a bit of a do of their own, Local Disadvantage. They paid a bit less you see but after a while they wanted to do away with that. They wanted it, it wouldn’t be above thruppence a week to ‘em you know but they went on strike for that. Tanner a week it made difference happen. And t’Northern Counties of course had to muck ‘em out you know. They brought Long Ing out first, best shop I’ Barlick, they brought them out first. Well, as time went on, folk come out of Lancashire and they get filled up, aye.

[Local Disadvantage was a situation initially agreed by manufacturers and unions whereby if a town had higher expenses by reason of being remote from the mainstream of the industry, both wages and room and power rates were lowered slightly to preserve the manufacturer’s competitive position. By ‘folk came out of Lancashire’ Billy means weavers seeking work who came to Barlick to take the looms at a lower rate, in effect, strike-breaking.]

How long were they out?

R-Well, they brought Butts out next you know. It went on for a year or two. If you come out of Lancashire and they [the union members] saw you they’d offer you ‘loom pay’, two bob a loom, eight bob to keep out, what they called loom pay, aye.

Who paid the ‘loom pay’?

R-Northern Counties Textile Association paid it, aye.[I’m not sure about this, the Northern Counties Textile Trades Federation was founded at a meeting on 10th of February 1906. See ‘THE LANCASHIRE WEAVER’S STORY’, a history of the Lancashire Cotton Industry by Edwin Hopwood. Published March 1969 by the Amalgamated Weavers Association. I think Bill means this association which was founded in 1858 and reorganised in 1884.]

So the unions were paying Lancashire weavers to keep out of the town?

R-Well aye, well these that come into the town you know, they, the unions in Barlick, if they saw them they’d offer ‘em loom pay you see, not to start.

So that they wouldn’t blackleg.

R-So they wouldn’t start but they all, eventually it all fizzled out, they [the mills] got filled up and they had to go back, aye. Aye, under the same conditions as they come out. Now, after that, these that had come out on strike, they [the manufacturers] wouldn’t have them no more you see, they black balled ‘em. Manufacturers had an association of their own. They had to flit out of Barlick to Nelson, up and down aye. Folk had come out of Lancashire and filled them up you see. I know one chap as I tented for a bit, him and his wife had ten loom making a reight nice do, reight narrow looms, 38” looms and they came out on strike. They wouldn’t have ‘em back and they had to go working in Chatburn aside o’ Clitheroe there, pity aye, pity that. Nice couple they were an all but they wouldn’t have ‘em back.

Was that fairly common Billy?

R-Aye. Oh aye, there were whole families of weavers had to [leave], couldn’t get [work], they wouldn’t have ‘em back.

And what about the temper of the weavers then, you know what I mean, they were obviously fighting hard were the weavers, were they bitter about the job? You know, did they…..

R- They were bitter at t’time you know and they used to boo in the street when t’bosses came through. Boo..ooh..ooh you know when they used to see ‘em, aye. Oh there used to processions through Church Street wi’, well it had gone off Long Ing then you know. And it had shifted [to Butts] but us young ‘uns we used to go and walk through for us to be bood at you know. There were folk, they’d old pea boilers and all sorts they were bumping through the street, owt. Old tin tanks and all sorts. Bill Crew that used to hev peas [ cheap fast food], he’d one or two old pea boilers that were buggered you know. They’d go and ask him for ‘em and they were braying ‘em through the street you know when the weavers were coming out of Butts you know. Aye, they were all mixed together through the street. We used to go and fall in you know, it suited us.

What year were that Billy?

R-I’d be about fourteen then.

So that ‘ud be about 1896?

R-That’s reight, that’s it, aye. [Billy is spot on with his dates. See ‘Lancashire Weaver’s Story’ by Hopwood page 58]

Can you ever remember there being any real trouble Billy? You know, police called out and what not?

R-Oh aye, police were in the engine houses aye. In Long Ing there were two policemen and slept there two year afore it, aye, they slept in’t engine house.

That were to stop sabotage like?

R-Aye. Well, Bradley’s that were in’t Butts at far end, where Carlson Ford is now, they’d 400 looms and then they flit to Bankfield when it were built. There were somebody slashed all the warps one night, they’d cut ‘em through, slashed all the warps that depth. [indicates 2”] Aye, all t’lot during the night.

Because they were working?

R-Aye, that’s reight. Aye, I remember that, mmmm.

Yes because I remember reading somewhere, well I’ll tell you where it was, it was in a book the union brought out called ‘The Weavers Knot’ [ I had this wrong it was THE LANCASHIRE WEAVERS STORY] I don’t know whether you’ve ever seen it. They said that at one time the police were brought in to Barlick and they acted so badly that there was a complaint made to the Home Office about them. I can’t remember the date now but I think it were about 1900. [1896 actually, same dispute that Billy is talking about. The Home Office replied that the police had only used 'reasonable force'.]

R-Well, the police come in you know and they [brought] mounted police once a twice for them does of a night. Well you see there were some rough ‘uns come out of Lancashire, there were some rough ‘uns come out of Lancashire, they were engaged to flay [dialect for frighten] folk to death so’s they’d stop out you see. There were that sort of thing went on.

So the unions ‘ud be bringing them in really.

R-The unions were paying them to come and intimidate ‘em. Aye, you see me mother and father and another dozen were down in Syke House {Foster's Arms public house] one night when they come in and started a [fight], you know, and police came and locked ‘em up and me father and him had to go down to Skipton and swear agin ‘em you know, aye.

When you say Syke House you mean Foster’s Arms pub do you?

R-Aye. Oh aye, there were all that sort of thing went on aye, oh yes. I saw t’cotton trade boom, I saw it get ower its peak and I’ve seen it decline, aye.

It’s nearly gone now Billy.

R-Well, I saw it. I saw it when it made rapid strides into a boom period. Although it were a trade were t’cotton trade where there were slack times when they weren’t buying on the Manchester Exchange, happen for a period and they had to go on short time. What they called short time and then it ‘ud start and bounce up again and they couldn’t do [make] enough you know, they couldn’t, and t’price went up because of the demand for the stuff. You’d go on a year or two like that and then there’d be another, it were allus fluctuating were t’cotton trade. Aye, aye, there were a tremendous amount of Jews in the cotton trade.

In the buying side.

R- I don’t say they were manufacturers, they were jobbers you know. They bought, they’d give you orders for cloth see. They weren’t, they didn’t manufacture it but there were a tremendous number of Jews aye.

How did most of the cloth go out of the town Billy?

R-Well it used to go out in cloth vans frae t’station.

By rail.

R-By rail. Down that wall side there, where you go into the car park [the wall backing on to the Fire Station] there were a rail all the way down there and there used to be cloth vans [rail wagons] all the way down there and they used to, lorries you know, they [the mills] all had a horse and lorry. They used to come up wi’ it at certain times, tha knows, and packed it in them lorries, them vans aye. Well, as time went on they all got motors of their own and you see, they’d go wi’ a load of cloth and then they’d call at the spinning company and bring some beams or stuff back the same night. That were so they hadn’t to wait on them coming to Earby and happen sticking there for a bit afore they got enough to bring down, you know what I mean. [Rail traffic for Barlick would be detached at Earby and wait in the sidings there until it was convenient to move the traffic up to Barlick, a delay for the manufacturers.] Aye, so that were an evolution that took place you see and then manufacturers started getting cars and before, they’d [The Manchester Men] get on a train at Barlick and have to get off, out, at Earby. They’d go to Colne and then get into the [Manchester} train at Colne. That [getting cars] saved ‘em bothering getting out at Earby and waiting of the train, they’d get it at Colne. Consequently the Barlick line lost that, they lost all that trade do you see. It’s a shame you know that that had to be pulled up. Big shame it is. Terrible, it’s a tragedy.

Yes, and when you were a lad that railway line, Barlick, t’railway line ‘ud be run wi’ Midland Railway Company wouldn’t it.

R-Well it were built wi’ Barlick Railway Company. But Midland Railway Company ran it for them you see. [Barlick Railway Co incorporated by Act of Parliament 1867. Under an act of 1899 the Midland Railway Co purchased the undertaking for £52,500. On 5th January 1900 investors with fully paid up £10 shares received £19-2-8 ½.]

Aye, something I came across Billy, when Calf Hall Shed Company bought Wellhouse Mill there must have been no water supply at the station and there was a pump used to pump water from Wellhouse Mill up to the railway station for the engines.

R-Aye well, there were a pump house down at Wellhouse there at t’back yonder. You’d hear, you could hear it puffing away, it were a steam engine. It used to pump water into t’dam frae out of that bore hole in the bottom, they’re filling it in now [the dams]. ‘cause they’re going to make a road through, it’s going to be an industrial estate is that land. If you want a piece of land and want to build a factory you can, you see.

Aye, was there a borehole down on Havre Park?

R-Well it were, you know where that decorators, Bolton’s decorators shop is? There used to be a pump there, just at t’side of there, there were a square wi’ railings round it and there used to be a pump in there but I never saw it working but I could, there were an old pump there. Now there were a bit, just down from there, down towards New Mill Dams as we used to call ‘em, there used to be a little well there, there were a spring there but they’ll have drained it now I expect, but I think there were a pump there, oh aye. Aye, I used to hear that pump puffing away, it were in a brick shed, it’s just getten tekken down this last year or two. I think Silentnight’s taken it down. You know they’ve … aye. But I used to hear it puffing away when I were a lad.

Aye, and when Calf Hall Shed Company took Wellhouse over they had a dispute with the railway company over how much this water ought to be and they stopped the pump. It caused a lot of trouble because there were no water for the engines at Barlick Station. [In 1905 in a letter from BUDC to the Midland Railway Company consumption was stated to be 32,500 gallons a week at 2/- a gallon]

R-No, no. Well at t’finish there were a water crane there weren’t there. It ‘ud be town’s water would that, I don’t know.

Yes. And when you were weaving down at Long Ing Billy, did you used to have to carry your own weft?

R-Aye.

Yes. And carry your own cloth as well?

R-Take your own cloth in and carry your own weft.

Yes. What were you weaving down there, what were you weaving on, those cops that you were using for your shuttles, they’d be old mule cops wi’ no tube in ‘em?

R-No tube in, no. There were no tubes in. We’d have thought it were a God-send wi’ the stuff that they use now. No, you’d to skewer ‘em.

Yes, and that was an art really wasn’t it, skewering a cop properly.

R-Aye, oh you had to skewer ‘em and aye. Sometimes you know in them skips they’d getten twisted all roads you know. Oh aye.

What did you do with your waste Billy when you were weaving, you know, in the early days when you started?

R-Well, at Brooks, you’d take your waste in at certain times and you’d tipple them on to a table and whoever it were, he’d look at them and toss ‘em up and turn ‘em over and happen say sommat or happen not and then he’d shove ‘em into a skip and then t’next ‘un ‘ud come and tipple them on… aye.

And if they thought you had too much they’d say something?

R-Aye, he’s say sommat. Anyone who’d made a lot of bad waste you know, when he’d finished taking waste, he’d [the person who had made the waste] go and dump it in that skip when he’d gone. He he he! I did that trick meself.

Aye. I’ve heard that the toilets used to get bunged up fairly regularly.

R-Oh aye, aye.

With putting waste down the lavatories. How strict were they? How strict were they with you Billy, the overlookers, you know like starting times and what not.

R-Well aye, in the old Billycock days if you look at that big entrance there [at Wellhouse Mill] there’s a little door at the side on it, have you noticed? Well they called that the Penny Hoil and if you were late you’d to pay a penny there and you’d get in and get back into the [thoroughfare, the main entrance into the mill] Aye, if you look you can see where the step were worn with clogs if you look.

The 'Penny 'Oil' next to the main entrance in to Wellhouse Mill in 1985.

Aye, that’s the doorway into Brown and Pickles’ office now, the Penny Hole because they have this end now, round the runway.

R-Well, it led back into the main do where…

Yes, it still does.

R-You see the [main] gate ‘ud be shut, you’d have to go in there and pay, they called it the Penny Hoil.

Yes. Now, about tramp weavers Billy. If you were late was there such a thing as landing in and finding somebody on your looms?

R-Well, there’d happen be three or four weavers waiting and’t manager of course. If it were somebody at…he’d use his discretion a bit you know and he’d go into t’shed and if they hadn’t come he’d say…. It ‘ud all depend who you were. If it were one that were customarily late you know, well he’d bezel [dialect word for penalise or punish] him but if it were one that hadn’t been late afore, well, he’d wait a bit you see, depends. I dare say in Lancashire they were a bit more stricter than what they were in Barlick, at that time.

Were they mostly women that were weaving then Billy?

R-Well there were as many men as women, in fact there were more men because in them days women couldn’t go to work, they had too many children you see.

And if you were off work were there any dole then?

R-No.

When did t’dole start?

R-I think it started about, it ‘ud start about 1930 I think or sommat like that. [Unemployment pay and sickness benefit was introduced in 1911 for certain trades]

Now my first pension were ten bob. [A bit of confusion followed here, Billy got mixed up over dates] Aye, when I were 65 it were ten bob. Aye it were five bob at start.

How did you go on on them days Billy, like round about the beginning of the century, 1900, 1910, if you got injured at work, if you were hurt at work, could you draw.

R-No there were nowt. No I don’t think so, I don’t remember, but there were no compensation then as far as I know. [WORKMEN’S COMPENSATION ACT. The 1897 Act made employers in certain dangerous trades including factories, quarrying, mining, railways and building financially liable for all accidents to workers in the course of their employment. Previously, under the 1880 Employer’s Liability Act they were only liable for injuries arising from negligence. The 1906 Act extended the principle of general liability to all trades and some industrial diseases.]

R-Now in later years Barlick formed one of their own. It weren’t, whether it were parliamentary orders that they had to… they had to have a private one if they wanted. Now of course it’s like, it’s national now you know. But at later years Barlick manufacturers formed a compensation of their own. [I think Billy is talking about the Barnoldswick Manufacturer’s Association here.] They had a secretary you see, one of their own lot and you had to apply to them if you wanted , if you had an accident you know.

And they wouldn’t be the best men at giving money away would they Billy.

R-No, he were a bit of a tight ‘un that ran it, aye. You’d happen get a pound a week, sommat like that you know.

Can you remember who the secretary was Billy?

R-Aye, Chris Brooks. Christopher Brooks, Westfield.

When you were down at Long Ing, weaving down there, can you remember any women ever bringing their children into the mill, like when they were breast feeding, and bringing them into the mill so they could have their children with ‘em and run looms at the same time, would they let them do it?

R-No, I never saw that. These women that were feeding their breast children somebody minded ‘em for about four bob a week. And they’d go up possibly at dinner time and let ‘em have a suck and then they’d go back for them at night. I never saw them bring ‘em into t’factory, no.

Yes, I’ve heard of it but I don’t think it happened so often.

R-I don’t think it happened, never, I never remember it. It might have done in later years I don’t know. I don’t think so.

When you were down at Westfield Billy taping, what sort of tapes were they?

R-Butterworth and Dickinson frae Rosegrove.

What were them at Long Ing, were they Butterworths?

R-They were Howard and Bullough’s from Accrington.

Aye, Howard and Bullough’s. That’s what we had at Bancroft. What did you use for your size Billy?

R-Sago flour and tallow. China clay, wheaten flour, sizing flour aye, but they give over using china clay after I left and flour and all, they just used sago flour.

Sago flour and tallow, that’s all we use now. [At Bancroft]

R-Aye. We used to put china clay in, it used to dry the damn twist up.

Aye, put a bit more weight in it Billy.

R-They were like flour millers sometimes, aye.

During the First World War can you remember, were things ever bad for food during the First World War you know?

R-Well, aye, Well you know you were rationed you know, with everything. You got coupons you know, you’d only ten pennorth of meat a week. Ten pennorth of meat a week, that’s all.

So that were rationing in t’First World War?

R-Aye, first, aye. Now Second World War, I were in a Blackpool boarding house and we used to do very fair there wi’ a bit of dodging, aye. Aye, they used to come wi’ their ration books you know and I used to take coupons out you know, if they hadn’t been cancelled before they come and I used to spend them and I had ‘em allowed for through the Food Office you see. Aye, I used to go out with these coupons, I used to get a load of stuff and then at the quarter end I used to send in me returns, I’d getten rations for ‘em. You see they granted us at our house, they granted us rations for thirty people you see. Well, if you’d nobbut twenty six folk coming I’d draw t’lot and then you used to send your tea coupons up and I’d put down ten more than there were and it used to come off, but one time it didn’t and they wrote back and said you’re ten coupons short, he he he. ‘Oh, that’s what I used to…..’ And then they allowed you a hundredweight of sugar to make jam on. Well we never made jam, we hadn’t time to bother making jam. A damn sack of sugar used to come, aye and about half a dozen cases of that there evaporated milk, oh yes.

How did you feed when you were at home on Newtown Billy? Were there plenty to eat?

R-Oh aye, they used to mek th’old do, sheep head and offal stew and all sorts. There’d be bowls of stew in’t cellar wi’ that white fat on top. Sheep head and offal mixed, reight grand stuff aye. And then at baking day at Thursday there were a tin of black pudding about that size, about that depth, black pudding, brown crisp at t’top and it were cut in squares, see, thirteen wi’t father and mother. Aye, By God it were good were that.

Aye well, you’d be handy to the slaughterhouse for the blood.

R-Geet pig’s blood! I went for pig’s blood oh aye. And then they’d get cockles and mussels for tea once a week. Two quarts of cockles and mussels, they used to come round wi’ ‘em in a barrow. ‘Cockles and mussels alive alive o!’ You know I’ve heard all that. Aye.

They would come in on the train would they?

R-Ah yes. Aye they used to come in sacks on the [train], they used to tipple ‘em on the platform, you’d see ‘em on [the station]. There were a chap called Tom Brown, he were a greengrocer, by God he had a voice, they could hear him up Weets of a quiet morning. If you were on Weets you could hear him in Barlick shouting, hey, what a bloody voice, ‘apples and oranges!’ Tom Brown they called him, eh God he had a voice! Aye.

How about chapel Billy, were they chapel-goers your parents?

R-Oh aye they were. Aye, all the chapels were fairly well filled in them days, aye they were. There were some good singers used to come at what they called their choir sermons you know. Eh there were some! Wesleyans, Walter Lawley, lovely tenor singer, they were packed out. There were a certain rivalry among churches who gets the biggest collection, aye and there were a certain rivalry at Whit Monday who had most scholars walking, they counted ‘em. Baptists used to have the most. Aye, Bethesda Baptists.

Aye, which chapel did you go to Billy?

R-Wesleyan.

Did your father go?

R-No

Your mother?

R-Well, she hadn’t the time, she never went though she used to be in the choir afore she were wed but of course she never went but she made us go. We’d to go to Sunday school in the morning at nine o’clock and then go across into the chapel while twelve.

When you went to Sunday School did they ever teach you anything apart from, you know the Bible and what not?

R-Oh aye. Well I don’t … the superintendent used to do most good because when we were in those bits o’ classes you know, I don’t remember ‘em saying anything much about Jesus Christ or anybody else but t’Superintendent ‘ud give an address that we used to be, you know, aye.

Whit walkers in Barlick in the 1960s.

SCG/23 December 2000

5963 Words