TAPE 79/AD/10

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 16TH OF JULY 1979 AT 16 COWGILL STREET, EARBY. THE INFORMANT IS HORACE THORNTON, TAPER AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Tape 79/AD/10

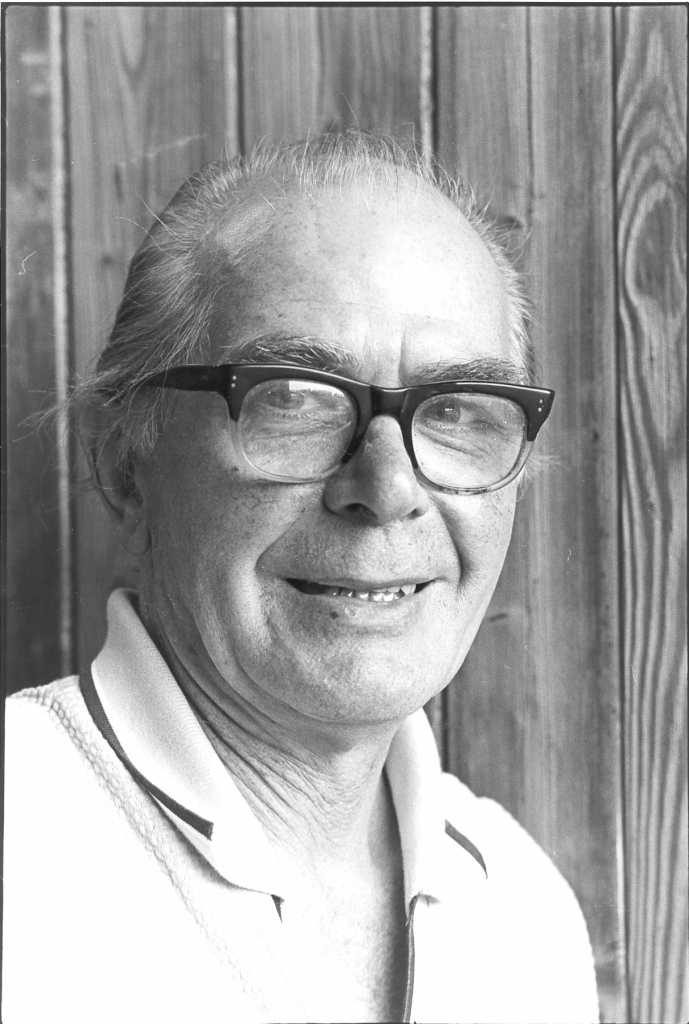

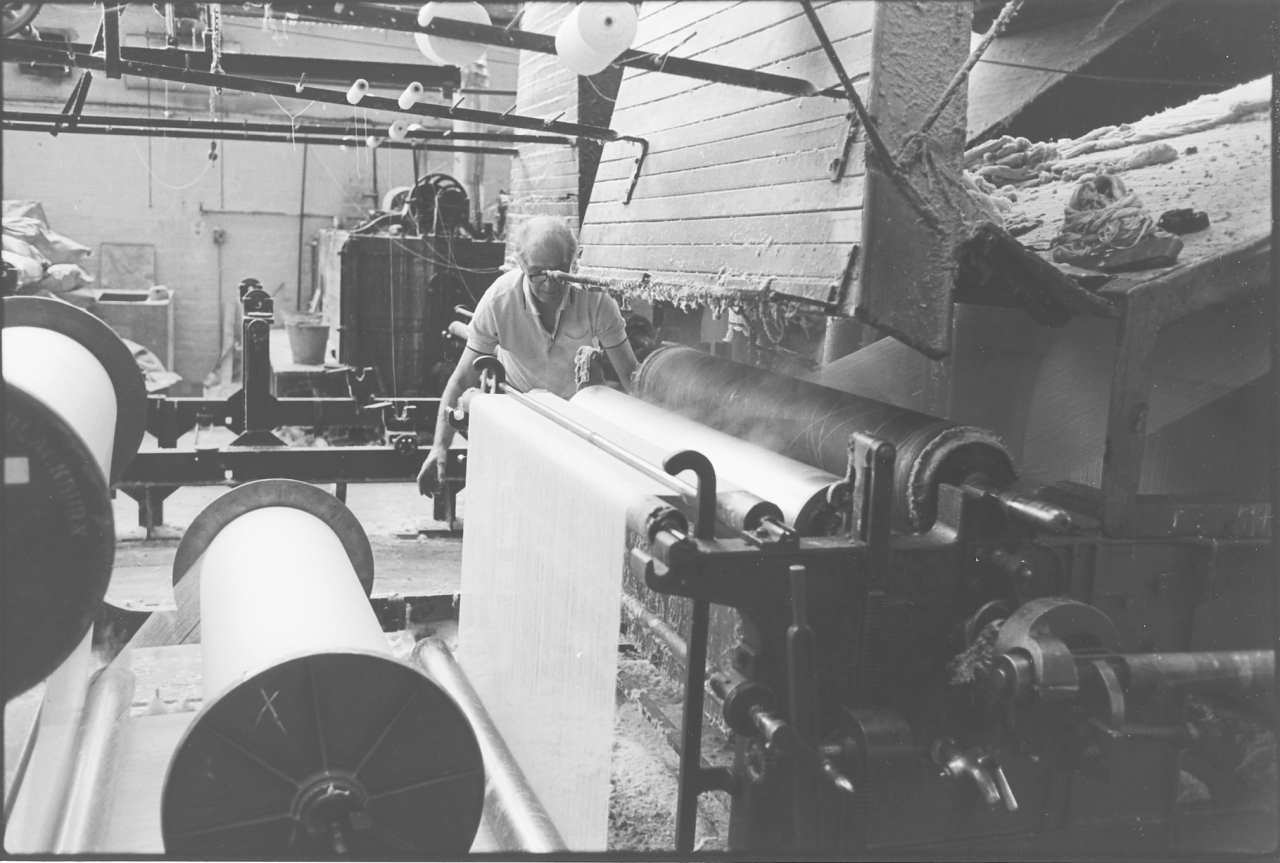

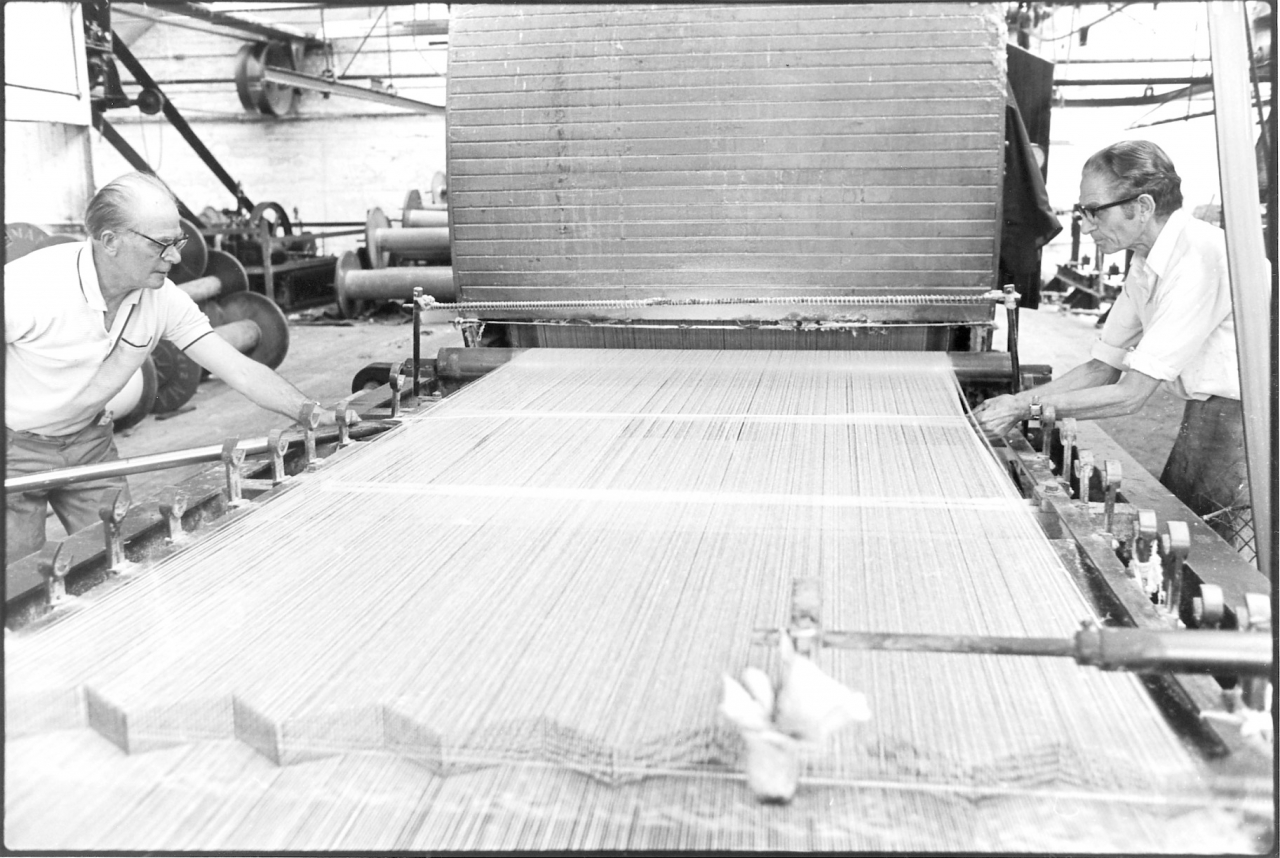

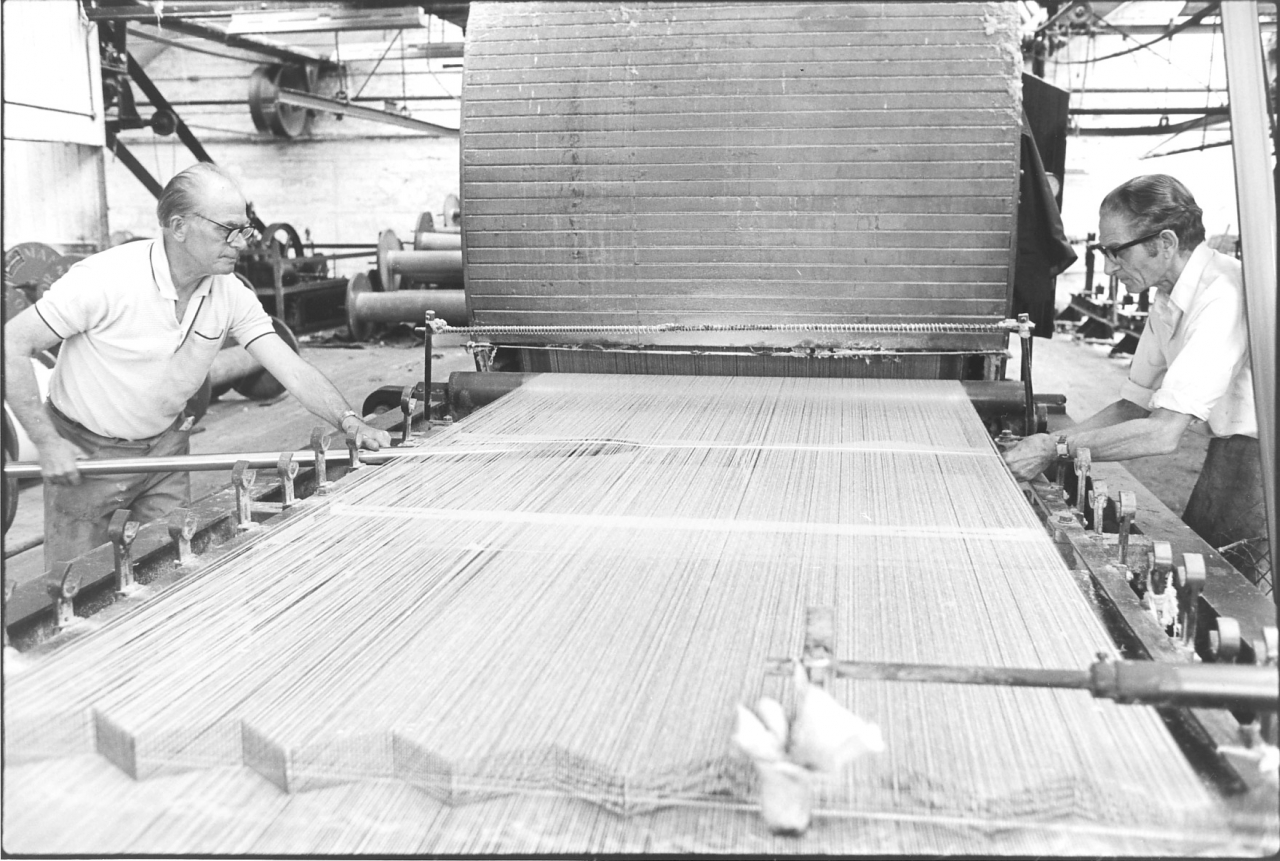

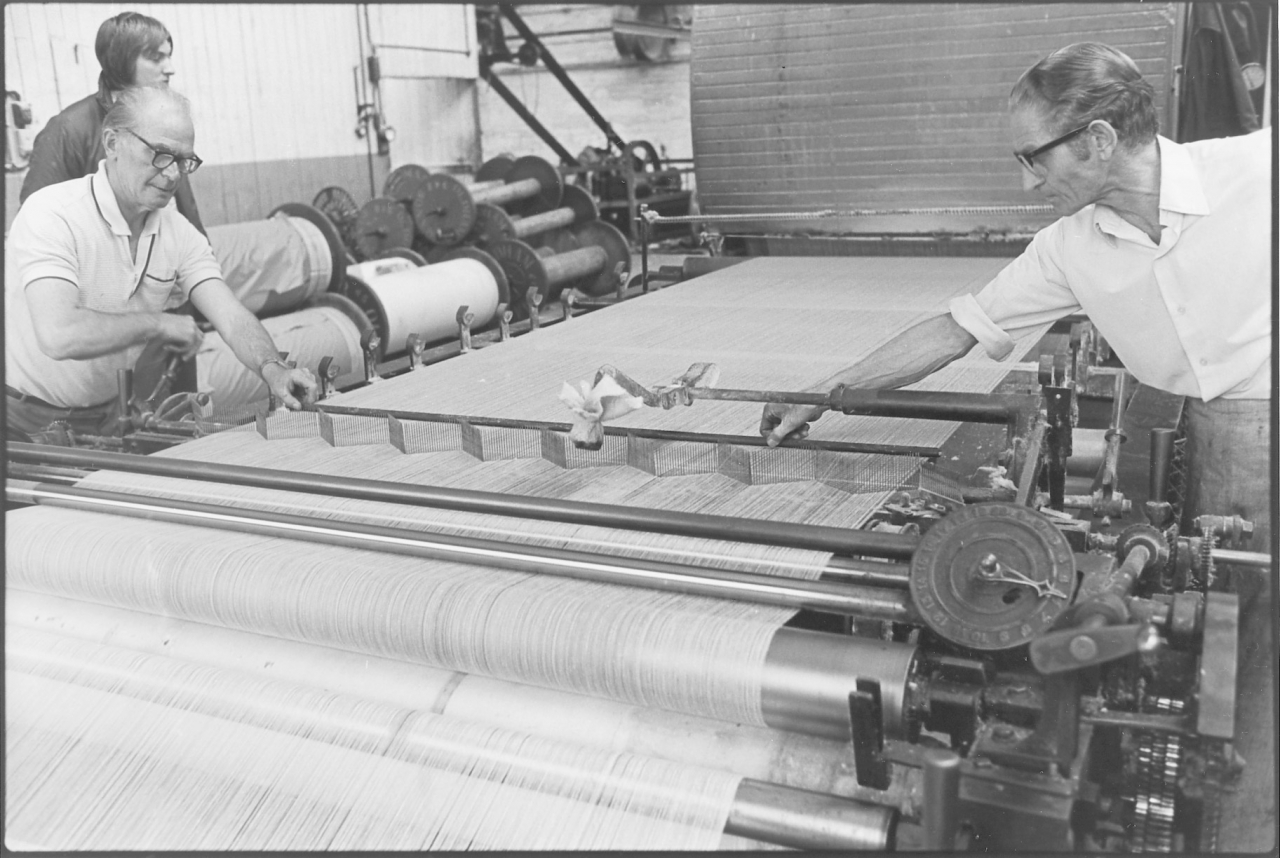

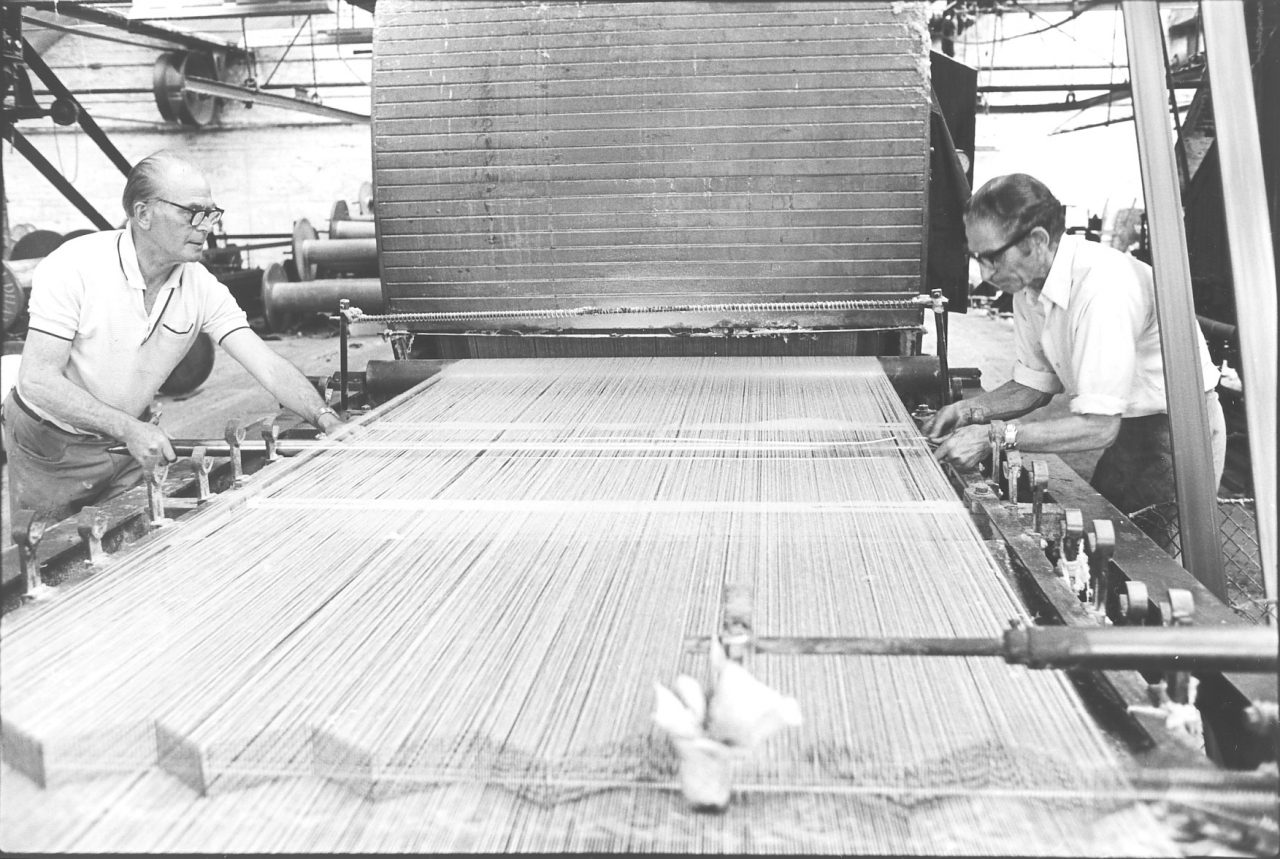

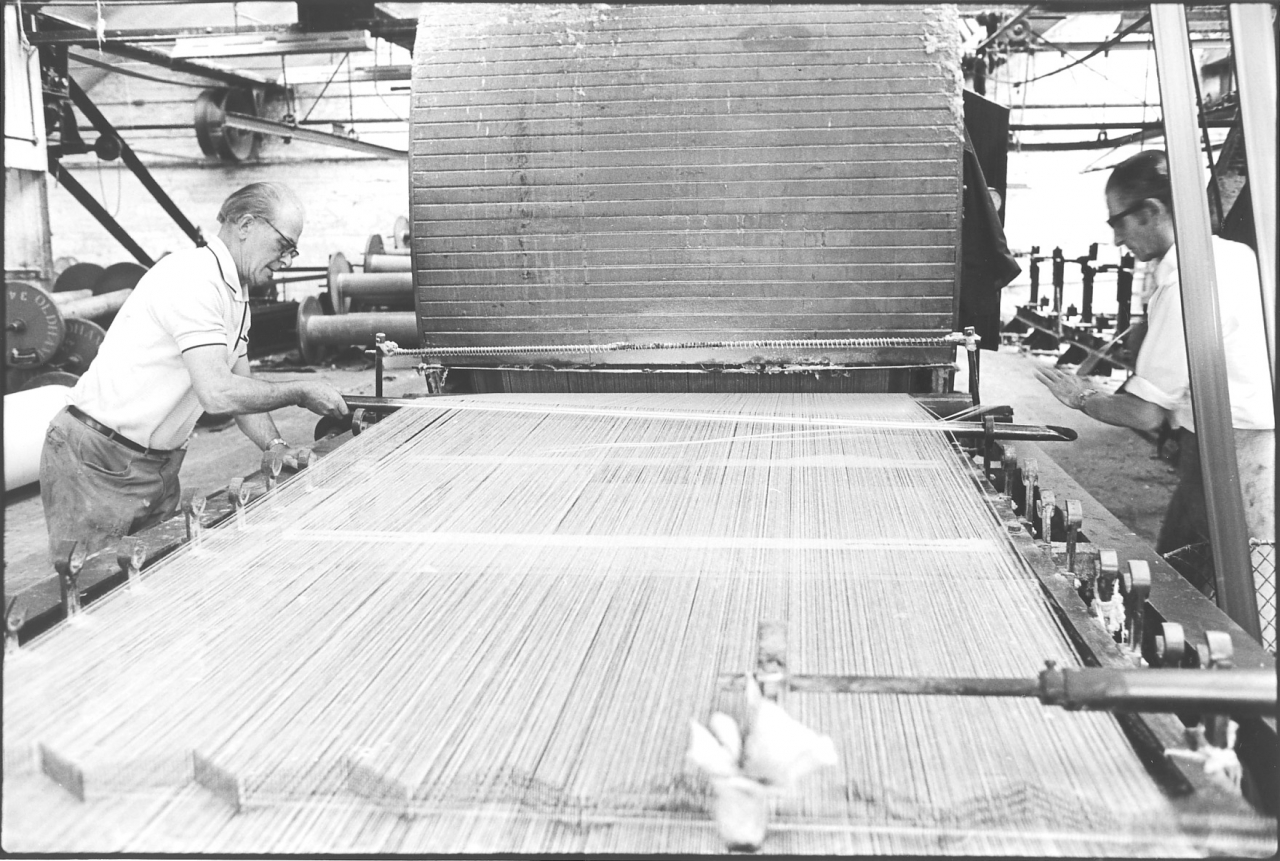

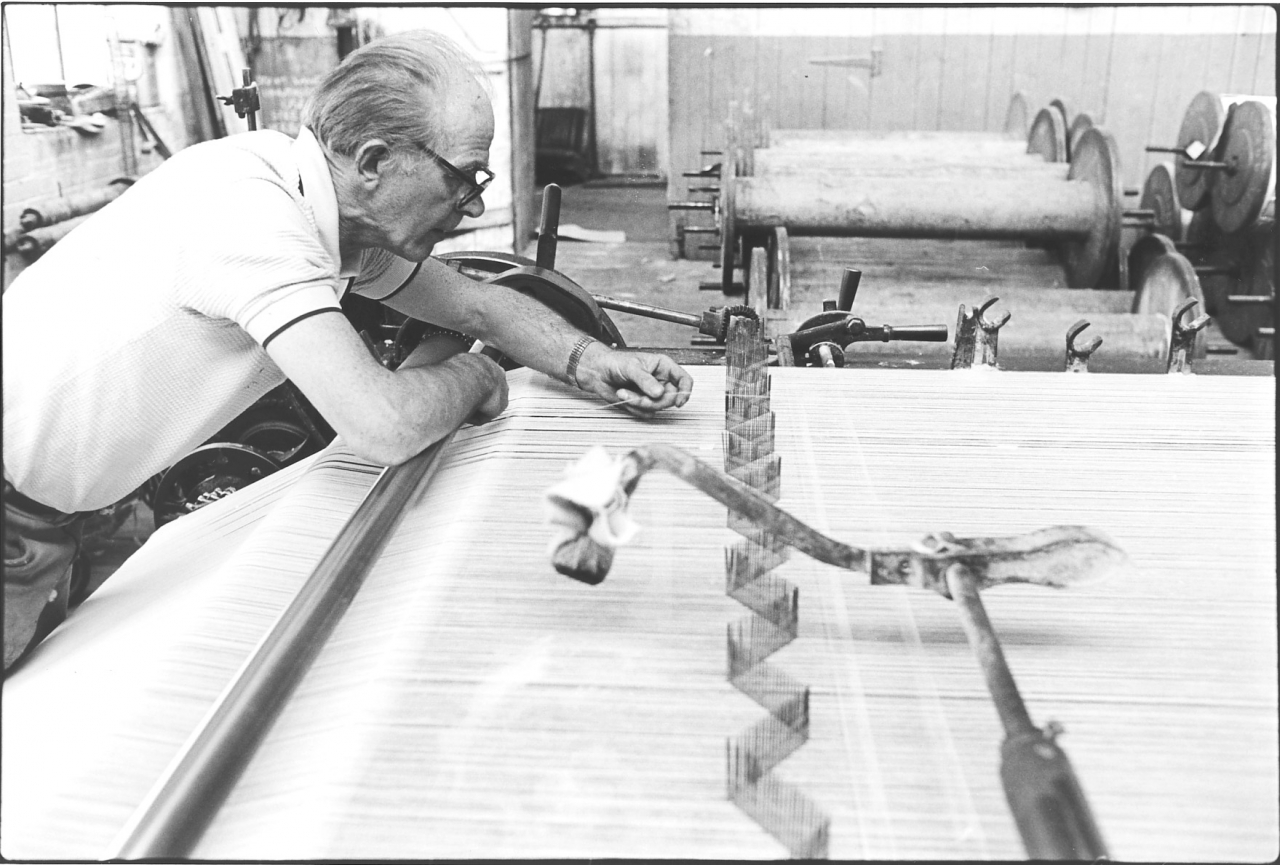

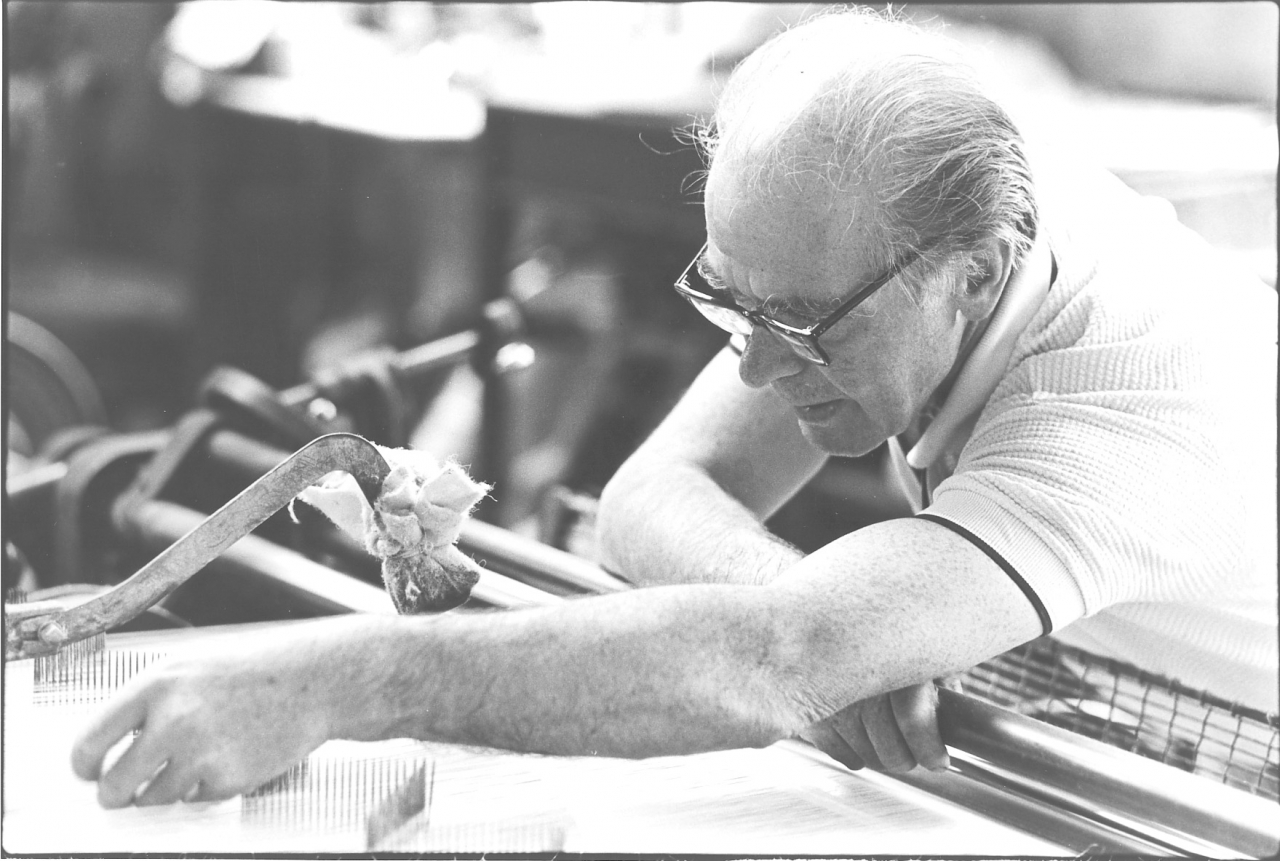

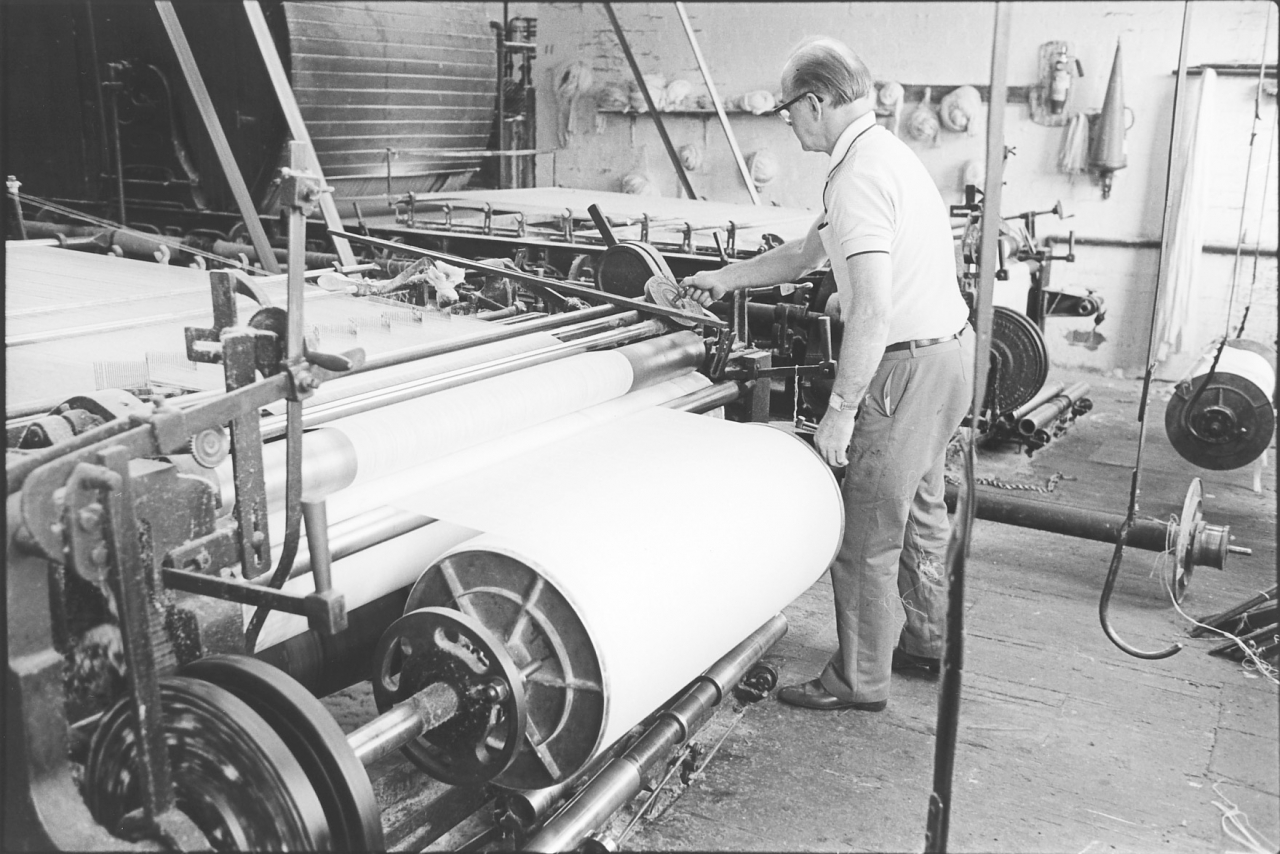

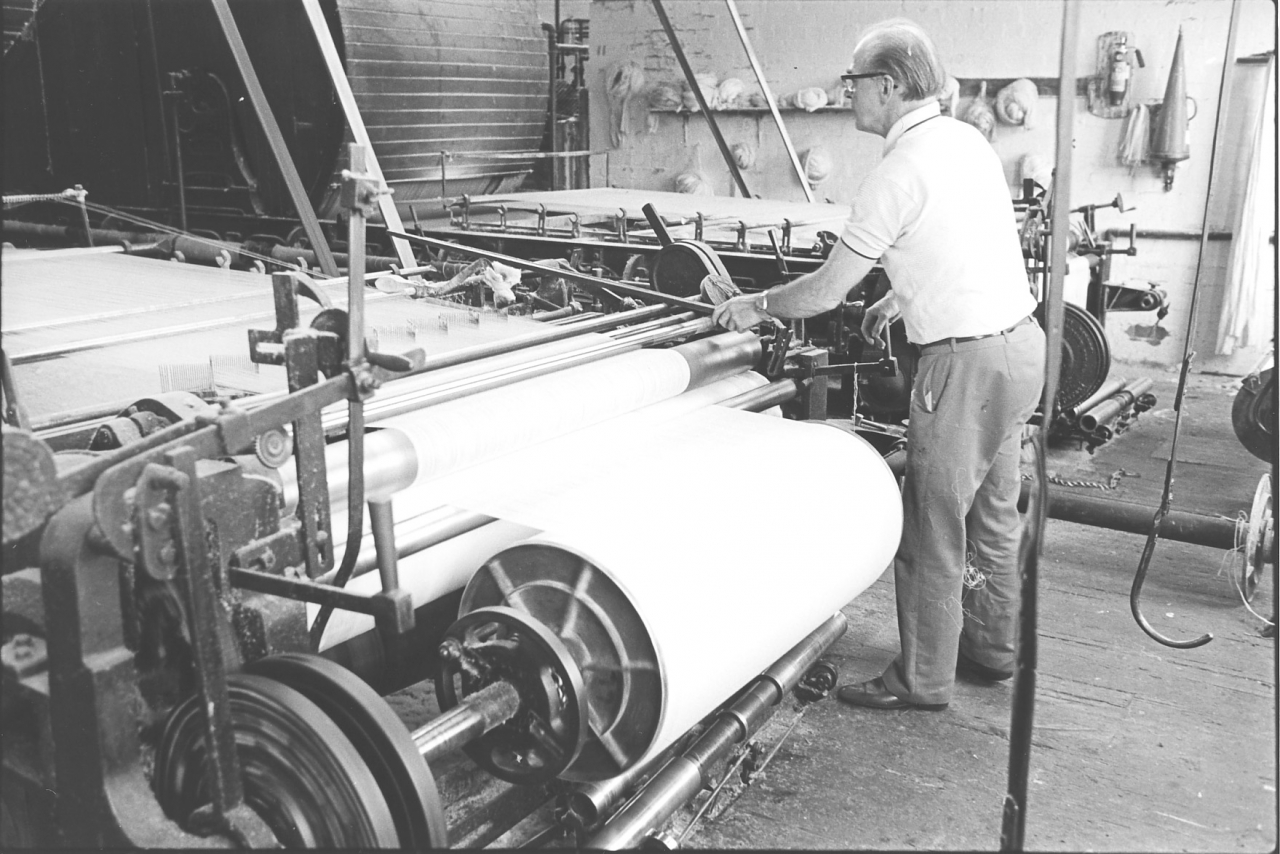

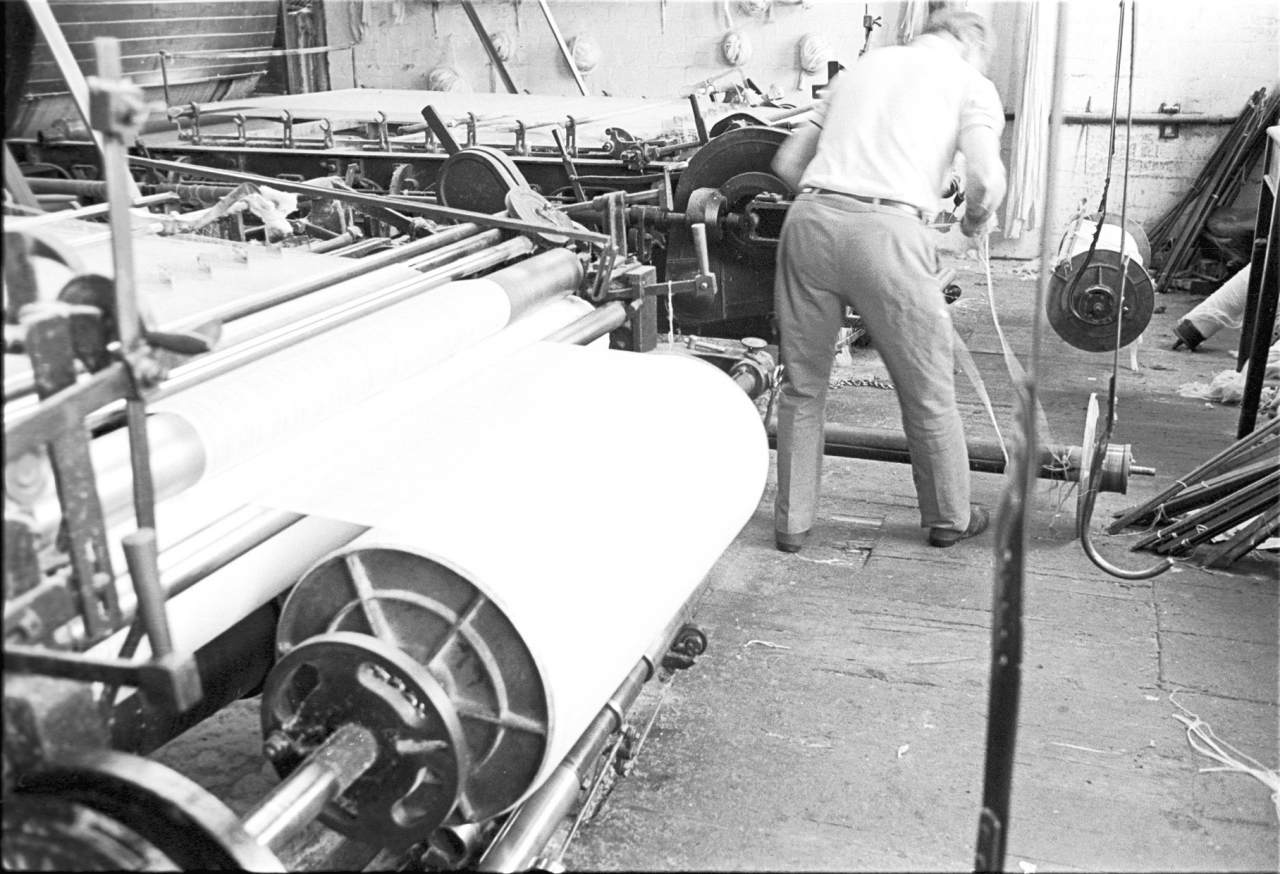

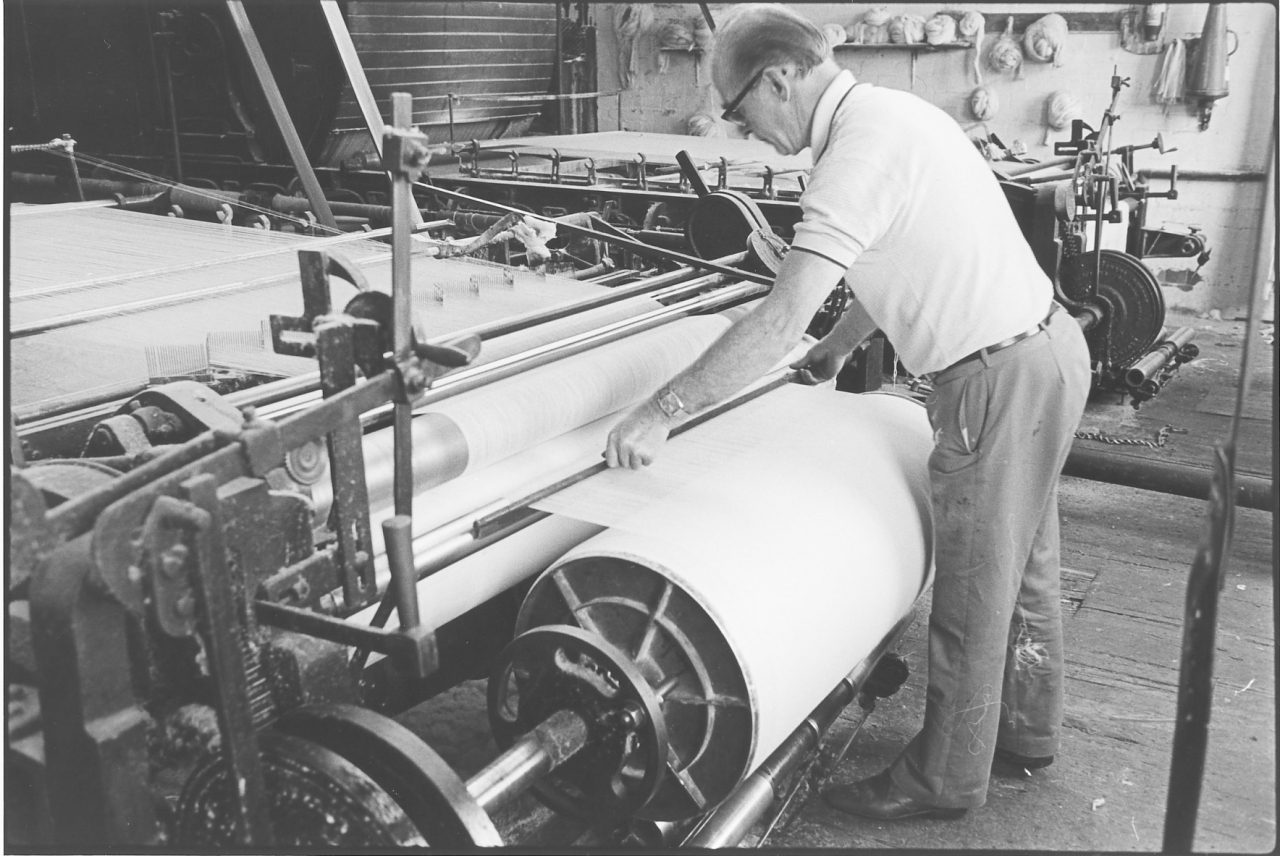

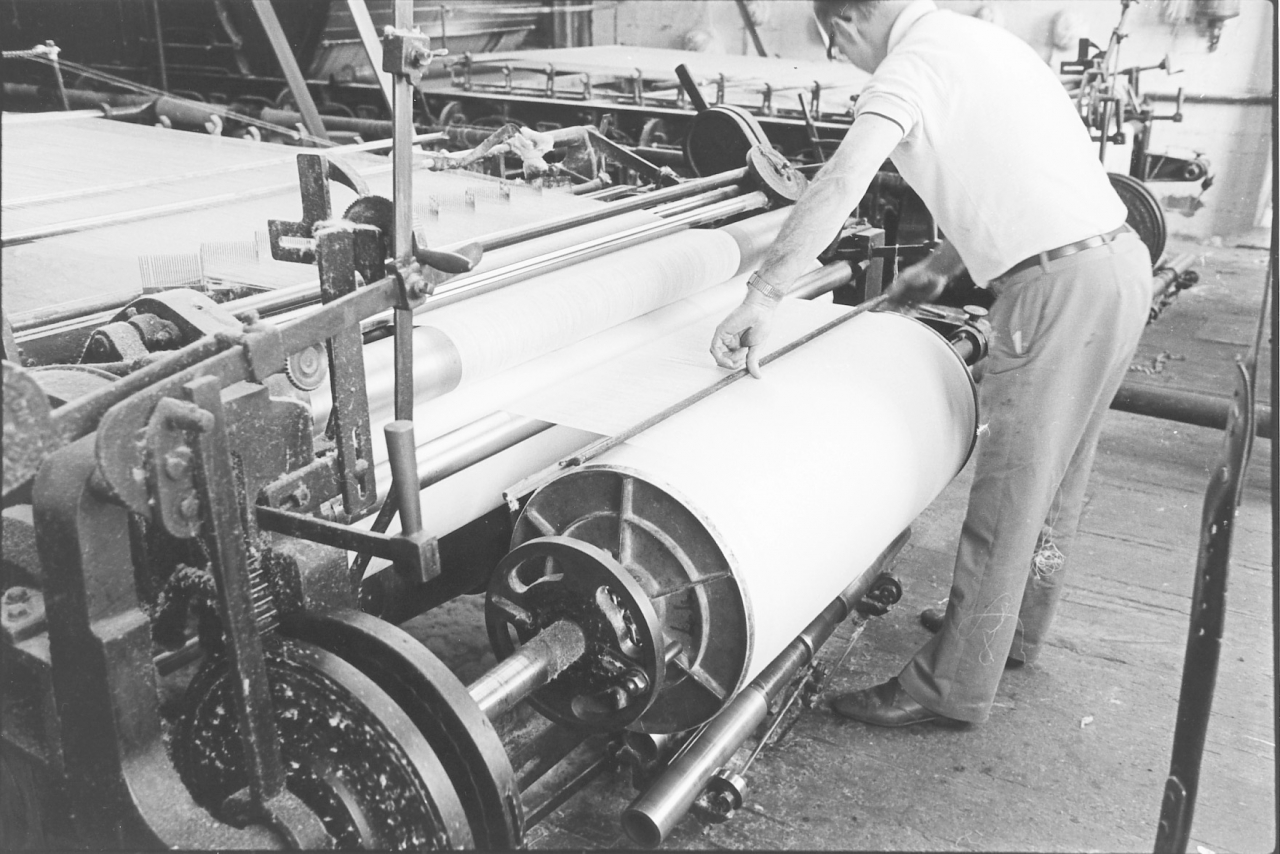

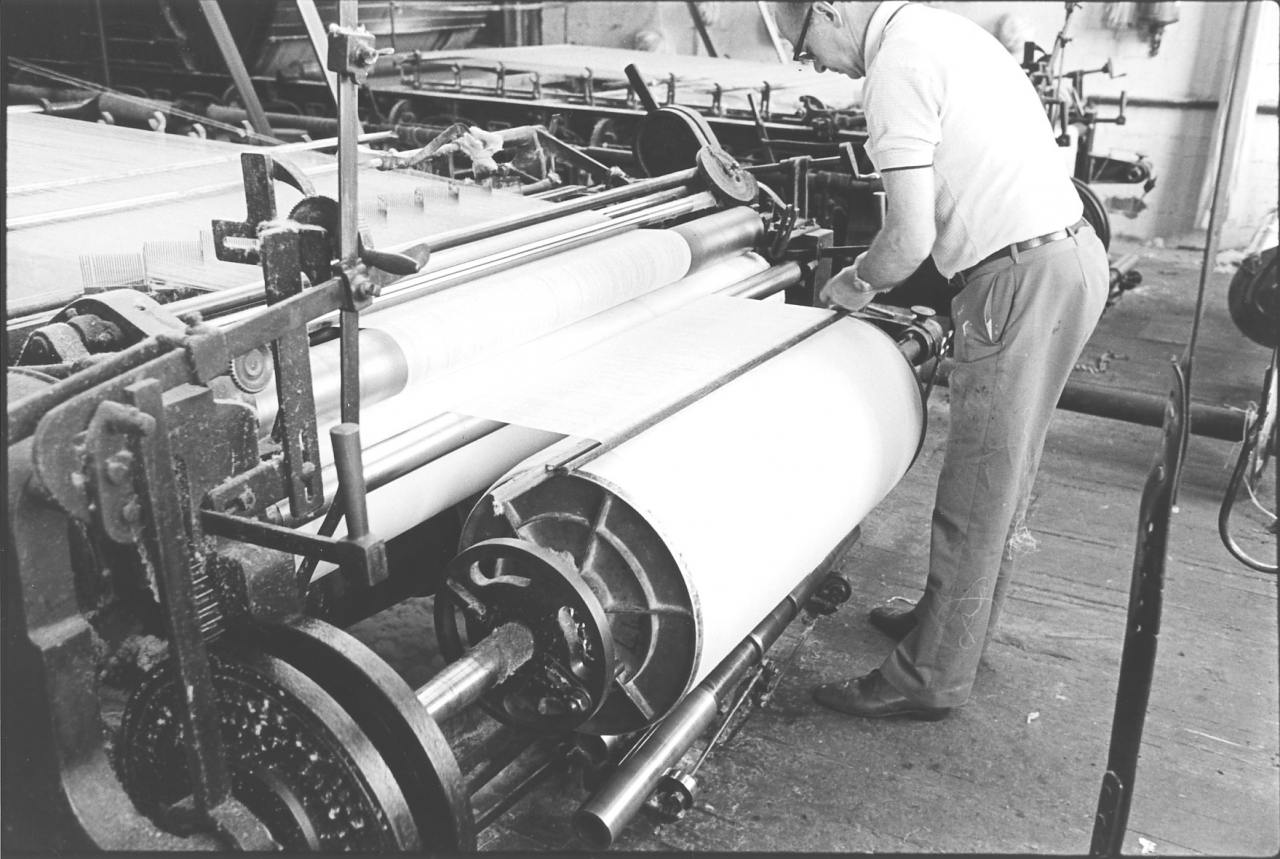

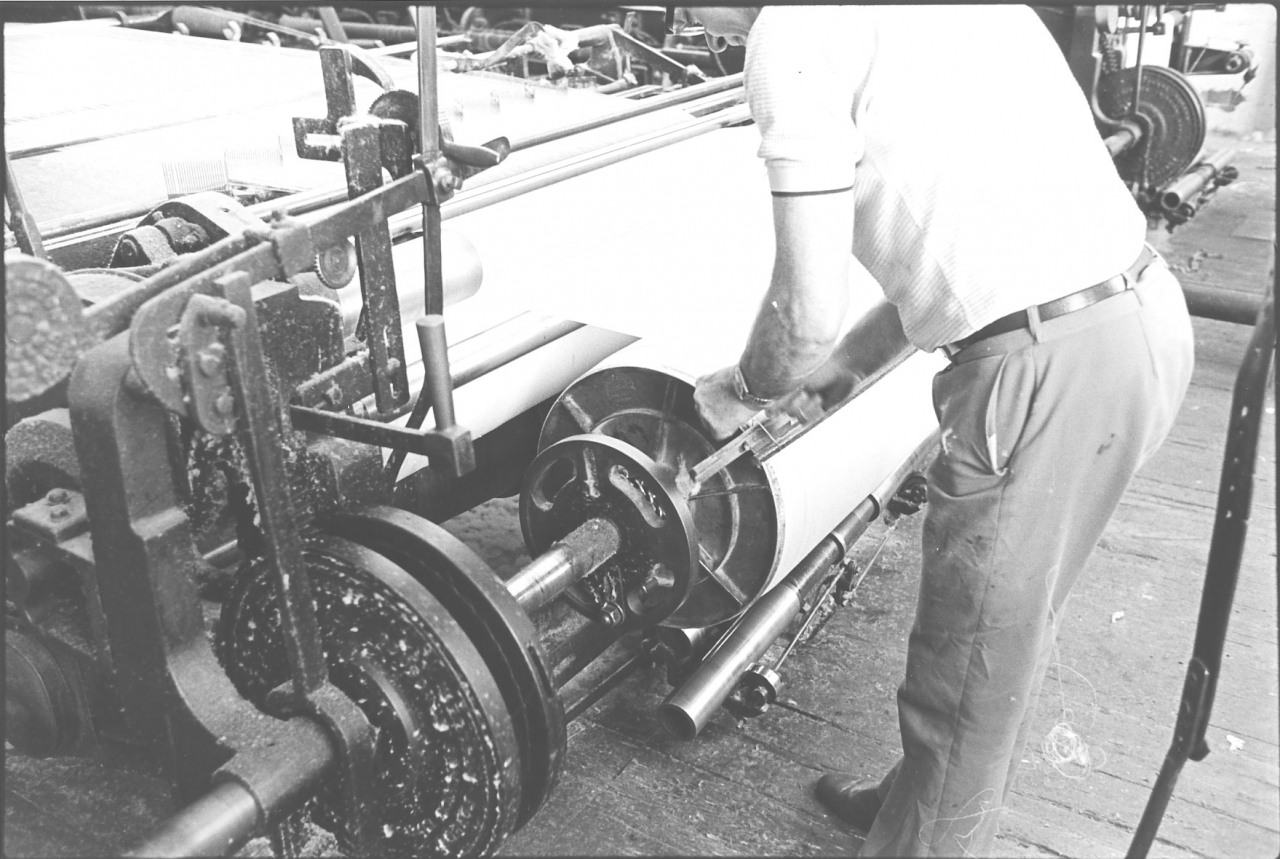

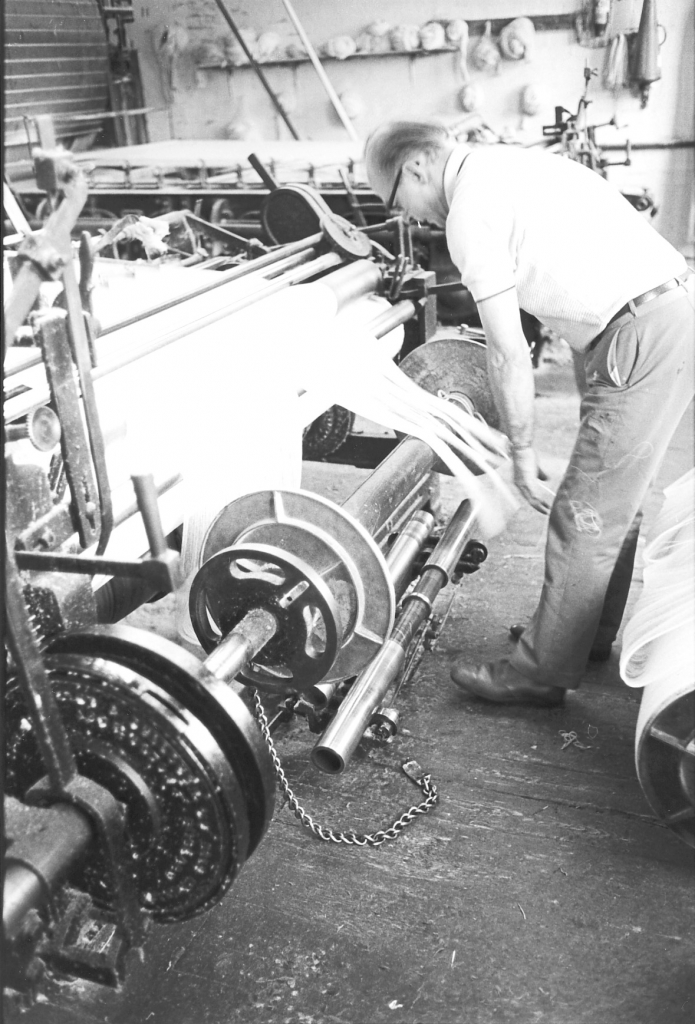

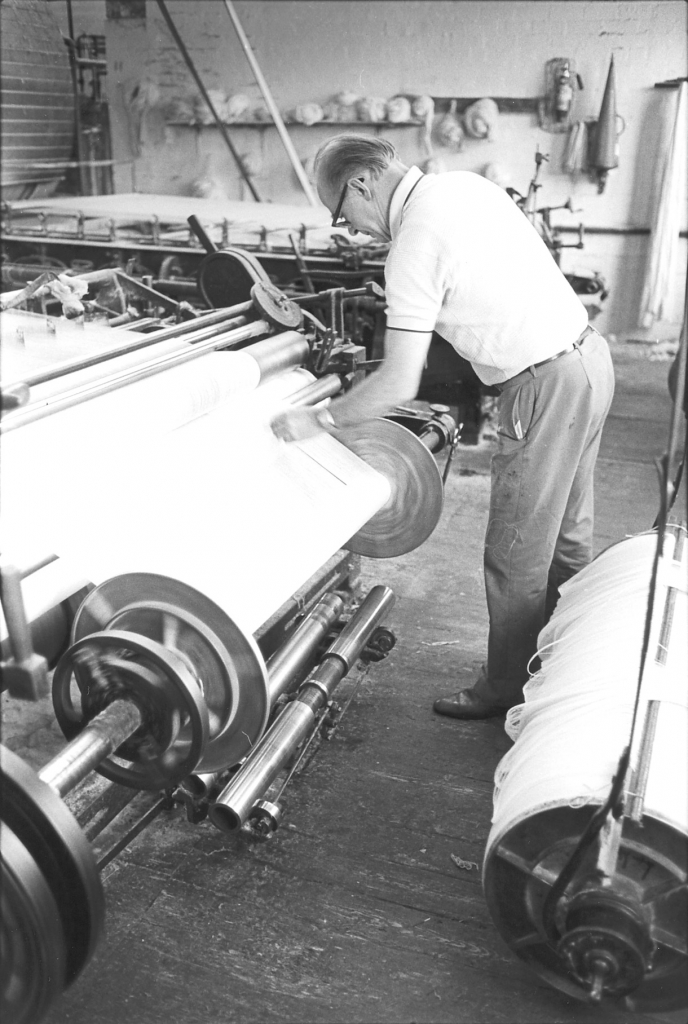

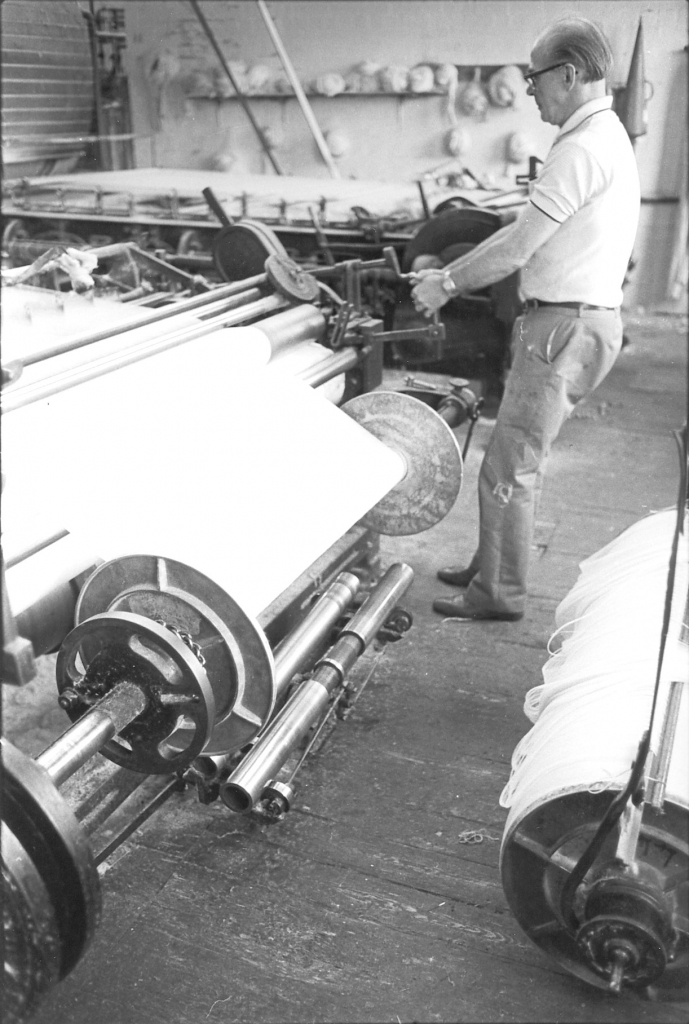

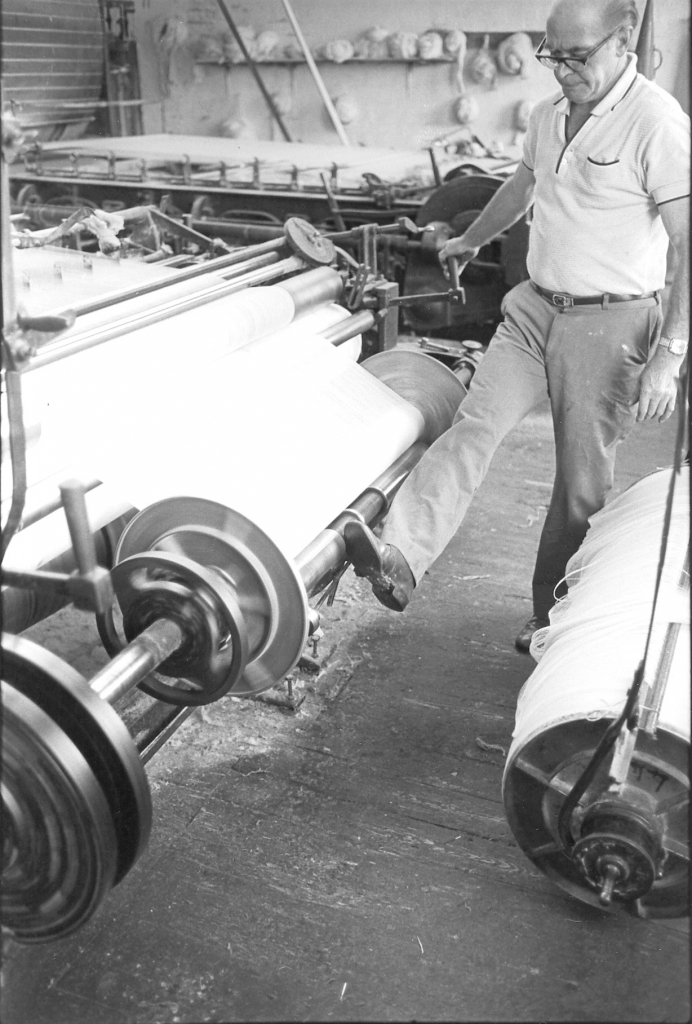

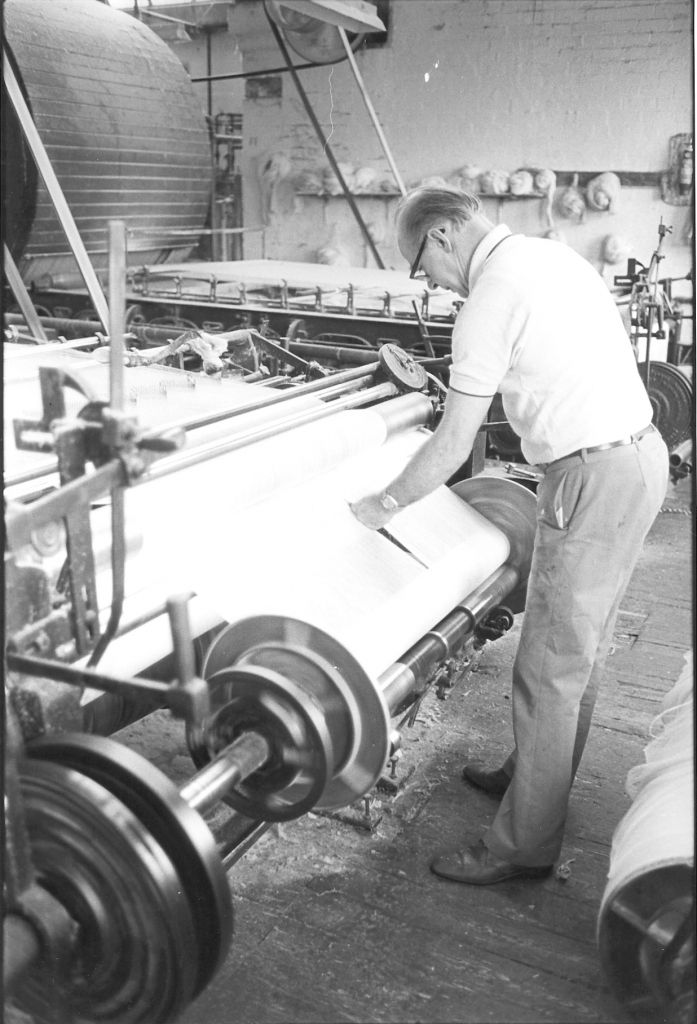

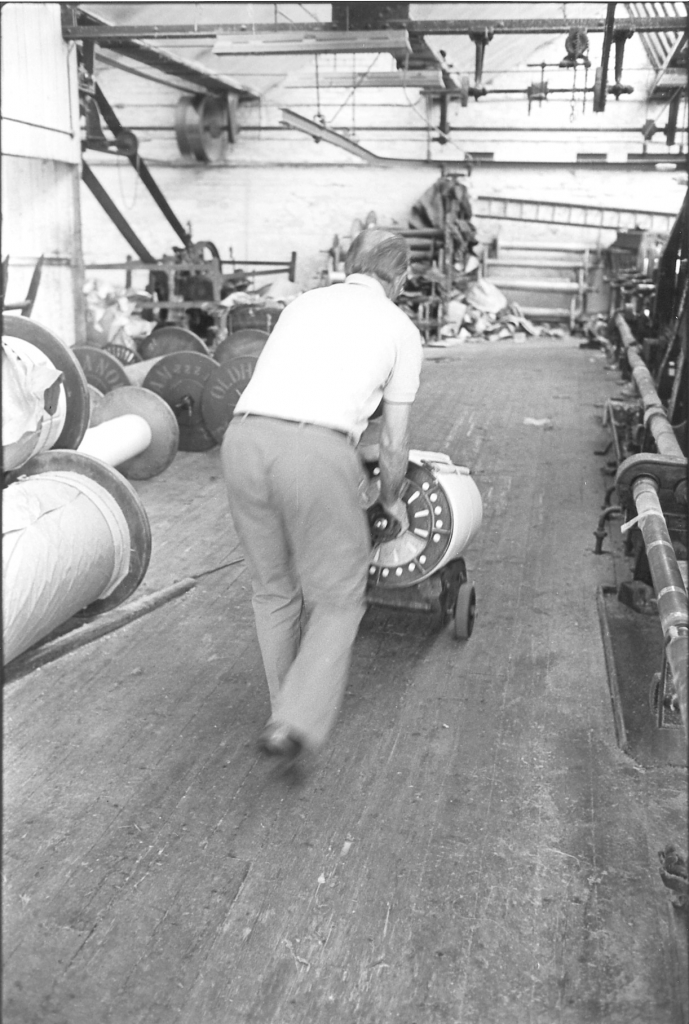

Horace in 1979.

Well, we’ll go straight on Horace. We’d just started talking about how you came to move from Rycrofts, how you came to finish at Rycrofts. So you go on in your own time.

R- Well it were an Earby man that were driving the engine at Rycrofts at Broughton Road, Bill Lancaster. Do you know him?

I’ve heard of him, I’ve heard Newton talk about him.

R- They called his father Bill Lancaster and he ran Big Mill Engine [Victoria Mill at Earby] And Bill were running Broughton Road engine and his father retired and young Bill got this engine here [Victoria Mill]. And I knew him fairly well because we’d travelled backwards and forwards on the train when I wasn’t cycling and staying to dinner, I used to go up into the engine house to pass me time on. And he’d said to me once or twice, “I can find you a job at Earby on the engine.” I said that were fairly handy, he said “I can find you a job there, maintenance and oiling and such.” I says “Well, I can’t get away.” I were stuck. Well, that regulation were squashed from the first of January 1945. Everybody were free. So I gave me notice in the week before and started on the engine here on the 1st of January. Never forget that day. And Johnson’s had the main of the shed here, there’s only the engine belonged to the Mill Company, [Johnson’s were in Victoria Mill as room and power tenants at the time. The mill was owned by The Mill Company.] there were one or two small firms and I did about two year on the engine.

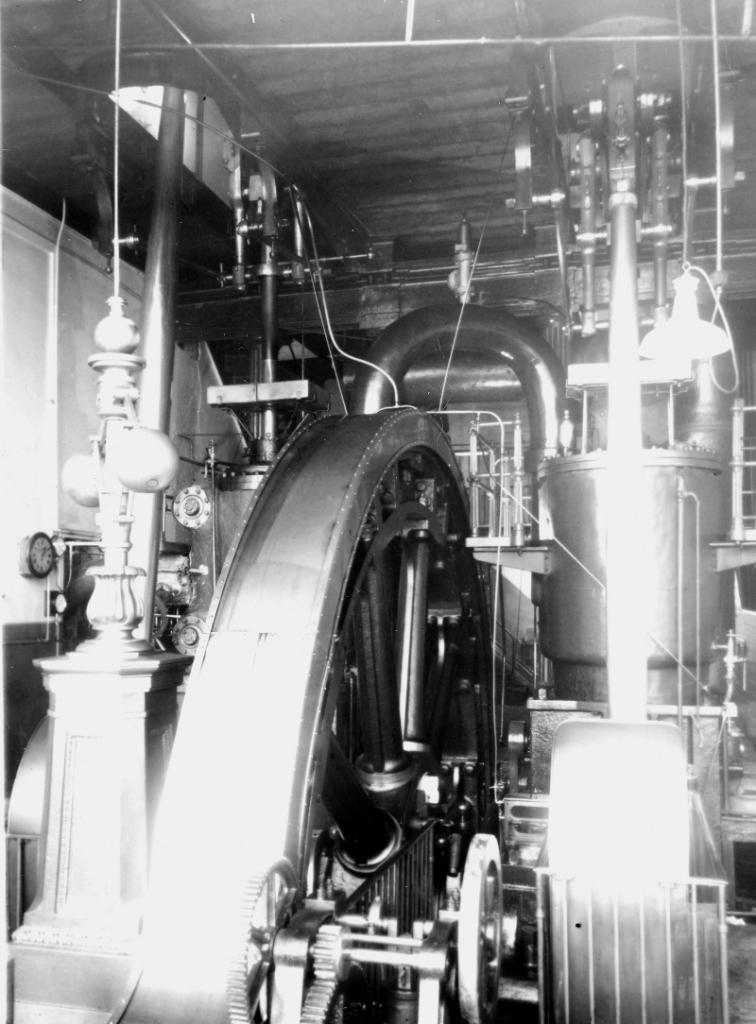

The Victoria Mill engine at Earby. A very large and economical beam engine.

What were you doing on the engine?

(5 min)

R- Everything, oiled it and cleaned it, and certain times in winter time you were stoking the boilers. There were another man besides me and the boiler fireman and in winter time you took it in turns, they were all night steaming trying to keep the place warm. [The Factory Acts stipulate that a certain minimum temperature has to be attained by starting time. In my days it was 55 degrees Fahrenheit and badly insulated buildings like the weaving sheds needed steam heat most of the night to warm them to the minimum standard. In those days there were no automatic controls or firing on the boilers and so the firebeaters had to be there.]And if the boiler man was on all night one of us had to go on the boiler during the day. And I’d been working there about two years, and the manager at Johnson’s came to me, he says “Oh, you worked in a cotton mill and you were about tapes weren’t you?” I said “Aye. I spent a lot of time as a lad in the tape room, you’d go labouring there.” He says “Well, we want someone to learn taping. What do you think about it?” I says “Yes, it’ll be all right.” And he said “You’ll not be starting taping just now but we want you to go to the night school at Burnley and you’ll go on a dry tape here.” And Johnsons were bringing in dry taping, not sizing the warps. It was such light stuff a lot of them would [weave without size] If the yarn were strong enough a lot of them’d weave without size on. And I went on to

(150)

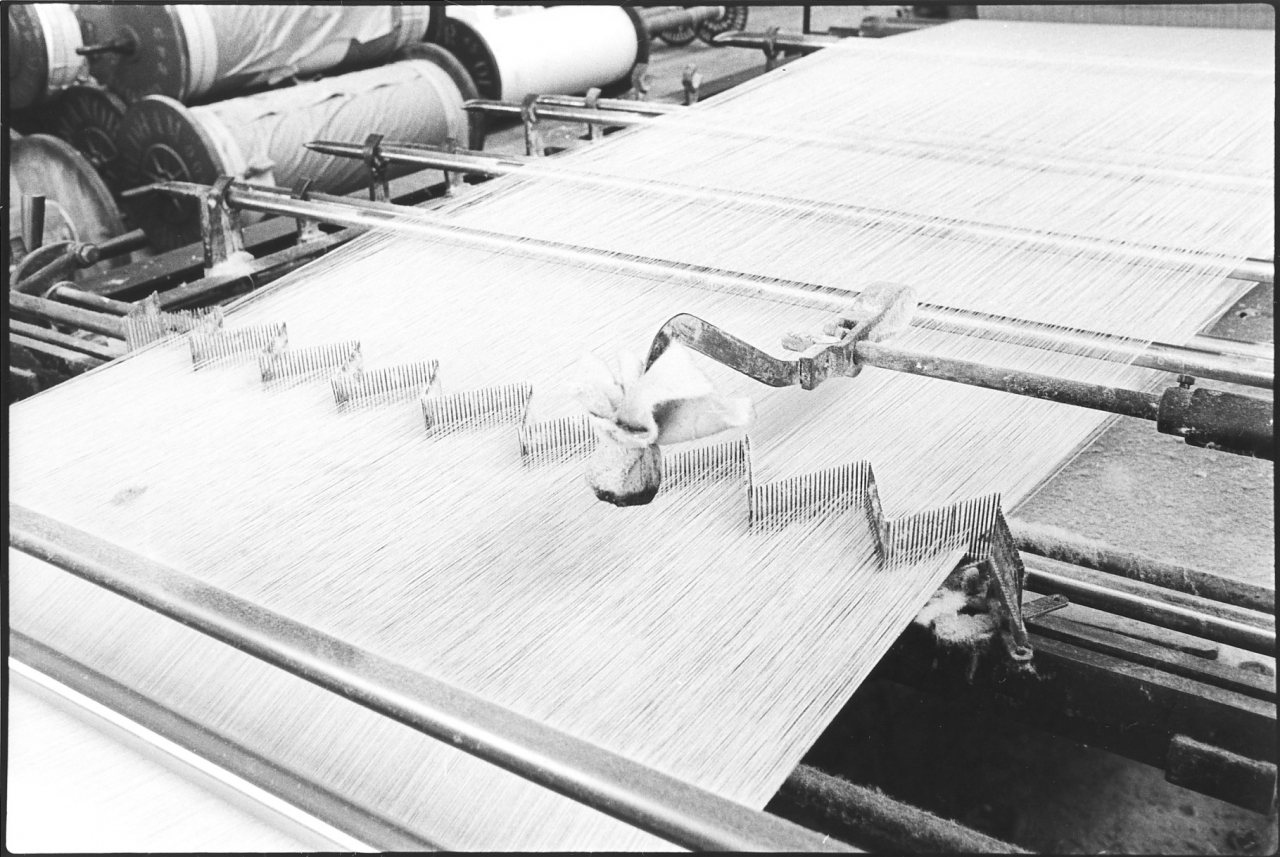

this dry tape, it were only in its infancy. There were same as a beaming frame but high speed and they were all pinned, and they were trying different ways of pinning you see, electrically. Not just the old pin that dropped. [Horace is talking about a warp stop motion. From its inception, this was a mechanical system where fork shaped pins rode on each strand of the warp and if one broke these dropped and mechanically stopped the loom or other machine. Johnsons were trying to innovate and bring in an electronic system for doing the same thing which would be more reliable and simpler to set up.] And there were a taper left, Maurice Lomax, you know Maurice Lomax, he’s a Barlick chap. And I went into t’tape room on to his tape, and that were how I were taping at Johnson’s.

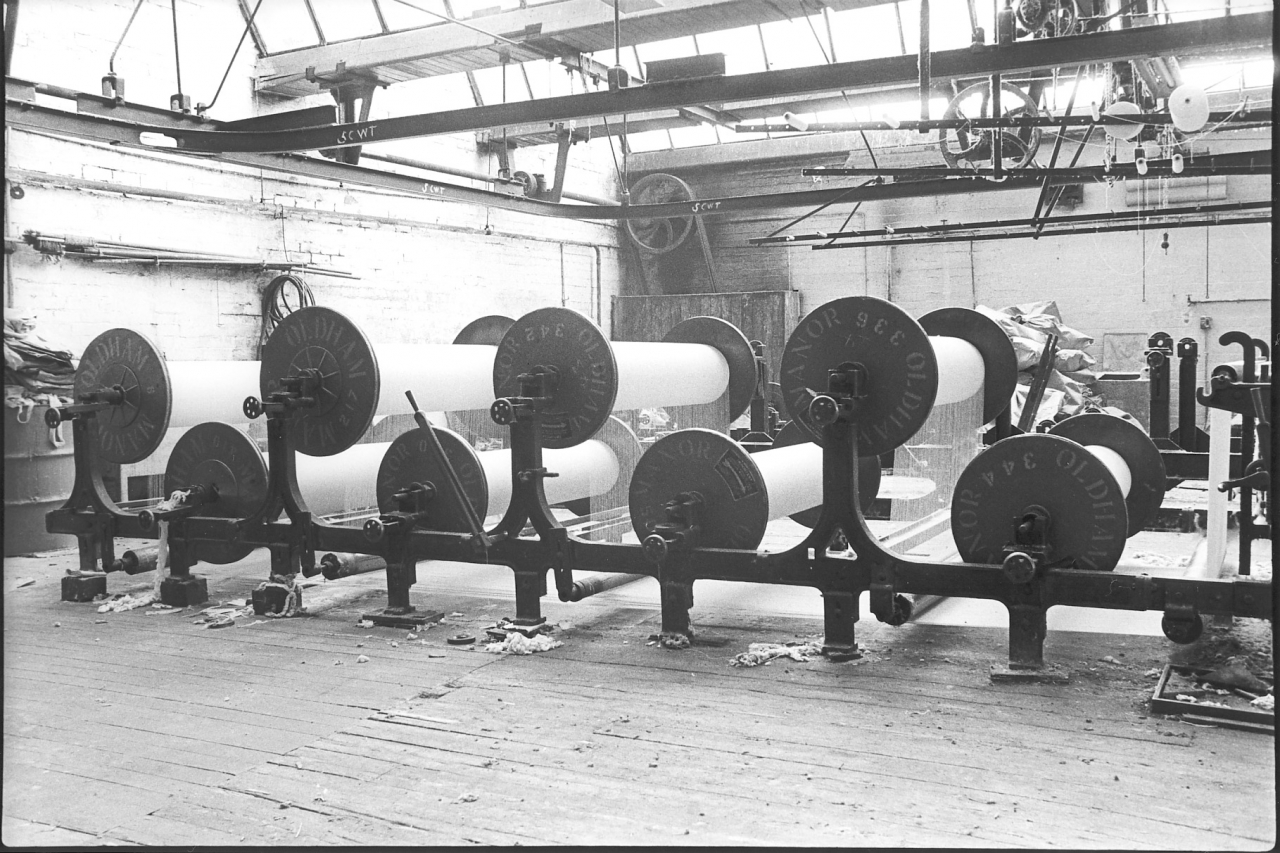

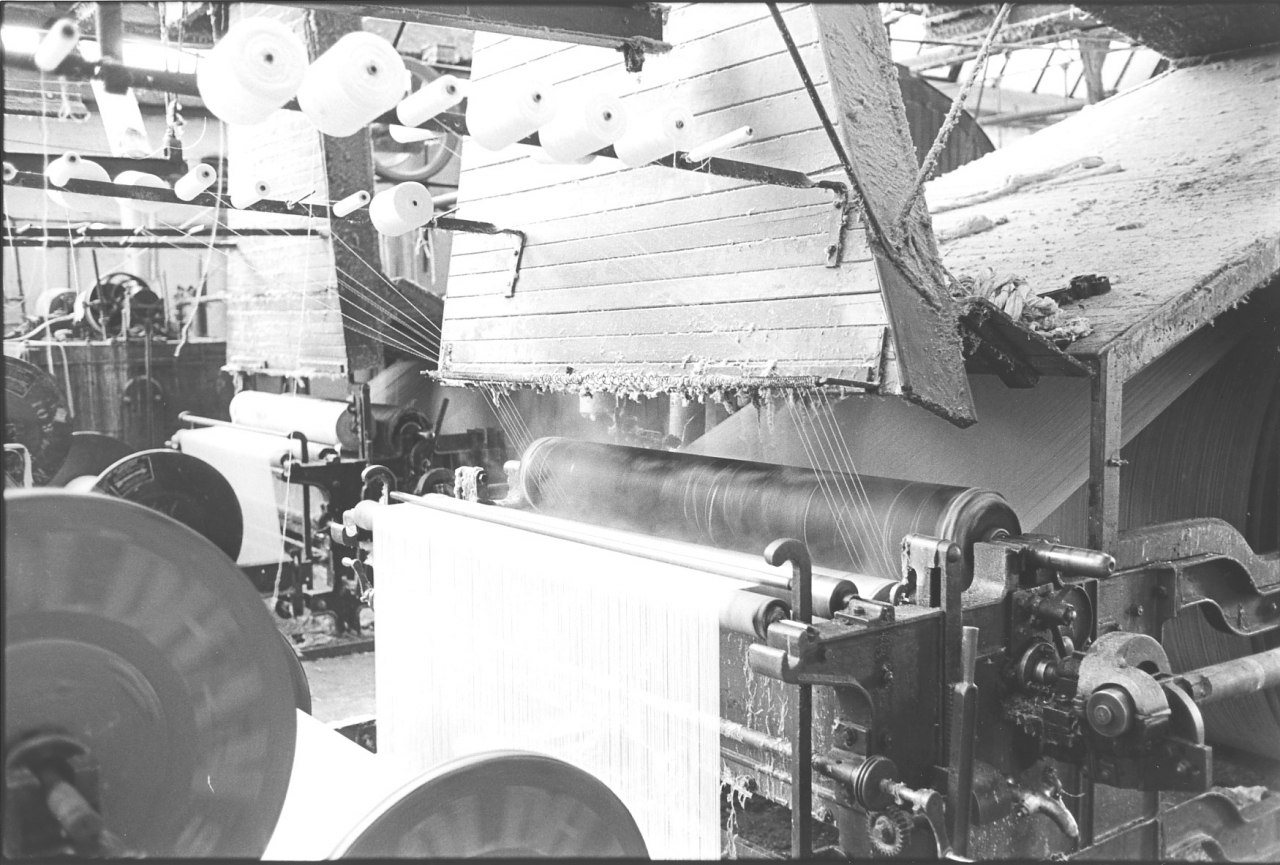

What sort of a tape was it?

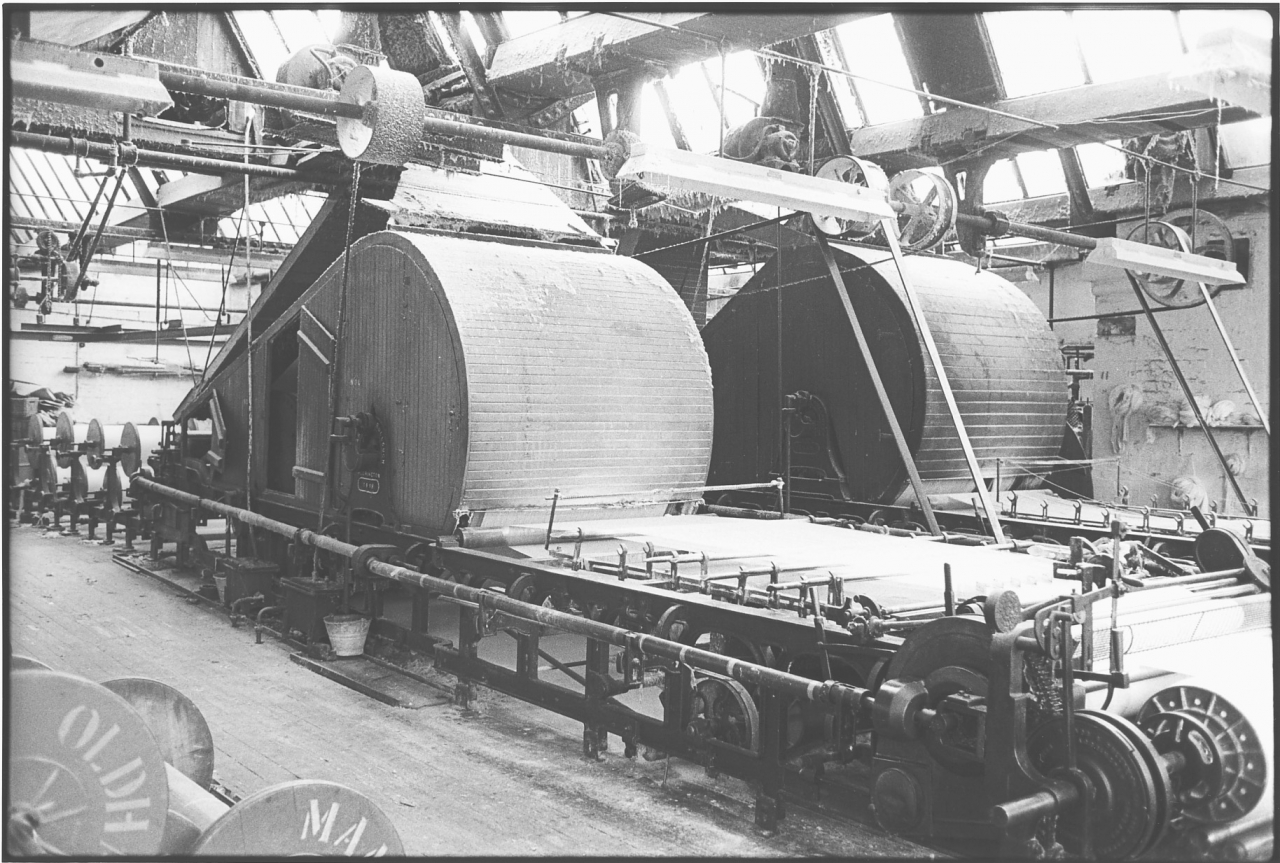

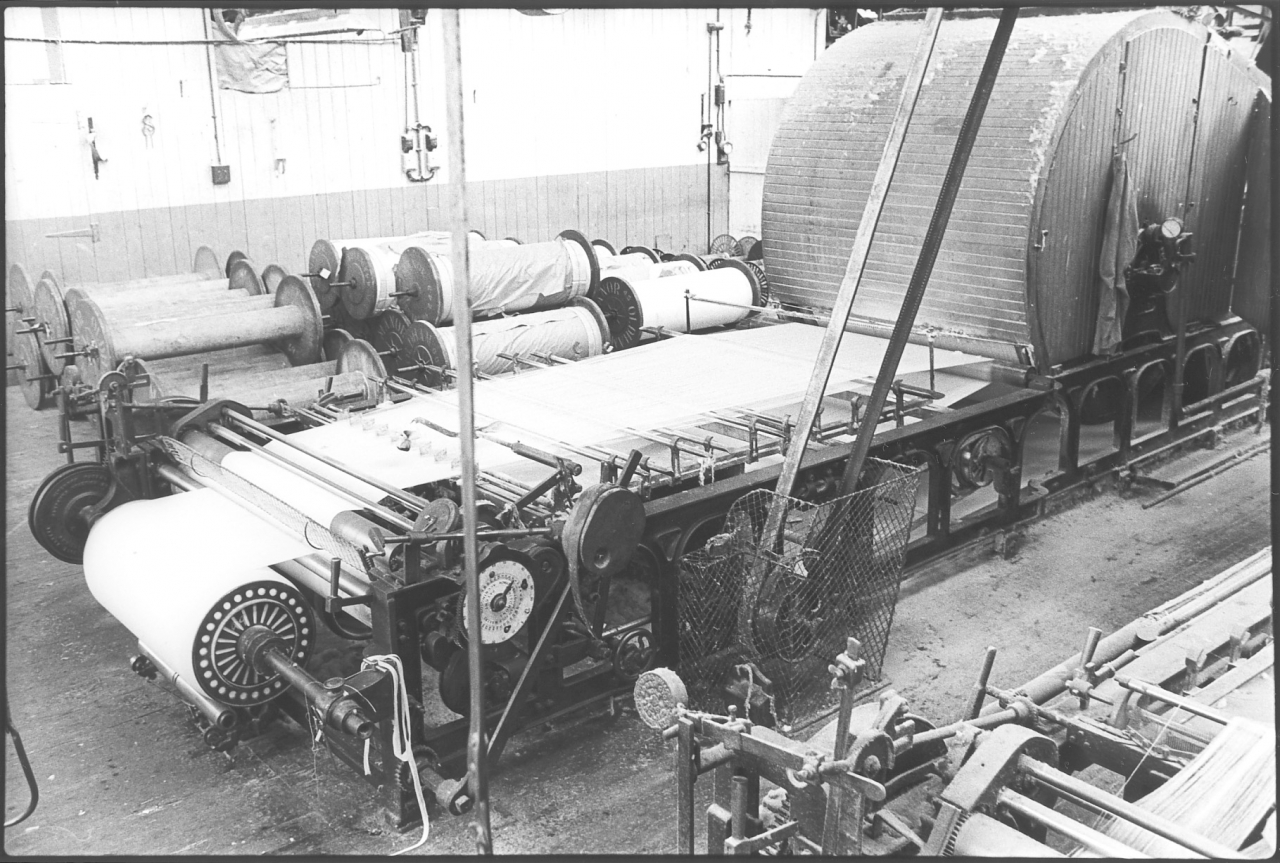

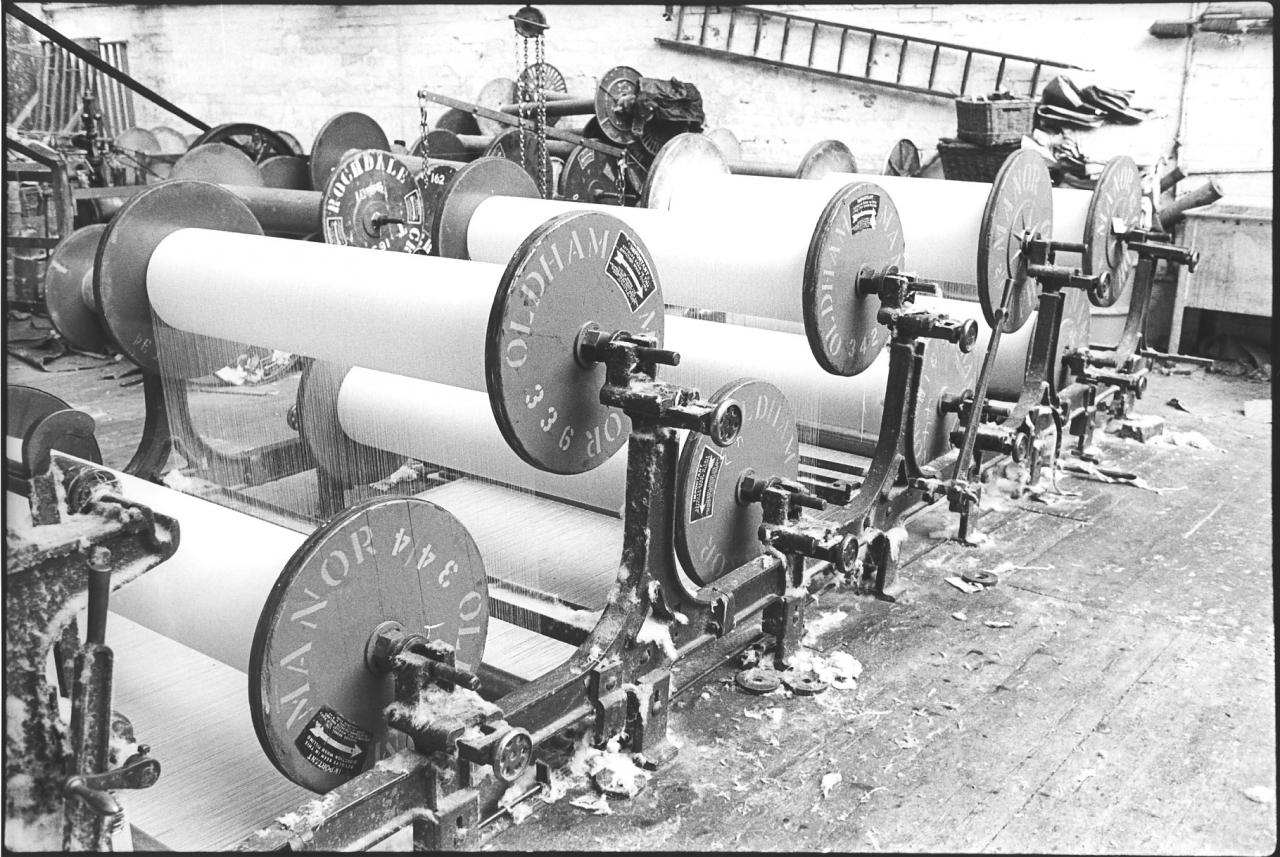

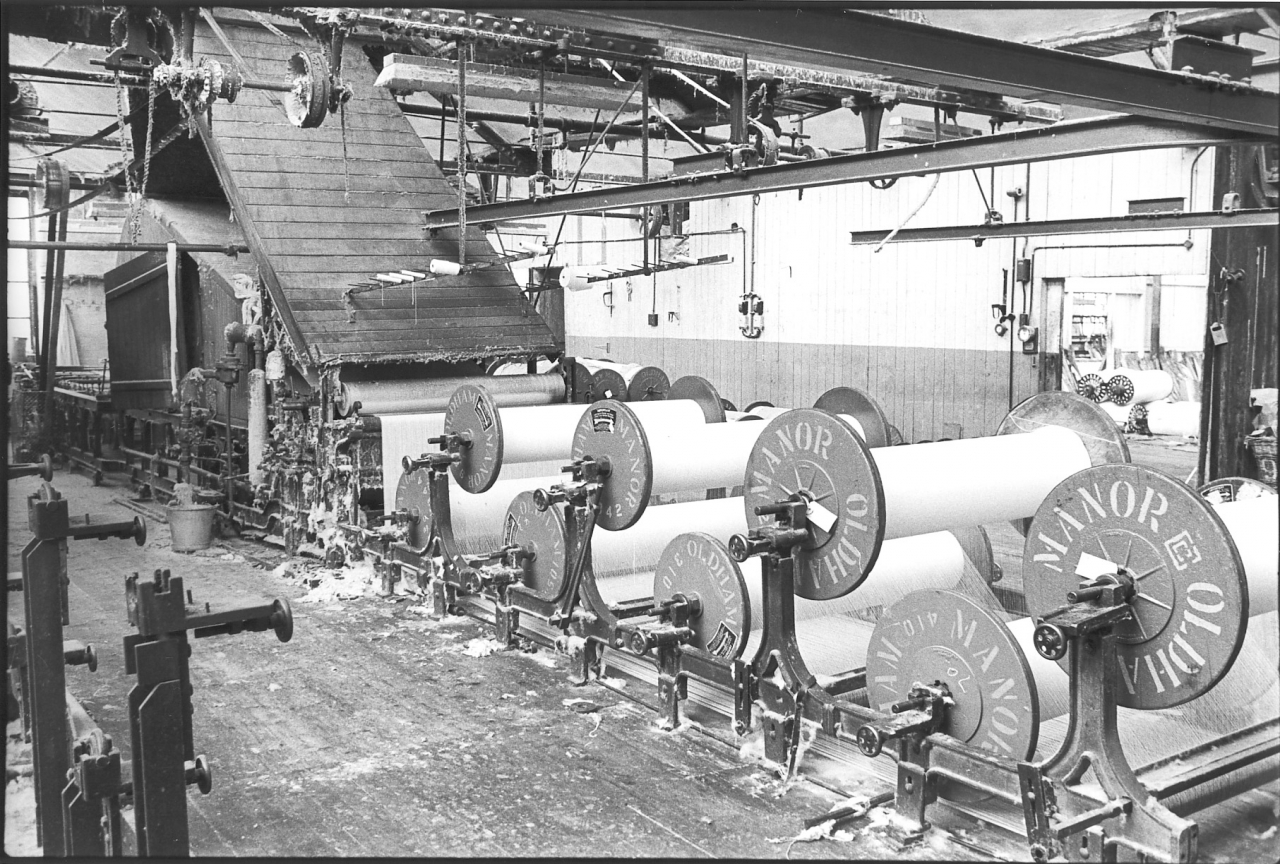

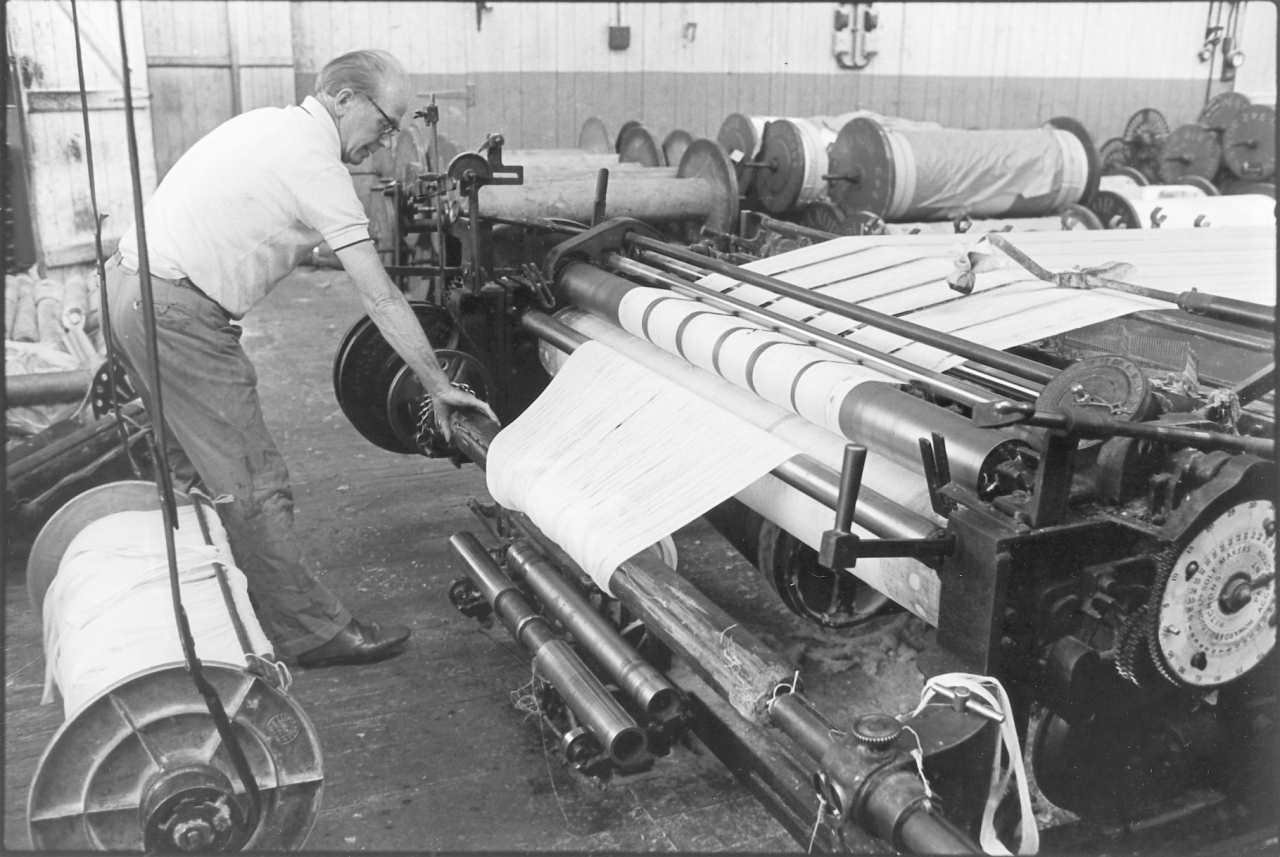

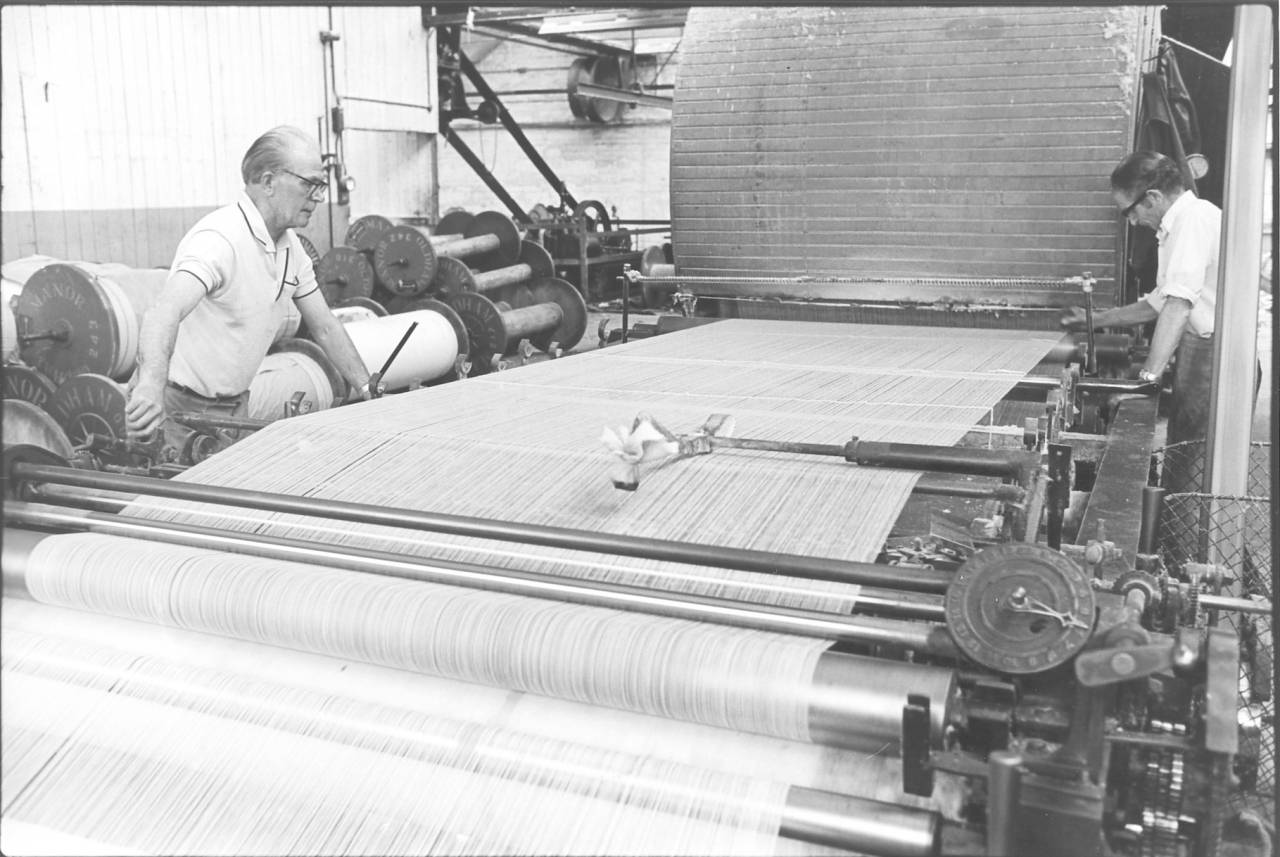

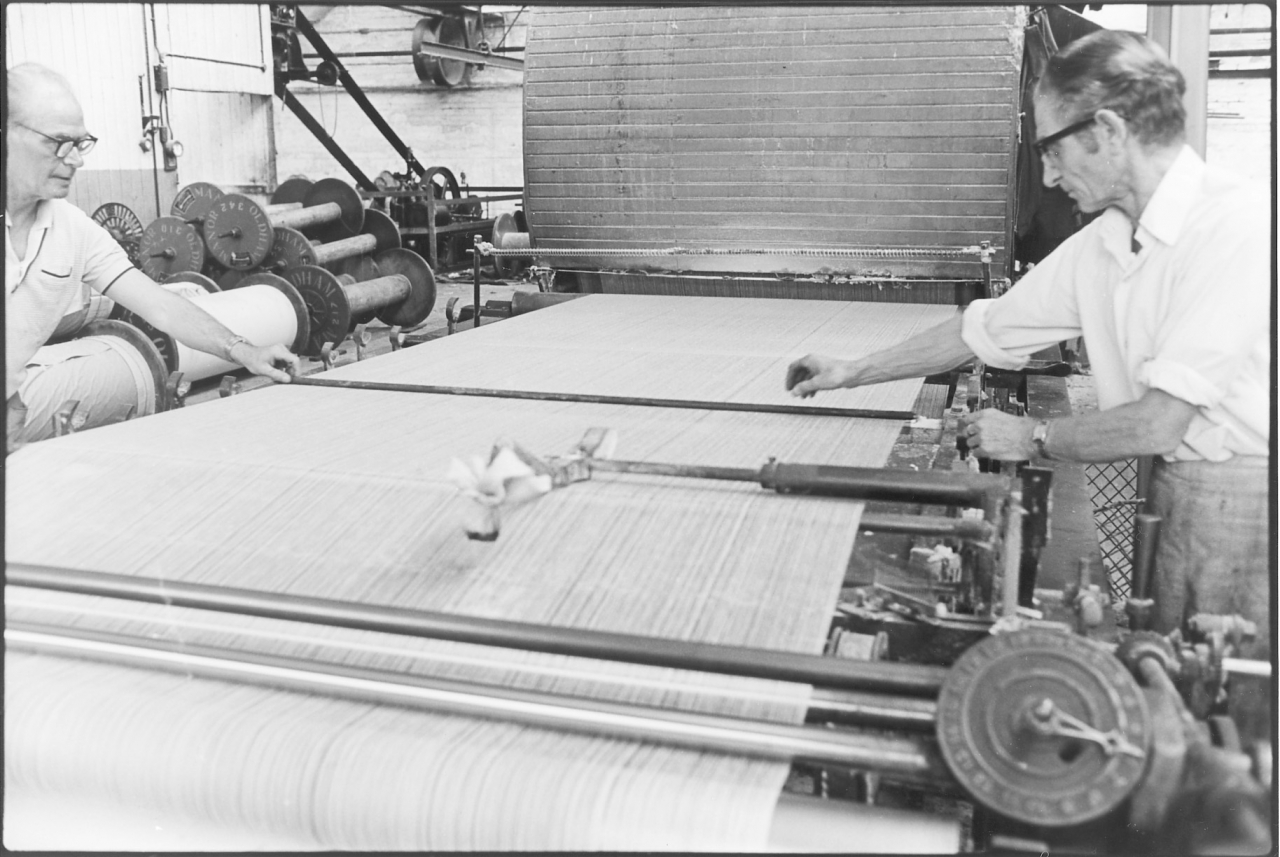

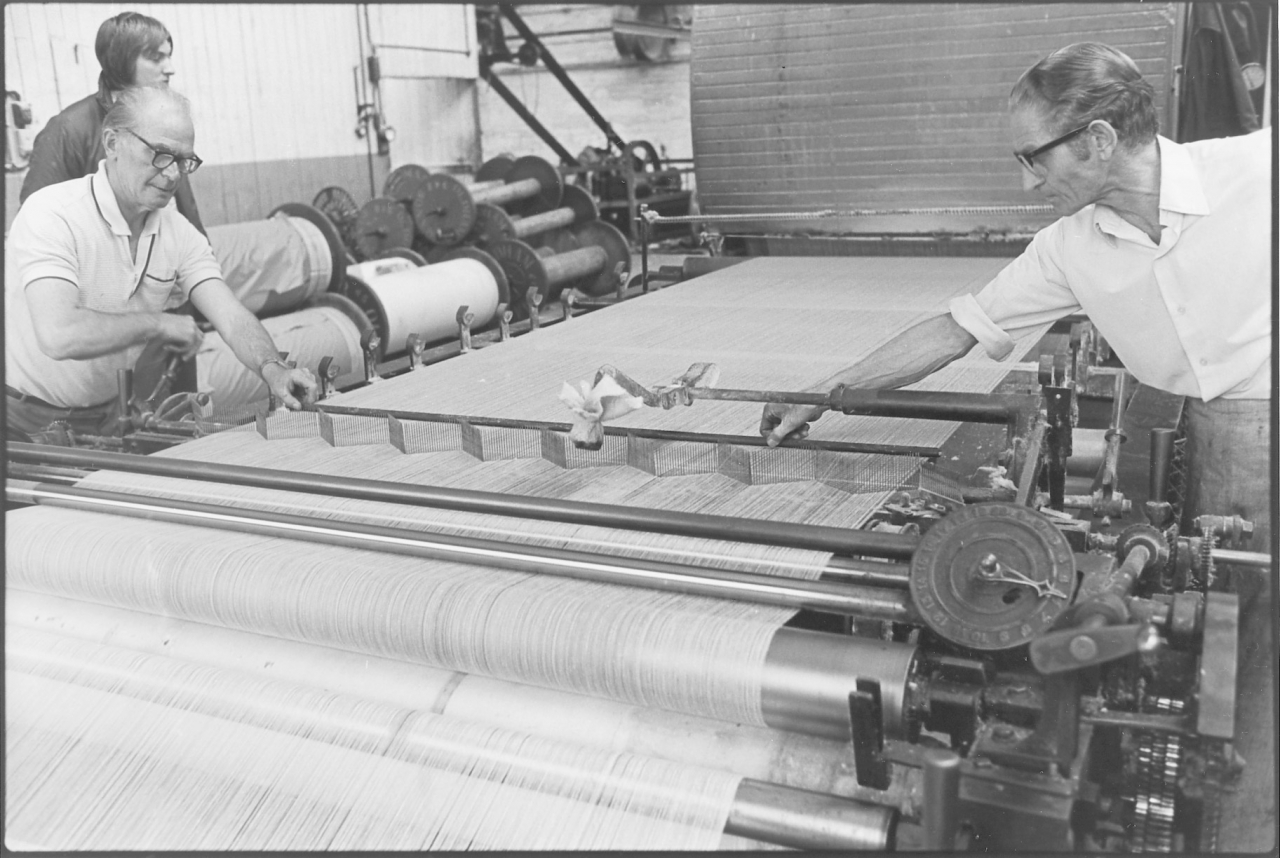

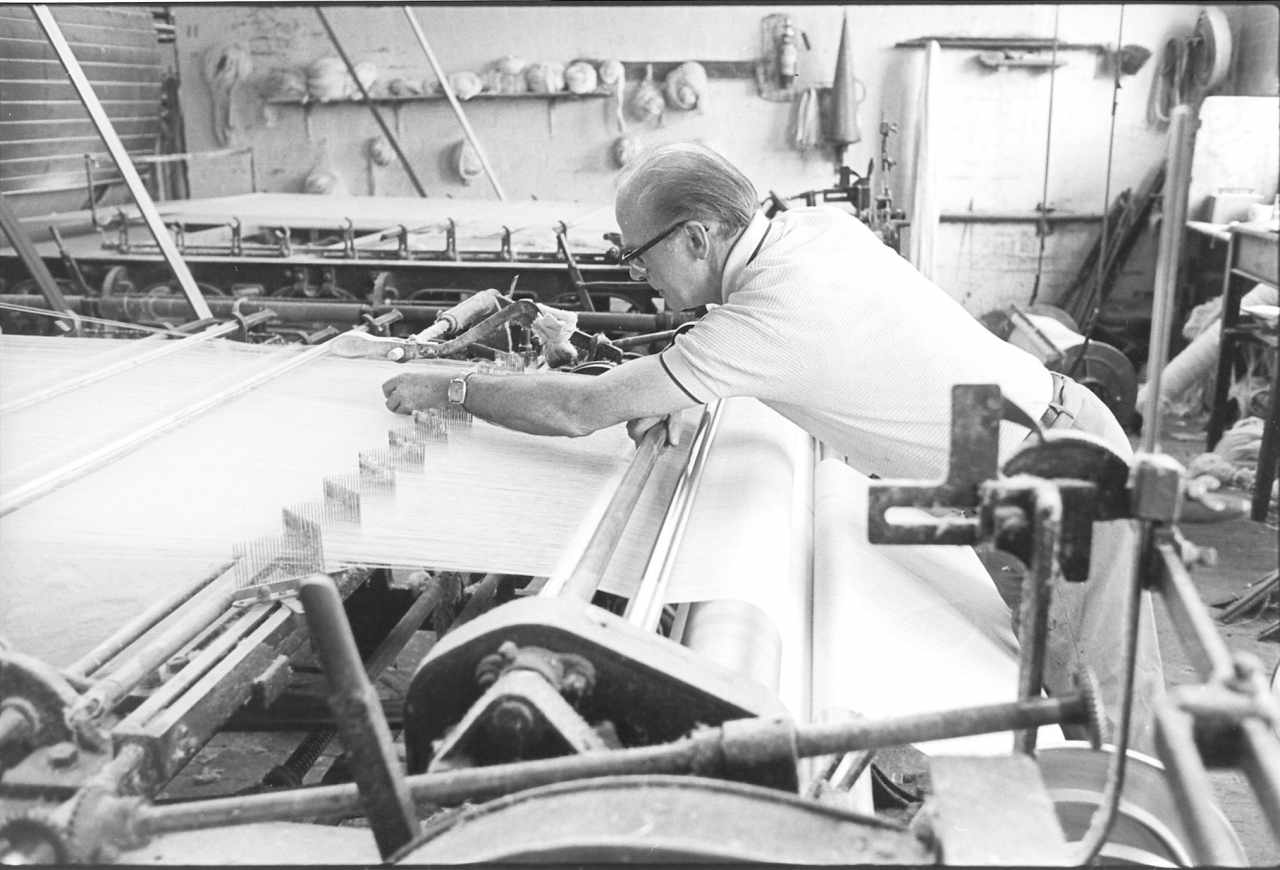

R- A double headstock. They’d five tapes there and there were three of them that always ran light stuff you see. They were only sort of running light warps through water, and there were this, what they called the big tape, ran all the heavy stuff. And I went on to that, and a double headstock..

Now what do you mean by a double headstock?

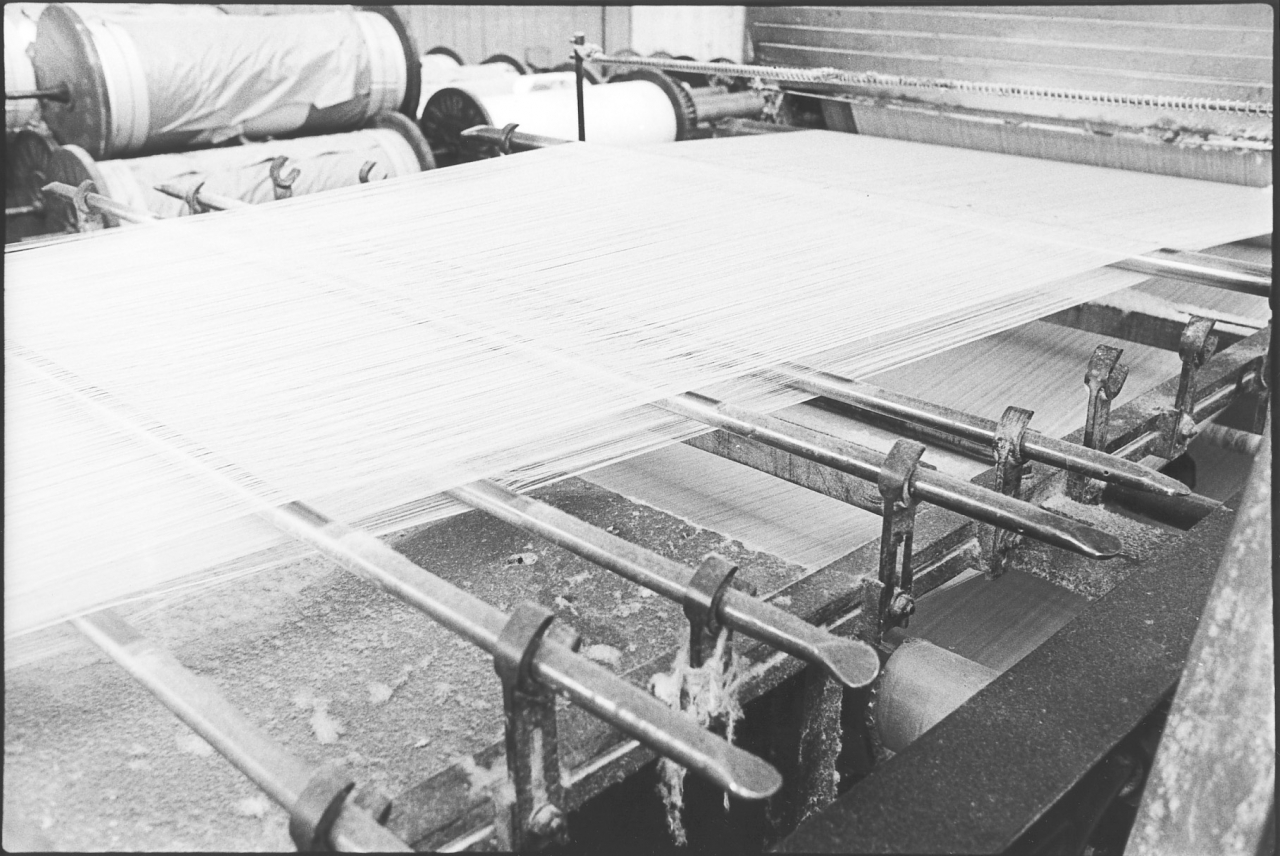

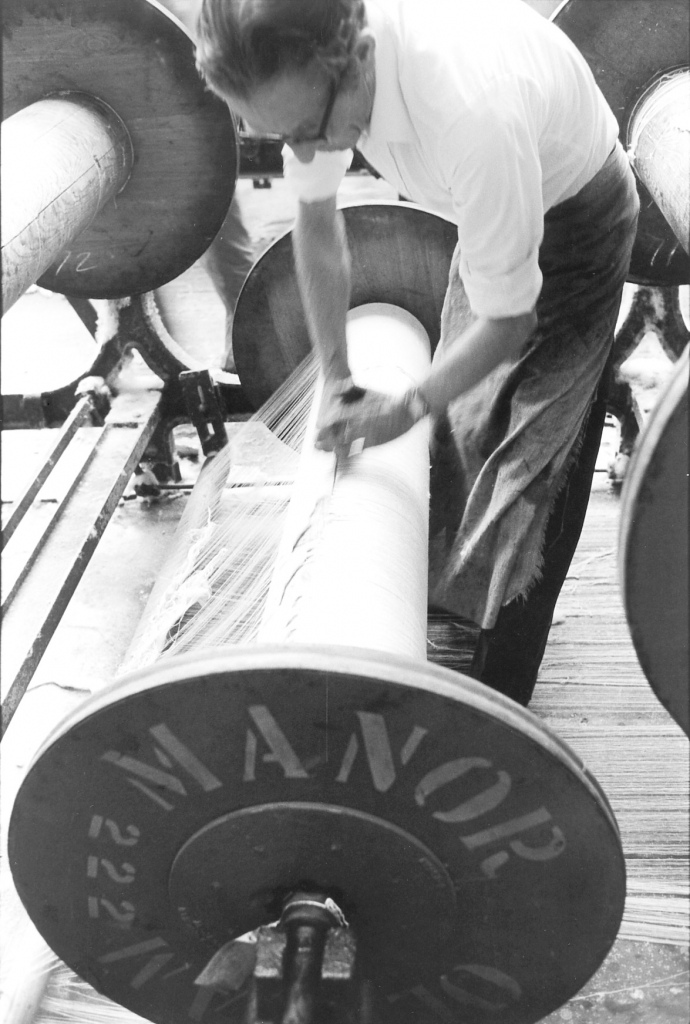

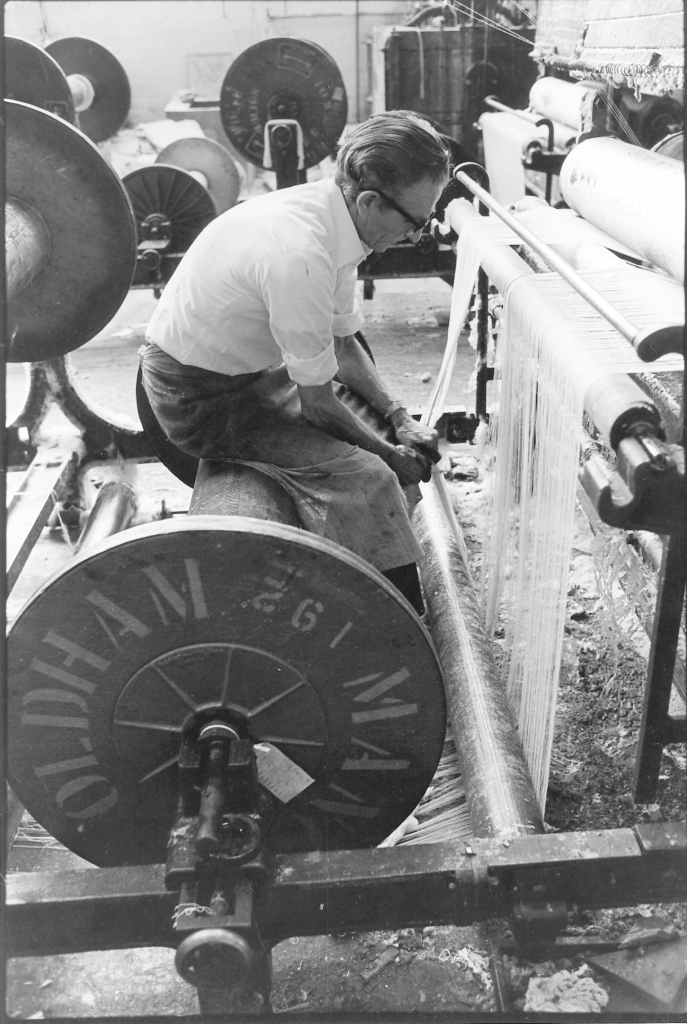

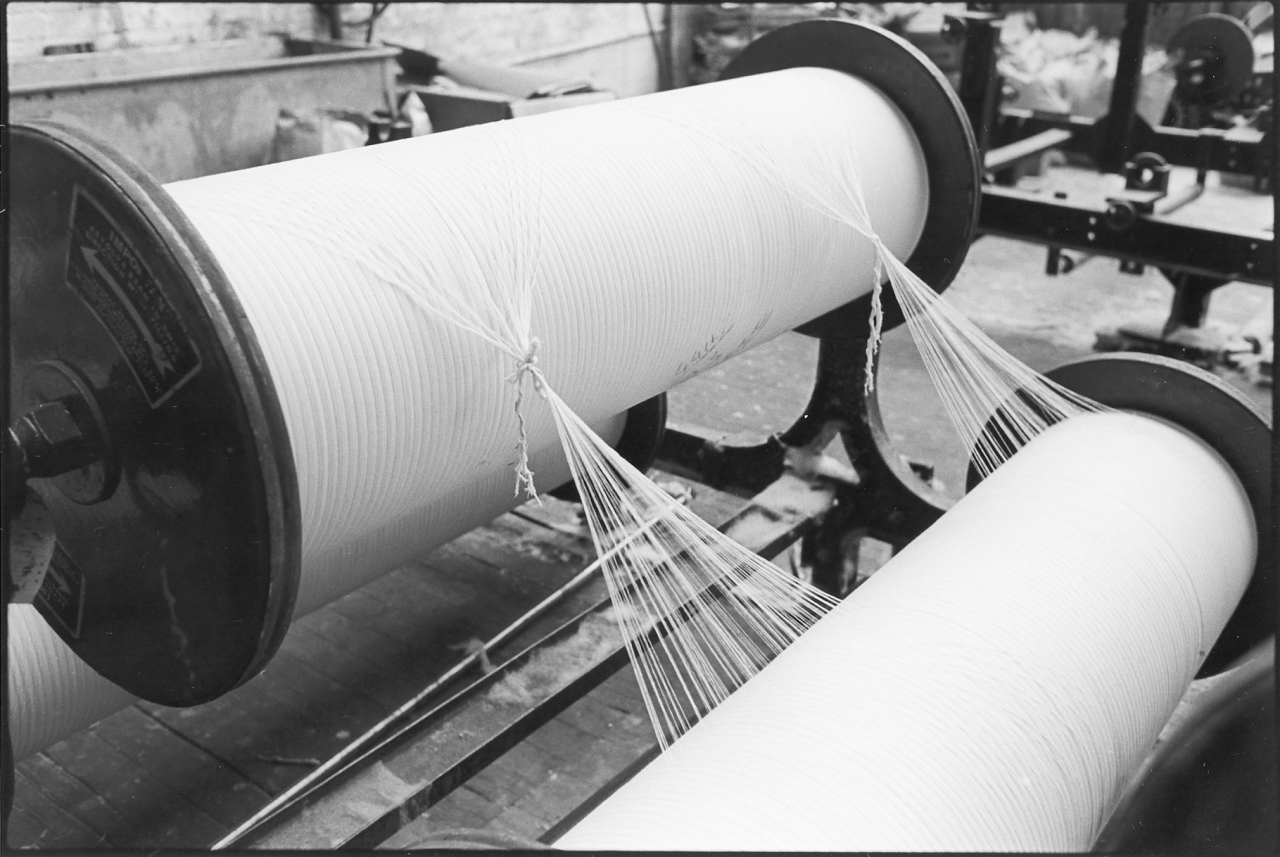

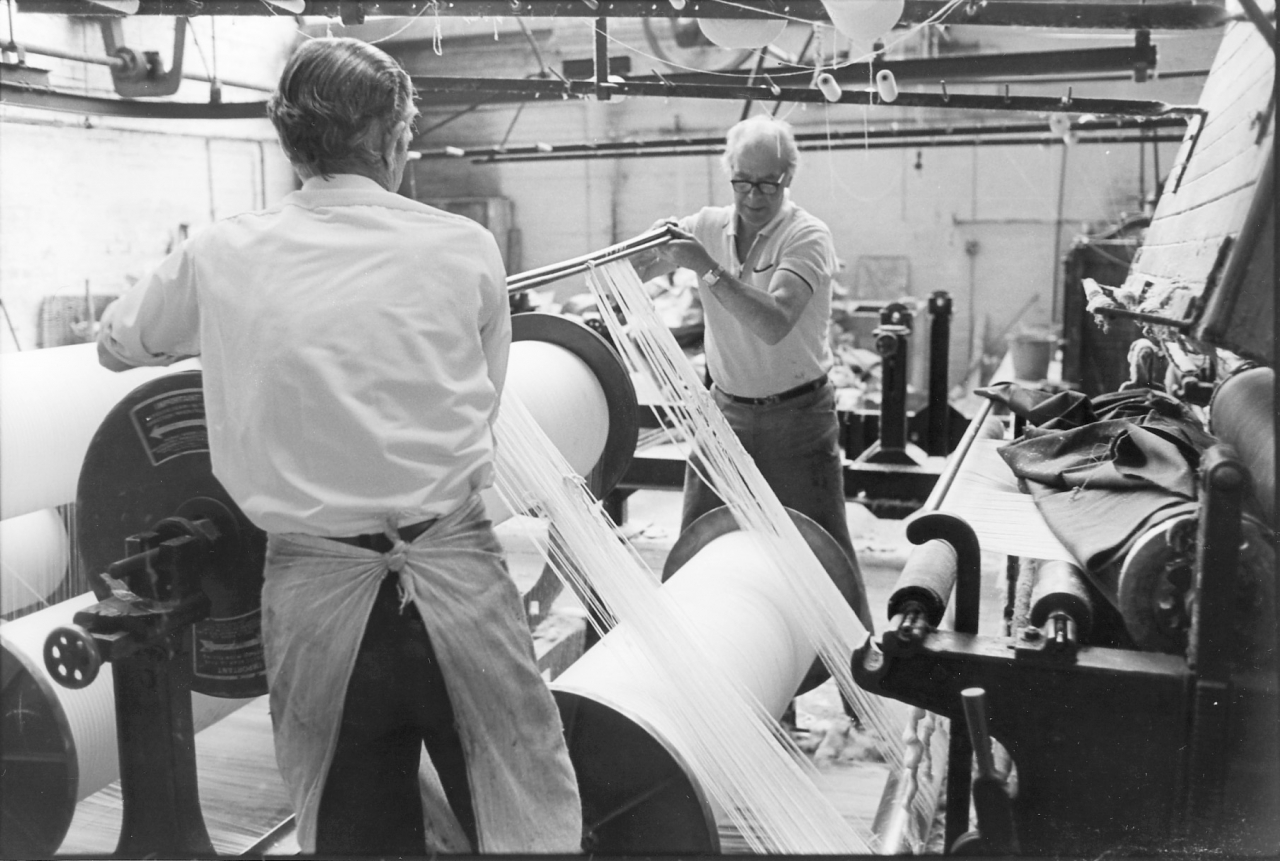

R- Well you’d two headstocks. You know how they were rodded? [Horace is referring to the splitting rods just before the headstock where the individual threads of the warp are separated before they are wound on to the weaver’s beam.] It were split there and one half went on to this beam [In the normal position.] and the other half went over your head, over rollers, over another roller in the air and down here and round another roller and on to your headstock there, you were running two warps at once.

So you were running, say there were 3000 ends, [on a weaver’s beam] you were running two so you were running back beams with 6,000 ends in for your two weaver’s beams.*

R- That’s right.

How many ends did you go up to in a beam on that machine?

R- Well, 3000 on them. But we put 12 back beams in.

Aye, aye, that creel must have been a big un, mustn’t it.

R- Oh aye it were. Twelve back beams on 26 inch beams. And, you know, 26 inch beams are there and then next ones were up there. You’d some work on you know.

Aye. I’ve never seen a tape running like that Horace.

R- And the other tapes, two of the others were 68 inch tapes and they ran two beams at the front. They were split in the middle and you had two narrow beams in and a bearing in the middle that hooked over. And you’ve never seen a tape with two headstocks?

No.

R- Well you’ve been at Johnsons here?

No I’ve never been in a …

R- Oh I thought you’d gone Fred Inman.

Yes but they’ve got that new tape in now.

R- Yes, but it’s a double headstock.

(10 min)

(250)

Well I’d never noticed.

R- It’s a double headstock.

I never noticed, it wasn’t running Horace.

R- No?

No, never noticed.

R- No bit it’s still there because I were in before last …

Aye. Well, I’d never noticed. Shows how much I know about taping! Now you say you went to night school. So you’d start going to night school about 1947.

R- Yes.

And what did you do at night, which night school did go to?

R- Burnley Tech.

Yes. What did you do there?

R- You didn’t learn taping, they hadn’t a tape. I didn’t need learning taping but all, yarn testing, and testing your sago and testing your flours. There’s various grades of sago flour and potato flour and corn flour needed different treatments. And you’d got to know what they’d stand. And yarn and everything, you got to learn all that there. And temperatures and, oh I did a year there.

What, one night a week?

R- Two nights a week, yes.

Two nights a week. Yes. And was there any qualification at the end of it?

R- No.

You’d expect to get the knowledge.

R- You could have sat exams and you’d have got a piece of paper that weren’t worth the paper it were written on because the fellow that were teaching, he’d never been a taper, he were a chemist. He knew all the fine arts and you learned a lot,

(300)

you did. I’m not saying it were wasted time, it wasn’t because same as seeing farina and sago flour and corn flour through a microscope, different things altogether and yet you can pick them out. And different chemicals that you use, and if they are adulterated, all such as that.

New that’s got you started at Johnsons. Now I want to just back track a little bit now, there’s two thins I want to know about, and then we'll go on to taping at Johnsons proper. Now the first one is that, of course by the time you started at Johnsons, cloth wasn’t sold by weight any more, it was sold by the length. Anyway, they were weaving for themselves like. I mean it’s obvious they weren’t heavy sizing there. But while you were at Rycroft’s you’d see something of heavy sizing.

R- Every sort but mainly at Slingsby’s. 100%, everything at Slingsby’s everything was 100%. They sold be weight at Slingsbys you see for export, and they wanted 100% weight of China clay to cotton. And the warps, they’d some stuff at Slingsby’s and it were tens. [count of the yarn] There were that much size on them that the tapes couldn’t dry them. They [were wet] couldn’t, well, God knows what you’d got, wet into the loom. And when they were weaving they hadn’t dried, it were rubbing off same as balls of sago and at the end of the day they’d to rub all these balls of flour

off the healds.

(350)

Aye.

R- Oh, and I were in the warehouse. You couldn’t lift them out of the machine, you just dropped them down, they'd just drop like lead, 100 yards of that stuff. And they were wet. And then they were sending them away, they were mouldy. So you get on to Shirley [and ask] what do they do. Well, Shirley had a cure for it.

That’s the Shirley Institute of course.

[The Shirley Institute was established in 1919 as the British Cotton Industry Research Association (BCIRA) and the following year the current Didsbury site near Manchester was acquired. A significant part of the purchase price was contributed by a cotton spinner, Mr W. Greenwood, who asked that the place be named after his daughter Shirley. The first purpose built laboratories were opened in 1922 by the Duke of York. Other Royal openings on the site took place in 1953 by the Duchess of Kent, 1963 by Princess Margaret and 1990 by the Princess Royal]

R- Shirley Institute, aye. You put Shirlon on, it were some stuff they sent, Shirlon they called it, and you put it into the beck [The beck is the tank used for mixing up and boiling the size before it is pumped to the sow box on the end of the sizing machine in which the yarn was immersed before going on to the drying rollers.] when you were mixing, and it would stop your mildewing. But it didn’t stop them rusting, because it didn’t dry them but it stopped mildew. You can imagine those [pieces] being folded up and going all the way to Manchester and standing in [storage] for a month or two happen, and going on board the ship. Oh, they were just moulded in lumps, green. And they moulded, they’d mildew standing in the warehouse at Slingsbys. But Shirlon stopped the mildewing but then they used to rust in the looms from Saturday to Monday, on the bearers, and everywhere they touched iron, in the temples, they all rusted. And you used to mix salts of lemon [Archaic name for Oxalic Acid] in boiling water and turn the piece over, lap by lap, and rub the mildew, the iron moulded place, with salts of lemon to get it out, and that’s what used

(15 min)

(400)

to be [done] every Monday morning. Where they’d been stopped there were those rust marks.

Now, that wouldn’t be too bad really, for those in the shed, because you wouldn’t get a lot of dust flying off those warps.

R- No there weren’t dust off them but there were off the others.

Now that’s what I’d like to get round to. Let’s make it clear for a kick off. Now you tell me if I’m wrong, that the only reason for putting China clay in size on a taping machine is to bulk up the cloth and give you more weight isn't it? It doesn’t do anything else to it.

R- Yes, selling China clay for weight you see instead of cotton, that were all it were for. And you’d got to get the weight, they were sending it back from Manchester because they weren’t heavy enough. They were selling it by weight were the merchants at Manchester. And another thing we did, we’d get buckets of size, any that were underweight, you can get buckets of sizing, warm sizing from the tapes and you’d turn laps and you had a whitewash brush and you, you patted it on all over it. And then turn another two or three laps over, paste some more on as if you were pasting wallpaper. It’s unbelievable isn’t it.

Aye.

R- Till you got your weight. You couldn’t credit it but I’ve spent scores and scores of hours doing that, stand at a table, turn the laps over and paint it on with a brush.

Just to get the weight up.

R - Paste it, paint it ... just to get the weight. It were China clay, just China clay that you were putting on.

(450)

Aye. Now tell me about 100% sizing or getting on for it. Where the warp was dry . Now what effect did that have when they were weaving it?

R- Well, if things got too dry at Slingsby’s they put wet steam in.

Ah now, yes.

R- You know what wet steam is, humidifiers, blowing the day through. But that did for the ordinary [sorts]. But there were D1’s I remember the quality, D1, [the sort number used to identify the warps in the shed.] it were one particular sort. It were heavy sized and in dry weather if the east wind were blowing they were flying out in bunches, and so they had the humidifiers going all the time. But these that were already damp, it made them worse than ever.

Now, just let me ask you a question there now. This is something that I’ve come across time and time again, the fact that .. you know, one of the things that they say about .. they say that one of the reasons why Lancashire was always such a good place for weaving cotton was because the atmosphere was naturally damp. Now it follows on from this that, if you talk to people, the place that was always favoured for a weaving shed was somewhere where they could sink it back into the hillside so that the walls and floors were always damp, you always got a damp atmosphere. Now people have told me, I have them on tape telling me, that in some cases they even went to the extent, for instance at Barnsey Shed in Barlick in summer …

R - Throwing buckets of water?

They used to pump water out of the canal on to the floor of the shed.

R- Yes, they used to throw it in bucket fulls. Yes you send t’warehouse lads round with a brush sprinkling it on between the looms.

Now then, tell me something. I started off believing

(500)

(500)

(20 min)

what I’d always been told. That the reason for this, the reason why they liked the damp atmosphere was that it made the cotton weave better and stopped the individual threads in the warp breaking. Now then, I began to realise, as I started to learn more about the way the textile industry had been run, that what it was really about was that the manufacturer could get away with using cheaper weft and cheaper twist, because with being damp it didn't break as quickly, it was more elastic. But it seems to me now that what you’ve just told me there is another reason for it as well. The damper it was in the shed, the less size came off while it was being woven and the more weight they got in the warp. Now is that right?

R- Well, not altogether, that wouldn’t make much difference in the ordinary heavy sized cloth, the loss wouldn’t make much difference there. But it made cheaper cotton, it made poor cotton that had been sized weave when it were damp. If it was sized, if it was China clay, then when it were dry it were brittle so it had to be damped with the steam to make it pliable.

Aye.

R- And if you put more tallow in to counteract it, your warp is too soft, then it rubbed off. You see it were too soft. But in cold weather it were too hard, dry east wind drying everything up, they were flying out in bunches. But it were to make cheap cotton weave because Rycrofts had no humidifiers, theirs didn’t need anything to make them weave. They’d weave full warps without an end down. They couldn’t have ends coming down when every end had to be sewn in.

[To make the point clear, Rycroft’s yarn was the highest quality long staple yarn and was the easiest to weave. For many years, Surat, a type of Indian staple, was regarded as unweavable. It was the need to drive down material costs that led to the innovations in humidifying sheds that made this possible.]

Aye. So would it be true to say Horace that heavy sizing was confined to what you and I would call rag shops?

(550)

R- It was. Heavy sizing were confined to rag shops, cheap cotton, to make poor cotton weave. They put the sizing on and if they didn't have the humidifiers in they wouldn’t weave. But they had to put the sizing on. They weren’t content with just having pure size, they'd put China clay in to sell China clay.

To fetch the weight up.

R- Yes. To fetch the weight up.

[To reinforce this, Horace is giving very valuable evidence here about the strategies used by the manufacturers to maximise profits. The addition of china clay to double the weight of the cloth and the consequences of this in the shed. It should be added here that the merchants demanded this heavy sizing because the ultimate judge, the customer, bought on cloth weight. The point about humidity and the weaving of short staple yarn is well made and reinforced. The reference to Rycroft’s not needing artificial humidification is crucial, they used top class yarn. As a matter of interest, Bancroft Shed never had humidifiers. It was built into the hillside and on top of a peat bog.]

Yes. Now then, we’re talking about size now. Now I’ll tell you what I know about it and you tell me some of the things that I don't know about it. The only size that we ever used at Bancroft, because we were on very plain sorts of cloth up there, the only size we ever used up there were tallow and farina which is potato starch.

R – Potato starch. It’s rubbish is farina.

Well we used tallow and farina and every now and again I think they would put a bit of soft soap in, if it started sticking to the drums because they were in a ropey condition them drums up there.

R – Yes.

And that was all we used, but I know that .. I know enough about the job to realise that that is only the beginning of sizing, isn’t it. Now you tell me something about sizes.

R- Well they only, for all the stuff they used here…

That’s at Johnsons.

R- At Johnsons. For the cotton all they used were pure sago flour and the best tallow, for the cloth here, nothing else, for their ordinary plain stuff. But for the very light stuff, the gauzes, they used Gum Tragon, that comes from Cyprus, locust bean flour. Do you know what locust beans are?

[The standard work on sizing is ‘The Chemistry and Practice of Sizing’ by Percy Bean. Bean differs from Horace in that he says that Gum Tragacanth (or Gum Tragon) is the ‘ gummy exudation from astralagus gummifer and is obtained by making incisions in the stem of the plant and collecting the sap’. He describes a ‘comparatively new material for sizing which is manufactured by the Gum Tragasol Supply Company Limited of Hooton….. the gum is prepared from the kernel or seed of the locust bean, or St John’s bread, the fruit of the carob tree, ceratonia siliqua’. This was sold as Gum Tragasol or, in dry powdered form, Gum Tragon and this is what Horace was describing Any mention of ‘tragan’ in the original transcript is a mis-transcription .]

Yes.

R- They put them in troughs to feed the sheep on it used to be.

Yes, that’s it. Used to bind in water. Aye.

R- Yes. Well there’s a little brown bean inside.

There is, right little hard bean.

R- Yes. Well that’s what they use for Gum Tragon. It’s Gum Tragon is that.

(600)

(25 min)

Is that Gum Tragacanth, is that what it is?

R- Gum Tragacanth, yes. Aye, locust bean.

Ground up, aye.

R- Yes. And they’ve got to get rid of that husk. Chemicals won’t touch it, nothing’ll touch that husk. So they're put into big drums, with, whether it’s rough inside or there’s something to mix and they go round and round and round.

Aye, rumbled.

[Horace is talking about a ball mill or a variant thereof. The beans would be mixed with abrasive matter in lumps and rumbled round in what was almost like a butter churn. The collision of the abrasive material and the beans removed the husk.]

R- Rumble until that husk comes off. Now sometimes it doesn’t come off so they have a lot of machines, they have a magic eye on them. They put them on top, they come down a chute and anything that has the least bit of brown on, the magic eye throws them out. That is before they go on to the next process to be ground up for Gum Tragon. And there’s a place on the Wirral that does that. It’s marvellous to go to that place and see them rows of these magic eyes…

Have you been there?

R- I’ve been many a time.

Aye, what's the name of the place?

[Hooton]

R - I can’t think. I can't just think what it is.

It'll be reight ...

R- I could get to know down at the mill because the name’s on the bags that it comes in. And you can use it for wallpaper.

Pasting wallpaper?

R- Yes, and I’ll tell you what it is, it’s used in ice cream. It’s used hair oil, anything that wants keeping in suspension, Gum Tragon is used. There were about quarter of an ounce to a gallon in ice cream, they told us all so, foreman at this place went on. But It had to he the very purest for ice cream, but not quite as pure for taping. But you see when you used to

(650)

get bottles of sauce, the vinegar were at the top and the sauce were at the bottom, but you don’t see it now because it's Gum Tragon keeps it in suspension.

Aye.

R- Brylcreem, they are a big supplier to Brylcreem [hair cream] and Wall’s, Lyons, [Ice cream manufacturers] they are the firm that supplies the Gum Tragon. And They’d difficulty at getting it during the war you know, they’d a lot in stock but it got to be scarce. A man probably had a orchard of them trees, locust bean trees, and there’s some law that a man can’t leave it to the eldest son, it’s all to be divided out. [partiple inheritance] Well if a man had ten sons and he’d a hundred trees, well ten sons would get ten trees each. And then the next generation come on there’ll happen ten sons’ll get down to one tree. So they’d be negotiating with each of them separate persons for the crop. The locust beans, it was such a mixed up affair in Cyprus. And he [the firm’s representative] said you didn't know who you [were dealing with] We used to go there and you’d, you went into a room and he’d tell you all the history of the locust beans and all about it. Oh it were all right, coach load, coach loads of us used to go. The Union [arranged it]. And [it were] a right nosh-up and as much beer as you wanted to drink, and a feed and everything. Of course, we were their best customers. If a taper said “Don’t get no more.” Or if you’d had a good do, well you put a extra bit in you see? That’s what it was all for but it were really interesting. We had some right good trips out. And another firm we used to go top regular was Scapa at Blackburn. [The Scapa group in Blackburn was an amalgamation of Scapa Industries with Porritts and Spencer Ltd who were an old and well established firm specialising in weaving very wide and heavy flannels for the textile and paper-making industries. In 1999 following the acquisition of the majority of the shares by

Voith Bespannungstechnik GmbH, Germany, PSA came under the Voith Group.]

(700)

(30 min)

Aye. Scapa Porritt? Aye.

R- Scapa. Weaving cloth 45 feet wide. Now then, woollen cloth 45 feet wide. You can’t tell me what they were for.

Well .. I don't know, it must have been for, I was thinking for like tape flannel and such an that.

R - No. Paper making machinery.

Aye, that’s it

R- They’re as long as a railway train is a paper making machine. And it’s mixed up into a pulp, same an we do sizing, and it’s run onto these cloths, it’s made into an endless belt.

Aye. Onto a blanket. Aye.

R- Aye. And it’s running over hot pipes and the slurry is going out on to the top. And then it’s rolled off at the other end as paper 45 feet wide. And it goes on to various sets of these, some of it’s asbestos, the first, the first what it came on top of, the hottest pipes, [the blanket] were asbestos mixture, asbestos and cotton, then it went on to the woollen blanket. And he said if you looked at the paper you can see the pattern of the blanket on the back.

Aye, the pattern of the weave on it. Yes.

R- Aye. But, oh they were weaving stuff half an inch thick, this asbestos. It weren't all 45 foot wide, but one man had just a loom and he were up, one loom and he were up on the platform. And you stood at the end of the loom and there was a big guard up and the shuttles had wheels on, rollers on and it was just same as a rabbit coming down. You’d see it start at the far end, you could see it, just like a rabbit coming down. And one weaver said to me, “Just watch this”, and as it were coming along he just had his hand there and he let it run up his hand and up his arm. a big shuttle about so long. [24 inches] And he had the other in his hand and just threw it in, the loom never stopped. And shuttle ran out up here, he just threw the other in.

(750)

He changed the shuttle with the loom running?

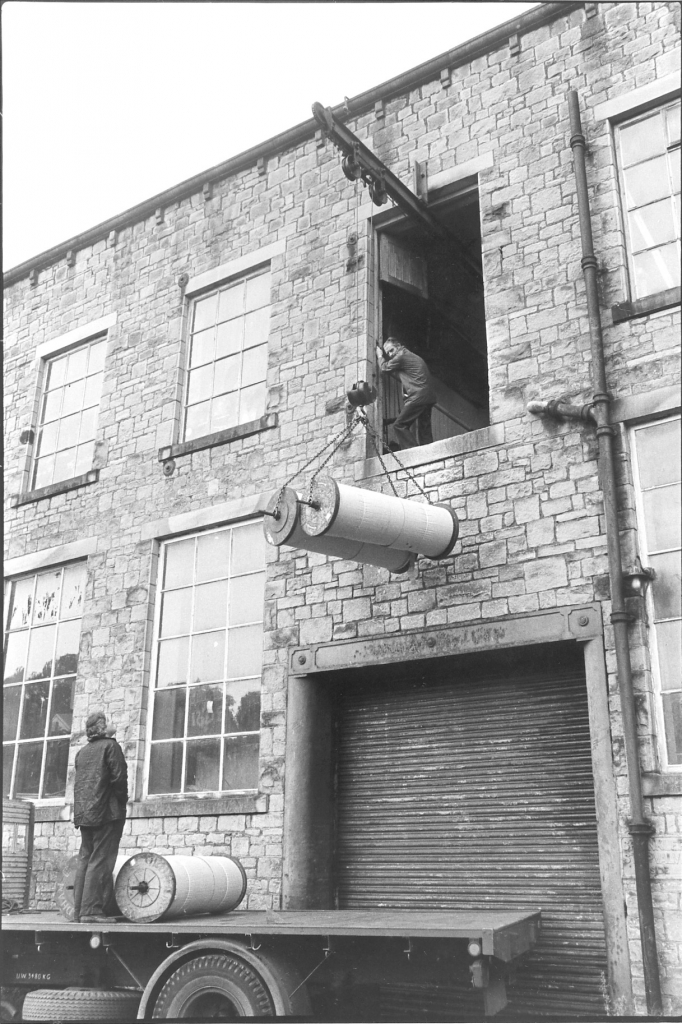

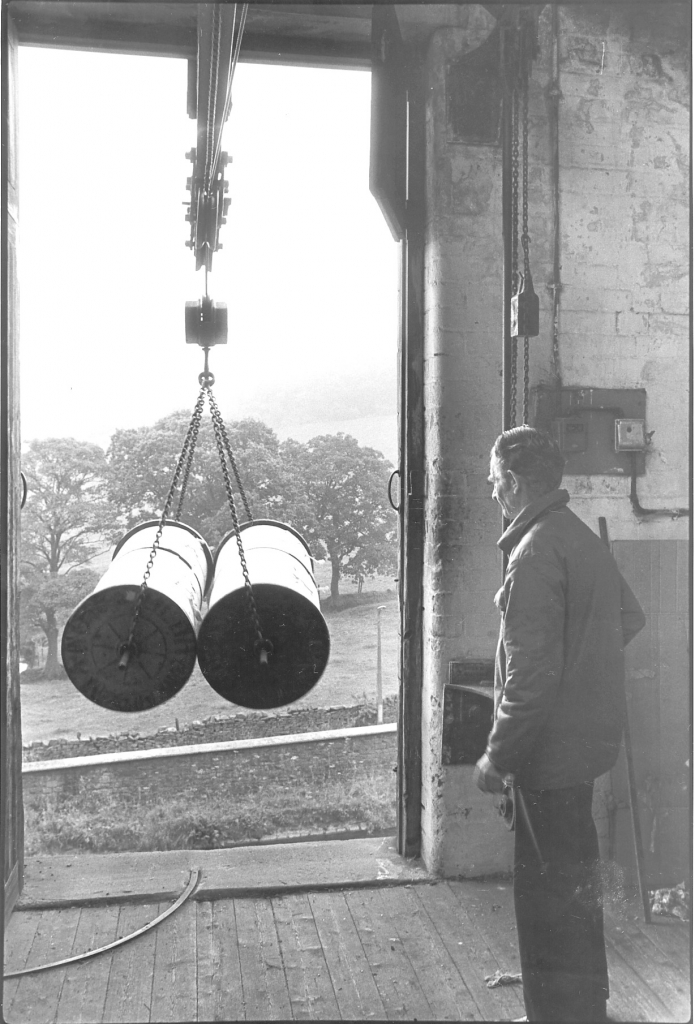

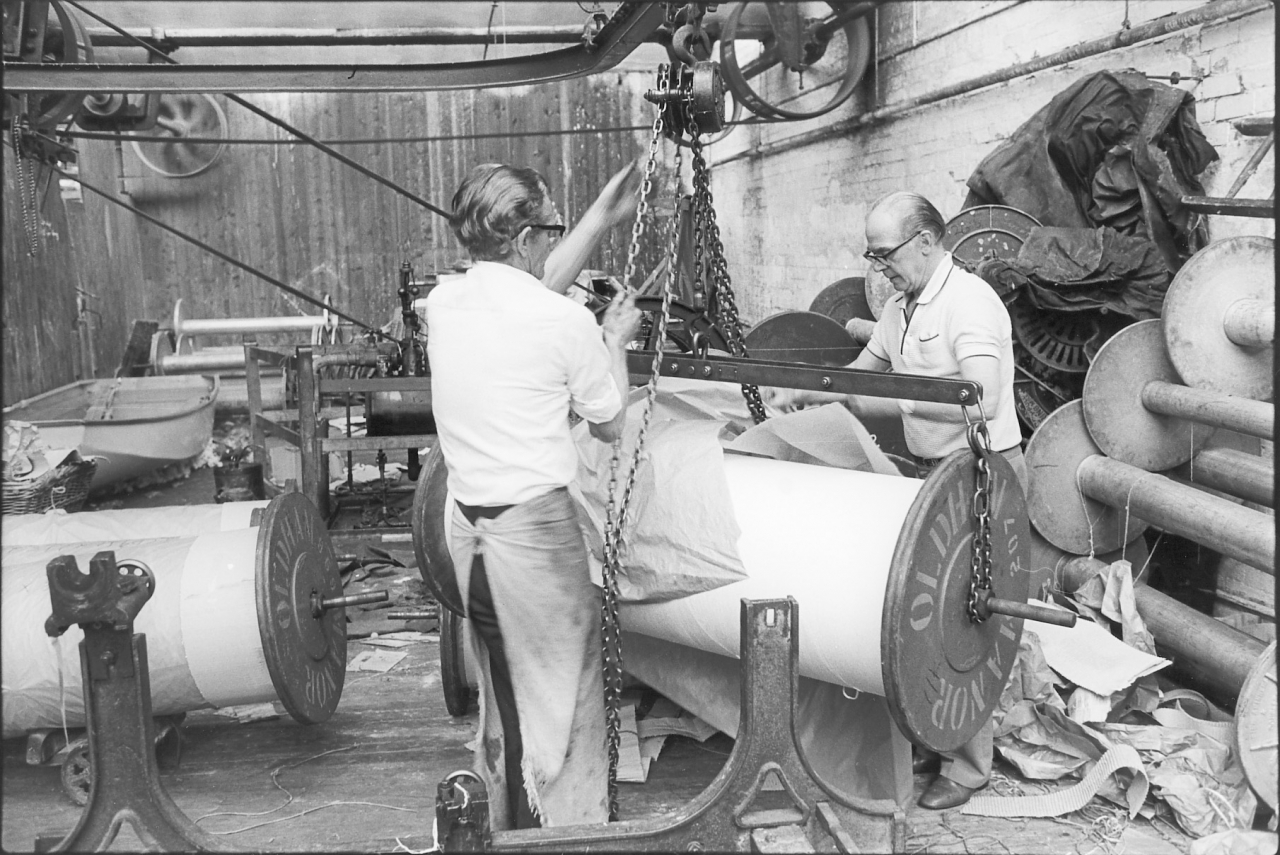

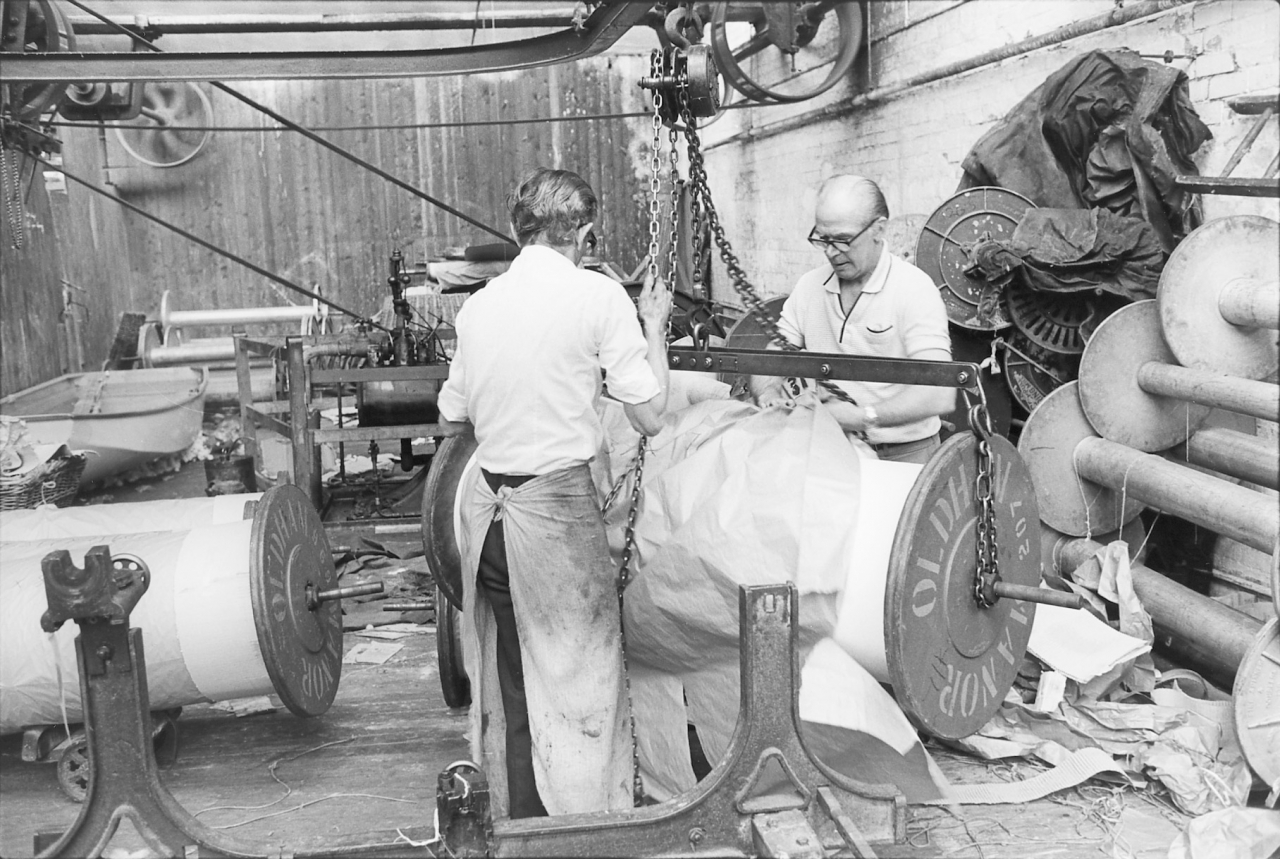

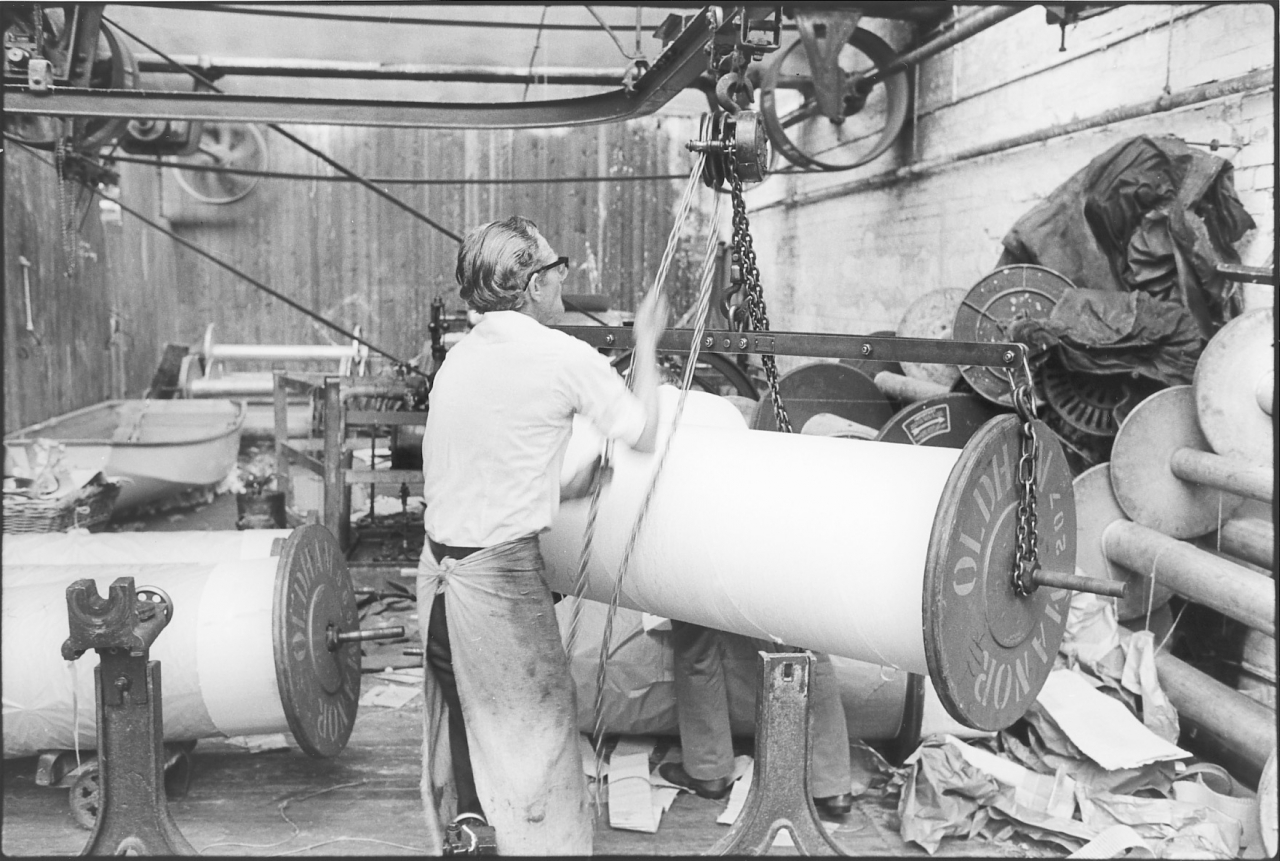

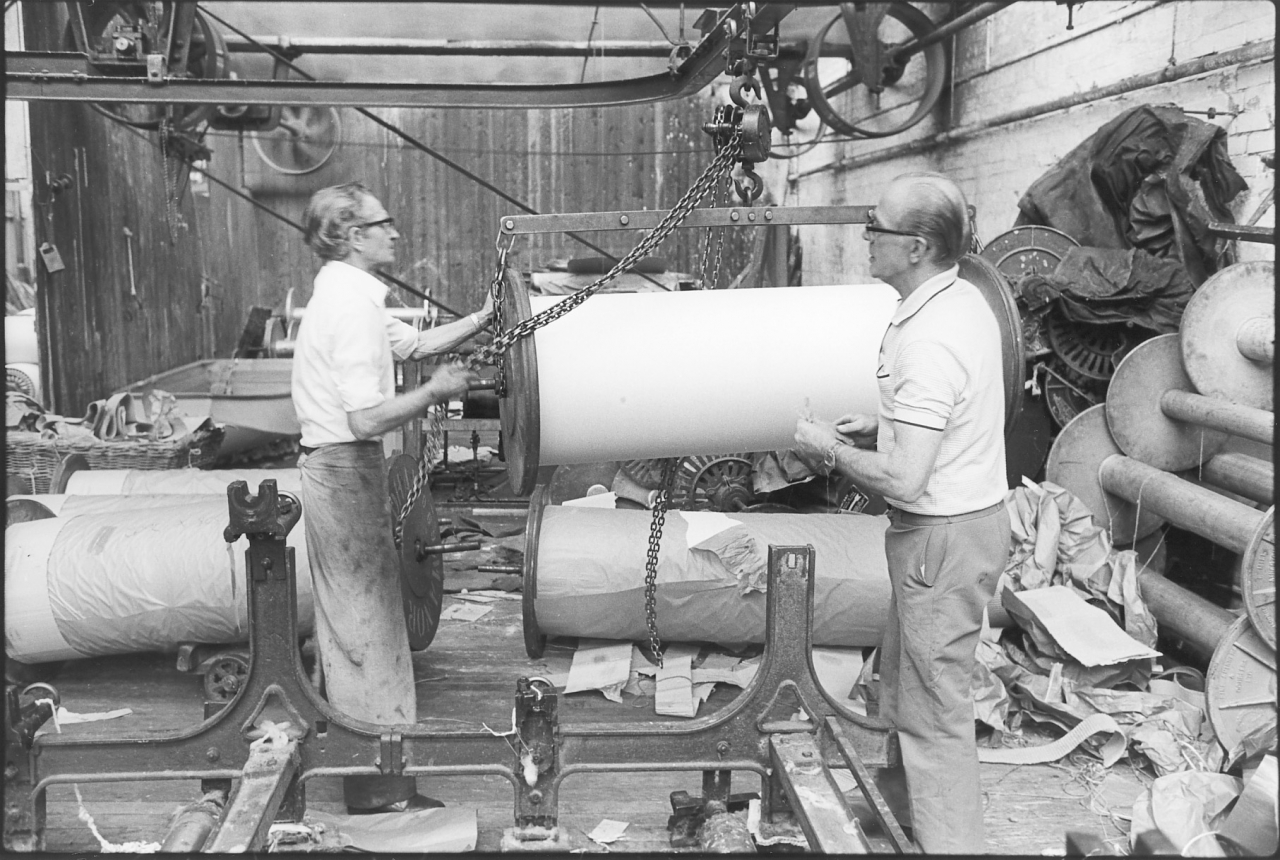

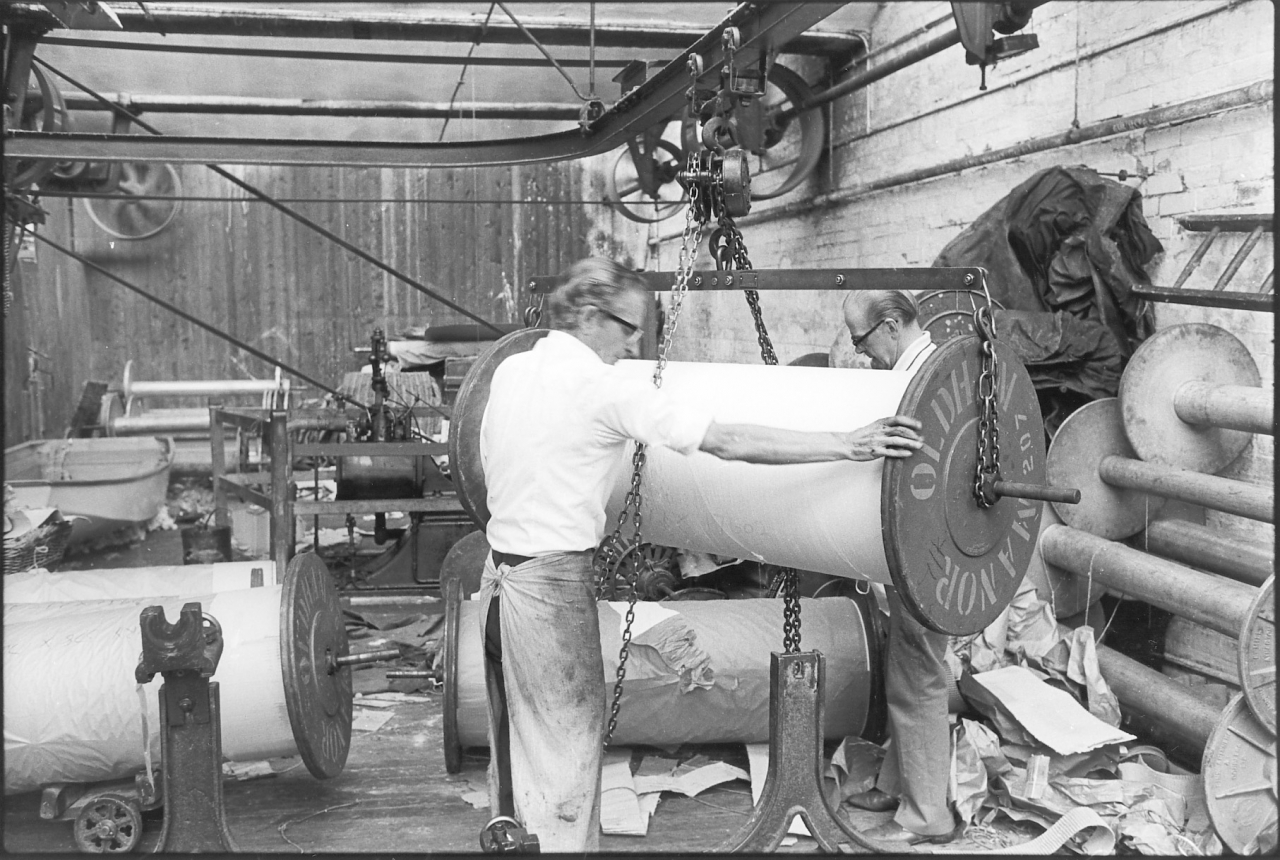

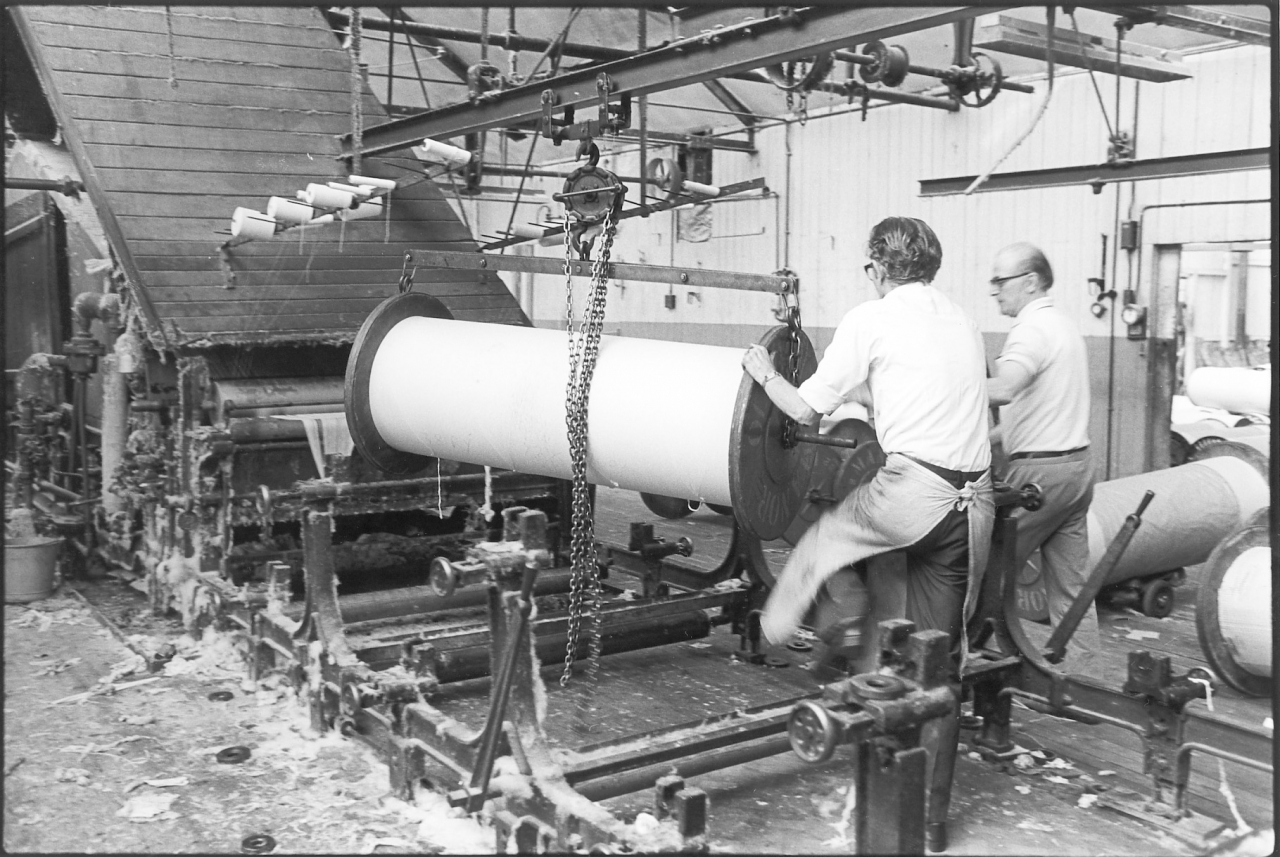

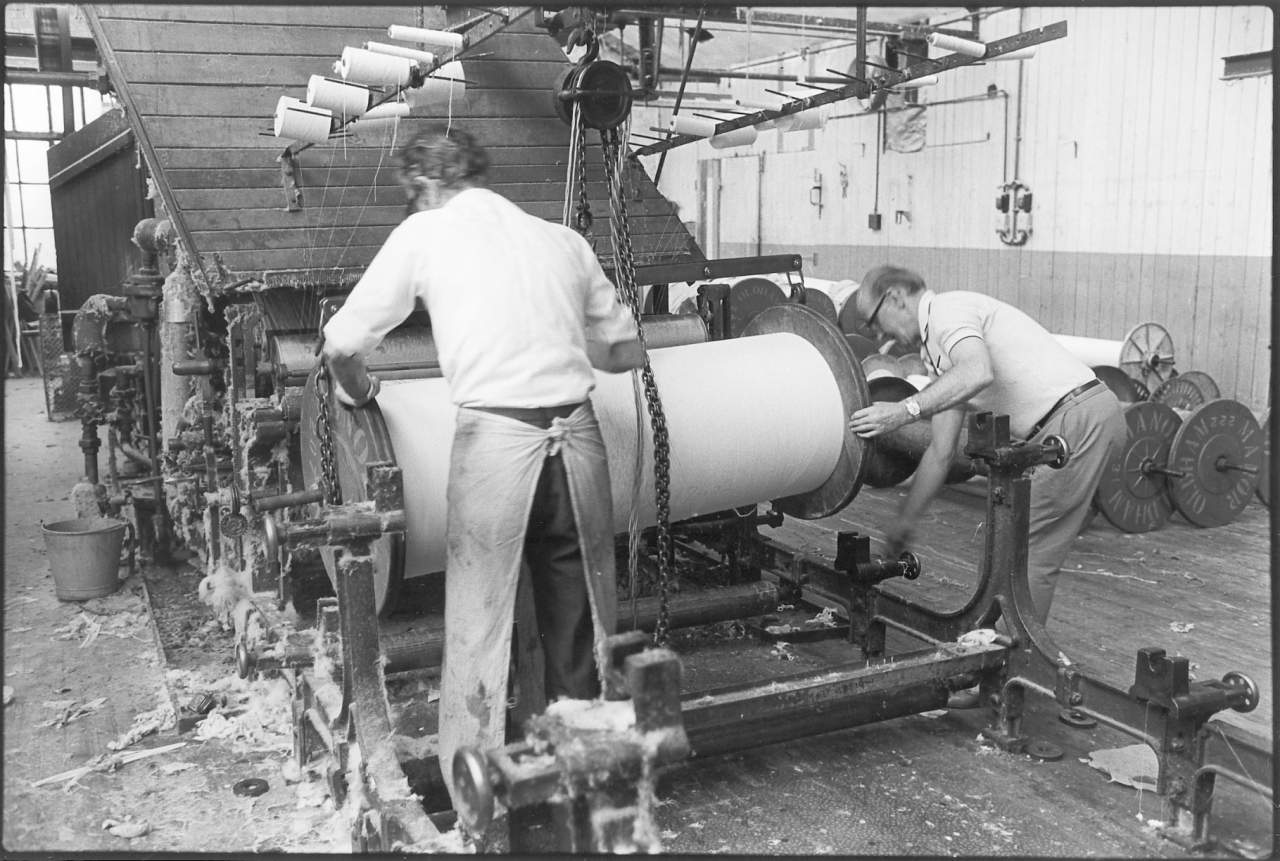

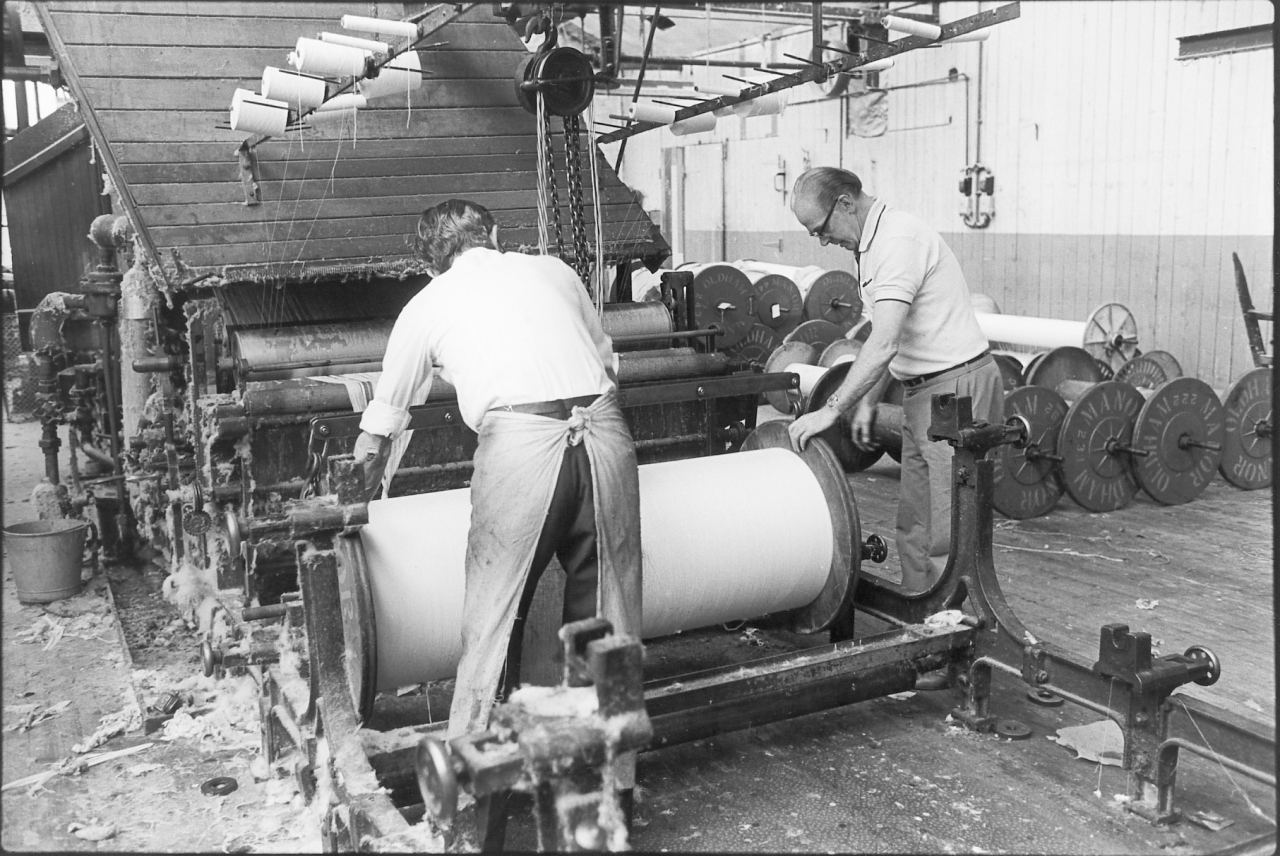

R- Loom running. He says “You won’t have seen that before!” But I was stood at the end and I was just on a level with the slay and the warp. I don’t know how many warps would be put into that, but they were hollow barrels and they were all done with a crane. They lifted this steel barrel out and they put these beam, warps, on at the back, and filled the roller up, 45 foot wide, bolted them all on and then craned it back in and then a chap sat in the loom, looming them in.

I see, they loomed it in place.

R- Yes.

In the loom.

R- And on other looms they didn’t even have warps. They’d creels and they never stopped. They put a fresh bobbin in and the weaver went round tying the ends in same as a beamer did on an old-fashioned creel. He went round the back tying bobbins on, they never broke, it was such strong stuff.

Aye, like they were continuous ends. They never [went down]

R- Ye, never [stopped] And they’d menders, when this cloth came off these big looms it went down under the floor and up this side and on to a big roller. The taking-up motion was there. It wound on to a big roller, they wove one hundred yards in a length and then craned it out. And women were mending it on an endless belt, same as splicing it, same as a burler and mender does. They were sewing every end in for paper making. They were going all over the world, they were packed up. Talk about an eye-opener! We went many a time to that, usually a trip a year you know.

Oh I shall have to go and see that. Because they’ll still have them looms running.

R- Oh they will. All paper making. It’s somewhere near to…. There’s a park there.

Aye, it’s just below Pleasington.

R- Aye, but there’s a park there. Where do they play football? I heard it only the other day on Radio Blackburn. That’s practically, it’s near Scapa.

I know where Scapa is.

R- Well, you want to go if you can get in.

Oh yes. I shall have to have a look at that. Aye.

R- Oh it’s a real eye opener. And they’d a foundry, they made all their own looms and castings because they’d to be so strong.

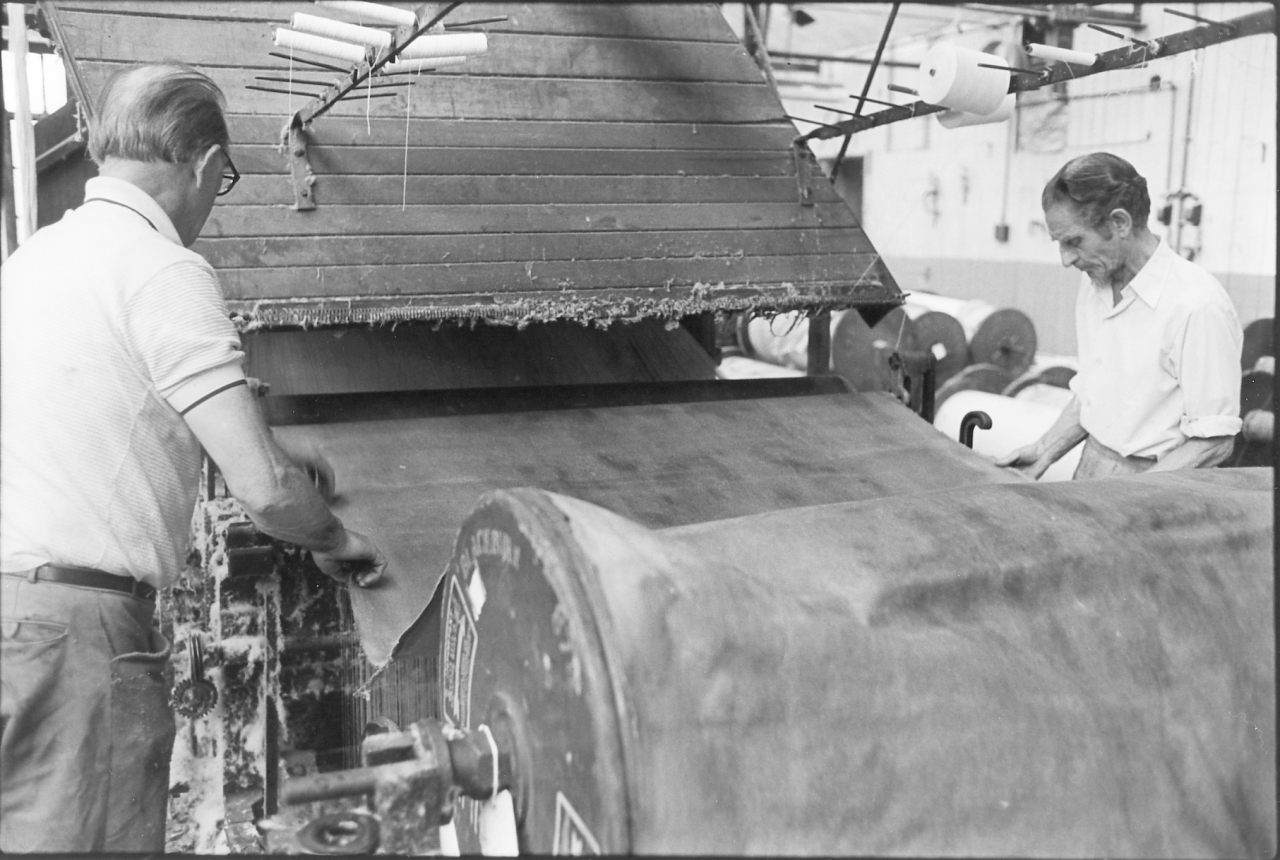

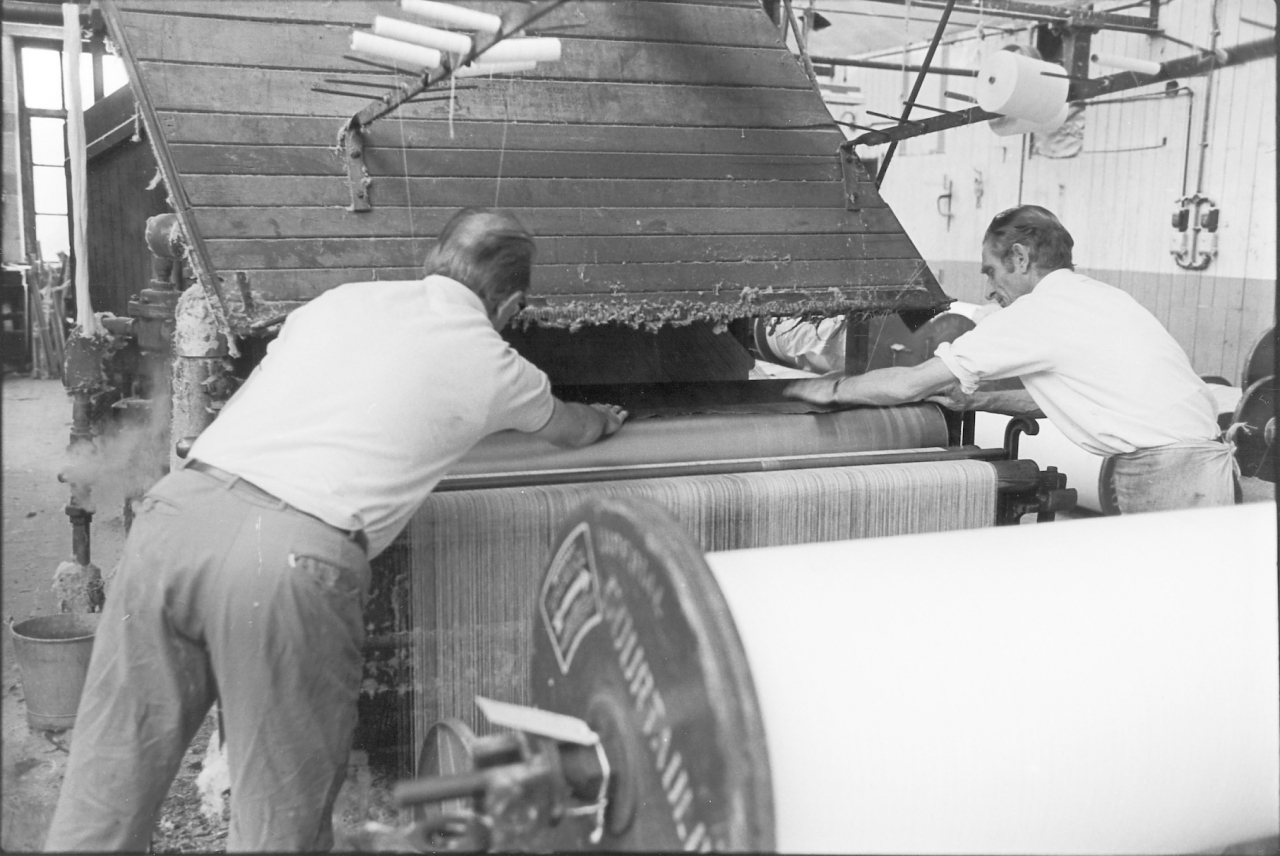

Aye, a loom 45 feet wide. Anyway, that brings us on to something else. They’ll make ordinary, well what to us is ordinary taper’s flannel wouldn’t they?

R- That’s why we got to go, we were using their flannel you see. That’s why tapers were invited.

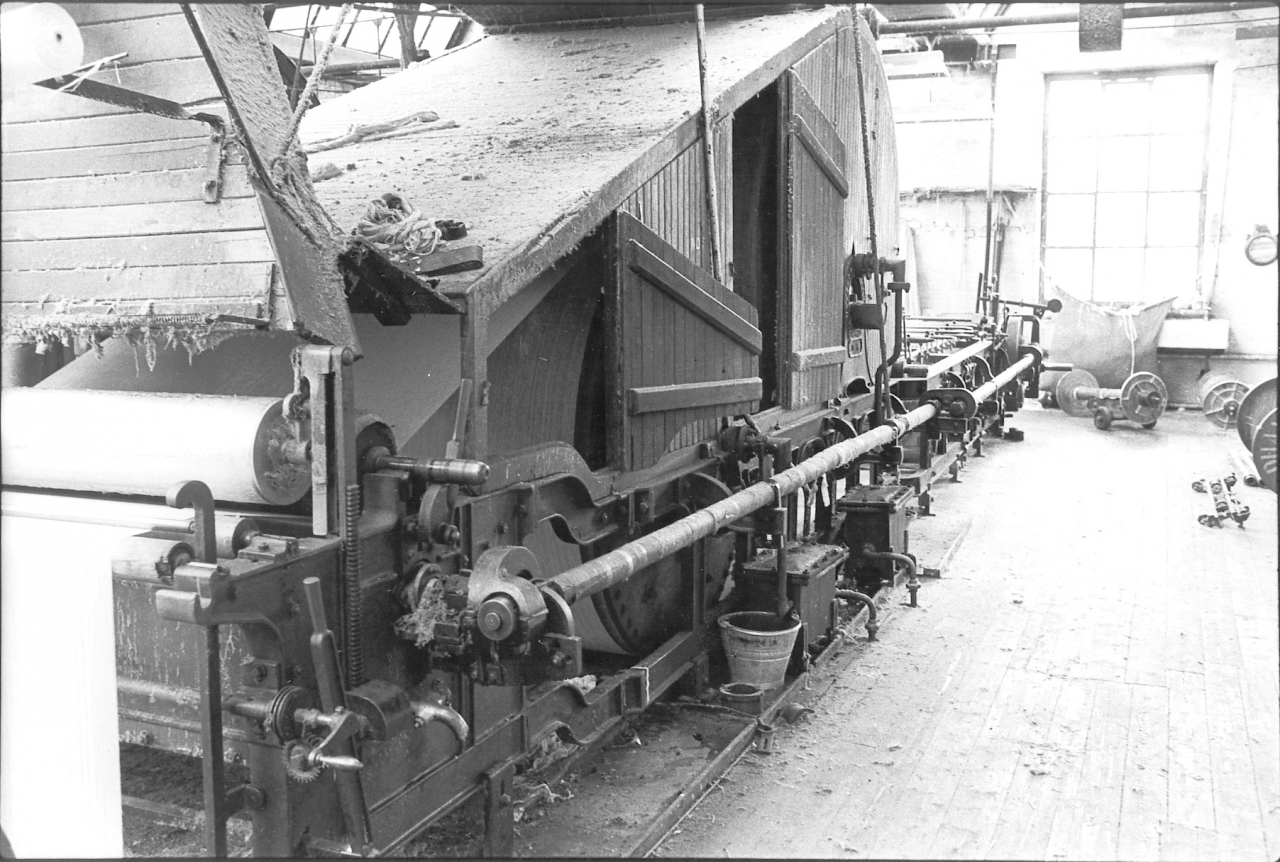

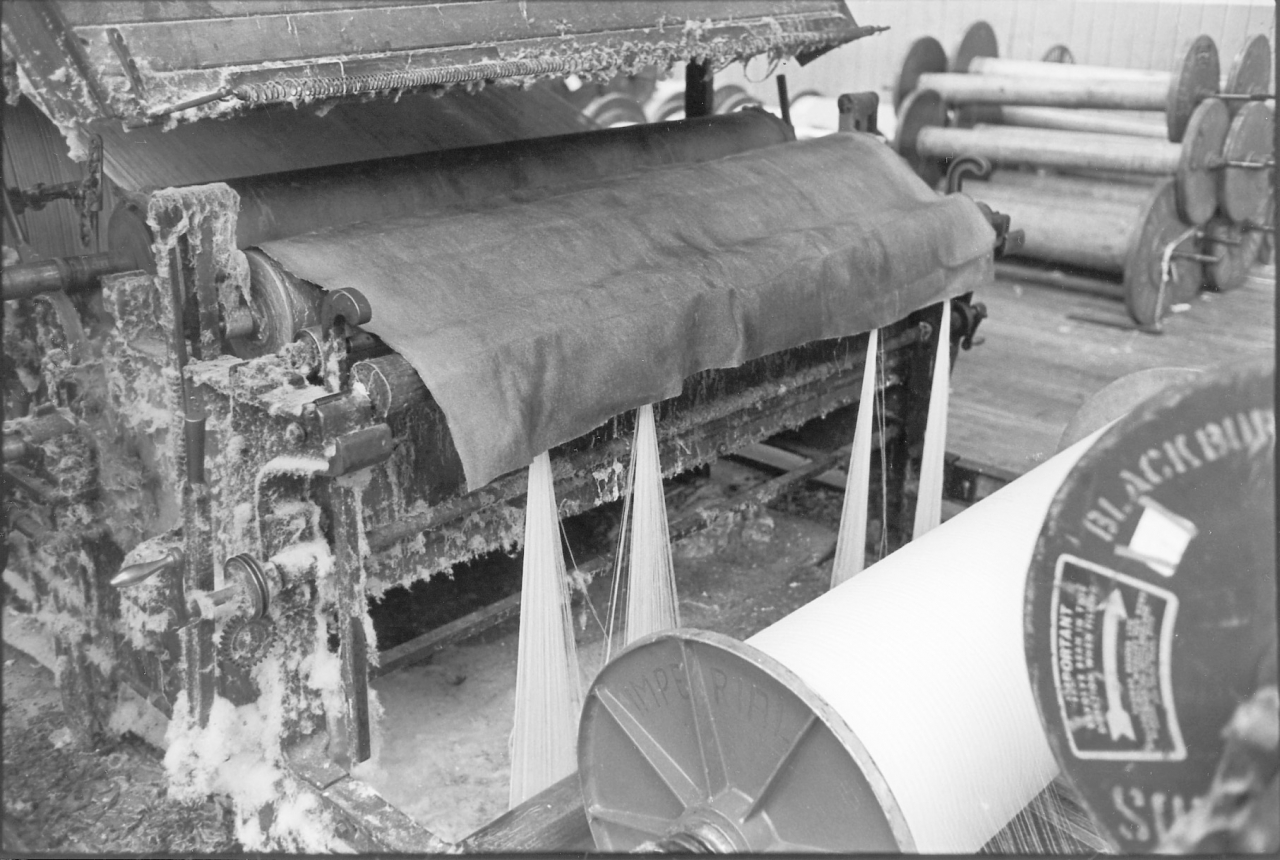

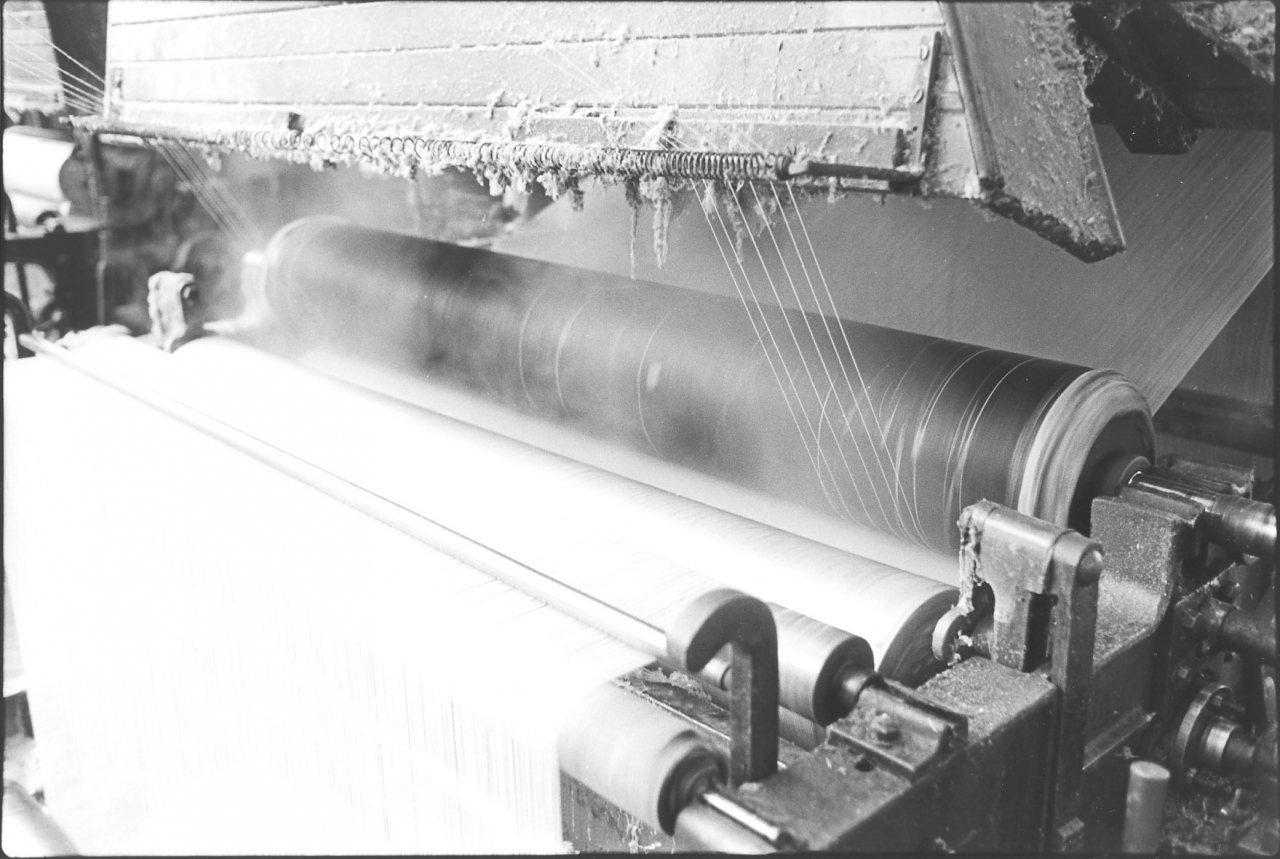

Now tell me a bit about taper’s flannel. What’s taper’s flannel used for on the tape?

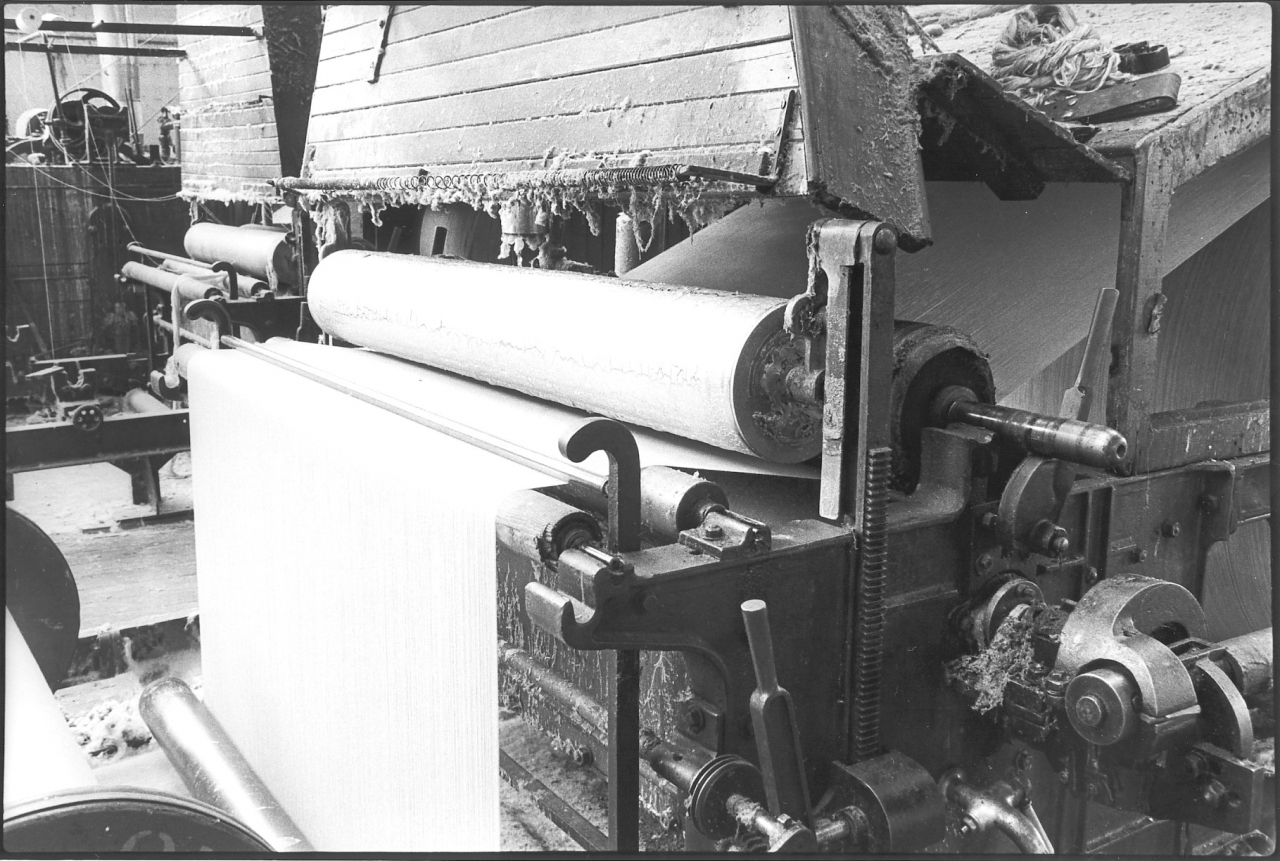

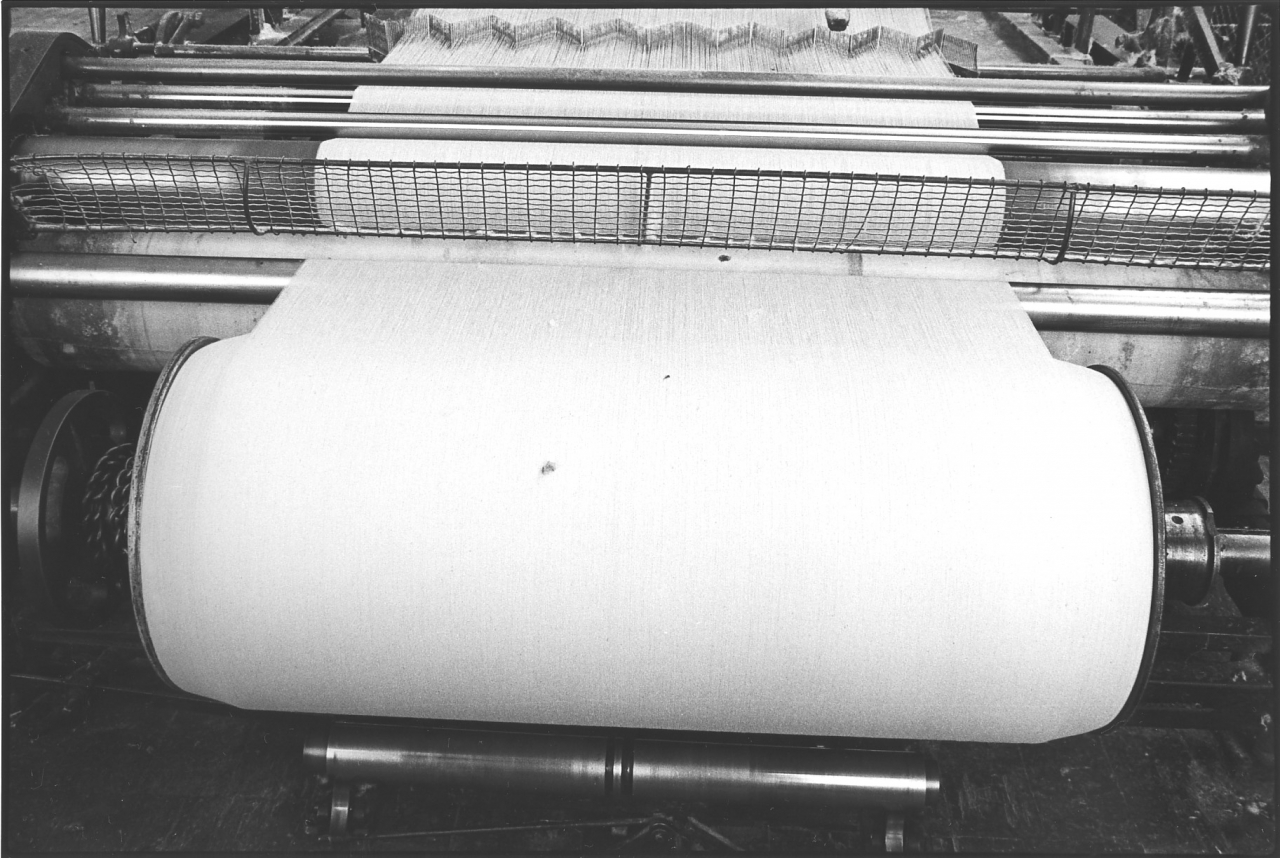

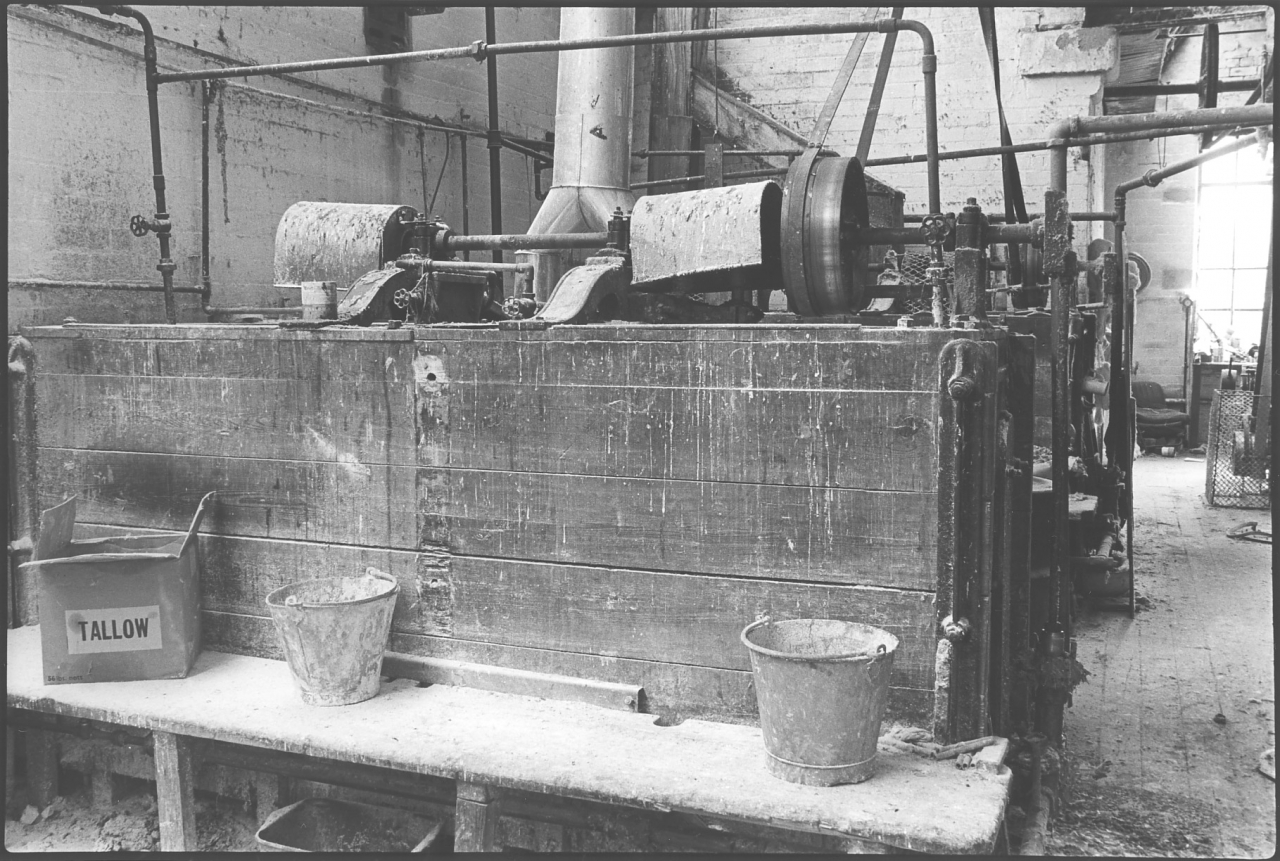

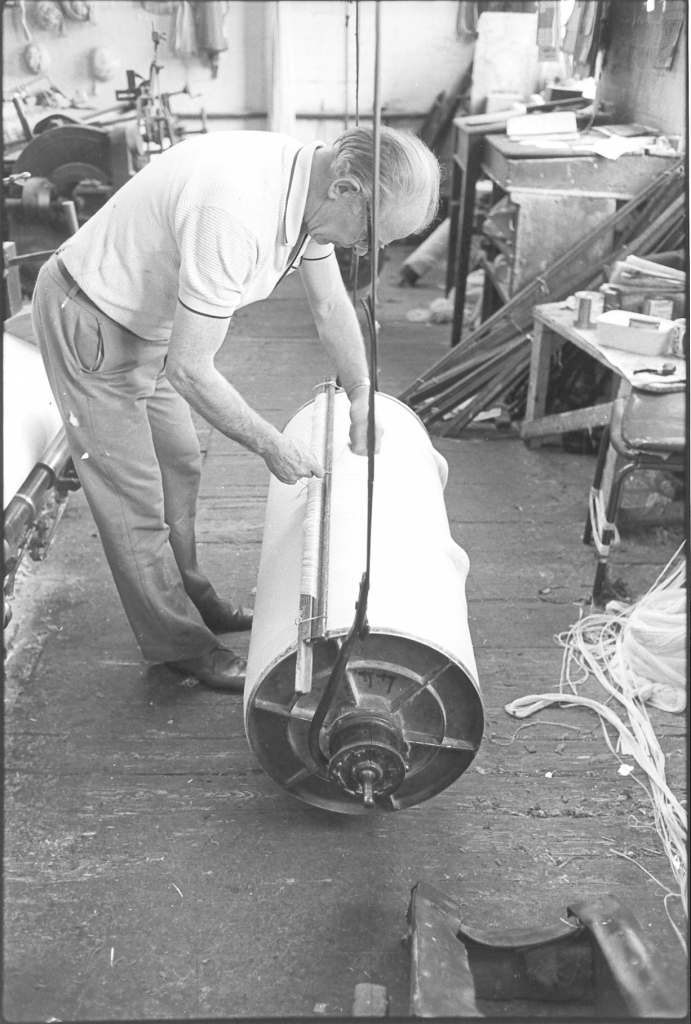

R- Well it’s on the squeeze roller. When it goes into the sow box, size box, and comes up it’s soaked with mixing, it’d he running of it but it has to go. There’s an iron roller at the bottom and then there’s your squeeze roller on top to squeeze the surplus size out. If you forget to put your roller down and start off you have size running out at the front of the tape.

Aye. I’ve seen that happen some number of times at Bancroft I’ll tell you. Running through the floor boards into the warehouse.

R- Aye, they’ve forgotten to put the roller down.

And it's the slippiest staff there is.

R- And sticks you to the floor!

Aye. And after it’s been there, that’s another thing that always struck me about size is that after a time, I don’t think I know anything that smells worse than old size.

R- Sour.

Than sour size.

R- Aye. But sago [didn’t do that] it’s tallow. We never had sago much, we used cornflour. But it’s very harsh is that, it wears the healds out does cornflour, it’s sharp. [Cornflour is maize flour] You can boil it and boil it and boil it but it doesn’t lose that sharpness. But for sago, to be done right, and not many taper’s will how to do it, it’s to boil 160 or 180 minutes. It has to boil sago flour to get it smooth. And if it isn’t smooth it’s wearing healds out. You can tell whether the taper’s mixing his size right or he isn’t if there’s a lot of healds wearing out.

Yes, well that were one thing at Bancroft, we did use some farina but I’ve been thinking as you’ve been talking, we did use a lot of sago flour and all. And I know Joe used to boil… they used to boil it and boil it and boil it, and of course I used to play hell because we had to make the steam for it.

(850)

R- Yes, for 160 minutes. But farina, if you boil it more than 10 minutes it’s gone to water so if you’re boiling farina, potato flour, and you forget it, you’ve a beck full of water if it’s done for more than 10 minutes.

Aye. Well, at the latter end we were on sage flour.

R- Yes. Well you’d have to be for Johnsons, you were doing [weaving] for Johnsons.

Yes, we were on sago flour and tallow. And I know that, give them their due at Bancroft, that was one thing at latter end which they did, they got the best sago flour they could afford, and they got the best tallow. That tallow we used to get were beautiful stuff, you could have put it in a chip pan.

R- Were it in big wood barrels from Australia?

No it was in small cardboard boxes. It came in cardboard boxes like dripping does to a chip shop. And I know that it took Jim Pollard, Jim went on to ‘em for ages because instead of buying [good tallow] they used to use that substitute stuff in 45 gallon: drums and it was terrible.

R- Oh what the hell did they call it. They tried it with us. Aye. It was supposed to be better, it were damned useless, aye it were useless.

Aye. It were horrible and it stunk terrible .

R- You forget these names when you’ve been out a bit.

Yes, but tallow, I know they hardly used any of this tallow, they hardly had to use any with the sago.

R- Well no.

Whereas the other stuff, they were shovelling it in and shovelling it in.

R- It were a pound to ten, one pound of tallow to ten pounds of sago and you mixed… We’d nothing else here except when you got on to spun silk. Soft soap. But the best thing for spun silk is Gum Tragon as well as sago. You see there is no dusting off when you use Tragon. I remarked to you what a dirty place Bancroft was, well if they’d been using a bit of Gum in it there’d have been no dusting off.

Aye.

R- But I were doing that at Johnsons and it wouldn’t finish right. It weren’t pure enough for bandages, they couldn’t get it out, Gum Tragon, as easy as they could sago. They were always complaining about it, they couldn't finish it.

Aye. ‘Cause of course bandages, after they were made, they’d to be washed out, it’d all to be cleaned out wouldn’t it.

(900)

(40 min)

R- Yes. Oh it had to be [clean]. And they’d the chemists you see, to see whether they were pure or not.

Aye. In a lot of ways, that was always a laugh down there. I know one of the things that I’ve heard Jim say about Johnsons. How it’s run at the moment. He said “Their trouble is they spend too much time worrying about tensile strength of cotton and the tensile strength means nothing. You can have cotton that’s twice the tensile strength of another cotton, but the cotton that’s weakest will weave best, and that’s what they couldn’t understand.”

R- No. But why Johnsons are always on about the strength of cotton is because they’re weaving such a lot without any mixing on at all. That’s why it’s tensile strength they want.

Yes, but they, I know that Jim said they were having terrible trouble and in fact they sent for him at one time after Harry had finished, Harry Crabtree that is. And he said that was all the trouble. He said their trouble was that it was somebody down in Wrexham that was buying the twist.

R- That’s it.

He said all he was doing is buying it on tensile strength and how much it costs. And he expected them to weave it. Well, Jim said you can’t run a Lancashire weaving shed off that.

R- Well, when Lowe and Chris Taylor and Allan Smith were here, now it were run were this place, and it were run properly. Everybody had a job, you weren’t pushed and if you did your job there were nobody said a word. But after Taylor and Low left it were just like a ship without helm, they got a chap .. I don’t know where he were from. He come from Manchester, a chap called Abbot, he has a pet shop in Barlick now. Jack Abbot, you know him? He lived down Gill Lane somewhere, at a dog kennels. Well he came, he hadn't a clue. However he got in I don’t know, he must have been able to talk, but he hadn’t really a clue.

Did he go as a manager?

R- Aye he come after Lowe finished, he come as manager here. He might have been all right from the office side but he’d no practical experience at all, just none at all.

I think part of the trouble with him, what was his name, Ironside is it.

R- Ironside were another straight out of the army. Well, they got shut of Abbot here and sent him to Gargrave. Well, he’d that place wrong side up at Gargrave, he got stopped. And then they got another chap, no idea, lived

(950)

up at Thornton, then they got Ironside, and he’s gone as an export manager now down at Slough or Portsmouth. But they must have influence, it isn’t their ability that gets them in. And they’ve a fellow now that’s come from TAC at Colne. He were at Smith & Nephew’s and then he were at, there's a place called TAC at Colne isn’t there. I don’t know what the initials stand for. Johnsons taped a lot for them at one time.

Who. TAC?

R- Yes. Johnsons taped a lot for them at one time. It were gauze stuff and now he’s come here. Eh, it’s Mac something, McGuiness that’s manager now. And Ironside moved on and they got somebody called Clancy. And they brought him round see to see how much he knew. They took him into the twisting room, and there were a twister there and he were saying, the chap that was in, “These are healds and this is the reed and this is the warp and what he had to do is pull these ends through.” And that’s Clancy, he’s over Johnsons here, over the lot of them now.

I’ll have to put in for a job there.

R- Yes. And when Abbott were there, they moved from down there into another part of Brook Shed.

Yes.

R- And he had them setting looms out did Abbott. Telling ‘em to put so many in, and they had to be in eights. And he had them putting all the handles into the alley. Out at the end, farthest point away instead…

Aye, that’s it.

R- Aye, he had his fours in the middle and then t’other two like the others, he’d send the handles out into the alley. And they were letting him do it were the tacklers, and a silly bloody tackler went and told him what he were doing, That’s the sort of carry on.

And he didn't realise that the whole idea was to get all the handles as near to the weaver as you can and then it made less walking about?

R- Aye. Yes, but they were all, all pounds out of ten, bloody hell. Oh, there’s been some right misdoes here. But Johnsons, they’re all right Johnsons themselves. I’ve nothing to say about them, they’re a good firm. Always been good to work for. But as I say when Chris Taylor, Lowe and Alan Smith, they did the buying, now the place were run [right]. Nobody wore pushed, always work going on and plenty of perks. And superannuation for ordinary common or garden workers as it were, something unknown.

Aye, especially in the weaving industry.

R- That’s what I mean, in weaving. And weft men and warehouse men and everybody, didn’t know who they were. It didn’t matter who they were* and it’s just made t’difference between, for me like I’d have been in the workhouse or been able to manage comfortably.

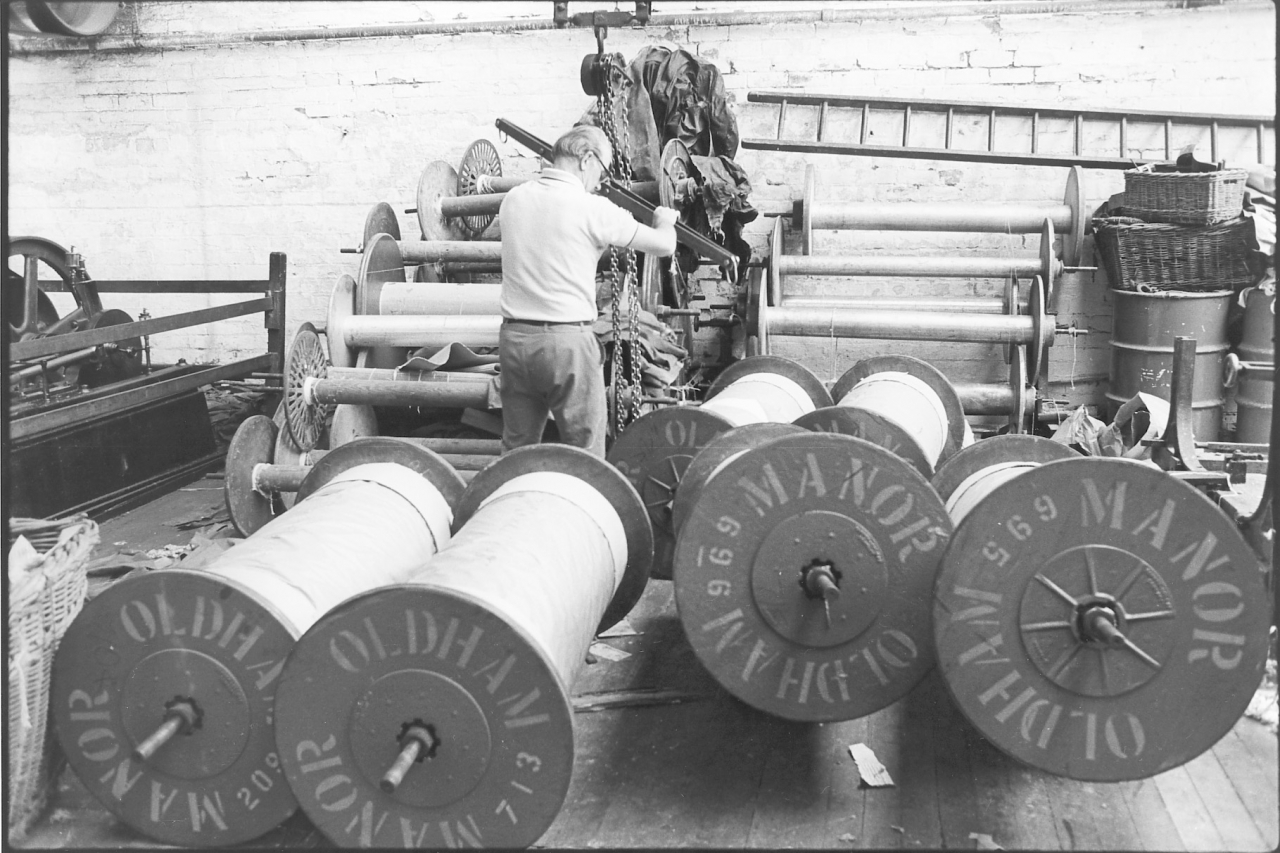

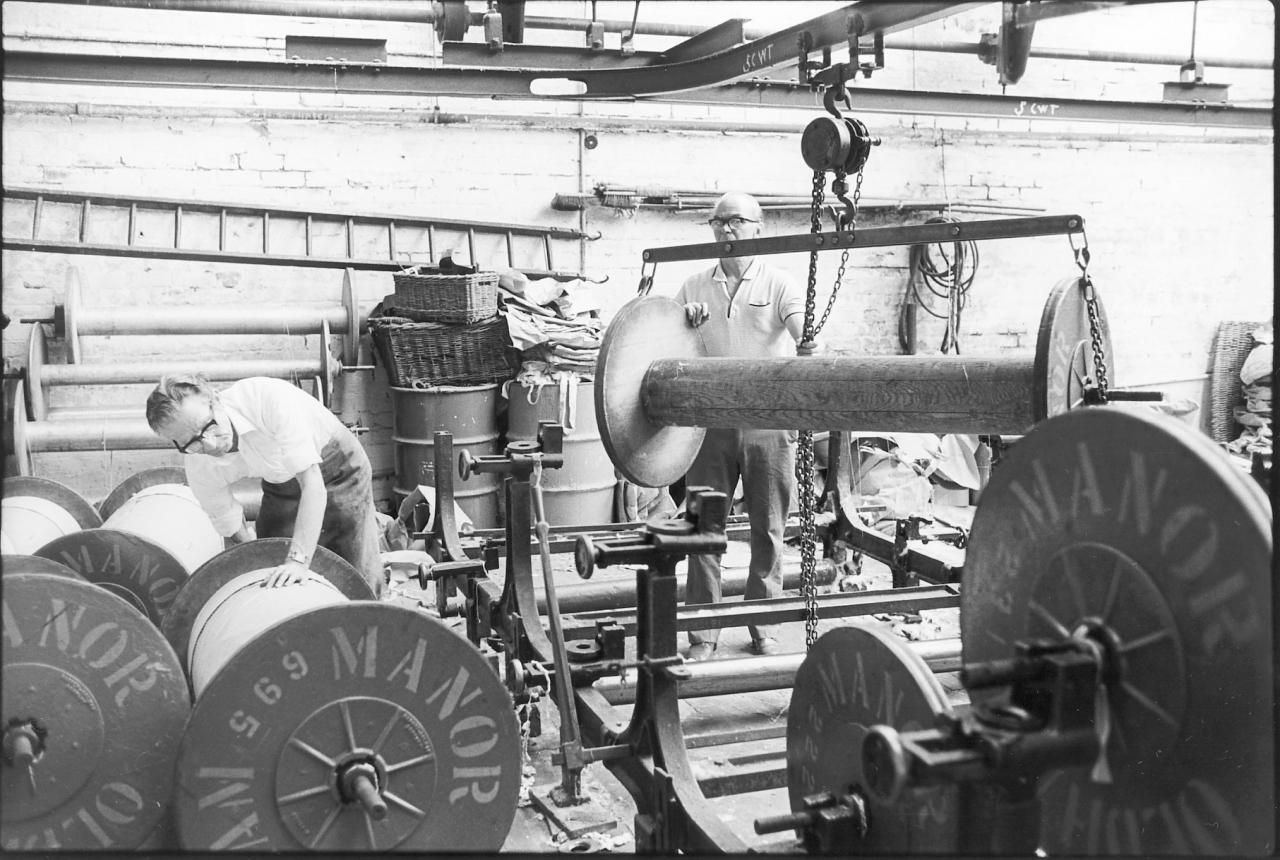

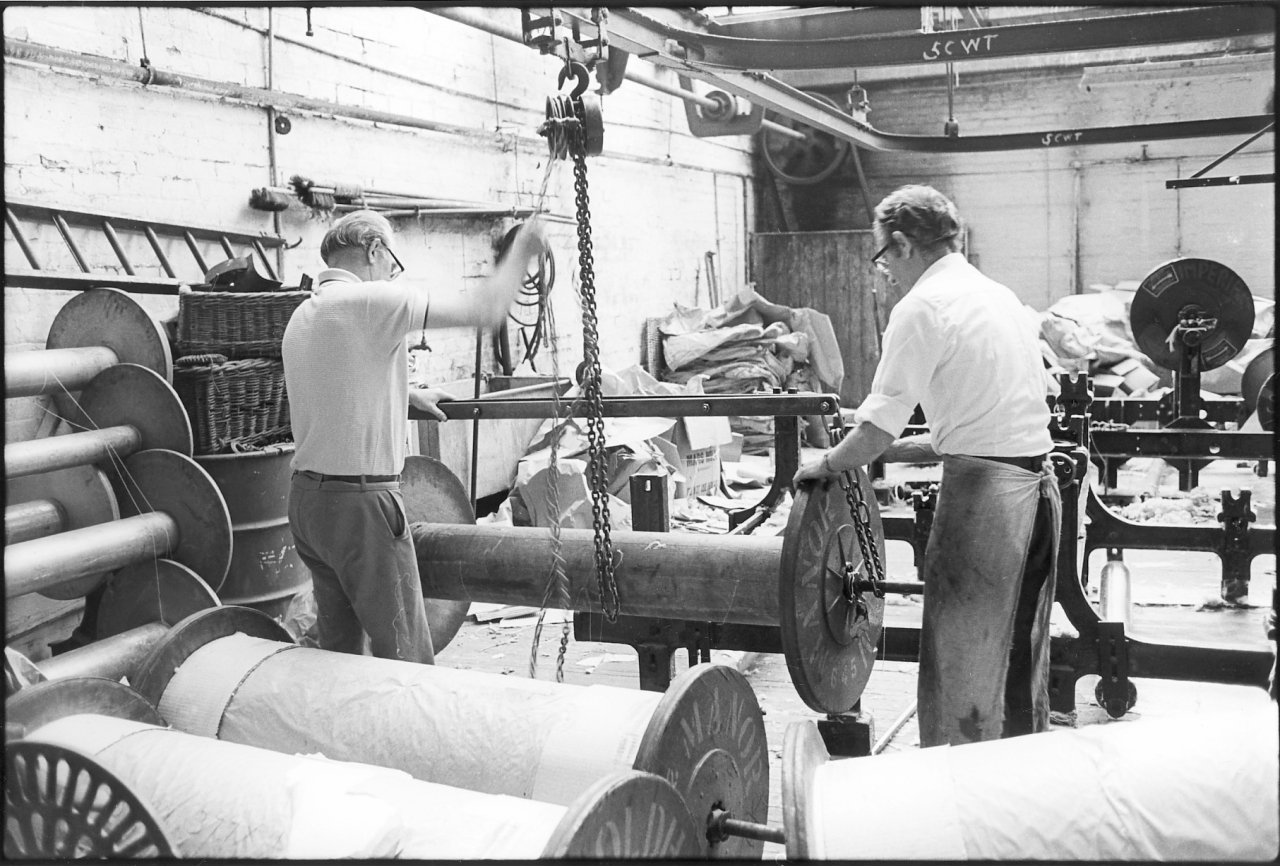

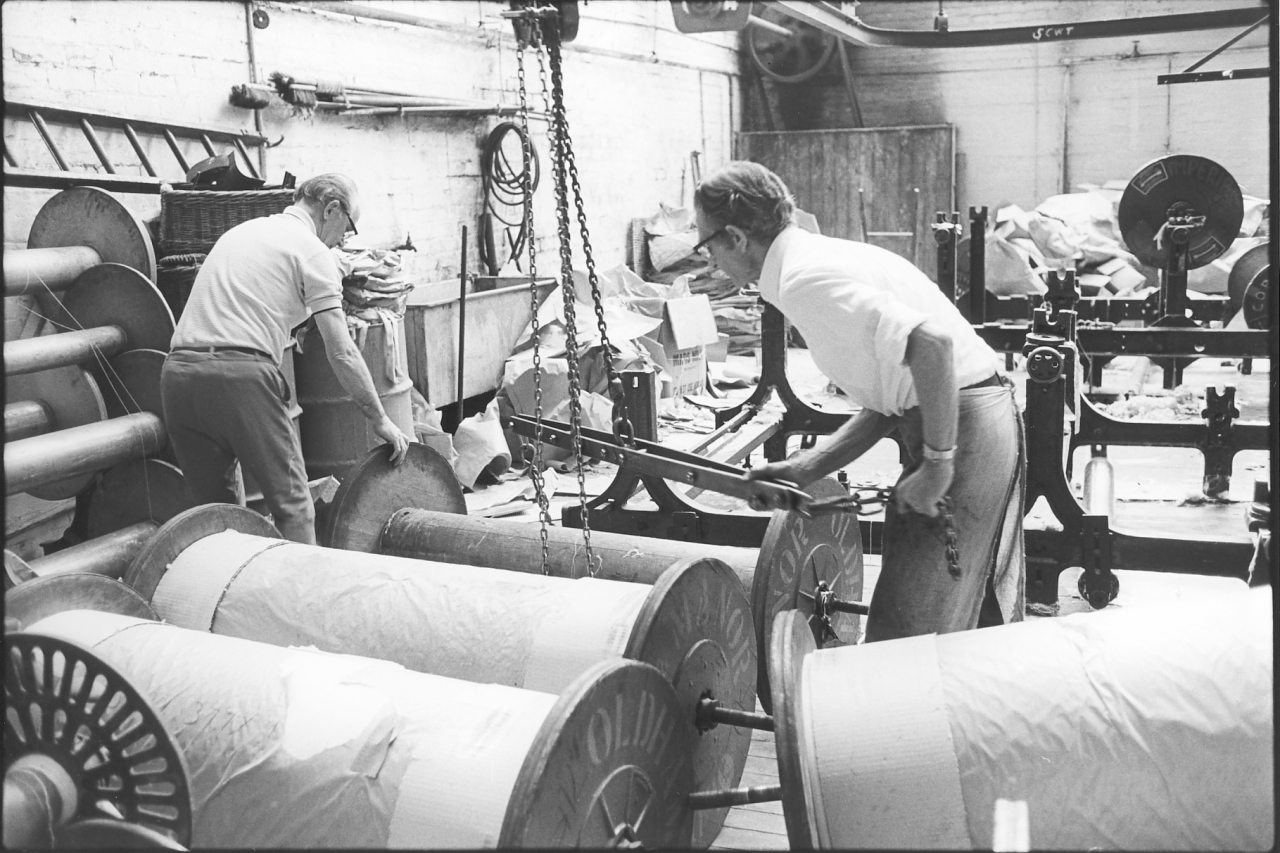

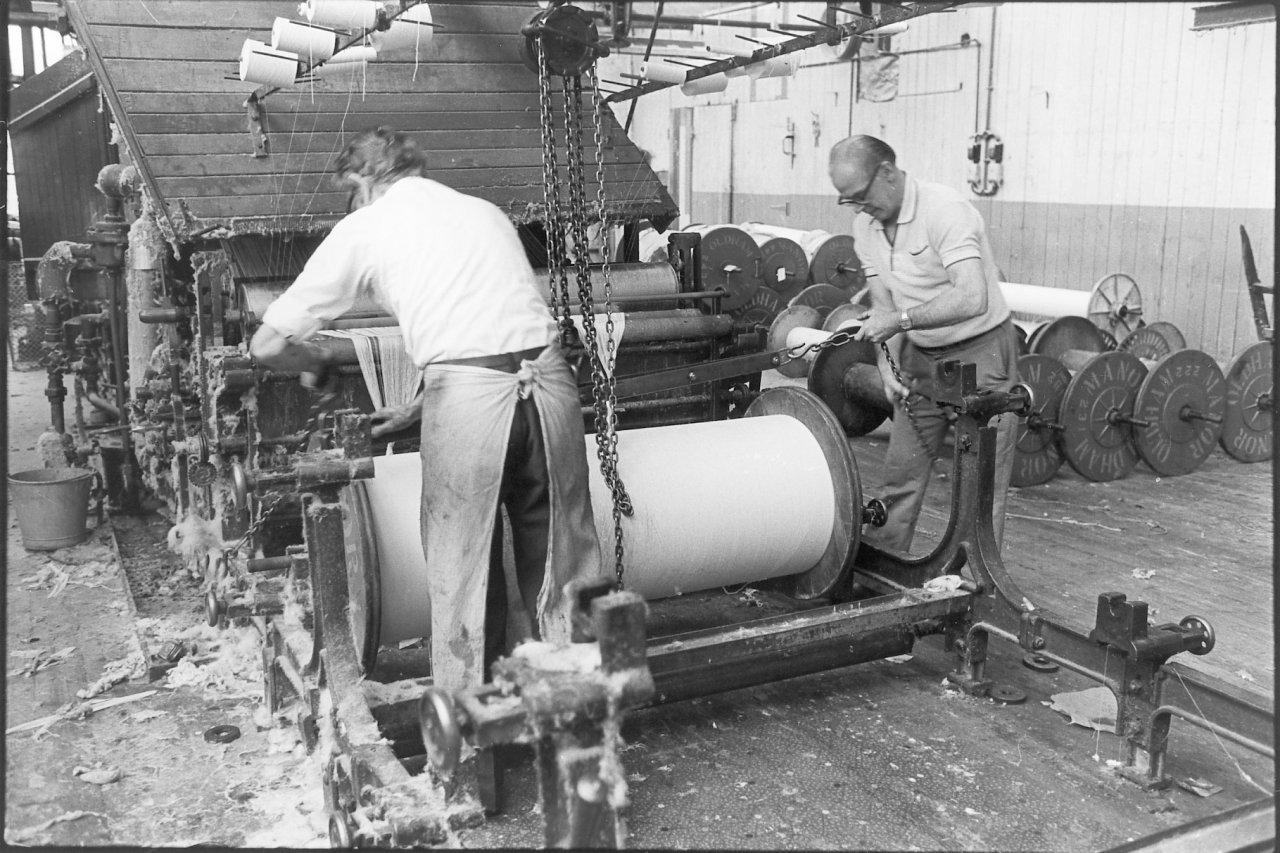

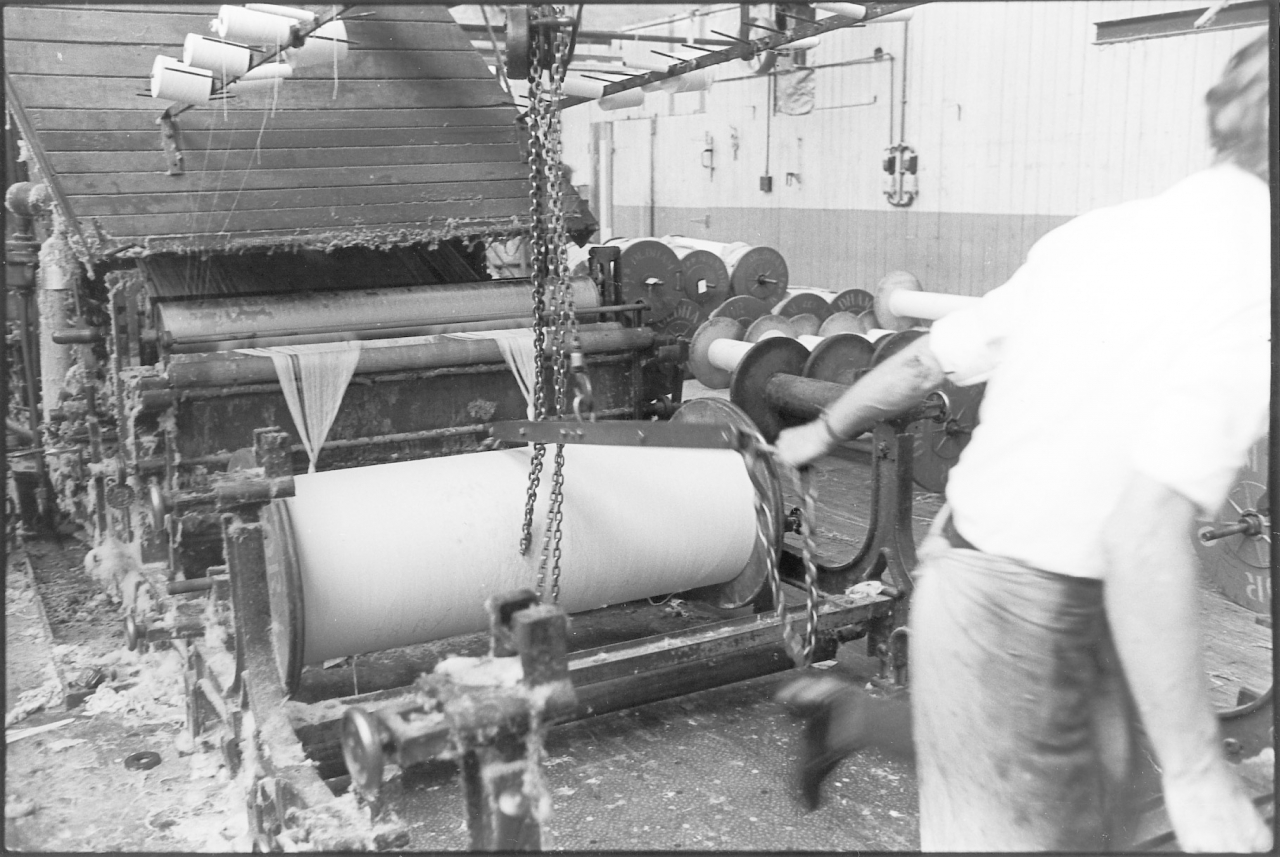

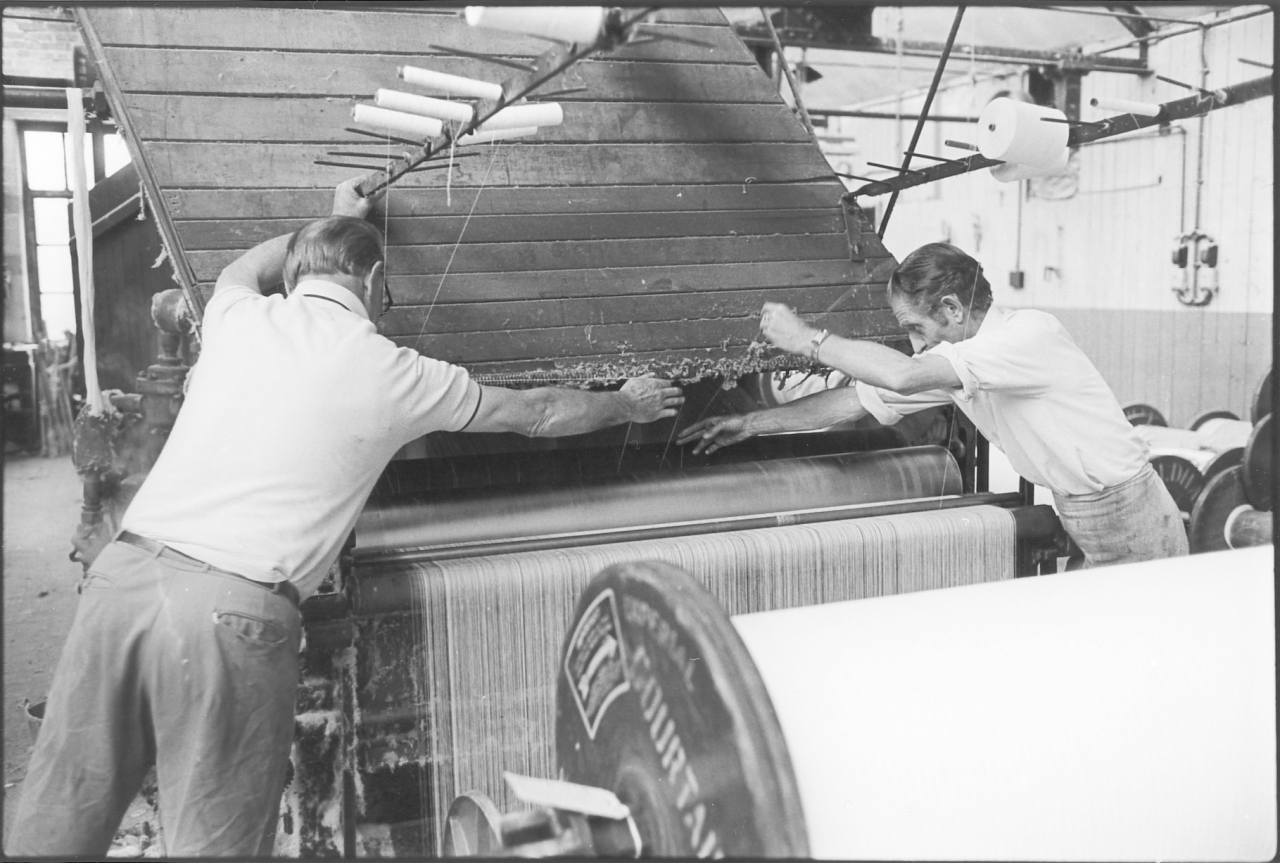

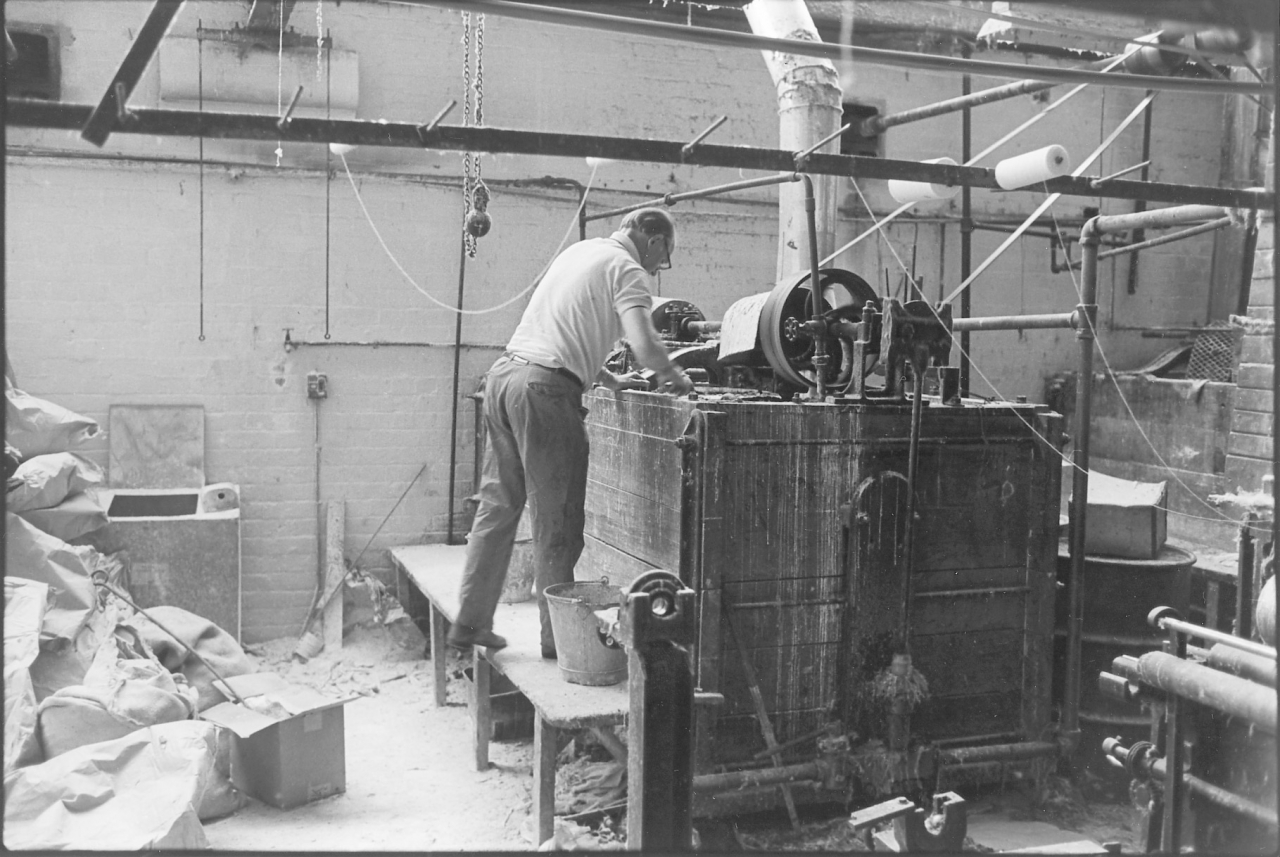

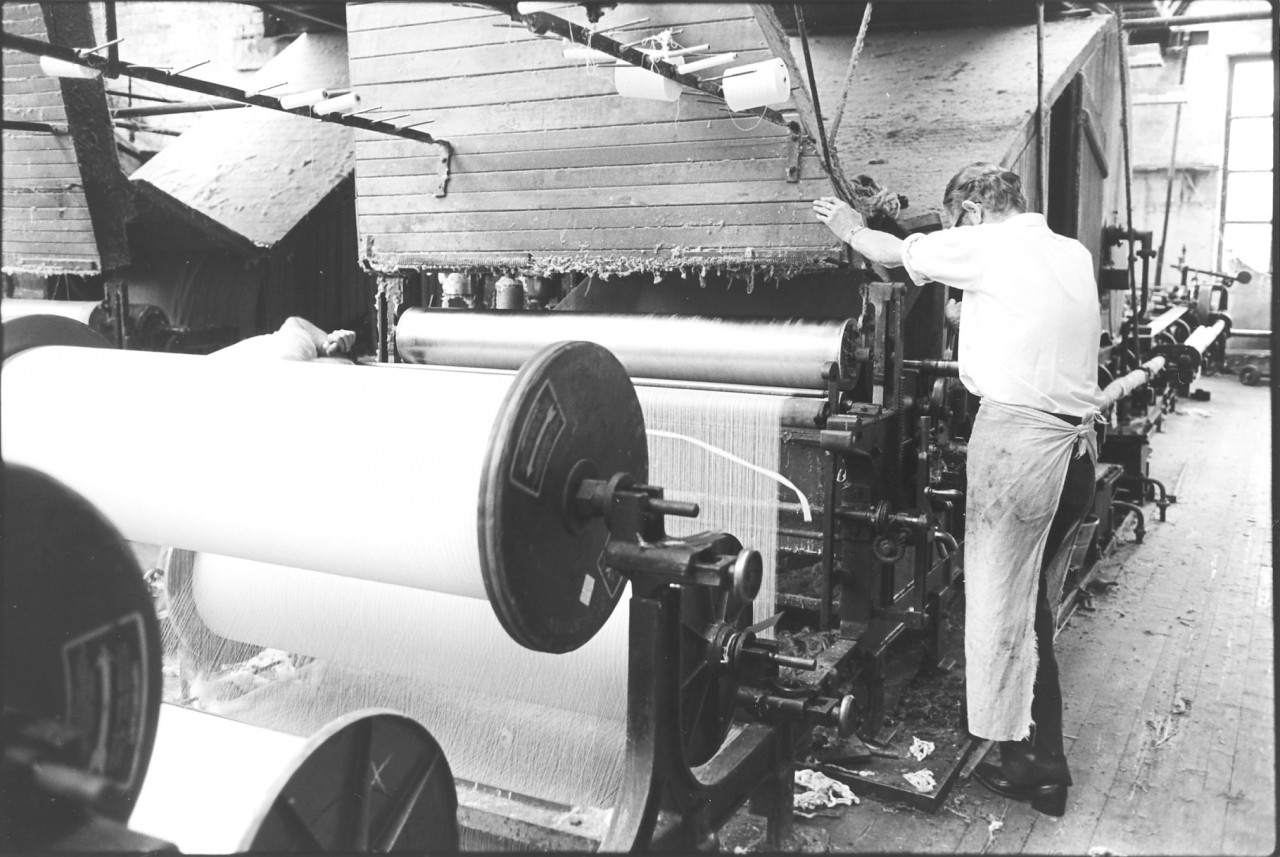

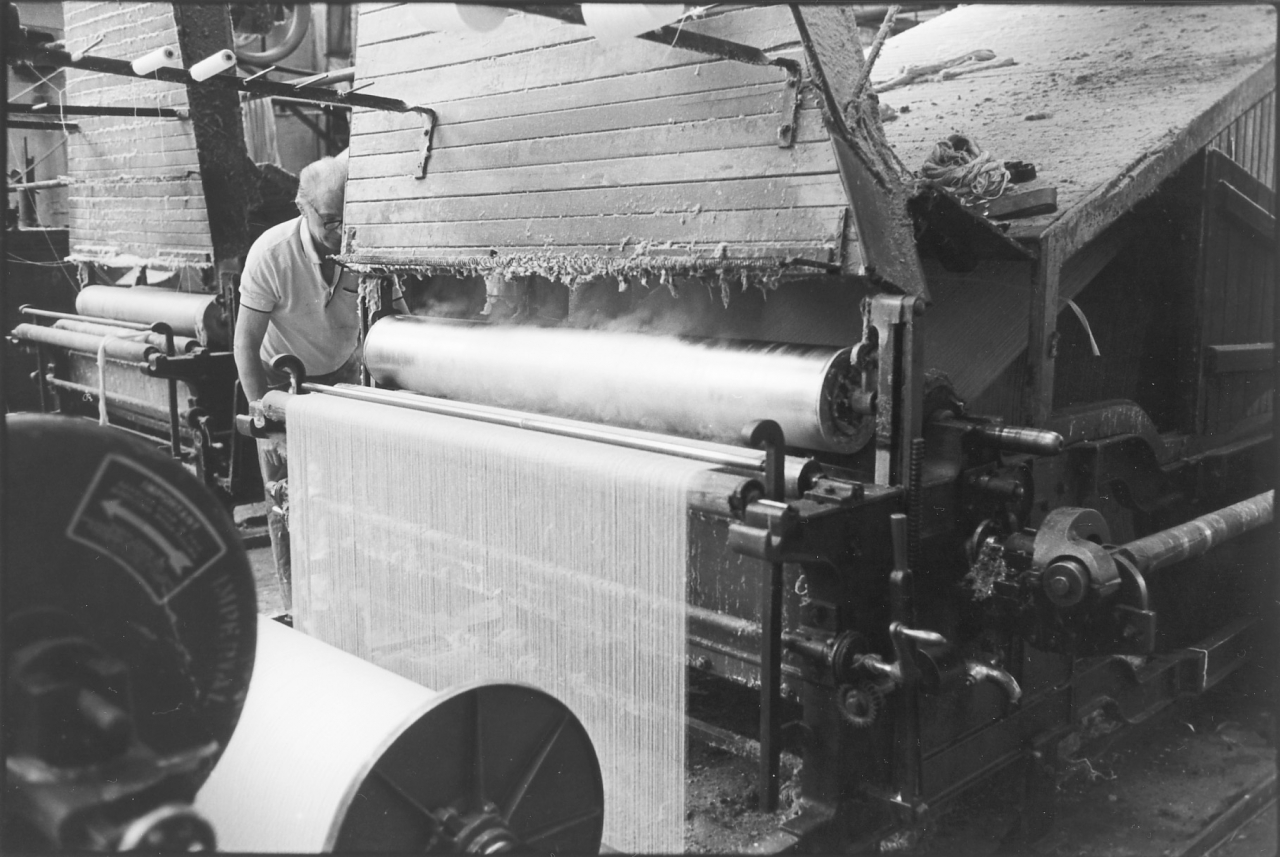

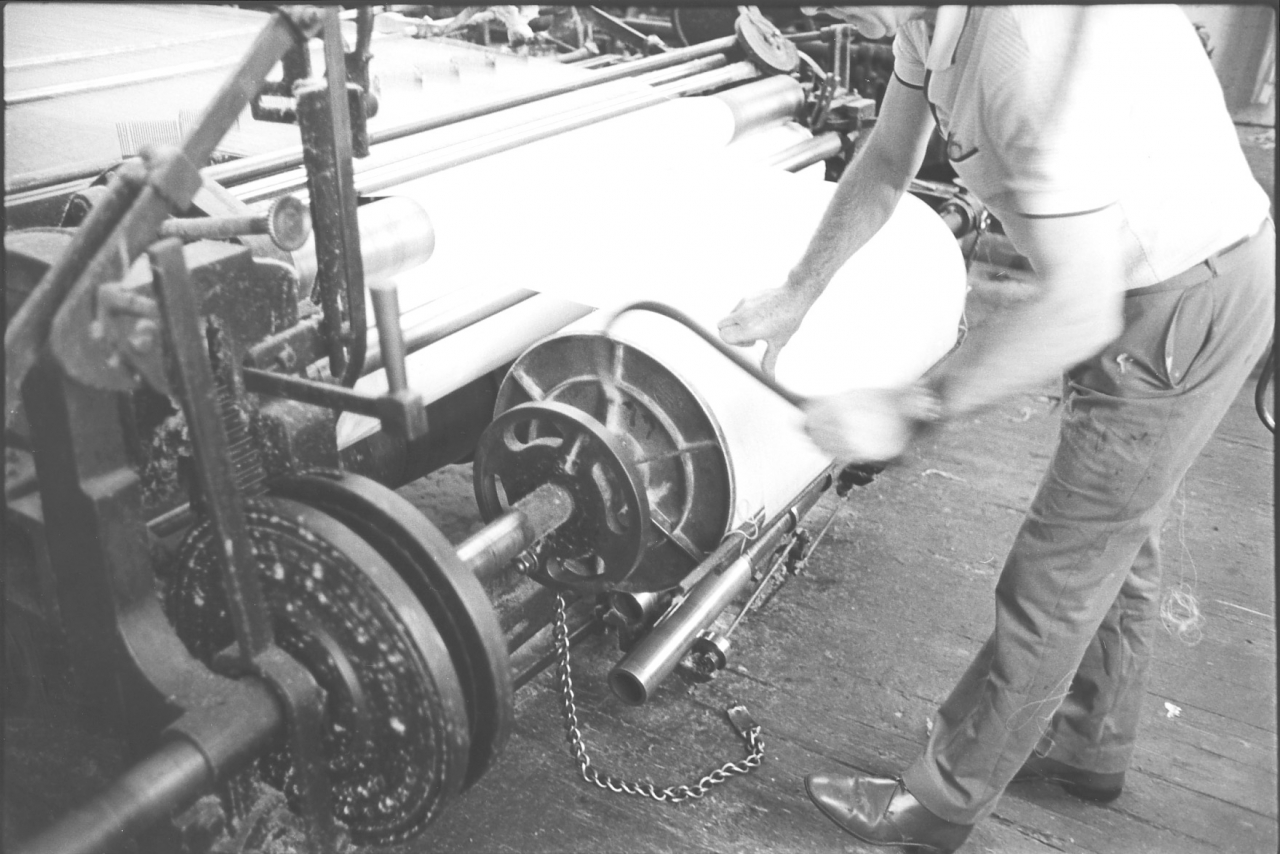

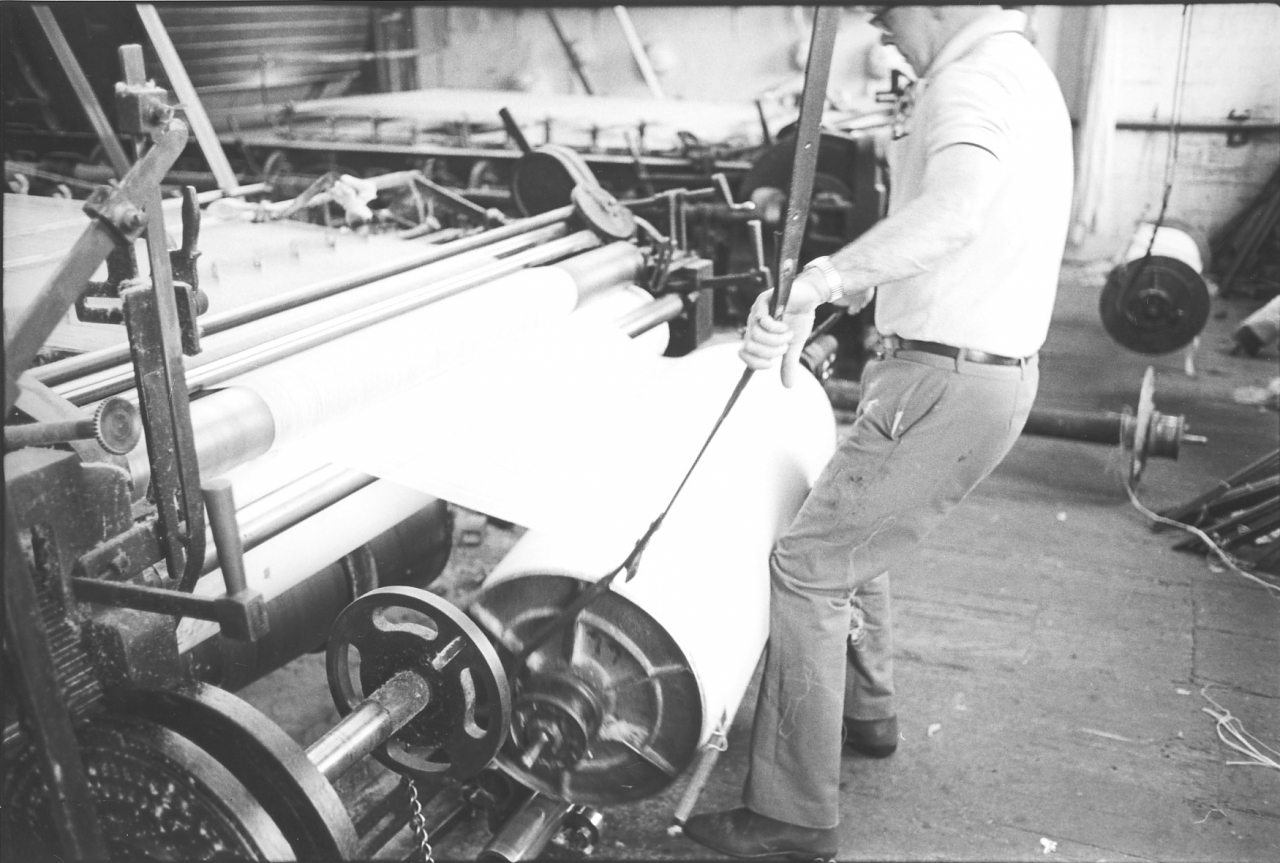

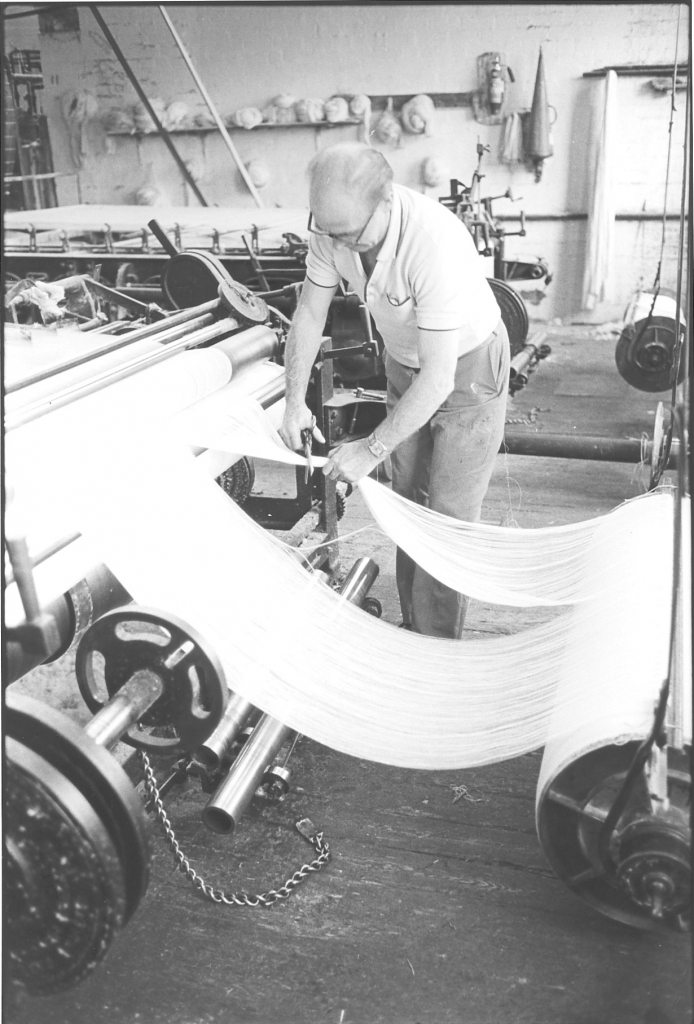

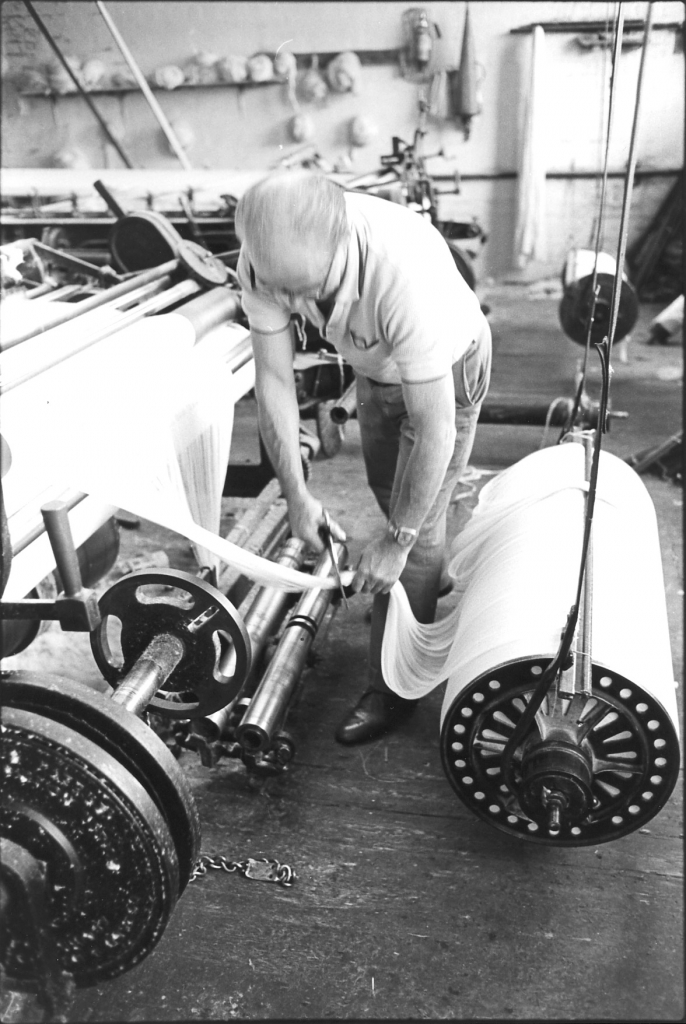

Well, we’re getting near the end of this tape now Horace so I think what we’ll do we’ll leave this now. Now next tape we do, we’ll get round to running through the pictures. And I think that’s the way we’ll get all we want out of taping. That way, because as we are going through them all sorts of other thing’s will crop up. We’ve to go through them reight slow and I’ll get you to describe everything that Jim Nutter’s doing on those pictures and any comments you’ve got to make about them while we are going on. That’ll start to give us a fairly complete picture of taping. So we’ll leave this now until we go on to the photographs.

SCG/15 March 2003

7,010 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 79/AD/11

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 17TH OF JULY 1979 AT 16 COWGILL STREET, EARBY. THE INFORMANT IS HORACE THORNTON, TAPER AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Right Horace, bits and pieces tape first today. What I want to do is just catch one or two loose ends together that we’ve had up to now before we actually get on to the photographs. Now I've got it worked out straight in me own mind now .. You were working at Rycrofts at Broughton Road at Skipton and Billy Lancaster, young Billy was running the engine there and old Billy was running the engine at the Big Mill.

R - Yes.

Now, with you knowing Billy, when he moved down to the Big Mill you took the opportunity of going working with him as oiler and maintenance man down there so that you could he nearer home. So you'd be working on the engine at Big Mill, at Victoria Mill, from 1945 till about 1947 and then you left them and went working for…

R - Johnsons.

Johnsons. Now then, there's one or two things in particular that I'd like to know a bit more about, about working on the engine. Now, first thing is…

(50)

actually you’d be employed, you wouldn't be employed by the people who had the looms in the mill, you'd be employed by somebody else wouldn't you. And you tell me, who was employing you?

R- Proctor and Proctor, Grimshaw Street, Burnley, they were the men in charge. There were various mill companies all up and down Lancashire, and Proctor and Proctors, they were chartered accountants, and Teddy Wood were a mechanical engineer with string of letters after his name and he looked after the mills for them you see, New Road, Victoria Mill, and mills all up and down in Lancashire, I don’t know how many. But Captain Smith that lived up at Thornton and a Mr Jacques his brother in law owned the Victoria Mill.

Yes. Now would that be, am I right in thinking that was the Earby Shed Company?

Earby Shed Company were Broughton Shed here. [This is wrong of course. I think what Horace meant was Brook Shed on New Road and this was a slip of the tongue. ESC certainly owned Brook Shed. I think that the name that Smith and Jacques traded under was ‘The Mill Company. Shed occupancy is relatively easy to ascertain via the Manchester Exchange Directories but shed ownership can be a difficult matter.]

Aye. And I think that they owned Sough and all didn’t they?

R- Yes, that were Earby Shed Company. I don’t know who the shareholders were but Teddy Wood ran it for them and Proctor and Proctor, accountants, they ran it, paid the bills and let it to tenants and fixed the price the tenants had to pay. Who the shareholders were, nobody knew.

In other words, they acted as, where an estate would have an estate agent, they’d be agents for the actual mill owners.

R- Yes, and if any jobs wanted doing, Johnny Pickles got the job.

(100)

Yes, that’s it, aye. So you were working [at Big Mill], what exactly was your job with them during that two years you were working with Billy Lancaster?

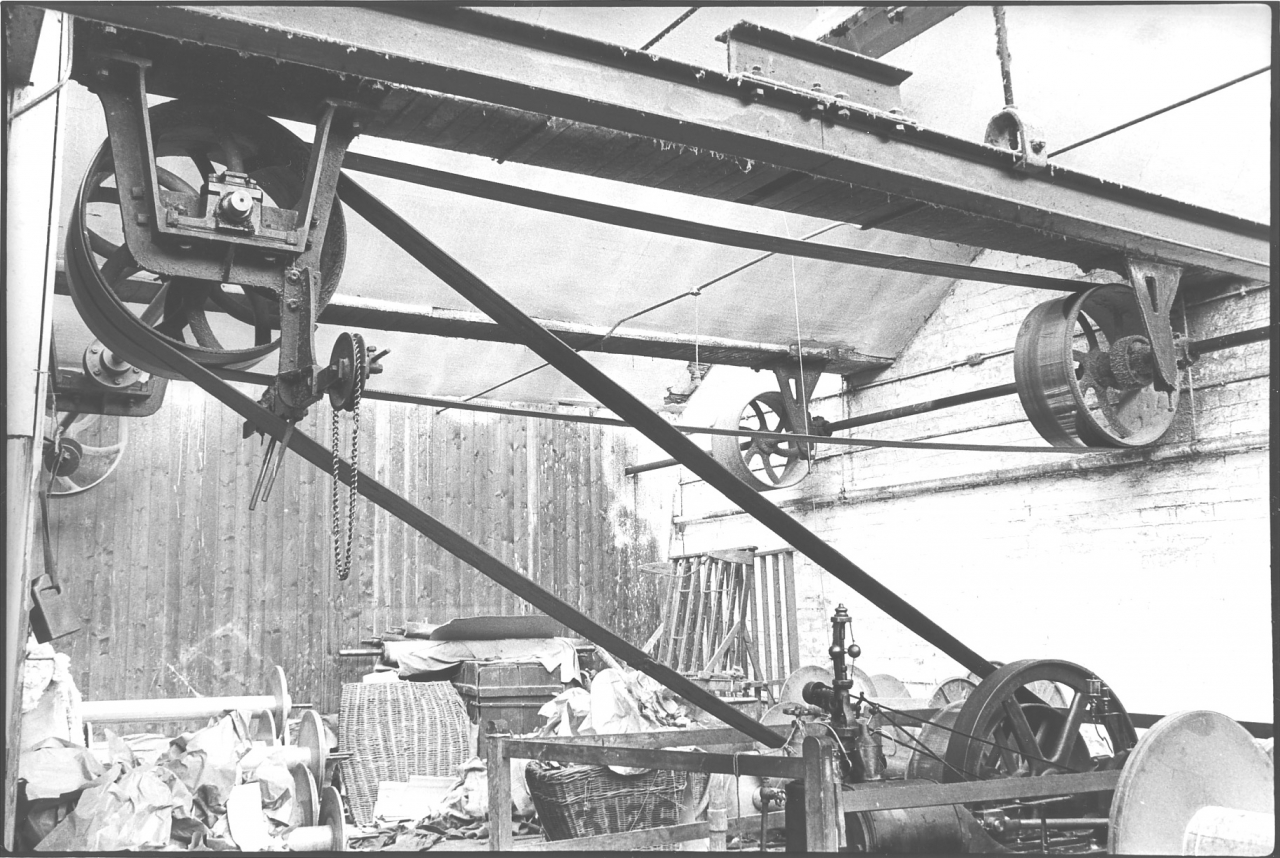

R- Well, we’d to be there, ordinary times, half an hour before starting time. The boiler man would be there at the same time. And you oiled round, saw that everything were filled with oil. Started the donkey engine up because you had to bar it round [the engine] for half an hour, you’d to get all the bearings moving, there were such an amount of shafting the engine wouldn’t start it on it’s own without this. Especially in cold weather when everything were stiff. [Cold grease in the shafting bearings. Victoria Mill was a peculiar layout, it was vary long in relation to its size and had a greater proportion of shafting to space than most other mills.] So you barred the engine round for half an hour and it would start then would the engine but not without you barred it round. That were the procedure, morning, dinner time, breakfast time, three times a day you’d to bar up. And usually, when you’d got running, everything going all right, you’d lots of jobs you’d

(5 min)

to do round about the mill, or you went round, my half, went round to see all the bottles were filled and there were no hot bearings or anything. [Evidently Horace was responsible for half the mill and the bottles he refers to are the oil bottles that dripped oil into the main shaft bearings. The individual line shafts that carried the pulleys for the looms relied on grease pads in the bearings.] In Winter time, go into the boiler house and help the fire man, bad coal, clean a fire or two out for him. [Heavy firing, especially with bad coal, meant a lot of ash and clinker in the boiler furnaces and this had to be cleaned out to maintain heat transfer. Victoria Mill was under-boilered and they were always pressed hard but even more so in winter with the additional load of the steam heating in the sheds.] Any jobs there were, but usually in Summer time when you weren’t steaming the mill and everything were going

(160)

all right, well .. you sat out on the bridge for hours on end. I mean, it was quite a comfortable job. Just a quick look round to see to it the engine were all right. But usually you’d some jobs to do, putting windows in and such things as that, and jobs, general maintenance. Winter time you did turn and turn about. If it wasn’t too cold you came at three or four o’clock at the morning, get the steam round, Sunday night came at midnight, steam [the mill] and get everything warm. See, they were getting fairly strict then, it’s supposed to be 55 degrees [Fahrenheit] for the start. And go round the shed and look at the thermometers at dead of night, and that’s all you did.

[What Horace is describing is the common routine in all the local weaving sheds. The North light roofs allowed rapid heat loss. The sheds were heated by steam at full boiler pressure in two inch diameter iron pipes suspended in the roof space about nine feet above floor level. This is of course the worst place to put the pipes in terms of efficient heating but was done like this because if the warps were subjected to anything other than gentle indirect heat, they would dry out and give trouble when weaving. The consequence was that the air in the roof space next to the windows, the coldest place in the shed, had to be warmed before any effect could be felt at floor level. I have seen the temperature fall at floor level as the steam went in many a time when warming the shed. This was because the rising warm air was forcing the cold air from the roof down on to the floor. Very disheartening! Note Horace’s reference to ‘dead of night’, there was no light apart from what you carried and the shed could be an eerie place. You were never more alone.]

What were it like warming it up? Was it as bad as it usually was?

R- Well you can imagine, they were like greenhouses and there were only steam pipes wandering back and forwards, well .. it just went straight up at that place, and straight through the glass. Johnsons had a lot of fans, fixed on the steam pipe to distribute the heat, and that did all right. And then we doubled up with steam pipes, we seemed to he putting miles of steam pipe in extra because of what they’d done for the workers before the war wouldn’t do after, there were all these regulations about a certain degree

(200)

of warmth and working all week ends. And then part of the Big Side had been used for storing ammunition during the war. [They closed] a number of looms down and the work people had to go into munitions. And the warehouse and parts of the shed were empty in some cases, probably had been empty for, well, I don’t know, twenty years. And then after the war, when there were a bit of a boom, every place were taken. There were the New Bridge Weaving Company [Newbridge Mill Ltd. Lower Clough Mill, Barrowford. P A Fewster mill manager. Source Lancashire Textile Industry, 1941.] they took a shed here, so many looms, a couple of hundred or something like that. And he were a chap that didn't really know what he wanted. We spent all week end moving pulleys, moving looms and moving pulleys and he couldn’t be satisfied where he wanted them. Because I know my mate told him straight once, he said “Tell you what you want Mr Fewster, you ought to get all your looms on castors!” Aye he did.

What was his name, that fellow?

R - Fewster.

Just one thing that strikes me there .. I think Fred Inman worked for him at one time.

R- He did, Fred Inman worked for him. I think he came from Birley’s to work for Newbridge. That’s where I first come in contact with Fred, good tackler were Fred, very patient, didn’t lose his temper. Oh no, he was a good man were Fred.

Yes, he still is.

R- But it were funny were that. He didn’t take offence, but he didn’t do as much of it. You know, every week end that come moving looms and moving pulleys on the shafting.

(250)

(10 min)

Aye. Something that I should have asked you about before, you’ve triggered me off there, as I said, this is going to be a bits and pieces tape. You’d worked in textile mills right the way from the end of the 1918 war, the 14/18 war, up to [the present day] and now we’ve got to the stage where it’s after the second world war. During the second world war, how did things change in the mill? Were there any changes? Now obviously we are talking now about your experience at Broughton Road. How did things change? Did you notice any changes in the way the mill was run and the way the workers were treated? Could they be attributed to the war? Shortage of labour and such?

R- I don’t think so, it were a gradual change. More regulations came in and the guaranteed week. They hadn't to be sending you home if you’d only two looms you see. It was that they’d to pay them a guaranteed wage, that were the best thing that ever happened. And then holidays with pay come in, there’d never been anything like that before, you were feeling a bit more secure. And then the Beveridge report came out during the war to keep people working on the war effort you see, think of the promised land when the war is won and over. It were a gradual change. When they put in for holidays with pay we just used to think it’ll never happen, never happen in the cotton. And then when it got to a fortnight, well it was unbelievable.

(300)

That’s a fortnight’s holiday with pay?

R- Yes, with pay, yes. And a guaranteed week and that were the most wonderful thing. Weaving had always been hit and miss job, had been for years. Like, all my experience there were firms all round you going bankrupt and you did use to long to get a job that you were certain of a wage every week. Now when Bill Lancaster asked me to come here it were that guaranteed week that persuaded me to come here apart from other things like being at home and more wage than what I were getting at Skipton. But .. guaranteed wage whether you were…holidays or what it were, bags of overtime.

While we’re talking about wages, now what was your wage when you come away from Broughton Road?

R- About £3-15-0 a week.

That’s £3-15-0? [£3.75]

R- Yes. And if I could have got away, you see [I was in ] a reserved occupation, if I could have got away I wouldn’t have cared whether it had been into the army or what it were. But having to go down there and work for next to nothing. I could have started at Rolls and they were coming out with £10, £15, £20 a week.

Even in those days. Now when you came down to Earby as oiler on the engine, what was the rate there?

R- £5 straight off, for a bare week..

Would you say that, in general, people in reserved occupations, the management knew that they more or less had them by the short hairs. Were they worse paid than people that weren’t reserved?

R- Yes. A man that were over military age, he could demand anything if he missed being directed to a certain job. But otherwise you were stuck there, there were no overtime, no nothing, just a bare wage and you couldn’t get away, you couldn’t do anything.

(350)

(15 min)

Now tell me, did the conditions apply during the war? When did this change? Before the war, in weaving, they were paid purely on piece work, they were paid on so much a piece and the number of pieces they got off in the week.

R - Yes.

Now then, obviously under that system it was possible, if you hadn’t many looms running and you were on bad warps and you were unlucky it was possible to work all week and perhaps only get one piece off, perhaps only get six bob for a week’s work. When did that change?

R- When the guaranteed wage come in.

Yes, when was that.

R- I can’t really tell you what year it was but it were after the war. Well it might have been during the war, I can’t just remember. But down at Skipton a man had four looms and his wife were working at the side of him and they’d only three loom apiece or two loom apiece. They wouldn’t let the wife go sign on and the husband run the four looms, that were the conditions before the war started. They made them come to their work and you couldn’t sign on.

Would you say that the sort of scales of pay and the conditions we are talking about were worse in the textile industry than they were in other industries?

R- Worse than any industry because where you get predominantly female labour they can do anything with them.

Do you think that was one of the reasons?

R- Weavers are never on strike, “Oh we are all right. Oh It’s all right. There is plenty.” That’s why wages are poor.

(400)

Do you mean, what you’re saying, really, is that part of the troubles of weaving, the fact that weaving’s never been regarded as a skilled job and it’s never been a highly paid job is the fact that there were so many married women weavers who [had their husband’s wage to fall back on]

R- Yes.

Who more or less regarded weaving as a way of earning extra money rather than the basic wage.

R- In a cotton town there were mill work or shop work or servants, there were nothing else. And the bosses usually owned the factories and owned the land all around. No one else could come and start up a do, any different to weaving.

Aye, that’s interesting. Now that’s an interesting point, yes.

R- They couldn’t start another industry where there were cheap labour, because they couldn't get land to build, they couldn’t rent anything. And Armoride started down there, you know where they are? Grove?

Aye, Grove. [Grove Mill at Earby]

R- And, they wanted to move from Idle, I think it were Bradford way they were at. Before the war when there were such a lot of unemployed at Bradford, Armoride were such a poor paying shop there were always vacancies, and they gave anybody that were signing on the chance to go, but they weren’t forced to go. They didn’t stop their dole if they didn’t go because the wage rate were so poor. It were a Jewish firm and when they took the Grove there were people come over like our foreman and they told me, the people that’d been moved from Idle hereto, that it was the worse paid shop. And when they enquired for a place to move to they were given a list all round and square within reasonable distance of Bradford and Earby was the lowest wage place of any of the other places. What people were paid here. And there were another flaw, there were another thing about weaving,

(450)

(20 min)

your wages were fixed from Manchester, you were paid on Manchester rate, and the bosses always said that Colne and round here were at a disadvantage because they’d more carriage to pay on the weft coming out of Lancashire and the goods going back. And wages were 5% less for weavers and everybody here than they were further on into Lancashire.

[‘Local Disadvantages Allowances: The prices set out in this List are subject to the respective deductions for local disadvantage in certain districts prescribed by the Award of the Industrial Court made under the provisions of the Industrial Courts Act, 1919 and dated the 28th day of April 1920.’ { Extract from the Uniform List of Prices. 1935} The Uniform list was agreed each year between the Cotton Spinners and Manufacturers Association and the Amalgamated Weavers Association and was the bible on which all wage rates were based.]

Yes, of course that was what they called Local Disadvantages.

R- Disadvantages.

And before the 1914/1918 war there were quite a few strikes about that weren’t there?

R- Well, they didn’t alter it, did they?

No.

R- It’ll still be going on, even though Rycrofts, their stuff nearly all went to Bradford. They had that 5% disadvantage. But if it’d been the other way about …

That's interesting, of course Rycrofts were cotton. And did they come under the same uniform list as you would if you were say, weaving fancies in Lancashire?

R- Lancashire, yes. And there were the fancy…

Because they consolidated the list didn’t they?

R- Yes they did, but it were after a long time. But anybody that worked at Rycrofts could work anywhere. If anything new come out, Rycrofts were in at it. New things, it wore a costly, costly business for them when they took silk up. Getting used to it, and I’ve seen out of 100 yards you’d throw 50 yards under the table. And it went on like that. But they gradually mastered it and got to be perfect in the stuff. Warps were anywhere when they were coming in. There were British Enkalon, it were a Dutch firm but it were called British Enkalon, they’d opened a place here and that were rough. There were viscose and acetate, but acetate were always the hardest and the harshest, more breaks in it than in cellulose, that were Celanese.

(500)

But they mastered it did Rycrofts, they were in at everything.

Was there any change in attitude .. 1 mean, let’s put it this way, before the war it was common to see tramp weavers waiting in the warehouse, and time keeping of course was strict in consequence, because if you weren’t there on your looms there was a tramp weaver on. How did that change during the second world war?

R- During the war, there weren’t any during the war, they’d to be working, they could get work anywhere, there were no tramp weavers. But you did as you liked as regards going to your work. The time you went to your work.

So the old discipline slacked off a bit in the mill. Now another thing about that, would this be about the time when the tacklers, the overlookers, perhaps lost a bit of their power? Do you think that’s fair to say Horace?

R- Well, I don’t know about that, they were always very strong you know? But it got to be like this, they’d turn up any time would people, tackler or anybody. They always used to lock the door but they used to go back home again you see? And they were sending for them, knocking at the door. It’s altered so much you see, they couldn’t do without a tackler for a set of looms. They’d say ‘Where’s suchabody?’ ‘Oh, he’s been and the door were locked and he’s gone back home.’ So they stopped locking the door.

Aye.

R- And I were working [at Rycrofts] and going on me bicycle. Well, August and September, when there were plenty of mushrooms about, I’d go out into the field and mushrooming and happen land at quarter to eight instead of seven o’clock with a stone of mushrooms. They couldn’t do anything because I were wanting to finish.

(550)

(25 min)

Stuck there doing nothing and working for nothing and they were business people were Rycrofts but they were tight folk. And they [the workers] used to get fed up. “Everybody working here for this money, let’s go down in the office! It’s all right when you go down into the office.” And there were weavers, as always, some wanted to go and some didn’t. And finally, “We’ll go down this afternoon.” Then you go and knock at the office door and the office lass would come to the door and “What do you want?” You had to tell ‘em what you wanted and “I’ll go and see what he has to say.” And it were always the same tale “I’m very busy now, I’ve a traveller in I’ve got a meeting. Just go back to your work and I’ll send for you tomorrow when I’m at liberty” Well, once he could do that, all the fire had gone out of them. It took a lot to get them all of one mind, to repeat the same thing. And if you did get to see him, if he sent for you, perhaps next day or the day after, or if it were Monday you went in, Tuesday were market day so they were off, nobody there. And then if you didn't catch him at Wednesday, they were down to Bradford at Thursday, well it’d happen dribble on to the next Monday. Well, you'd lost all the enthusiasm the weavers had before they went the first time. But they were crafty enough. [The bosses]

When did you first see this? When did you first join a union? Was it while… ?

R- When I went to Rycrofts, they were on to you immediately.

Aye. That was when you started at Rycrofts?

R- Started at Rycrofts.

So that’d be 1920?

R- No, 1925 or 1926. Yes, I were about 21 years old.

So they’d be on to you straight away, the union. And what union did you join there Horace?

R- It wore the Clothlookers, warehouse men. And they had an office at Colne..

How much good did they do you'?

R- Well, they couldn't get you any more money. I mean they used to apply but that were all. They couldn't do anything until the war started you see, and all the men left that could leave. A chap that wasn’t of military age, you see they couldn’t do anything with him, they could just go. But the older men stuck it, they were living nearby, their homes were near to their work.

(600)

When did you first start to regard the Union as a body that could do something for you? You know, when did they start to gain a bit of power? Was it when labour got short during the war?

R- Well you felt you’d a bit of power when you were all united. One man on his own couldn’t do anything you see. If you were all in a union, well, any trouble you just report it to the union and left it to them to do what they could.

Were you ever brought out on strike while you were at Rycrofts?

R- No. No, I don't think so. Perhaps once. Yes, it would be just once, all the weavers, and it was one of these where you came out and the next day you went back in with a half crown in the pound deduction. That’s the way it used to be.

Aye. In all your experience up to, let’s say up to the second world war, the start of the second world war. Do you know of any instance where anybody in textiles went out on strike and actually gained an advance in wages?

R- Not previous to the war.

No. Have you ever seen the textiles go out and get an advance since the beginning of the war?

R- No, I can’t remember us ever being on strike. Not since the war because it were all negotiated by the unions.

When you came to Earby as oiler on the engine did you still stay on in the same union or join another union or just let your payments lapse?

R- I let it lapse.

So while you were working with Billy Lancaster on this engine down here you wouldn’t be in a union?

R- No.

Well I think we’ll quietly come back to here then. When you came to Earby to work, obviously you were living in Earby, when you came to Earby to work at the Big Mill, what was your general impression when you first came of .. you know, the mill, the state of the plant, anything at all?

R- Well when Johnsons took that mill there, I knew Bill Lancaster like, I’d known him all the time. Well since he used to run the engine at Broughton Road. I knew him all that time and then I used to travel with him on the train you see. People of one place always used to crowd into one or two carriages, same lot every night. And he told us about Johnsons taking this place and says “You mun come down tonight and I’ll take you round.” And I were amazed, everything painted, walls painted, electric lights, steam pipes painted with aluminium paint, not a speck of dust anywhere, everything painted. I’d never seen anything like it.

This was Johnson’s part of the Mill, yes?

R- Johnsons yes.

And did that compare with Rycrofts?

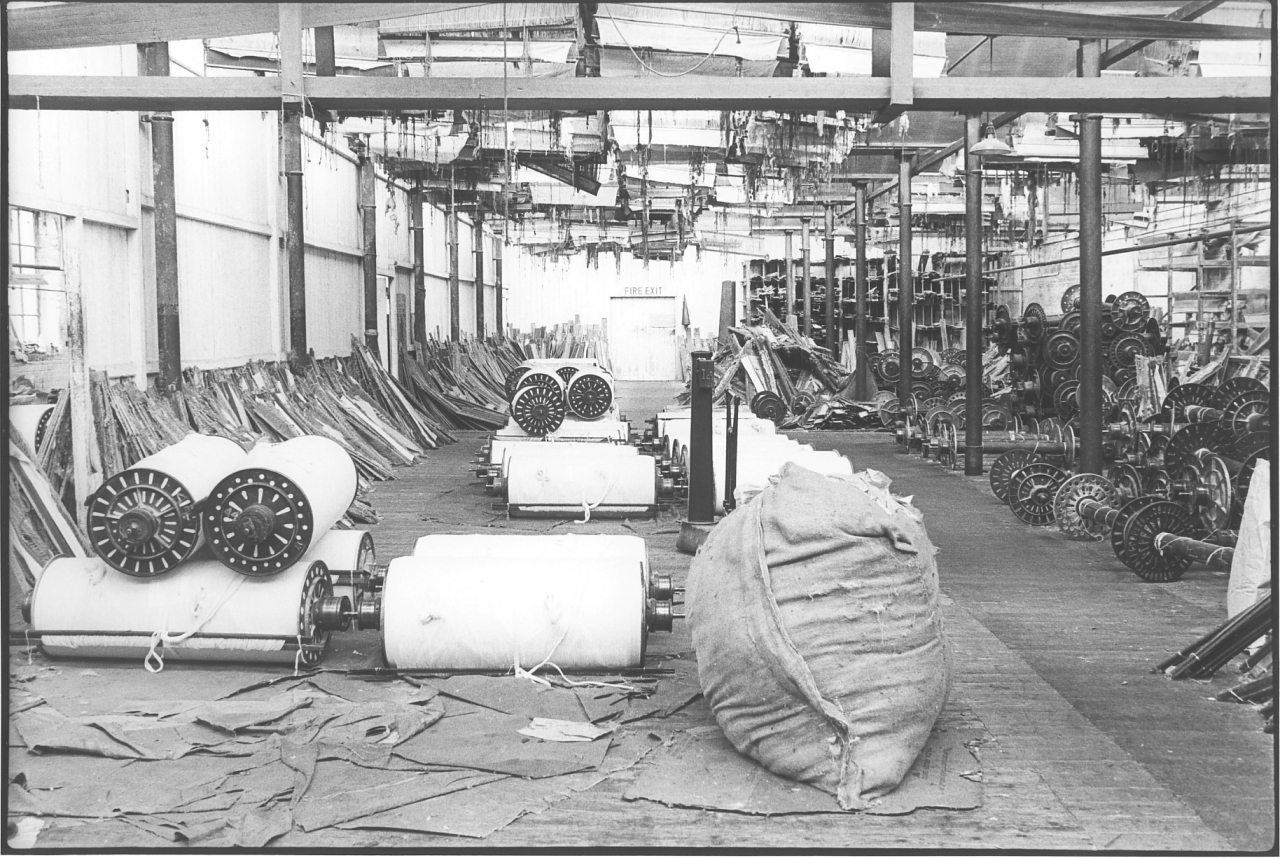

R- Well it were just ordinary paint. What they did was paint every five year, if they did, and whitewash every twelve months. But during the war years that were waved to one side. They swept but it wasn’t clean. They might have thought it were clean but . this was like a palace, all one colour, a nice blue grey paint, everything. Oh it were a revelation. Floors clean you know no mess about. Now the other place, the other shed at the other side, when you went working in there and you were doing anything you could just touch the thick dawn [Dawn is the name we gave to the fine cotton fibres that clung to everything in the mill. My mother used to tell me that I was ‘Worse than dirt dawn!” when she sauced me.] on the steam pipe, just give it a push and it’d run off, run off the full length of the weaving shed, just same as a long sausage, that were how dirty they were. They swept the floors and the looms and that were all they did. It wore just like this place, it were just in such a state as that mill you were showing me. And the tape.

Aye. Bancroft, that's it. And how about the condition of the plant, boilers, the engine and such as that?

R- Well they were just falling in bits. Everywhere, everything were just [a mess]. Well, when I first went, my first impression of the engine, I went underneath it and everything were rocking, the air pumps, you went on down the steps and onto the iron grates in between them, you’d to watch when you were passing

(700)

and make a rush to get past, if you didn’t, when these flanges opened, water came out like a hosepipe and that’s what you had to do, just dart through at the opportune moment.

Aye, that was the old air pumps that Newton, well Johnny and Newton replaced wasn’t it.

R- Yes, it were all right after that. But in summer time we used to lose the vacuum, and so all we had to do was fix a hosepipe on to a hydrant, just outside the engine room door and get the grate open, have the hosepipe running into the top of the air pumps you see to cool them down. [Victoria had a poor condenser pond and in summer when the beck was low they often ran short of water for the air pumps. This was exacerbated by the poor condition of the plant and was eventually cured when Brown and Pickles replaced the air pumps. See the AG series of tapes.] And one night when we’d stopped we just took the hosepipe off, whoever had done it I don’t know, it could have been me or it could have been my mate. It could have been Lancaster. We took the hosepipe off but didn’t shut the valve. We hadn’t taken the hosepipe off, just dragged it out of the air pumps and dragged into what they called the ballroom and left it like that ready for morning but hadn’t shut the valve. [What Horace hasn’t made clear is that the hydrant was fed off the steam fire pump and once this was stopped, no water would run. What followed was a consequence of starting the fire pump without making sure that no other hoses were connected. In many mills the fire pump was used as a feed pump for topping up the boilers. This was very bad practice and again, a consequence of bad maintenance, but common practice as it was an easy way out.] Well, the boilerman came on after tea, he must have been short of water [in the boilers] and he started the fire pump up to fill the boilers up. He weren’t an experienced man, he’d worked at Gargrave and they only wanted a bit of steam, 30 or 40 psi, that was all he’d been used to. And he started the fire engine up and couldn’t get no water in the boiler. He went on about a couple of hours and we were and we were working inside in the shed somewhere on the engine, and we didn’t take any notice of what were going on, it weren’t our department. We heard it clanking [the fire pump] and then he come in and he said “I can’t get no water into the boiler.”

(35 min)

So “Come and have a look at it.” Oh my God! He’d been pumping that hosepipe full bore into the ballroom and it was running through the floor and on to all the Newbridge cloth down below, running out of the door there into the drains. I mean he were a numbskull to go on all that time pumping away and nothing doing but he thought that the fire pump weren’t working. It were hit and miss job ‘cause I told you about the clack had gone down in the well.

Aye, when you went to it and took the pipe out of the well and the clack was missing altogether at the bottom of it.

R- Yes, there were just a bit of the metal part, all the leathers had gone. And talk about going hot and cold! When we rushed down below we were in a state! And what had saved them, there wore piles of silk, all over the place, but every one had a big sheet of paper over, Kraft, that Kraft paper, right strong paper. And every one were covered with sheets of paper, and the water had just run off and dropped on to the floor. There were just the selvedges, some of them were wet. And so we’d to set to sweeping it out, sweeping it out of the ballroom down the steps. I could write a book on the mishaps that there were there.

[A word about what was going on here as it is very good evidence of the state of maintenance that Horace was describing. One initial point, the problem he is describing isn’t due to wartime shortages, it is down to inadequate maintenance, probably due to old Bill Lancaster reaching the end of his time and letting things go. When Horace says the boilerman came back after tea to fill his boilers this is an indication that the boiler feed water pumps were in bad condition, almost certainly just a matter of grinding the clack valves in. This meant that during the course of the day the boilerman was losing his water level. This is no big problem with a Lancashire boiler, as long as the water level is above the bottom nut on the water gauge glasses you are perfectly safe. What he had done was go home, have his tea and come back to get his water level up for the following morning’s start. The feed pumps at Victoria ran off the engine and when it was stopped the only recourse he had was the steam driven fire pump. This pump is not intended for this duty, it pulls off the mains water supply and is not metered so though illegal, it is a cheap source of water. They evidently had a permanent connection into the feed water main, probably an insurance requirement as they had no independent feed pump. In addition, Horace had told me that the fire pump was not reliable because the clack valve seating in the well was worn out and allowed the pump to lose it’s water in the riser pipe. It was touch and go whether it would prime itself at the best of times. Bad maintenance again. So, when the boilerman started the pump and got no water he assumed it was the clack and it might eventually pick up. In fact what was happening was that the pump was working normally but because it was pumping against an open hose in the Ballroom there was no delivery against the boiler pressure. All told a sorry tale, the root of which was bad maintenance all round. Incidentally, the Ballroom was the name for the second floor in the old multi-storey section of Victoria Mill. When Horace talks about loose rivets in the boiler in the section below, this is almost certainly a direct result of pumping large amounts of cold water into a hot boiler with the fire pump. ]

Aye, well that’s what we are doing Horace, that’s what we are doing. This is all part of the job, these are the things that happened.

R- They did but oh dear… the various things that happened. How that engine ran I don’t know. And we were having a lot of trouble with the boilers after that, the way it had been running without water and it’d stretched all the plates and they pushed them back, next boiler there were rivets going and they were coming every week and doing a bit at it. And the boiler front rivets were stretched there and they [the insurance surveyors] were coming every week, they wanted the mill owners [to do something about it] So we had the [stoker] hoppers to take off every Friday night when they finished. Strip them down, carry them away so the men could come in and work on putting fresh rivets in.

(40 min)

Who were it that came?

R- The boiler makers, Yates and Thom.

Yates and Thom from Blackburn.

R- They used to come and work the week end and then it got to Sunday tea time, they’d go and we’d all that boiler front to put on and get steam up on that boiler. We had the other two boilers going. But I got to the stage, you know there was a big plate to crane off but I got to know every bit of them, them hoppers, I could have taken them off and replaced them blindfold!

Aye, that’s the way to learn Horace!

R- But it went on week after week. I were never at home, working nights and working through the night and then going on steaming. The wife weren't used to that sort of work, she thought I was at a madhouse.

Tell me about some of the problems, some of the simple little problems that you met up with. Just doing simple things like going down and steaming the shed at night to get it warm.

R- Well the traps used to freeze up but they solved that. All the steam were returned into a tank, there were no traps blowing out. You see if they’d been stood all Saturday and freezing that water in the traps. There were all sorts of things but that were the worse do when I’d to cut a split pipe off that went across from the engine house to the boiler and thread a couple of pipes and fit them, all on your own up a ladder and just a gas lamp on the wall outside the Devil Hole [The cellar that housed the waste breaking machines in the old days, they were called devils because they frequently caught fire.] They had no electricity then, and the light were shining up, depth of winter and I thought “Oh my God, What a bloody fool you’ve been to come to this place!”

Tell me something, I think I'm right in saying that when you went there, there wasn’t even electric light in the engine house.

R- There wasn’t no. It happened after a while. Why they didn't have electric light, the room and power company were the Earby Light and Gas company. And you couldn’t have electric light, you had got to have gas and the whole of the sheds

were all lit by gas. They built a new plant down here, on the New Road here and it hardly ever ran, there were a man killed when they were trying it.

That was a gas plant?

R- Gas plant. Built a new gas plant and so they had a pipe put into Barnoldswick and Barnoldswick supplied Earby Gas and Light Company and they supplied the customers in Earby. But it was a private company until the gas were nationalised.

So that electric [going in] I know Newton told me that it was when Rigby was down there. What was his name?

R- Henry Rigby?

When Henry Rigby went to do for Billy, because Billy was poorly for a long time.

R- Oh he were off a couple of years.

Billy was a poorly man, wasn’t he.

R- Aye. But many a time we was on us own you see. But I tell you, that particular day when Wilf McKie, his wife were dying of consumption,

He was your mate on the boilers and the engine?

R- Yes, and he were a good man to work with, he were a good lad.

And Billy were off as well, Billy Lancaster?

R- Billy were off as well. Boiler man hadn’t turned up, a man called Lindsay, his wife were ill and I were stuck there by meself in winter time. When I told the tale I said “If there isn’t something done by breakfast time I’m going and all!”

(850)

So you had three boilers, the engine and all the shafting to look after.

R- Yes, all that. And then Teddy Wood came on in the middle of the morning. “Keep it going, keep it going, and if anything happens to Bill the engine’s yours!” I said “It’s a bloody tale, I wouldn’t have it given!” And I wouldn’t, a bundle of old iron it were. Everywhere, slates off the roof, windows out, sheer neglect. Boiler house roof, rain coming in.

What was the reason for that? I mean, when you think about it, surely these men had the sense to realise that the power unit was everything? You’d have thought that they’d have looked after it.

R- They’d that few tenants, and the tenants they had they perhaps weren't getting there rent. They were small firms in that far side. Birleys used to be there and they’d left and gone over to the Albion so that were all empty. How long it were empty I don’t know but when Johnsons come they said we must have electric light or we won’t have it. So, Johnsons had electric light and the other parts of the mill hadn’t. Now when they became nationalized it didn’t matter then but before that…

When who was nationalised?

R- The gas works.

Aye, that’s it.

R- It didn’t matter, they didn’t care. So all the other firms, they put electric lighting in for the other firms. And we had a dynamo run of the engine you see to light the engine house and the boiler house. We used to have 12 volt lamps to go in to the boilers. We’d old Smokey Joes before.

Aye with stink lamps as we used to call them.

R- Stink lamps, aye. That’s what you went into the boilers with, scaling and cleaning out.

Aye, what were it like for scale down there, what were the water like?

R- Well, sheer neglect, you could get, you could get lumps off like layers of flags. . You could, it were just like hacking layers of flag off. But you see when it were all empty here and the other tenants couldn’t afford to pay there’d be hardly enough money to keep the plant going at all, pay the wages and pay for the coal. I think they’d been charging, before the war, about half a crown a loom. I don’t know how much for a tape but I think that’s what it was. I saw some bills, so many looms. at half a crown a loom, and glad to get them at that.

(900)

I know I’ve heard people say that just before the war it was possible to buy Calf Hall Shed Company shares for nowt.

R- Yes they could.

And I dare say the Earby Shed Company and companies like the Mill Company would be the same.

R- Well, I don’t know whether Johnsons have any of the right old Lancashire looms yet but when they started those looms cost a pound apiece and they just ran on and on.

I think they still have some of those looms in.

R- Yes I think they will have.

Because when they did them up, the last modernisation, they threw all the automatics and broad looms out and just kept the old Lancashires.

R- Yes, they were just useless but it were government money that. I think they were getting something for nothing. This fancy tape, well it were just a dead loss absolutely, and the looms were, well, there were top shafts breaking at the rate of six and eight a week. Have you ever known that…?

SCG/27 March 2003

7,303 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 79/AD/12

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 17TH OF JULY 1979 AT 16 COWGILL STREET, EARBY. THE INFORMANT IS HORACE THORNTON, TAPER AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

So, the picture we're getting Horace is the fact that there is no doubt about it that the Big Mill at Earby was in a fairly run down condition but that that was really due to the fact that it wasn’t a paying proposition, and then there had been the war years. But I think I'm right in saying that it did get to the stage where there was an alteration and that was while you were working there. Now, can you tell me about it?

R- Well, they’d more money to spend. All the space were let, everybody working full time. Before the war half of the place was empty, the ballroom were empty, well Johnsons took that and the Big Mill, Victoria Shed. Birleys used to be there, well they moved out, I don’t know how many years it was empty, and Johnsons took that, well everything was running. They’re drawing quite a lot of money every month and they had something to spare

(50)

then because if they hadn’t spent it they’d have been having to pay it in Income Tax. Because Bill Lancaster once told me how many hundred pounds he had to spend that year. That were excess profit and more got done you see. We got a three throw

pump for pumping the water back into the boiler and more steam pipes in, less waste and we started getting more repairs done whereas before that there’d been 20, well 30 years of neglect.

Newton told me that one of the things that started the job off was they went down, they were asked to go down at one time, well, you’d got to the stage where the engine was only just keeping up with the load. So they went down and I think you know a bit about that.

R- Yes, we’d a job to keep going. Well, everything was on, I think Johnsons [870 looms] had five tapes, Charles Shuttleworth [604 looms] had a tape and Hugh Currer’s [684 looms Earby Manufacturing Company] had a tape. Well you see there were seven tapes going. I think that’s correct, six or seven tapes going, and every available space had a loom in, there was a lot of weight on an old engine like that. And in the boiler room, everything were run down. We started getting new hoppers you see, whereas they had been tied up with bits of wires before, and it were just sheer neglect because they’d no money.

And then they brought Brown and Pickles down to have a look at the engine because it got to the stage where the boilers couldn’t make enough steam to keep the place going could they?

R- Keep it going, yes.

And apart from the coal they were burning. How much did they get up to a week?