This is tape 78/A1/01.

The informant is Arthur Entwistle who is a retired engineer who now lives at Stratford-on Avon but was born in Barnoldswick and left the town in I think the 1930's. He is 70 years old and he's staying with me for a week. He's a personal friend of mine actually but I want to interview him for his knowledge of the town in those days and also the reasons why he left the town when everybody else was going into textiles. Now one thing about Arthur, he's just had an operation for the removal of one lung. and has lung cancer, so he's very, very softly spoken. I shall do the best I can but we shall have to see how we go on with these tapes.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 78/AL/01

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 17th OF SEPTEMBER 1978 AT HEY FARM, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS ARTHUR ENTWISTLE, RETIRED ENGINEER AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

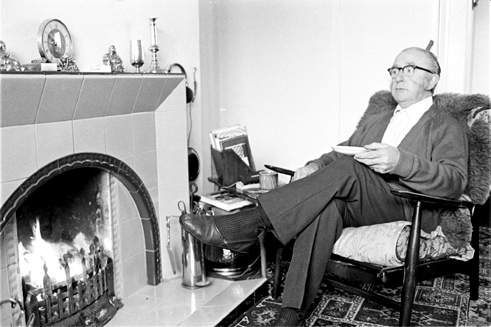

Arthur Entwistle at home.

You’ll find this is a very relaxed thing to do. I’m not, this isn't studio recording we’re not bothered if the cat farts under the bed, we're not bothered about that at all. What we want is the information and funnily enough as you start to get relaxed and it starts to come out it gets so that it is to all intents and purposes a studio recording. I think so anyway. Anyway that's my tale, I'll start now. How old are you Arthur?

R - Seventy one this month, 24th of September.

And you were born..?

R - 1907. 24th of September.

24th of September 1907.

R - 1907 yes.

And where were you born?

R - Born in Barnoldswick. I was born in Market Street, No.9 and lived there until the war broke out.

Yes.

R - I don't know whether that's relevant or not.

Oh yes, yes we'll get round to that. I shall get round to that. You're alreight Arthur. Market Street, which is Market Street?

R - Well, you know where the Ivory Hall Club Is? Well If you went down that side street from the Ivory Hall Club, say you was going from here you'd go down a little slope wouldn't you then there's a succession of streets running into Newtown.

That's it.

R - Well there’s Orchard Street and Market Street.

That's it aye and Garden Street an all.

R - Well Market Street in my early days. The only recollection, one vivid recollection I have, it was one Christmas, I had two aunts died and buried in the same week.

Yes.

R - Christmas week.

Yes well we'll get round to that, you’ll be surprised what you will remember about that before you've finished. Anyway, how many years did you live in the house that you were born in, that’s at Market Street?

(50)

R - Not many years, as a matter of fact to be quite honest about it I can't remember myself living there. I can only remember my grandmother living in that street if you understand what I mean.

Yes that's it, so the family moved when you were fairly young.

R - The family moved when I was fairly young. I don’t know whether you want to know the first recollection of where I lived.

Yes, which is the first house you remember?

R - Well the first house I remember has disappeared now. It was at the bottom of Manchester Road which many years later became a barber's shop. But I remember being frightened by the first motor lorry I ever saw.

Now this house that used to be a barber's shop, that ud be the house that's, it's a newsagents now is it? Next to the Seven Stars.

R- No it’s disappeared.

Whereabouts was it then?

R - Well you know where they've cut the corner off at the bottom of Manchester Road onto Church Street? They've cut that corner off.

Yes, that's it. yes.

R - Well there was a barbers shop there and houses. And that's where I first remember. I was only quite young, I know I ran into the house screaming and the vivid thing I remember about that was, those days the wheels were wooden spokes with a hub cap like they have on the old cars.

Aye.

R- A brass cap, and that were the thing that frightened me.

(5 mins)

Aye. So how old would you be when you were living in that house?

R - I should be about two years old.

Oh well that's not so long. And how long did you live in that house there?

R - Well a number of years. The time factor didn't seem to mean a lot to us when we were that age, and there are only certain things in life give you a vivid remembrance. The second one was being taken to the doctors on Jepp Hill where the town hall was or is, to have a boil lanced off me backside. I was so young, in those days it wasn't customary to breech a boy until he was about four or just prior to going to school, so he was dressed in petticoat's like a girl. That was a painful recollection, ‘cause as I say I went to the doctors to have this boil lanced. Do you want to know where I moved from there?

Yes well I’ll keep you going with questions. Now have you any idea why the family moved from Market Street to the bottom of Manchester Road?

R - No 1 haven’t.

No it's all right if you haven't that's....

R- I have a surmise which may be incorrect and may be doing an injustice but there was a question of arrears of rent. I don’t know.

Aye, well that's, well I mean that's common but as I say that doesn’t matter. Now what was the next house you moved into?

R - We moved down into Twenty Row. (Wellhouse Street)

(100)

Which is Twenty Row?

R- Well, you go down Wellhouse Road and there's your Avenues on your left hand side and then you turn up and you can go on to Rainhall Road. And then there's streets running along there that's 19 Row and 20 Row.

That's the same row that the Co-op Hall is on.

R- Possibly yes.

That's it yes. And how old would you be when you moved into Twenty Row?

R - I should say four years old.

Aye. And how long did you stop in that house?

R- We stopped in that house until the beginning of 1914.

So you'd be about six year old. So you’d only been in that house about two years.

R- Six. I was going to school.

Aye, you'd only be in that house about two year then.

R - That's all,

Where did you move to from Twenty Row?

R -Well we moved down to what they commonly call China Town. I'm trying to think of the name of the street which eludes me at the moment.

That's right.

R – It’s the last street going down Gisburn Street. [Colin Street] (1912)

Yes.

R - The last row of houses. And there was no more built there because war broke out.

That’s it, and how long did you live in that house down there?

R- We lived in that house two years because me dad joined up on the day after war was declared for some reason or other. The day after war was declared he joined up immediately and he thought it would be better if me mother moved near to where his father and mother lived. For what reason I don't know. One can't say it was for mutual protection because there was no danger to civilians then. But anyway we moved to Padiham in the same street as his father lived in. (1914) Well I say we moved to Padiham, we moved to Hapton first, a little village just outside, and as soon as a house became vacant in Padiham, what was called the Green, we moved there. And why I remember so much about that is I was sent to a Catholic School and being moved about, young as I was, every fresh school that I went to I had to have a fight on the first day I went to school to establish whether I were duff or not.

And how long did you live at Padiham?

R- Well we lived in Padiham until early 1917 and I think

(150) (10 mins)

there was some domestic upheaval. At my age at that time these things don't become apparent but I think the old man suspected that mother had another chap but the truth of the matter was he’d made an alliance with another woman and he were just trying to make trouble. ‘Cause I remember him promising me a wrist watch if I told him certain things I couldn't tell him because I didn’t know if you follow what I mean.

Yes.

R - And that would be 1917. The result was a family disagreement with his father, my grandfather. Its an amusing thing, I might just put this in, symptomatic of the times. The old man, it was his second wife and in those days of course they had the coal man coming and the clothing club man coming, they had the rent man coming and other small petty collectors every week. And times being what they were, they'd get the single bed downstairs and buy the old chap a couple of pints and get him to be in bed while the collectors had come, he was an invalid. As soon as the collectors had all gone, back up stairs went the bed and off to the pub went the old man to spend his earnings. Anyway, however, we came back to Barnoldswick and we got into a house in Orchard Street, very primitive. There was one room downstairs, there was one bedroom upstairs and the secondary bedroom, if you can visualise a bedroom with half a roof or loft as you might term it. Me sister and I had to go up this specially made ladder and we slept in the loft, and then the old man he got, well 1 wouldn't say wounded, he was invalided home with trench foot. That was very early 1918 and he spent very nearly a year in Keighley Military Hospital.

That house in, what was it Orchard Street.

R - Orchard Street.

How long did you stop there?

R- We didn't stop long after me dad came home, well I say came out of the army, when he was invalided over to the hospital, 'cause we never knew whether he might have to go back to the war but we got this house, number 7. St James Square

(200)

and lived there until 1924/5. 1925 from 1918.

So that were the house you were in longest actually.

R- That were the house we lived in longest.

And you went into that house, what did you say, 1918?

R- 1918.

So you'd be ten year old roughly.

R - Yes.

So you'll have a fair few recollections about that house in St. James' Square won't .you?

R- Oh yes. Definitely.

Well what I’m going to ask you some questions now. I'll be getting on to some questions about the home, you know, and the house. Well they’ll be about that house in St. James' Square. What number was it?

R- Seven.

They'll be about 7 St. James’ Square. Now that’s just to keep you orientated you know, and then. Because you did shift about quite a lot, but that's quite a good age that, ten year old in 1918 you see. Now where was your father born?

R- Verbally, from verbal statements he was born at Mill Hill near Blackburn.

Aye. And why did he come here?

R- Now, he served his time with Howard and Bullough.

(15 mins)

As an engineer.

R- As a, well as an engineer yes and he was always a man with a violent and fierce temper. And what one would call the overseer or charge hand today, he fell foul of this fellow, and I think this fellow, as was customary in those days, thumped him. Anyway the old man waited. As you know the sanitation in those days wasn't very brilliant. There was a row of cubicles outside, little buildings with a door on, a tub and a trap door at the back to drag the tub out, a limited amount of privacy. I know this again is recollecting an anecdote that the old man told about this affair after the charge hand had thumped him. He waited cunningly until this bloke went to the toilet and of course in those days all the machinery was driven from one central engine by shafting and belting and they used to use on the belts to stop 'em slipping what they called 'Black Jack'. Now from what I can gather this was not exactly like tar, more cottony but still adhesive. I know the old chap waited until he went to the toilet,

(250)

the story goes, and he’d marked out which one he went to. He craftily opened the back door a little bit and he got his 'Black jack' stick and tin and he just slapped this bloke on the backside and his privates and buggered off and joined the navy. When I say he joined the navy, he joined the Royal Marines. That were before, that was when he was a young lad as you might say, young fella.

That's it aye, So he had to leave Blackburn then there’d be no work.

R- Well he went and enlisted straight away. I mention this because you say how did he come to leave Mill Hill and come to Barlick. Well when he came out of the Royal Marines he came to Barnoldswick for some reason or another, where of course eventually he met and married me mother and that's how he settled down in this town and held various occupations. Those days if you'd eighteen and six (18/6d) a week wage, I'm speaking of before the first war, I'm goings back now before the war, you wasn't doing so badly. He made this from bicycle repairs and that. Newsome's used to have a shop at bottom of Jepp Hill. This is next to that paper shop now.

Yes. We'll get round to jobs in a minute Arthur. Now where was your mother born?

R- My mother was born at Low Moor, Clitheroe.

Aye. What was her date of birth?

R - Oh dear, no.

What year did she die?

R- I know this might sound funny to you but 1 can't remember.

It's quite common Arthur, it's quite common.

R- The only thing 1 do remember about it is that she died on the day which would have been my birthday but the year....

That’s quite common, don’t let it worry you. You'd be surprised it might come back to you. Did you have any brothers and sisters?

R - Well, yes. If the family as a whole had survived there would have been thirteen children.

(300)

Now that's it, you just hold on a minute now. This again is common, how many confinements did you mother have?

R - Well It's quite possible she could have had fourteen or fifteen if you count miscarriages.

No that's confinements, that's how many times she was actually.,

R- Actually confined, thirteen.

(20 mins)

Oh I see. She had a couple of miscarriages. I was wrong there Arthur. So now, of the confinements how many children survived? How many survived the first two or three days, that got to be any age at all?

R- The first one died, be about seven months old, and there again I'm speaking from recollecting what our parents said. This child apparently was abnormally intelligent, uncannily so. If I'd believe what my mother and father said, this child could pick with one finger a tune out on the piano. But he died as a result of vaccination.

So how many children, let's get at it from the other end. How many children actually survived?

R - How many children survived, four of us that's all,

Four, and roughly what age did the others die at?

R- Well an far as I can remember it varied between six months old and two years old.

Yes. That's fairly common again Arthur. Have you any idea what the causes of death were? You said the first one was vaccination?

R- Well, my recollection, I could say partially malnutrition.

Were any of them born after you? Whereabouts did you come in the family?

R- There was one born before me, the one I've just mentioned who could play on the piano.

So in actual fact you are the oldest surviving child.

R- I’m the oldest surviving.

The oldest survivor of four children.

R- Yes. My sister was two years younger than I.

What was her name?

(350)

R- There was children born in the intervening years, the war of course upset things a little bit. After the war I had another brother born, Owen.

What was your sisters name?

R - Evelyn Maude.

And what was your brothers name?

R- Owen was born just as 1 started work.

That's it, and then there’ll be another one.

R- And then there was Cyril born two years after him. That was the last child born in the family.

So that's three brothers and one sister. [in the family]

R - Yes.

Reight. When you were a child can you ever remember any relations living with you in the house?

R- Not really, no.

We're talking, remember we're talking about the house in St. James Square now.

R- Yes. Ah now then, relations living with us in the house. Well not until 1 was about eighteen and we moved, we had a relations come to live with us, a cousin.

When you say a cousin was it male or female?

R- Male cousin.

Yes, why did he come to live with you?

R- On the distaff side. He was local, a local boy. He was born in Barnoldswick like I was but his mother, she wasn't over educated but she had a reputation of getting lots of girls out of trouble. In other words what is now considered a highly profitable profession of creating an abortion. Which she got many a girl out of trouble and of course finally, and it does happen in these cases, something went wrong and she was sent to Strangeways prison.

What was her name Arthur?

R- Margaret Macdonald.

Any idea where she lived?

R- Yes she lived at the top of Wapping, what I believe, is it Esp Lane?

Yes that's it.

R- She lived down there. Well I should say till she practically died there. I left this area a good few years ago as you remember.

Yes that's it. What year would that be about? When she went to Strangeways?

R- Let's think again. 1926 approximately.

Good. You see you're doing well on your dates. You'll be surprised..

R- The family was split up. One boy came to live with us and the girl and another boy went with other members of the family for the terms that she was in prison.

(25 mins)

And how long was he with you?

R- Well he was still there after I got married, which would be 1928 so he was there a year or two.

1928 you got married.

R - Yes.

Now, did the family ever have any lodgers?

Not in my living memory, although I heard that my dad had his brother lodging with him for a while until he got married. Which was probably before I was thought of or I came on the scene.

What was your fathers job when you were born do you know?

R- Well on my birth certificate he's listed as a gas fitter. Because in those days there was no electric in the town of course and it wasn't every house that was connected with gas. I'm happen jumping ahead a little bit but 1 remember as a boy going with me dad and helping him to put gas in. Lots of houses only had gas down stairs.

And when you were In St. James Square your father ud come back from the war. What was his job then?

R- He went working on the railway as a porter.

How long did he stay as a porter on the railway?

R – Oh, 1919..I should say about six or seven years at the most.

So that ud be from 1919 to about 1926. 1926/27?

R- When was the great strike. General strike, he was working on the railway then and I think he finished just afterwards. I think it was 1926 the great strike, the general strike.

(450)

When the miners and everything came out. ‘Cause I remember there wasn't a saw to be bought in the town and there wasn't an axe because everybody was going out chopping fencing down and chopping trees down.

Did he have any other jobs after that?

R – What, me father?

Yes. When he finished being a porter what did he do then?

R- He went in the factory, cotton factory.

Which one?

R - Let me see, I think it were Edmondson's, Fernbank, which is cotton trade.

What was he doing there, do you know?

R- Sweeping.

That ud be about 1927.

R- Thereabouts. Yes it would be 1927 yes.

1927. That's very early for sweepers, very early for sweepers.

R- There were sweepers there then,

Yes. As I say it was very early for sweepers though that date. Now when he was working for the railway he’d be working for the Barlick Railway of course wouldn't he.

R- That's right. Well the LMS.

[It would be the Midland Railway when Arthur’s dad first went to work for them. The London Midland and Scottish Railway was formed in 1923 following the Railways Act of 1921. The Barnoldswick Railway had been run by the Midland from its inception, opened Feb 8th 1871. Closed to passengers 27th September 1965 and to freight on 1st August 1966 but was taken over by Midland in 1898.]

And he was not only stationed here, he graduated to be good enough to be a relief porter and if someone was on holiday at a remote country station such as Appleby, places like that, Ribblehead where you had a station master, one porter who was clerk. ticket collector and what have you he [went as a relief] I remember because I spent one jolly good holiday at Ribblehead while he was working on the railway, watching the Flying Scotsman come up and come down.

We'll get round to that an all. Now what was your mother’s job Arthur,

R- Weaver all her life. A cotton weaver all her life, yes.

(500) (30 mins)

Can you remember any of the firms that she worked at?

R- Well the names unfortunately would elude me.

Well the mills then, that'll be good enough Arthur.

R- Butts, Pickles, sheeting shop down at Westfield, Hartley Edmondson’s at Fernbank. Sheeting shop over the Coates and I think she finished her weaving days at Edmondson’s Fernbank.

So was she weaving while you were young, while you were being brought up. Let's say St. James Square.

R- Well, we’re going back before St James Square if you want to know about her weaving.

R- Because it was customary in those days for women in the cotton trade, I can remember being carried out to be looked after by my grandmother, wrapped in a shawl, before six o'clock in a morning. To be left with me grandmother for to be nursed while me mother was working, at Coates Mill then. And I remember her telling that the icy conditions were such and so bad that they used to have to take their clogs off at the bottom of Coates Bridge and go up more or less on their hands and knees. Working conditions as far as I can recollect were not too favourable for the textile workers. ‘Cause I remember vividly being carried out. Why I remember it is the sparkling frost of the street lamps which seemed to be deeply impressed on my memory, snuggled in the warmth against my mothers breast and under the shawl.

(550)

And so if she was taking you out to a child minder and you were the eldest of the survivors she'd also have the younger children to take out as well.

R- I might sound to be boasting here when I say my memory goes back quite a long way, and at that time I don’t think my sister was born. I could only have been about eighteen months old.

Yes, so can you remember how long would it be after, say the birth of your sister or one of your brothers, before your mother went back to work?

R- Well, economically it was essential. While grandmother was living of course she was always there as child minder. But I've seen, I've know me mother be back at work no more than a month after the termination of the pregnancy.

Would she be breast feeding her children then?

R- I can’t recollect her breast feeding any of the children. She might have done but not to my knowledge. Well, put it this way, I don’t remember seeing her breast feeding.

That'll do Arthur you can’t do any better than that. How old was she when she died?

R- She would be about sixty four.

Now apart from you, because obviously I know that you left the town but did any other members of the family leave the town. When did you leave the town Arthur? What date was it about, roughly?

R - When I left Barnoldswick? In my more adult years as you might say, after I was married. I left Barnoldswick on New Years day in 1939.

Yes. Now did any of your brothers or sisters leave the town?

R- Not at that date, not until I got settled and then it was inevitable of course, I had one brother that was serving his time at 7/6d a week, and I got him a job and he came to live with Amy and I.

(600)

Who was that?

R- Cyril and then we got Owen down later. Owen was an apprenticed bricklayer and he worked on the new school on the New Road.

What was your sister's name?

R- Emily Maude.

(35 mins)

Did she stay in the town or did she move down as well.

R- She married a boy in Nelson and lived in Nelson until her husband was called up into the navy. When he joined the navy she came down to live with me mother and father and unfortunately her husband never came back.

Now when you say came down to live with mother and father, did they move down to the Midlands as well?

R- As I said, once I got settled not only did my brothers come down prior to my mother and father coming down. I had them and then me mother and father come down and I also had an uncle and aunt came down.

Aye. So there was a wholesale exodus of the Entwistle family from Barlick!

R- That's right. And some Fishwicks.

And Fishwicks aye, Fishwicks. That was your mothers maiden name was it?

R- No, me sisters married name.

Aye. Narthen, this house in St James Square, how many bedrooms did it have?

R- Two.

What other rooms were there?

R - There was two rooms downstairs with a very small kitchen. When I say a small kitchen it was a queer house because

(600)

one room was triangular, which the bedroom above of course would be. And part of the triangular room downstairs which was on the other side of the staircase, which was an open staircase by the way, was this small kitchen. The other room which would have been considered to be a parlour in the polite term in those days, was me fathers work shop. I remember he got permission to have, well he had gas mains laid on and in his workshop he had a gas engine running.

So that means you lived in the kitchen..

R- Well we lived in the living room downstairs, one room.

Well that's, you called that the kitchen didn't you.

R- Well you could call it a kitchen.

Yes, that's the triangular room you were talking about.

R- No that’s just off one side.

Oh I see, there's two rooms downstairs.

R- Yes.

So one of them is your fathers workshop.

R- Yes which was the remainder of the triangular portion.

Oh I see, that's it aye. Narthen which room did you have your meals in?

R- Well we had the common living room, the big living room where the fireplace was.

And where did your mother do the cooking?

R- It was in [that room] there was a big old-fashioned iron range.

That's an iron range with an oven and the side boiler?

R- Oven and side boiler yes.

Back boiler?

R- No back boiler no.

And where did your mother do the washing?

R- Well she did it in the kitchen such as it was with a dolly tub and posser and the old wringing machine.

No bathroom?

R- No bathroom, none whatever.

So where did you have a bath?

R- Well when we had a bath you put a tin bath down in front of the fire and had a bath when the others had gone to bed and vice versa.

Aye, what night Arthur?

R- Well invariably Friday nights.

Do you know, everybody had a bloody bath Friday night! [Arthur and Stanley laugh]

R- Well invariably I should say Friday night yes.

The lavatory, outside..?

R- Narthen here we are, now the houses in St. James Square, which are still there, although there was a demolition order on them two years ago, but I digress. They were back to back houses and funnily enough the houses which were the other side of ours, they had to come round into this common yard where there were three houses. There was our house number 7 and one next door, I forget the number and another, and there was a block of three lavatories, similar to what I described earlier on. The primitive type.

There were a block of three toilets there. Now those ud be dry toilets?

R- Those tubs.

That's it, tubs dry, that's it aye. Emptied once a week if you were lucky.

R- Two families joined to one toilet. There were six houses, three back to back. So there was three toilets and six families joined at three toilets.

That's it yes. So if you were lucky you got a clean family sharing at yours.

R- Yes, not too bad.

Aye that's it. And how were they emptied?

R- Oh, thereby hangs a tale. In those days, to be impolite, they used to come round on Mondays in our area anyway. Mind you it wasn't uncommon in the town in those days to be these dry lavatories as we might call them, and to be vulgar, the old shit cart used to come round Monday. And you can believe me all the bedroom windows were closed for quite a hell of a long way round.

(750)

R- And I can still remember 'em sprinkling pink powder, some sort of disinfectant stuff in the tubs. And never washed out. And it was a thing we grew to accept, never thought anything about it. Incidentally, the first flush toilet that I ever saw was when I went to an uncle at Manchester and I thought it was a bloody miracle.

And did your house have piped water?

(40 mins)

R - Yes. We did have piped water.

Cold water, no hot water system.

R- Yes.

That's it, and had you got a stair carpet?

R- No.

Wooden stairs or stone stairs.

R - Wooden stairs.

Aye it's an open staircase you said so didn't you.

R - Yes.

Can you remember if the neighbours had stair carpets?

R- I can only remember one neighbour that would have.

So would you say that, so you'd say that in that area stair carpets were probably uncommon.

R - Well I should say they were a luxury.

Yes that's it. How about floor coverings in the rest of the house?

R - Well floor covering. It was a stone floor and the best thing that we could afford in those days if I remember right was coconut matting which would cover a large amount of the floor. It had one fault it let all the damned dirt through underneath. And very often a home made peg rug in front of the fire.

Aye. Who made the peg rug?

R- Mother very often, but kids used to help an all.

(800)

Yes. How about curtains?

R- Well curtains, you had the usual lace curtains and whatever other curtains you could afford to buy.

Blinds?

R- Well very often made out of cotton from the factory. and dyed.

Were yours made out of cotton from the factory?

R - I think they were yes, and dyed.

How about upstairs, any floor coverings upstairs?

R- No, if we were lucky we got as one would say a threadbare rug that had served it’s best purposes downstairs. At the side of your bed just so you wouldn't have cold feet.

How about oilcloth?

R- I remember me mother’s room, mother and father’s room, being covered with oilcloth because at that house to go to my bedroom I had to go through mother’s and father’s. Distempered walls, there were no such luxury as wallpaper.

Aye that's it. Can you remember any families round about there not having curtains at all?

R – No. In spite of the poverty in the town a certain amount of pride and decorum. However they managed it, they did have some sort of covering for the windows.

Did they donkeystone the doorsteps?

R- Yes very much so. The yellow and the white and if I might digress, this is still whilst I’m living in St James Square. I'm sent to Blackburn every Saturday morning for lessons, music lessons, and I remember walking down the streets of Blackburn which would be a revelation to-day

(650)

because they vied with one another, the designs that could be put on the window cills and the door steps, and even on the pavement outside the houses. In those days, without exaggeration, you could have eaten your food off the floor because everybody swilled and scrubbed outside and donkey stoned. It was a pride, it was a thing that you, sort of a pride. Not that it was a great achievement but it was a sort of keeping up appearances.

That's it. I often tell the tale, I have been told, I don't know whether it's right or not but I can quite believe it, that there was one street in Ashton-under-Lyne where they even black leaded the tram lines.

R- That 1 can quite well believe.

And as I say I've no proof that it's right but I can believe it.

R- I could well believe it too because Lancashire people were very, very proud people.

Yes. Can you ever remember sand on the floor?

R- Well when it comes to sanded floors, the only sanded floors I remember is the Dog just down here.

Aye. Greyhound Hotel.

R- Yes, in a pub. It was quite common for a lot of the pubs that had stone floors, they were nearly always sanded and not only that but round the bar and at strategic points there was always these cuspidors or more commonly called spittoons.

(900) (45 mins)

That's it. And how was that house in St. James Square lit?

R- It was lit with gas because as I said father was a gas fitter.

Fantail or mantle?

R- Vertical mantles.

Aye, incandescent mantles.

R- Not only that but it was on a sort of a telescope tube, you could bring it lower or push it higher according to what you wanted to do. If you were sewing or as I said. Many a house had paraffin lamps. To go back round all Jepp Hill and all up that way, Orchard Street was all paraffin lamps. And as I said, anybody, eventually bit by bit they got gas in down stairs then when they could afford it they had gas upstairs . And I can remember when I was married at first and I got a house, I got a by-pass thingummy, so you didn't have to strike a match and light the gas. I could turn the gas on from the doorway to light the gas. Understand what I mean?

Yes. A pilot.

R- Yes, a pilot light on.

(950)

Yes, that ud be a marvellous bloody thing then.

R - But the first gas lights I remember in the bedroom was very similar to a Bunsen burner, a Bunsen burner and an acetylene lamp, which gave you this fanlight flame.

Fantail jet aye.

R- Very poor illumination.

SCG/07 May 2003

6,258 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 78/AL/02

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 17th OF SEPTEMBER 1978 AT HEY FARM, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS ARTHUR ENTWISTLE, RETIRED ENGINEER AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Now when did you first have electric light Arthur?

R - First have electric light? That would be 1935.

Ah, so that wouldn’t be at St. James Square?

R - No this was after I was married of course.

That's it, well we'll get round to that when we got round to your marriage. Now how did you dispose of the household rubbish in St. James Square?

R- Oh there was dustbins. Just let me get this right. We used to have what they call an ash pit not dustbins, and that was emptied periodically. It was, all the refuse was tipped into this, it was open front with a roof on this ash pit because the main heavy rubbish was the ashes from the fires. Cartons and paper of course was fired but empty tins, well when you think of it, tins of salmon were a luxury in those days so there wasn’t much rubbish like that. There’d be mainly ashes, coal ashes and things like that, that was rubbish.

So It ud be true to say that very little ud get thrown in the ash pit that would ever start smelling. Most of the stuff had been through the fire first.

R- More or less, yes.

Yes, and many a time, tell me if I'm wrong, many a time even the tins were put through the fire weren’t they.

R- Yes it's always been, and you may quote this, it's always been a habit of mine, even today. From the point of view of discouraging vermin and health hazards. I always have done, and I even remember me dad always burned empty tins when we were lucky enough to have salmon.

Yes, and apart from that, you know yourself, a tin either side of the fire hole makes the hole smaller doesn’t it, you can get by with a smaller fire.

R- Yes, that’s true.

I've seen that done in our house, you know, an A1 tall tin each side of the fire and it's amazing, it'll save half a shovel full of coal in a day. Aye. Now how did your mother do her washing?

R- Well, rubbing board, dolly tub, posser. The early posser was a thing with four legs on like a stool on a stilt which you twisted round and then later on there came conical shaped copper things with pipes threaded through which would then squirt the water different ways through the wash. In other words to get, force the dirt out of the clothes by the friction of the water. (These were used with an up and down motion) And of course the old wooden rollered wringing machine which invariably stood in the back yard in many cases with an old coat thrown over the top to protect it from the elements because they were a cumbersome thing.

How about, I nearly said washing powder! What did she use for washing? Did she use soap or..?

R- She used to use grated soap in the early days until the washing powders came on the market, say in the middle thirty's.

How long did it take her to do the washing?

R- A full day without question or doubt.

And how often did she do it?

R - Once a week.

And how did she dry it?

R - Well if it couldn't be dried outside it was dried inside on the maiden and then when it was sufficiently dry it was ironed and then put up on a rack which you wound up, long bars of wood..

That's it, in front of the fireplace on pulleys.

R- On pulleys yes, which was wound up and you’d hang your clothes there.

Would a rack like that be a luxury Arthur or would it be a fairly common thing in almost any house?

R- No I wouldn’t say it was a common thing in every house, if you had one that wound up on pulleys you see it was a luxury. Prior to that it was a piece of string hung across the fireplace and you put a few clothes on it with the risk of scorching or what have you. But the mantelpieces were fairly broad and fairly far out from the wall in many cases and that's how they got by.

What can you remember most clearly about washing day?

R- Well, most clearly, the personal discomfort in the home of wet clothes hanging about, irregular meals because when washing was in progress it was, well you take your bloody chance sort of thing.

Would Monday be the usual washing day?

R- Monday invariably was washing day.

(5 mins)

So dinner on Monday would be resurrections?

R- Well, come back to St James Square where there was a limited area there was a communal arrangement where Mrs So and So would wash on one day and Mrs So and So would wash on the other day so that the lines would be available for all the washing in the yard. It was a kind of a small, very small community arrangement which until the women fell out, which they invariably did, seemed to work successfully.

And how did your mother clean the house Arthur?

R- Clean the house. [laughs] Well I think today's modern woman would shudder. You had a stiff broom and I remember, as I remarked earlier on, you would have coconut matting and the floor was vigorously brushed with this stiff brush. Occasionally the mat would be rolled back and the muck underneath that would be brushed out through the doorway and out, into the back yard more often than not. Carpet sweeper, well until you got into a house with the luxury of a wooden floor and carpets, they were practically, virtually unknown and in the house that we were living in it wouldn’t have been a bit of use nor would a vacuum. Well a vacuum might have been but…

(100)

Now about furniture Arthur, can you remember anything about the furniture?

R- The furniture was always the hard bottomed hard backed kitchen chair. Sometimes bentwood chairs which have gone out of fashion. One always had a big square table with a white deal top, well scrubbed and of a Sunday of course you always had a cloth on it. During the week you would have had what we called an American cloth on it, it was a kind of, well..

Soft oil-cloth?

R- That’s right yes.

Yes, I know what you mean. Was there a sideboard?

R- We did have a sideboard yes.

Corner cupboard?

R – No, no corner cupboard.

Was there any piece of furniture that your mother particularly looked after? You know, that she was very particular about.

R - Well this again was at a different period of time. It seemed to me that we had the best furniture when me father was in the army. I remember we had a round table, a mahogany table with a velvet table cloth.

That's before you went into St James Square.

R - Yes that was while me father was in the army. But after that until we left St. James Square it was just what you might call good solid rough uncomfortable kitchen furniture.

Aye that’s a good description.

R - Well to give you an idea. I didn't have a seat. My sister and I, this was before the other two boys were born, was not allowed to sit at table, we stood up for our meals and when I wasn't playing out my seat was a coal bucket by the fireside with a sack on top of it.

Aye.

(150) )10 mins)

R- And when I started work I was allowed to sit down at the table.

We'll get on to that when we get on to meals Arthur. I'm very interested in that but we’ll get on to that when we get on to the meals. Did you or your brothers and sisters do any jobs in the house?

R- Oh yes, yes definitely. I must just point out here that there’s a discrepancy of twelve years between my other brothers and myself and my sister. One of my jobs, we had a steel fender round the fire, in front of the fire, and the usual fire irons, tongs and long poker and it was polished steel and my job was to brush the hearth, take the ashes out from underneath the fire, which was in a pit under the fire with a grate on top to let the finer ashes through. The other, the cinders, you used to shovel back on the fire. But anyway to come back to the fender, the method of cleaning it was a piece of rag, and you spit on it put it into the grit, the dust off the ashes, then scour the steel work of the fender and then polish it until you could see your face in it. Not only that, my mother and father were working and I were still at school so we had to wash up and lay the table ready for our parents coming home. Of course, chopping the fire wood, bringing the coal in and running the Sunday errands was all part of life we didn't question it.

Did your father do any work in the house, like mending things or decorating, cleaning, cooking or anything like that?

R - Well not regularly. I remember, we’re still, we're back in St. James Square when he came out of hospital, the military hospital before he was fit to work and mother was working he did cook the meals and I must say this, he was a very proficient cook at that which I believe he had learned whilst he was in the forces. But what he used to commonly call Mary Anning such as washing a floor, scrubbing a floor, no. He would make a meal and superintend me sister and meself doing other jobs in the house until he got fit enough to go to start work,

(200)

R - Oh he could cook, but after that, after he started work, we would never do anything in the house at all. It were what he called Mary-Anning.

When you lived in St. James Square did the family own that house?

R - No. Rented property.

Any idea what the rent was?

R- To be quite honest I haven’t. I think during the war years it was about 8/6d and then it went up I think to 10/-. (ten shillings)

When you say during the war years, do you mean the first world war?

R - Yes. The first world war.

How was the landlord?

R - That I don't know.

Did you ever hear your parents saying anything about him? Whether he was a good landlord or a bad one?

R- No I can't recollect they did. The only thing I might have heard them complain that he never did any decorating for you. You did all your own painting more often than not, white washing the rooms or distempering 'em according to your circumstances.

When you say decorating, do you mean inside or outside?

R - Inside and I remember outside, me dad did cement wash it every year.

Cement wash the stone work?

R - Cement wash the stone work.

Did your mother do any work in the house to earn a little bit extra money. You know like child minding or taking in washing or anything?

R- No I can’t remember her minding anybody else's child because she was always at work herself and I don't recollect, she wasn't a needlewoman.

Did she weave up till when she died Arthur?

R - Well I can't say up till she died. Lets say she wove until she left the town in 1940.

Yes of course, I'm sorry I was forgetting that. Were there any women in the neighbourhood doing anything in the home to make a bit of extra money, like taking in washing or mending, dressmaking.

(15 mins)

R - Yes very often some women neighbours, I can't specify who because it's a long time ago. Many of them would cook a meal in their own home and have it ready for a neighbour and was paid for doing it. So that they had a hot meal when they came in from work.

Good idea too.

R - And I had an aunty who was very, very skilful at crocheting and needlework and so was popular and so good that she could knock quite a bit of money up at it.

(250)

R- Course in those days interior decorations, the fireplace being the focal point in the house, eventually instead of just having the iron mantelpiece they started off with having a board put on top. Extending it and deepening it, and then having it curved. And very often either they would have a velvet pelmet as we would call it today or more often than not it was needlework, made in kind of like a green hard linen type of stuff, hard wearing. And she could knock up quite a bob or two on that. And she even crochet and knit baby’s shawls and that sort of thing and made herself quite a bit of money.

What did your mother cook on?

R- Well we had the old fashioned range, oven. More often than not in those days it was pans on the top bars as we called it. The kettle was on a swinging iron above the fireplace, swung away if it wasn't needed. I remember the main diet in those days was hashes, stews and that. In my days, what I used to consider to be a luxury was plum duff.

Aye, we'll get on to plum duff in a minute or two. When did your mother have her first gas stove?

R- Now then.

That's a difficult question actually I know.

R- First gas stove, I’m just trying to get, she had her first gas stove, oven when she left St James Square and went to live in Lower North Avenue.

So all the time you were in St. James Square it was..?

R- Open fire and an oven.

Open fire. Reight Arthur. Did she bake her own bread?

R- Yes.

And how often did she bake?

R- Sometimes twice a week.

And did she bake cake. When you say twice a week, she didn’t bake, well obviously I was just going to ask a silly question then. I was going to ask you if she baked enough for all week when she was baking twice a week. I'll forget that question Arthur. Did she bake cake?

R - Well what one would call today oven-bottom cakes, sad cakes, currant cakes.

(300)

How about fruit loaf, sweet loaf?

R- Very rarely, they were luxury.

You see that’s a striking thing, well I say striking, that’s a small thing that nowadays, when we talk about cake we mean what you and Amy, that’s your wife of course, that's for the tape because they don’t know that your wife's called Amy yet, would call sweet loaf and fruit loaf.

R - No when I say cakes I mean what were commonly called sad cakes. Unleavened some people would say.

That’s it, oven-bottom cakes, sad cakes.

R - Some with currants in and some plain. And the sad cake we used to eat warm from the oven, quarter it, slice it down the middle and put margarine or butter as the case may be. And we used to eat them warm.

Did she ever make it with mint in?

R - No not to my knowledge.

It's nice with mint in. Did she make pies?

R- Oh good lord yes. She was renowned for making pies.

What kind?

R - Meat pies and meat and potato pies.

And sometimes if things were bad, just tattie and onion?

R - Very often, sometimes a little bit of corned beef which was a cheap form of food in those days.

Did she make jam or marmalade?

R - Not very often, not very often.

If she did, did your mother have a jam pan?

R- I don't think she did as such. If she made jam of course cast iron pans would range from, I won't say quite enormous, but largish pans down to what we called milk pans.

(20 mins)

Yes.

R - So there was no such thing as a proper jam pan as we know today. Brass or copper.

Did she make home made wine or beer?

R - No never.

Pickles?

R - No not to my knowledge.

Did she ever make any of her own medicine?

R- Well, if you can call it medicine. Yes she would make a kind of medicine where she combined sulphur, thick black Spanish and some sort of evil concoction when you had a cold or whatever, it sort of cured all, kill or cure.

Well as far as your mother was concerned that was medicine, she was making her own medicine, yes that's it.

(350)

R- It was medicine yes.

And how about sulphur and black treacle. Brimstone and treacle?

R- Brimstone and black treacle. That was a common thing in the Spring. If you got a bit spotty or something like that.

You know my mother was the same, she had this idea that sulphur cured spots. It did something to your blood, purified the blood.

R- That’s right purify, that's it.

You could get sulphur tablets couldn't you. Do you remember them? You used to suck them. Ernie Roberts tells a good tale about that, about his mother dosing him with flowers of sulphur for tonsillitis and the way she did it, she put it in a tube and blew it down his throat, and be blew first so there you are.

R – (Arthur laughs] Coming back to home, what you might term home remedies. Of course in those days I didn't know a lot about those sort of things myself, but I can remember amongst the women, Senna pods was a universal must to make sure that they had their menstrual periods. There was a firm belief in Senna pods too if they thought they were pregnant. If they missed a week it was always Senna pods or a strong brew of Senna pod tea.

Have you ever come across Penny Royal?

R- Now then, this is only vaguely in my mind. I’ve heard the name but I can’t remember. I’m not going to honestly say that I knew of it at all. I've heard of it.

I've been told that penny royal, I've no knowledge of this, I haven’t gone in to it. But I’ve been told that penny royal was a herb which was supposed to be of value in inducing an abortion.

R- You've jogged my memory. That's where I may have heard of it listening to women talk. You know as you were a kid, well they think you're a kid, you have big ears and you hear a lot of things you're not supposed to do. As I say I'd heard of penny royal but didn't connect anything until you've just mentioned it now.

Yes, well that make it suspect. Now you were mentioning earlier on about the lady that got sent to Strangeways.

(401)

Would that be a fairly common thing in those days. I mean obviously a lot of women would be frightened of pregnancy wouldn't they. They were in such, there was such poverty. Was it fairly common, abortion?

R- It was, it was quite common. I'd go as far as to say it was common even in the late thirties. Not as common as it had been, because married women invariably, as far as my aunt goes that was sent to Strangeways, it was invariably unmarried women or in some cases during the war, where their husband had been away on service and it couldn’t possibly have been, you understand what I mean? And then they went for help for creating an abortion. She did it manually, I can't say just exactly how but as far as 1 can remember it was sort of if you could prick or puncture the womb it would bring about an abortion. But of course where so many young women died was by the lack of the proper high sterilised equipment, if you follow what I mean. And there were certainly a lot of young women did lose their lives by it. That's why the law was so strict and they jumped down heavily on women that were known to abort people. As I say she got many a woman out of trouble in this town and then of course when she went to prison nobody knew her. But she lived it down you see. A sort of nine days wonder.

(25 mins) (450)

What did you usually have for breakfast Arthur? Straight from abortions to breakfast Arthur.

R- Porridge on some occasions, toast on some occasions. Bread an jam invariably and this, I might emphasise on this, the only time one saw an egg was on a Sunday and until I got working my sister and I shared an egg. If it was boiled it was hard boiled, cut exactly in two and we had half an egg each. Or if it was fried in the frying pan it was turned over and we had half an egg each. It wasn't until I got working or started apprenticeship that I was allowed to have a full egg. Then of course my sister had to have a full one, because there wasn't anybody to cut in half with if you follow what I mean.

Aye it ud he a good thing for her wouldn't it. [both laugh]

R - Yes and then I was allowed to sit down at the table.

Yes now you were saying about this. Now you've mentioned one or two things that are starting, to knit together. Now we've got the big square wooden table with a scrubbed top, you've said that on occasions there was American cloth on it.

R- More often during the week.

Yes that’s it. Now at weekend, what was there on the table.

R- Well you’d have, I don't know whether I'd call it linen but it was, it had a design woven into it type of thing.

Tablecloth.

R- Tablecloth.

Yes. Now when you had a meal, during the week we're talking about now, did all the family have the meal at the same time?

R- Always unless [someone was working].

Did all the family sit down?

R- No, not until I got working.

Did any of the family get to sit at the table before they started working?

R- No.

Did everybody at the table have the same things to eat?

R- More or less yes. Apart from, as I say, when you come to the egg and you only had a half.

Yes.

R- But apart from that if it were, well mussels and cockles or

(500)

fish and chips or hash, stew or whatever it was, we all had the same sort of food.

On the whole would you say your fathers diet, and the food he ate, was it better or worse than yours or just about the same?

R- Just be about the same, only the quantities would be different.

Yes. And did the family have a garden or an allotment?

R- Oh no, not at that time.

But later on?

R - Well later on the old man had a hen pen down the Butts where he had a few fowl and goats.

And did he use the produce himself or did he sell any.

R- Used it domestically.

Yes that's it.

He reared young goats and when they were old enough he’d slaughter them and we’d eat them in the family. When I say the family, I mean uncles, aunties.

Did he slaughter the goats?

R- Oh yes. He used to bring ‘em home, bring them into the bathroom the young goat…

Into the…?

R- Into the house..

Yes, you said bathroom.

R- This is when we were in Lower North Avenue when we’d moved up just as I said. And of course he’d use the bathroom as a slaughterhouse, the animal in the bath until it bled and then it was skinned and cut up and uncles and various relatives had portions of it because you'd no means of keeping it you see. But I will say this, people today would look down their nose on it but I’ll say this, it was far superior to any of the best lamb you could possibly buy today.

This was Goat meat?

R- Goat flesh.

And what year would that be about Arthur?

R- Let's see, 1926 or 1927. Thereabouts.

1926 or 1927, aye just about when your dad finished for the railway.

R- Yes.

How much milk did the family get each day?

R- Narthen. I couldn’t say with certainty, because milk was relatively cheap. I could safely say it ‘ud be a minimum of a pint a day.

Yes.

R- A minimum.

How often was it delivered?

R- Morning and evening.

And how was it delivered?

R- Well horse and cart, kits and boys with little cans with the correct measure came into your house and poured it into a jug and then back to the cart, get it filled up and deliver it next door, the milk boys.

And did the family have butter, did your mother use butter?

R- Not very often. It was more often than not margarine.

How about dripping?

R- And dripping.

What fruit did you eat most often?

R- Well, I should say if we did have any fruit as a luxury it more often tin pears and things like that.

Aye, and how about fresh fruit?

R- Very little unless what you bought when you was going to school, that sort of thing.

Now there's a thing, you don't eat fruit do you?

R- I don't now but I did until I was fifteen.

Yes, what changed you Arthur?

R- Well I don't know, it's something psychological I think. Down Frank Street there was a big greengrocer’s shop and fruiterers and what have you. Not only was he retail he was wholesale and there must have been fruit gone bad and I know I was passing this place one day and I must have got a real lung full of this. What I would call a stench and today the very smell of fruit puts me off. I don’t know why, something psychological. I can’t really explain it.

Well we're not in the business of explaining, no, that's all right Arthur.

(600)

Now I’ll just mention a few foods here and just tell me if you had them, every week or once a month or very rarely or never. Bananas?

R- Bananas, sometimes we’d have them on Sunday as a dessert at tea-time after a meal of sandwiches and what have you, with skimmed milk on. Cream was virtually unknown. Bananas sliced up you know with milk, tinned milk and sugar.

[Arthur means evaporated skimmed milk when he says skimmed milk. It was a cheap alternative to cream]

If you had bananas with the skimmed milk and the sugar would it be usual to have bread and butter with it as well?

R- Yes I’ve know me sister and I've seen me dad make sandwiches out of 'em.

How about rabbit?

R- Well I wouldn't say every week, but if I said twice a month that we had rabbit pie I wouldn't be far wrong.

Where did the rabbit come from?

R- My uncle was a poacher.

Oh there was a lot went on! How about fried food, out of the frying pan Arthur?

R- Fried food, well apart from bacon, kippers, the occasional Haddocks something like that there was not much fried food.

Any other sort of fish?

R- I’ll tell you, well I’m telling a lie when I say there wasn't.

(35 mins)

One would have what we called bubble and squeak. In other words what we didn’t finish at Sunday dinner in the way of cabbage and potatoes and what have you was all chopped up and put in the frying pan and fat with it. And believe you me you can make a bloody good meal out of it with a slice of bread.

Aye, I've eaten it myself. Did your mother used to fry it until it went brown on the bottom or did she just...

R- Yes more or less when it was just starting to stick to the pan and that was it.

Just started to stick to the pan and that were it aye. Me mother were the same. Fish Arthur, apart from, you mentioned kippers and a bit of haddock fried you know. Did you ever have fish in any other way?

(650)

R - No.

We’re including shell fish of course.

R - Only the Finnan Haddock boiled, it was invariably boiled.

Yes with milk.

R- That's about all.

Yes, and you've mentioned cockles and mussels..

R – Well, Cockles and mussels.

Yes that's it.

R - In season of course.

Is there a season for cockles and mussels?

R – Yes.

Well do you know I didn’t know that Arthur.

R- Yes.

Well that's happen why I've been so poorly off 'em from time to time. Cheese?

R- Well there again I never ate cheese. Although there was cheese in the house.

Any particular reason why you didn't eat it or you just didn’t like it?

R- Well as I said it dates back to this psychological thing about smell. Now if I don't like the smell of anything I couldn't eat it to save me life. I couldn't sit down and eat a curry even though it might be delectable. But I just couldn’t and it's always been the same with vinegar or sauce even. The smell disagrees with me so I couldn't face it.

How about cow heel?

R - Oh yes cow heel.

Tripe, trotters, black pudding?

R - Tripe, trotters, black pudding, yes.

Great stuff.

R - Coming to black pudding. If I may just emphasise one little point here I don’t know why it was, but it was sort of a family custom in my father’s family and how long it went back I don't know, but Christmas Day breakfast was always nothing else but black pudding and bread.

Yes. Was it fried or boiled?

R - Fried.

Yes I like it fried. Eggs, well you've told us about eggs haven't you. They were a luxury. Tomatoes?

(700)

R - Never eat them.

Grapefruit?

R - Oh grapefruit wasn’t, at that time you're speaking of I don't think it had been cultivated.

Sheep’s head?

R - Very often.

Very often.

R- It was my mothers favourite. Sheep’s head with, I’m trying to think of it.

Lentils?

R - Not lentils, it’s another, is it barley?

Pearl barley?

R - Pearl barley.

Yes.

R – She’d sit and pick at a sheep’s head for hours.

Did your family ever had tinned food?

R- Occasionally, as I say high days and holidays you'd have tinned salmon, something like that.

Corned beef?

R- Corned beef. Oh corned beef very often was taken to work for sandwiches, in between your sandwiches. For dinner time, lunch time.

Yes. Can you ever remember tinned food being bad?

R- Being bad?

Yes.

R- No I can't say. I can't say honestly that I do.

Aye. Did the family drink tea?

R- Tea yes.

Cocoa.

R- Cocoa often yes.

Coffee?

R- Coffee, never.

Never. When you say never, why, price?

R- Well it might have been price or it might have been parents preference I don't know.

What did you have for Christmas dinner?

(750) (40 mins)

R- Now then, we’d either have a big hen, I never knew the luxury of a, I think once we did have a goose but never turkey. Sometimes a duck, but when there was a family of six of us, when me other two brothers were born, of course we used to get a good big fat hen or a couple of cock chickens you know. Enough to feed the family for that one meal. Same as the way today, as you know yourself, they get a turkey at Christmas and the damn things kicking about in the New Year if you're not careful if there's a small family.

That’s it aye. Christmas pudding?

R- Always.

Always. What were your favourite foods when you were a child?

R- Favourite foods?

Yes.

R- Well my favourite food was meat and potato pie or pie and peas.

[Stanley laughs] It figures Arthur! What did you have to eat when the family was particularly hard up?

R- Ah, now then. Well it was more often bread and scrat as my mother called it. Bread and scrat which were dripping. Or bread and margarine and invariably jam like.

I must just say it while I think Arthur. As you know in many ways we've had similar setting offs in life. If you had bread and dripping did you ever get the luxury of pepper on it?

R - Salt.

Never pepper?

R- Not often, because I’ve never been a lover of pepper individually.

Aye that's it yes. You see I forget. But was it there if you wanted it, was it there?

R - Oh it was there if you wanted it yes.

Would you say that pepper was a fairly cheap spice, would nearly everybody have it?

R- I don't think it was a cheap spice in those days, a more common thing that was used, we had often on a Sunday, which you haven't mentioned or asked me, if I might butt this in. Invariably we’d have a milk pudding, rice pudding on a Sunday and I always remember me mother having a nutmeg and a grater and sprinkling lavishly nutmeg on the top of the pudding.

It makes you wonder if she’d have done it if she'd have known. I mean they say now a days that nutmeg is an aphrodisiac. It makes you wonder if your mother ud have been sprinkling nutmeg on.

R - [Arthur laughs] I don't know..

It is one theory..

R - Is it really,

It's reckoned to be a fairly potent drug nutmeg you know.

R- Oh, I didn't know that.

Yes. I can believe it an all, it tastes very strong doesn’t it. And it certainly does warm your stomach up. Did your father come home for all his meals?

R- Put it this way, if he wasn’t on a boozing session yes.

Oh good, that'll come in later. If not, if he didn't, well you’ve just said that he did, but can you remember him, you know, actually saying that he wasn't coming home and taking something to work with him?

(850)

R- Well can I re-cap back to when he started work on the railway. Very often he used to have to take a basin. When he worked on the railways it wasn't always possible to come home because he worked what would be called shift system today, there was an early turn and a late turn. First of all he was in the goods yard and very often I used to have to take his dinner down, it was done in a basin with a plate on top, rag round it. And you'd to go like hell down to the station yard to make sure he got his dinner hot enough so you didn't get your ear hole boxed. But apart from that, that’s just a case when he couldn’t get home for meals due to his occupation, otherwise he came home to all his meals, more or less.

Aye. How often would you say you took his grub down for him?

R- Oh, two to three times a week at least.

Do you think your mother ever went short of food to feed the rest of you?

R- Yes.

You're sure about that?

R- I'm sure about that.

What makes you so sure?

R - Well, it’s only in the light of later years that you think about these things and I remember sitting down, my sister and I sitting down to a meal and mother not sitting down to with us. Of course in those days, one assumed that she'd had her meal, which I suppose she probably intended us to think. But in later years I realised that she didn’t have a meal to feed us.

Yes. Who usually did the shopping?

(45 mins) (900)

R - Oh mother always did the shopping.

Yes.

R- Unless she sent us kids on an errand.

Yes. How often was it done?

R- Well in those days you'd to give your order into the shop which isn’t done to-day and it would be delivered to the house. You know more often than not I think we had food delivered to the house.

Yes, where were the vegetables bought Arthur?

R- At Savages.

Aye it figures, and where was the meat bought?

R- More often than not the frozen meat shop.

Dewhursts?

R - The Argentine.

Yes the Argentine, Dewhursts aye. And of course in those days it was the poorest people that went to the what they called 'Frozen' shop wasn’t it?

(950)

R- Aye definitely yes.

Yes. Where were the groceries bought?

R- Well, where the swap shop is now there was a very big grocer. (Corner of Frank Street and Rainhall Road. In 2013 it is the Co-op chemists) I think his name was Singleton. I always remember that shop because he had a poster in the window of fried eggs with lashings of pepper on the top, you know, succulent looking. And the shop it sold everything type of thing, from butter out of a tub or margarine out of the box and the..

Just one little thing there now, that's something that's not been mentioned, butter out of a tub.

R - Out of a tub yes.

That’s it and it's, well the barrel's been lined with paper and then filled with butter hasn't it they used to break the barrel away from it.

R - Yes. They'd take the lid off, start there and then they'd break a couple of staves off. Serve down to that level and then they'd take the other staves off until you get down to the bottom of the butter. By that time then, if it wasn’t a shop that had a big turnover, it was getting a little bit worse for wear as one might term it.

(1000)

SCG/07 May 2003

6,500 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 78/AL/03

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 18th OF SEPTEMBER 1978 AT HEY FARM, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS ARTHUR ENTWISTLE, RETIRED ENGINEER AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Right we're back on the ball again Arthur. We were talking about groceries and what not last night and if you remember you were saying that you got your groceries at Singletons.

[Barrett’s Directory for 1902 shows Thomas Singleton as grocer of Brook Street.]

R- Yes. Family grocers.

Did your mother ever shop at the Co-op?

R- No not as a regular member of the Co-op, no.

She wasn't a member of the Co-op?

R- She could possibly have popped in and bought some item that, like you do today in a supermarket, that was on offer or something like that, but I don't remember her being a co-op member as such.

Would you say there was any difference between the prices in the little shops on the street corner and the shops in the middle of Barlick?

R – No I wouldn't say there was any marked difference because food in those days was plentiful, what was lacking was money. There wasn't much undercutting as we know today or offers of cheaper goods, five pence off, you understand what I mean. I should say the price of the commodities in the shops, food wise, apart from the difference of the frozen meat and fresh meat, was pretty static.

Yes. Did the shops that your mother used use to give credit?

R- Yes.

Do you think she ever used that?

R- She definitely did, you got your groceries one week and you paid for them the next.

Yes, and how was that worked, what were the actual mechanics of that at the shop?

R - Well the actual mechanics were, if the shop keeper knew you, knew your family, knew you were substantial enough or could be relied on, you had a weeks credit.

Did your mother have a regular book at one shop?

R- Yes she had a regular book at this Singletons.

Yes that's it, because that's why they used to call it, the shop book, wasn’t it.

R- Yes.

How about pawn shops Arthur?

R- Ah well, there you are. There were a time when the term used to be pop in on Friday and pop back in on Monday, in other words you popped your wedding ring or sometimes your husband’s best suit, brought it out for week-end and it went back in on Monday if you follow what I mean.

(50)

That's it aye. Which were the pawn shop in Barlick?

R- Well, there’s a firm left in Skipton now, Ledgard & Wynn used to be in the middle of Church street where the Magic Eye is now, that was the pawn shop. Not only was it a pawn shop as such, it sold goods. Suits, linoleum, you name it, it was a typical Jewish concern.

Aye. you say Ledgard & Wynn?

[Though confused about Barlick, Arthur was actually right about Ledgard and Wynn’s. Horace Thornton {79/AD/02, page 15.} said that they were originally pawnbrokers in Skipton. I have no evidence as yet of them operating in Barlick.]

R - No I beg your pardon. There was two brothers in the town, there was Isaac and Louis Levi. One brother had a shop on one side of the street and next to the Commercial Inn, is it on the other side of the street, was the other brother. But they both sold furniture and one was a pawn shop, plus selling cheap, very inferior suits, you know what I mean. In other words you pawned your watch and you get a suit and you got fleeced both ends of the stick. You get what I mean, they were shoddy goods.

(5 mins)

R- I think they had a term for it in America, the company store which, well it's hardly relevant to this conversation but it was prevalent in this county a hundred and forty years ago. You worked for a firm and the firm paid you in their money and there's still some of that money knocking about in Dudley and round there.

Aye that's it, bucket shops.

R- That's right.

Aye, Can you remember if pawn shops did good business then?

R- Definitely, they definitely did good business.

Yes. Did your mother use them?

R- Infrequently if times were bad enough or there was a domestic crisis, sickness, if your husband hadn't a wage. I mean to say there wasn't the social security, you popped your wedding ring or anything in other words to raise a bit of money until times brightened up a bit.

Yes. Was there anything that you ate then when you were young that you can't get now? Can you think of anything that you used to eat then that you can't get now?

R - Well the commonest commodity that we ate in those days was probably what I call, even with the bakers, home baked bread which of course the combines have ruined today. Food in general, lots of it, you could get more than you can get today. Particularly in rice and cereals and things like that because today the eastern countries, it’s their main diet and there isn't as much of that sort of stuff coming into the country. There were split peas, fine peas and black peas, well you can't buy black peas today, not to my knowledge anyway.

Yes. Would you say food was short during the first world war?

R - Definitely it was short during the first world war. Not only was it short, the first few weeks, or the first few months of the war, before the Government got organised, in our family my father volunteered I think it was the second day of the war, and free flour, sugar. tea and the barest necessities of life, life which you can make your own bread and so on, were distributed in I think it's the Commercial Yard. You know when you get to the bottom of Manchester Road there's a boutique shop, then there's a pub yard.

The Seven Stars.

R- Seven Stars. Well in the Seven Stars yard. Soldier's wives who hadn't got their pay book could go there if they had definite proof their husband was in the army. I can remember the chap who was in charge was up that flight of steps, standing above the crowd, then you had a ticket given which entitled you to a certain amount of flour, sugar, according to the number in the family which in that day there was three of us, me and my sister and mother. And that was of course in [force] until the regular pay cheques became fluent through the war ministry getting organised shall we say. Food was scarce, you were at the mercy of every tradesman. Saturday morning the Maypole, margarine shop at the bottom of Frank Street, used to open from eleven o'clock till twelve and you stood in a queue probably from nine o'clock till the shop doors opened and according to the speed and efficiency of the assistants in the shop, which they treated you like dirt, you understand what I mean, because you were subject to their whim. ‘Well I’ll serve you if I want to serve you.’ you know. If you haven't got the right money, go and get the right money. You had to have the right money in your hand for what you was buying. And that also was when the coupons, the food coupons were issued. You had to take your food coupons to cover the amount of margarine you could buy. But as I said, the shops only opened, some shops only opened for a limited time.

(150) 10 mins)

Was it common to see queues at the shops?

R - Oh good lord yes. It was as common to see queues in the 14/18 war as it was to see it in this last war.

Did you think that on the whole the family was better fed during the first world war than before?

R- Er no, I wouldn’t think so if I can remember rightly even though when things got on a level keel, when I say a level keel, mother was drawing the army pay regular, she was also working. Food was scarce, but what we did get was good, what we did have was good honest food but it was no more plentiful than it was before the war.

That's it aye. Now then clothing. You've always been a natty dresser Arthur, did your mother make any of the family’s clothes?

R - When we were children yes. Of course at that time ours was a relatively small family but very often you'd have a pair of pants made out of some of your dad's old uns. And in families where there was at least six children, it was a case of hand me down from one to the other until they was absolutely thoroughly worn out.

Did she have a sewing machine?

R- Sewing machine, I can't remember my mother ever having a sewing machine, it was all hand stitched.

Did she mend the clothes?

R - Oh yes definitely.

And did you ever have any passed on clothes?

R - Patched?

Passed on, hand me downs?

R- Very occasionally.

Yes of course, with you being the eldest they'd have to be from somebody else's family.

R - It ud be out of some other member of the family like an uncle, older cousin for instance.

Yes. If your clothes were, you know, if your mother ever bought you any clothes, where did she buy them from Arthur?

R- Well in that day it was prevalent to run a system was in existence called clothing clubs. You’d have a fella called on a Friday night which was, I think I mentioned earlier, Friday night was pay night for all the little debt-collectors to come and collect the money whatever it may be, and the clothing club was one of them. And you paid your weekly payments of money and when you'd saved so much you got your clothing club check which there were certain shops accepted them. Sometimes we had to go to Earby, sometimes we had to go to Colne depending on the type of commodity one wanted. And there was always a suspicion in the minds of the working people of that day, that because it was a clothing club check, and yet it was ready money, they foisted on to you if they could inferior goods at the top price. So when you went to buy with a clothing club check it was the custom to pick whatever you wanted, try it on and say we'll have that and then smartly whip the check across. And this brought a very queer expression on the shop-keeper’s face, it was a case of being outsmarted. But later on after the war, I'm running over a little bit, they became what they called the Scotchmen. In other words tailors came from Nelson and Burnley, Colne.

(200)

Narthen that's interesting, I've heard that before now. I was told that before, that the Scotchmen was just a slang term for the bloke that was collecting for the Provident or whoever it were.