TAPE 79/SD/01

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON AUGUST 14TH 1979 AT 26 HARGREAVES DRIVE, RAWTENSTALL. THE INFORMANT IS JIM RILEY, MULE SPINNER AT SPRING VALE MILL. THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

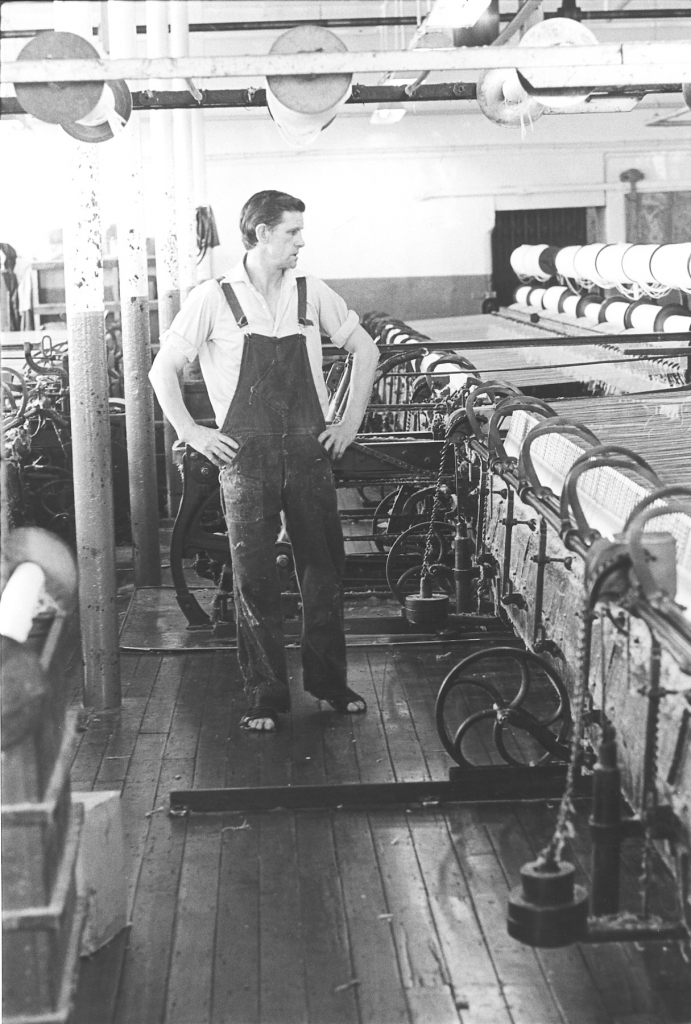

Jim Riley in the wheelgate at Spring Vale.

Now then Jim, how old are you?

R- Forty eight.

So you were born in 1930 ... 1931?

R – August 1931.

Now, where were you born?

R- Loveclough.

Loveclough. That’s just up the road here, between here and Burnley.

R- Just that village between Burnley and here.

What was the street, what were the name of the street?

R- Broad Ing Terrace.

What were the name of it?

R- Broad Ing Terrace.

How do you spell that Jim?

R- Broading, B r o a d i n g. Broading Terrace.

Aye. Broading Terrace. That’s it aye. And how many years did you live in that house?

R- About four, four or five years.

And where did you move to then?

R- Just further up the road, on what they call Burnley Road, the next row.

Yes. What were the reasons for that move? Do you know?

R- Well, when we lived at Broading, we lived in what they had cellars underneath you see. Well, they were going to shut them down you see so they moved them out, and we moved farther up, on Burnley Road.

So they were going to demolish them?.

(50)

R- No, they were going to close the cellars down. They are still there actually, oh aye, those cellars.

Yes. And were you living in a cellar?

R- yes we were. We were born under them cellars you know.

So you were living in part of a house then were you?

R- Yes. Houses on top and these cellars were underneath, you see. And I were born under there. And then they come to close them down so then we moved up on to the row further up.

Yes. Tell me Jim, was that like these houses in Hebden Bridge, was it like one house on top of the other, and you went into one from the top of the hill side, and went into the other from the bottom?

Castle View in Barnoldswick. These are similar houses to the ones Jim describes, a two storey house accessed from the street at a higher level than the two-roomed cellar dwellings below.

R- That's right, yes.

And they decided they were substandard, did they?

R- Yes, so they moved us, we moved out.

And they were going to move you out? Well, how…

R- I were only small then, you know. I were only little, right little like.

(100)

Yes that’s it. So you moved out of them when you were. How long were you living in the other house on Burnley Road?

R - Oh ... nearly all the time I lived up there.

Which would be how long, Jim?

R - Well up to moving down here in 1966. I lived at that row all the time then.

Right, that's a good do. Right, well the questions that I'll ask you, I'll be asking you a lot of questions about the house then that you lived in when you were young. And I'll be talking about the house on Burnley Road. But before I do, tell me what you know about the houses on Broading Terrace, you know, the ones that were the cellar houses, what can you remember about them?

(100)

R- Not a right lot, n. ‘Cause I were only a little un you know…

No. That's it, yes. Now what do you know about them, because you'd see them again afterwards?

R- Well, you see, when I got married to the wife we went living in a house over the top of them cellars where I were born you see? And the house that we lived in up over the over the top, it were our underneath you see, and there’s the house. as I were born in. And there were only two rooms in it. Just a living room and a back room For, it were a bedroom.

And the back room couldn't have any windows.

R - No. A bit of a grating.

That*s it, a grate that came up from the front of ...

R- On to the front of the landing, on to the front of the landing.

That's it, just the same as those at Hebden Bridge. Yes, that's it aye.

R- Just the same, yes. And they were very, very dark. And at the front door, what were the front door, were a big, high wall you know, and there were just one window and it were very dark. And they had gas in you know.

(5 min)

So moving up to Burnley Road, it'd be a big improvement for you.

R- Oh yes. Yes well there were electric in.

Yes, well, I'll be asking you some questions about houses, like. I'll ask you about Burnley Road. Now then have you any idea where your father was born.

R- Eh I don’t.

No. What was your father's name. Jim?

R- William Riley.

William Riley. Where was your mother born.

R- She was born in Padiham, me mother.

In Padiham yes, what was her name.

R- but she isn’t living now, me mother.

Yes. What was…

R- She were called Cook, Bertha Cook she were called before she were married.

Bertha Cook yes. And how many brothers and sisters did you have?

R - I had one sister. She died in 1960. 71. (Mother I think] Our Marion, she died of fits, she had epileptic fits. And I have a brother 18 months younger than me, he’s living now. He is living with me father.

(150)

Yes. Were they the only children that was, that were born? What I'm getting at, did your mother just have three confinements and she had three children?

R - No she lost two.

She lost two. Yes.

R- She lost two yes.

At birth?

R - Yes.

Have you any idea what that were with, Jim?

R- I've no idea.

No. That was very common of course wasn't it? And where did you come in the family?

R- Third. She lost two and then .. oh no, sorry, I come fourth, she lost two then our Marion were born and then me and then our Jack.

Yes, that's it aye. Can you remember what your father, do you know what your father’s job was.

R - Yes, he worked at C.P.A. Calico Printers Association, at C.P.A. that's down at the bottom of the hill.

Yes, at Loveclough here, yes.

The dye works at Loveclough in 1979. The new building going up in the foreground is the working men's club Jim talks about.

R- He was .. he worked in the colour shop, he were a colour mixer, mixing colour. He had a good job there yes.

Mixing colour .. aye, it's a responsible job that. Skilled job and all.

R- Yes, he did, he did it for years. Yes

And what did your mother do? Did she work at a1l?

R- She didn't work didn't me mother no. Not when, all the time I were about.

Have any idea if she had worked before she was married?

R - I think she were a weaver before she were married.

Yes. And that’d be at Padiham?

R - Padiham, yes.

Have you any idea how your mother came to meet your father? Did you ever hear her say anything?

R- No.

Can you remember any relatives living with you when you were a child?

R- No.

Any lodgers?

R- No.

How old, was your dad when he died?

R- How old was me dad when?

He died.

R- Me dad’s still living.

Oh is your father still living? Sorry Jim.

R- yes, I said me mother died but my father’s still living.

(200)

He’ll be a fair age then.

R- He’s 76.

Seventy six. Aye.

R- He is living with me brother

Yes, that’s it.

R- But he is not married, so he's living with me dad yes.

And how old was your mother when she died.

R – Fifty eight.

Did any of the family leave the area when they grew up, or did they all stay in the area?

R - No, they all stayed in the area.

All stayed in the area. Aye. Now, well we'll talk a bit about the house Jim. And now we are talking about that house in Burnley Road ...

R - Burnley Road, yes.

Because obviously a four year old, he won't be able to remember much about the other.

R – No, I didn't remember a right lot of that one now.

How many bedrooms did that house have?

R- Two.

And what other rooms were there?

R- Well, there were two bedrooms, a living room, a front room, and a little kitchen.

Now, what sort of furniture, can you remember any of the furniture at all, in any of the rooms?

R- Just, like, a three piece suite, there were one of the old fashioned big wardrobes, with a big mirror in.

Aye, in the bedroom?

R- Which were, which were common them days you know? And a dining room suite and that's all, more or less.

What did you use the front room for?

R- For guests really, you know. For people what visited.

High days and holidays?

R- Yes.

Aye. You'd be in trouble if you went in there during the week wouldn’t you?

R - Oh yes. That were kept clean were that so you hadn’t to go in there.

Yes. I thought it happened so. Aye. Which room did you have your meals in, Jim?

R- We had them in the kitchen, in the house.

Yes. That's, when you say in the kitchen, that's not in the little kitchen, that’s in the living room is it? Or do you mean in the kitchen?

R- Well in the kitchen just weren't big enough for us all to sit in so we probably had them in the living roomy you know? Yes.

Yes, that's it. Aye. And where did your mother do the cooking? In the little room at the back?

R – Yes in the kitchen yes.

(10 min)(250)

Yes that's it. Where did she do the washing?

R- In the cellar underneath. They had a stair, they had cellars underneath.

Aye. And did it have a bathroom?

R- No. They had the old tin bath

Hung outside the door?

R - That were in the cellar were the big tin bath, and we used to fetch it up and put it in front of the fire and fill it up you know with the hot water.

Aye. When were that Jim? When did you get a bath?

R- Once or twice a week . Well, used to be Friday more or less. You know, a big day.

That’s it. Everybody had a bath on Friday I think, everybody I've recorded except one, used to have a bath on Friday. Was it an inside lavatory?

R- No, outside.

It was outside. Was it flushed, tippler, or dry?

R- Tippler.

Tippler. Yes. Did you have piped water in the house?

R- Yes.

Did you have hot and cold, or just cold?

R- No, just cold.

Just cold. What did you do for hot water?

R- We used to boil pans, and the kettle.

Did your mother ever have a side boiler?

R- Yes. One of them big boilers you know. She used to boil it up with the gas pipe. We used to have a big boiler, with a pipe from, what led to the gas.

Aye. One of them Burcos with the gas underneath, galvanised round thing with three legs.

R- Yes. She used to have one of them yes.

On four legs? Four legs they had.

R- Aye, big uns they were.

And she’d use that for, like, warming the water for a bath?

R – Yes. And boiling all her clothes up and all.

That's it, aye. So there'd be no water upstairs, just downstairs.

R- No, just downstairs.

And in the cellar, were there?

R- In the cellar, yes.

Now did your mother warm the water for the washing? Was that warmed in the gas boiler and all?

R- She used to warm it, what do you mean? For washing up?

For.. No, for washing clothes.

R- Oh for washing, she used to use that boiler, yes.

Yes. Did you have a stairs carpet?

R- No. Stair mats, she used to put little mats. Square mats were put up the stairs.

Were they wooden or stone?

R - They were stone.

Stone. Aye. Stone steps.

(300)

R= Yes.

Were the neighbours the same? You know?

R- Yes. The majority had them, they were the same, just odd uns would have some carpet you know. What were a bit better off than we were.

That's it. What kind of curtains did you have? Blinds, curtains, what did you have?

R - Well we had curtains up yes. But when the war were on we used to have black out blinds. The black uns what we used to put up you know?

That's it. Yes.

R - But we did have curtains, you know?

Yes, black out. Can you remember any families in the street not having curtains?

R- No.

No. Did they used to donkeystone the door steps in the street?

R - Oh yes, door steps and window bottoms yes.

Aye. How about the kerb edge?

R -- Yes.

Kerb edge and all? And round t' coal hole.

R – Just odd uns used to do the kerb edge, but not everybody.

Aye. There were nobody black leaded tram lines were there?

R- No. We used to blacklead the fireplace.

Aye, that's it aye.

R- We had a big fireplace with the big door on and me mother used to

blacklead that and all, aye.

That's it. Aye. Like she'd bake in there, wouldn't she? Aye.

R- She baked in the oven. Yes, we used to shove coal, fire under the oven aye.

That's it, under the oven. Did you have one of them porcelain enamel trays in the hearth that looked like tiles? Or was it a stone hearth?

R- It were a stone hearth. Yes.

Aye. If you remember they got round later to having them porcelain enamel things in the hearth didn't they, that looked like white tiles.

R- Yes, that's right, yes they did.

Was there a big fender?

R- Yes there was.

Aye. How was the house lit Jim?

R – Well, that was lit by electricity when we, like when we moved. But I think there were gas in there. I don't think we used to, their were gas in upstairs, come out of the walls in the bedrooms you know? But we didn't use gas.

Yes. So that were the first time your family had electric light, when they moved into Burnley Road.

R- Yes.

Before that, they were on gas. Aye. How did you get rid of the household rubbish?

(350)(15 min)

R- Oh we used to throw it, put it in the dustbin or burn a lot of it you know? Or take it to the tip. take it to the tip in a wheelbarrow, in a truck.

Was it a dust bin or was it an ash pit?

R - We had, we had a dust bin, but there were ash pits outside as well. you know?

Yes. Were they still using ash pits'?

R- Oh yes. Anyway you can burn a lot of stuff in your ash pits as well, you know. And they were across the road were us ash middens, we’d to walk across the road to tip them in you know. There were some out t'back but ours were across the road.

Yes. How often did they clean them out Jim?

R - Once a week.

Once a week? Ash middens and all?

R - Yes. And us toilets, some were across the road. You'd to go up two steps and to the toilet across t’road and all.

Yes, so some of them would have been dry toilets would they?

R- Yes they were.

Aye, were they still coming round to empty them? Buckets?

R- Used to come in, yes with, with a tin in the back, yes.

Aye and powder? Sprinkle powder in aye. How often did your mother do the washing?

R- Well she used to wash a lot did me mother, when we were young you know. A few times a week but she really had a good wash on Saturday, a really good washing day were Saturday, you know.

Saturday. Aye, now that's, that's an uncommon day really for washing in't it? You know it used to be Monday. How long did it take her to, when she did a big wash how long did it take her?

R- Oh a couple of hours with all the washing she had to do. Yes, it took her a fair bit.

How did she dry it?

R- Well either hang them outside, or on the old clothes line in the front room you know.

Clothes rack that you pulled up on pulleys?

R- Clothes rack what you pulled up on pulleys, yes,

Yes. How did she iron? What sort of iron did she have?

R- She had one of them gas irons, what you, you lit inside.

Aye that's it, aye with a gas pipe to it, aye.

R- With a gas pipe aye. Yes.

What can you remember most clearly about washing day?

R- I don't know, all the clothes hanging from off the clothes lines and having to bob down and walk up and down with ‘em all dripping and what have you. That's most as I can remember like.

Had she a big mangle?

R - Oh yes, one of them. She’d take us two lads to move it.

Who twined that?

R- Well, me dad used to do a lot of that for her, yes, mangle for her. It were right heavy were that mangle, it were right biggun. And we used to get two hands on to it, it took me all me time to move it round, it were a big thing. Aye.

Yes. How did your mother clean the house? When she set to, to clean the house up, how did she do it exactly! You know, what did she use to do it?

R- What, in what way do you mean?

Well I mean, nowadays there's all these spray things that you put on furniture and God knows what but in those days there weren’t so ...

R- Oh aye. Oh yes well she probably did like they do today. She'd ...well, we had coconut matting down you see, that were very dusty and she started, she used to have to clean that first, then the dust settled and then she'd start, she’d then go round with the duster you see then. And then polish.

Yes. How did she clean the matting.

R- Well, she used to brush it. But sometimes she used to take it outside and beat it, you know how it were. Oh terrible dusty.

Yes. That's it. Aye.

R- And then, when she'd took it outside I used to help and sweep up for her you know, sweep all the dust and what have you because it left a lot of dust did coconut matting. {Because of the open weave and the hard texture.]

Did you do a fair number of jobs round the house?

R- I did a lot of jobs round the house, I used to help me mother a lot. Mop and all, and do all sorts aye.

Yes. Was there anything when she was cleaning up, that she used to take particular care of? You know, that she used to really think something about?

R- Well. She used to do her own ornaments and that, she wouldn't let us go and do all the glassware and things like that. She used to do them all herself then, so as you wouldn’t break them you know? Them were the special things for her.

What were them, like wedding presents and family heirlooms and what not?

R- Yes, and brass things.

Did the older children help the younger ones? You know, with dressing and eating, or anything like that or did your mother used to look after the children?

R- My mother used to look after the children,.

Did your father do any work round the house?

(450)(20 min)

R- Not a right lot, no.

If he did anything round the house what would he be likely to do?

R- Well he did like all the odd jobs you know, like what wanted doing. Like do it yourself things in the house you know, what wanted mending, anything. But he wouldn’t do housework, like mopping up and things like that. But he, anything what broke or anything, he’d mend it you know and things like that.

Aye. That house in Burnley Road, did the family own it?

R- No.

So they rented it did they?

R- Oh it were rented yes.

Have you any idea how much rent they paid?

R- I think it were five shilling a week.

Who were the landlord?

R- Do you know I don't know who the landlord were in that house.

Did you ever hear your parents talking about the landlord? Whether he were a good landlord or a bad one or what?

R- I think the landlord what owned them houses, I think she lived at Blackpool. I think she were called Miss Bailey and she lived at Blackpool but they never did a right lot to their houses. She were a poor landlady. Yes.

Yes. Did you ever see her?

R- No.

Who collected the rent?

R- They had a rent collector what collected the rent but we never see Miss Bailey who owned them no.

Did your mother ever do any work in the house to earn a bit of extra money you know, like washing or sewing?

R- She used to baby-sit a lot. Look after children for other people what went to work.

Aye, she child minded. That’s it.

R- She did a lot of that. Yes, she did a lot of that.

How much did she charge 'em, can you remember?

R- Do you know I don't know, about ten shilling or five shillings, I don’t know exactly. Somewhere about that. She used to have, sometimes she used to have two in the house, you know that she looked after.

Yes. And she'd look after them children while the mother were at work. That’s it.

R- All day yes.

And did anybody else in the neighbourhood do anything like that?

R- I think they nearly all looked after children round that area you know.

Aye, the women who were at home?

R- Yes. But a lot went to work you know.

Is that house in Burnley Road still standing?

R- No, it's been pulled down now.

Aye that’s been pulled down and the other one that…

R - That what?

The cellar house, is it still up.

R - Yes, Broad Ing’s still up yes. But that what we lived in, what I were telling you about, now there was a Club, Working Men’s Club in Middle Row and it's still there now.

(500)

And they’ve, there's a house at either side to keep it safe like and they're building a new club round there, over the back in the meadow at the back.

Aye, that's where them right big stones are in the wall, in the chimney breast.

R - Yes, well that’s what we are talking about now, we are members.

Which house was yours? Right from t'club?

R- Eleven … twelve it was. It were the third from the club.

This way?

R- Going towards Burnley.

Oh, the other side then. So like it’d be the second one from the end that’s been knocked down now. Aye.

R- One, two, three, yes, second from the club.

Now then, your mother cooking. She cooked on the range? You’ve already told me haven’t you.

R- Yes, gas aye.

Can you remember .. what, she had a gas stove did she? Yes. When did she first have a gas stove, can you remember?

R- Eh, I don't know.

Aye. Do you know if she had one at the other house?

R- No I can't remember that at all. I know she had one all the time as I know when we lived in the other one at Loveclough.

Yes that's all right Jim. Did she make her own bread?

R- Yes she did, yes she used to…

Aye. How much did she make at one time?

R - I don’t know, about happen a dozen loaves I think. I'm not right sure, sommat like that. She used to bake once a week you know.

Aye so she'd bake a stone of flour then, wouldn't she? [14lbs]

R – Yes. Well, it'd last all week you know.

Aye. Did she bake cakes?

R- Yes I think she did, she did make ...

What sort?

R - I don't know, I’ve no idea what sort of cakes they were. Just ordinary cakes you know, and …

It's right, it's right. Did she make jam?

R- Oh yes, them round things what had jam on top, she used to make them.

Oh aye, them. Did she make jam or marmalade, did she boil ...

R- Oh no. She never made jam or marmalade, no.

Pickles? Home-made wine, beer? Did she make any of her own medicines?

R- No not as I know off.

What did you usually have for breakfast?

R - Jam butties. Yes, we used to have jam butties a lot.

And how about Sunday dinner?

R- Potato pie. She used to make her own potato pies and what they call pea pies. She made them with peas and a crust on. Meat and potato pies.

(550)(25 min)

What would you usually have for your dinners during the week?

R- Oh, she used to buy meat and that at odd times you know. It'd be sometimes a bit of chicken and things like that.

Aye. Did you have any supper before you went to bed?

R- Just some biscuits. That's all. But jam and bread. We were brought up on jam butties. Yes.

Aye. Well, here you are. Did the family have a garden or an allotment?

R- No they didn't have anything didn't them houses.

Did they have any land anywhere about where they could keep a few hens or anything like that?

R- There were that land at the back what they're building the club on now. That were, what do you call it, you could build on there you know, you could put a coit on. There were coits on, hen coits ... [cotes] And people had hens in and a bit of an allotment, but there were some allotments farther down the road what people had.

But you didn't have one.

R- But we didn't have one of them, no we didn't have any allotments.

No. Did you have pudding every day?

R - No. No we didn't.

How much milk do you think the family'd have each day?

R- About four or five pints a day, we used to drink a lot of milk.

Was it delivered once or twice?

R- Twice I think. I think once at morning and after dinner.

Aye. Farm milk were it? Kitted?

R- Yes, it were farm milk.

Yes. What would you use it for mostly?

R- Well, me mother used to make rice puddings a lot with the milk and then we used to drink it and all you know?

Aye. How about butter, did you use butter?

R- Margarine.

Yes. How about dripping?

R- Yes, we used to eat a lot of dripping, get it from the butcher’s.

Aye. That's it.

R- For dripping butties.

How about fruit, what fruit did you eat most often?

R- Well we used to have, we used to eat apples and bananas and things like that. Apples, bananas and oranges.

What vegetables?

R – Cabbage and lettuce.

I’ll just shout some foods out here, different foods out here, and you tell me how often you had them, you know, or if you didn't have them at all. Bananas, you've already mentioned them. Yes. How often about?

R- Oh two or three times a week, bananas.

Rabbit.

R- Once.

Fried food, you know fried stuff?

R- Yes, I know what you mean. Perhaps twice a week.

Fish?

R - Once.

What sort of fish did you have?

R- Fillets it were, not plaice.

Aye. When did you usually have that?

R- I think she got that at Friday I think. I'm not right sure.

Aye, Friday were a fish day, weren't it?

R - Yes I think it were Friday when she got it.

Cheese?

R- Once or twice, cheese, yes twice a week cheese.

Cowheels?

R- Well she used to get cowheel happen once a week but I never eat cowheel, I didn't like it.

Tripe?

R- Oh tripe yes, about three or four times a week tripe, we had tripe.

Trotters?

R- No, I never had trotters, I didn't like them.

Black pudding?

R- No.

Eggs?

R- Oh yes. I used to eat plenty of eggs, nearly every day I eat eggs.

Where did they come from?

R- From the farm. From the farm at the bottom in the, down at the bottom of…

Yes. Tomatoes?

R- About twice a week tomatoes I should think?

How about grapefruit?

R- No, I weren't a lover of grapefruit, none of us liked grapefruits.

Were they about? Can you remember seeing them about?

R- Do you know I can’t. I don’t know whether they were about or not. I can’t remember grapefruit. Of all the fruits, like oranges and things like that and grapefruits no.

Aye, it’s funny that. How about sheep’s head?

R- Oh no.

You laugh when I say that. Why? Generally what they buy for the dog isn’t it. There are a lot of people lived on sheep’s head weren’t there. Can you remember having much tinned stuff?

R- A lot of tinned stuff, there were a lot in them days of tinned stuff. There weren't a right lot of fresh things in them days, nearly all in tins you know.

What kind of tinned stuff, anything?

R- Well, what they have today, a lot. Like tins of fruit and what have you there were. And tins of like soup weren’t there, we used to have tins of soup.

Can you ever remember having a bad tin of fruit or food, do you know?

R- Well I can't. No, I don’t know that me mother mentioned it at all.

How about tea? Did you drink a lot of tea?

R- Yes, mostly tea.

Cocoa?

R- We had cocoa. I didn’t care much for cocoa. We used to have it, I used to have Ovaltine. Yes.

(30 min)(650)

Ovaltine, yes. How about coffee?

R- No, I'm I’m not a lover of coffee, although I drink a lot, or quite a bit of it now, but didn’t then.

What did you have for Christmas dinner?

R- I think it were like chicken. I don’t know if we ever had turkey, happen once you know, just an odd time.

What was your favourite food when you were a child, can you remember?

R- Oh I had a steak and kidney pudding.

Is that right?

R- Made in a rag. Eh it were good were that, she used to make a lot of that, it were lovely. That were my favourite, were that. Gorgeous it were.

What did you have to eat if, you know, if it had been a bad week and the family were a bit hard up?

R- What did we have to eat? What, a bit of jam, or a bit of dripping. Jam and dripping on bread.

Did your dad come home for all his meals?

R - Yes he did, dinner and tea. Because he only lived, he only worked at the bottom, you see, at the bottom of the brew, yes. [Brew = dialect for brow or steep road]

Did he always have the same food as the rest of the family or did he sometimes have something different?

R- He had the same as we all had.

Can you ever remember your mother going short of food to feed the rest of you?

R - Oh yes, many a time.

Many a time?

R- Never had a meal sometimes. Just leave her meal for us to eat, to give it to us. Oh yes, a few times..

When things were a bit rough?

R- They were rough, and they were rougher when the war started and all you know when everything were rationed. When rations came in.

Yes. We’ll get on to that Jim. You see that's the reason for these questions. To build a picture up, you know you start to get a picture. Who usually did the shopping?

R- Well, me mother did, or sometimes I used to go up to the shop you know, because the shop were only at the end of the row.

Aye.

R- What they called Noel's shop what's pulled down now.

Noel's?

R- It were called Noel Sutcliffe’s shop. Noel Sutcliffe he were called and it was just at the end of the row you see and we did our shopping there.

Yes. Was all the shopping done there just about?

R- Yes.

Aye. Did she ever go down to Rawtenstall to the market or owt like that?

R- No, not as…

Were trams running on that road then?

R- Do you know I can't remember trams. There were trams, there were tram lines were on, but I don’t know that I can remember trams or not. I don’t know whether they give up running or not when I were a little un. But the tram lines were there but I think there were buses when I can remember, but they've only just given over running.

So you'd never shop at the Co-op?

(700)

R- No.

Did the shop at the end of the row give credit?

R- Yes.

Did your mother have credit?

R - Yes. They had what they called a book you know.

That's it. I were going to ask you that Jim, yes, is that how they worked it, with a shop book?

R- Yes, he used to write it down in the book and then when me father fetched his wage home she used to go and pay.

Go and pay up.

R- Or sometimes if she couldn't afford it she’d to pay so much off it and leave some on for next week. A lot of them did that them days, you know, it were a regular thing. Yes.

Oh yes. A tremendous number Jim, it was very common. Can you ever remember anything about pawnshops, were there any pawnshops about?

R- Not up there at Loveclough, no they were in Rawtenstall were the pawnshops.

Were they patronised do you know, did people used to use them?

R- Oh yes, I believe so, yes.

Well, yes, you say you believe so. Like, have you ever seen anybody taking something there?

R- No, I haven't actually no.

What was the general attitude towards pawnshops? Were they regarded as a good thing or a bad thing.

R- I don't know, some people said they were all right you know. Where they can take stuff to get money for them but me mother didn't agree with them didn’t me mother and a lot didn’t.

(35 min)

If say your mother had seen somebody going down the road with father’s Sunday best suit and the best Sunday frock, to go and pawn them. What would her view have been? Would she have been a bit scathing about it, or would she have thought that it was a good thing that they could go and do that? You know, what would your mother’s attitude have been.

R- Oh, my mother, I don't think my mother would have thought a lot about it you know. She'd have probably thought she's a bit brazen going selling stuff like, you know?

Aye. Yes, a lot of pawnshops used to have a back door that you could go into instead of going in through the front, didn't they?

R - Yes, they probably did.

Is there anything that you can remember eating when you were young that it's no longer possible to get. Can you think of anything?

R - Eh no, I can’t.

How much housekeeping do you think your mother’d have then, any idea?

R- I don't know. About eight pounds or nine? Something like that but I don't know for sure. There weren't a right lot of it you know.

How much do you think your dad was earning?

R- I don't know. I haven't a clue. I never knew what me dad were earning.

No. Now then, the second world war, of courses there were rationing.

(750)

R- Oh yes, rationing books yes.

Now then. Were food short?

R- Yes. It were short.

Can you remember queuing?

R- Yes with ration books, yes I did. I remember queuing.

How about the black market. Did you ever get anything you know, like, from the farm?

R- Me dad used to get different things you know, a bit of butter, a bit of sugar. But like we never knew how he’d got it but he used to bring it home.

That's it, aye. Good lad, good job somebody did.

R- Yes, he looked after us all like that.

[At this distance in time it might surprise readers that I seem to like the idea of the black market. Speaking as one who benefited from it, we had a fairly pragmatic view towards it. Extra rations were very welcome and we knew that people who could afford to eat in restaurants had no problem about supplementing their diet. It seemed to that what was sauce for the goose was sauce for the gander and in a way we were getting one over Hitler and the system.]

Yes. Would you say you were better fed or worse fed during the war than you were before?

R- No, I think we were about the same you know. I don’t think we were really worse off, even though there were rationing. We seemed to get through all right you know, we weren’t short of anything, you know.

Which were the things you missed most with the rationing?

R- I think it were like going to the butcher's and buying meat and that. You were just restricted to so much meat you see at the butchers.

Yes. How were the rabbit job?

R- Happen an odd time a rabbit but .. all the best meat and that, it were out you know.

Yes. Right, clothes Jim. Did your mother make any of the family's clothes?

R- No. She never made any at all.

Did she have a sewing machine?

R- Oh yes. She used to do a lot of sewing like but she never made any clothes.

Did she mend your clothes?

R- Oh yes.

Darn socks?

R- Darn socks and put patches on our pants.

Did she use a mushroom or her fist?

R- Her fist, yes.

Did you ever have any passed on clothes?

R- Yes, a lot of them. We got off all the different people you know. Shoes that were a bit too big for us and things like that.

If you had any clothes bought, where were they bought from?

(40 min)

R- They were bought from a salesman what came round, like a club.

Aye. What were that? Provident?

R- That were… They were a firm from Burnley. Reynard’s they were called, at Burnley, Reynard’s. She used to pay them so much a week for clothes off them..

She’d pay so much a week, yes. What did they call that fellow, had they a name for him?

R- What came round?

Yes.

R- Well you know. I never knew his name. Well I did but I forget you know, I can’t remember.

No. But some people used to talk about, like the Scotchman coming round you know. Provident man or Tally man.

(800)

R- I can’t remember but I can picture him now you know, coming. And we all used to say that Reynard’s is coming you know. And he used to come in then. But we were nearly always out playing, very rare we stopped in, you know?

What happened to your old clothes?

R- I think me mother used to give them away to other people you know, what needed them.

What did you wear for school?

R- Short pants and stockings, boots, or clogs actually. And a little coat, well a little blazer, and a little cap.

Aye. Was there a clogger at Loveclough?

R- Yes there were a clogger in the row.

What was his name?

R- Foster he were called, yes. And he used to make all his own clogs, and then he’d iron us clogs.

What did your father wear for work?

R- He used to have a boiler suit, and he had boots what he had when he were in the Home Guard. He were in the Home Guard and he had boots what he went to work in.

Home Guard boots.

R - Home Guard boots, yes.

Good man. What did your mother wear when she went shopping?

R- Just an ordinary pair of shoes, low flat heeled shoes.

How about clothes? What sort of clothes did she wear?

R- Well, them right long ones, down to her ankles, like flowered, like a skirt. Sometimes she had a frock, a shawl, she used to have a shawl.

Yes, but fairly long skirts.

R- Yes, right down to her ankles yes.

Aye? There’d be plenty going about with them shorter than that then, wouldn't there?

R- Yes. But she did have them shorter ones later on but I remember her having the long ones.

That's interesting aye. Did your dad ever mend your clogs?

R- He used to iron them yes. He used to go and buy irons from the cloggers and he used to iron, clog 'em himself.

How many outfits of clothes did you have at any one time?

R- We just had the clothes what we wore through the week to school, what we used to go to school in and then we had some old ones what we changed into at night when we came home to go and play out and then we had a best for Sunday. Always had a suit for Sunday. We used to always have to keep that [special]

How often did you have clean clothes?

R- Do you mean a change of underclothes?

How often changing clothes yes, that's it.

R- Oh we used to change ‘em every week like. But we didn't wear underpants or anything like that in them days.

That's it yes. When you were first…

R- No vest. No, we had no vest, no underpants.

Were your trousers lined?

(850)

They weren't lined.

R- No.

When's the first time you can remember wearing underpants Jim?

R- When I started work when I were 14. Yes when I started work at first, that's when we started wearing them and a vest, but up then we never wore them.

Good. And your mother was in a savings club, she was in Reynard’s.

R- Yes. She were in Reynard’s aye.

What sort of change did you see in the sort of clothes that were being worn during the war? Like, were clothes that people were wearing, the ones after the second world war as they were before, or did you see any change in the sort of clothes that people wore?

R- Oh there were a change yes. Like same as you said about women with their frocks a bit shorter. I don't know, I think that fellers pants, all the pants and that were all turn-ups. But I don’t know about suits, whether they changed or not, we hadn’t a suit.

How about colours?

R- No, I can’t say I took much notice of them really.

Yes. That’s all right Jim. We’ll end this tape here and put another on, we’re nearly off.

SCG/07 July 2003

7,384 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 79/SD/02

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON AUGUST 14TH 1979 AT 26 HARGREAVES DRIVE, RAWTENSTALL. THE INFORMANT IS JIM RILEY, MULE SPINNER AT SPRING VALE MILL. THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Did everyone sit down for their meals together?

R- Odd times yes, I mean, like we used to have ours when we came home from school.

Aye, and your dad’s would be later?

R- And me dad used to work while half past five, and we used to come home at about quarter to four, four o'clock and we used to have our tea and go out [playing]. And me dad come home at half past five, and then he'd sit down to tea with me mother then you see.

(50)

Did, when you were all sat down together, like say Saturdays or Sundays or holidays, anything like that, did your parents have any rules about how you behaved at the table? Were they strict with you at all?

R- No, not right strict but we, you know, we hadn't to act the goat or anything. We hadn't to do a lot of laughing, we had to get on with us meal and that were it you know.

What were they strict about, you know like times for coming in or swearing or being cheeky or owt like that?

R- Oh they weren't right bothered about times for meals. Like we used to come in when we had been playing out, but we never swore in the house, never. Even today, in front of me own father I never swear at him. No, never have done. We'd one rule we never did, we never swore.

Yes. If you did do something that were wrong how did you get punished?

R- Me dad used to get his belt and he used to belt us with his belt.

Aye. Did that happen often?

R- Yes quite a bit. And it…

When you say quite a bit, you know, how often?

R- Well, I don't mean every day, but twice or three times a week. If we weren't behaving ourselves he used to take his belt off and he’d hit us with the buckle.

With the buckle end?

R- With the buckle end, it were really, it were bad.

Looking back, what do you think about it now? Do you think he was a bit hard an you?

R- Well, no personally I don’t. It were a bit harsh at the time when we were younger but do you know it were a good thing really. It learnt us you know. We suffered a bit like with the buckle end but I think it did us good you know?

Were you the same with your son?

R - No, different altogether with our Ian, our Ian and Sheila.

Yes. Now why? If it were good for you why is it not good for them?

R- I don’t know. It’s a different upbringing today to what it were in them days.

Aye. But you never felt any animosity towards your father because of the fact that he was strict with you?

R – No. I didn’t bear any grudge at all you know.

That's interesting Jim. No grudge?

R – No. None at all.

That's interesting when you think about it and yet you wouldn’t bring your children up that way.

(5 min)

R - No. I've said to ours many a time, “My dad used to hit me with the buckle end of his belt when we did anything wrong and all as what I’m doing to you two is shout at you.” You know or else raise me hand you know. But never hit them you know. But we used to got the belt, oh yes. It hurt aye.

(150)

Lass and all?

R – Oh yes.

What did your mother think about that?

R- Oh she were, she didn't like it you know but he were the boss were me dad, he were the boss in the house. What he said went.

No messing about?

R- No.

A bit more about that later Jim. I think that's interesting. Did anybody ever say grace before meals?

R – No.

Ever have any prayers at home?

R – No.

Going to bed?

R - When we were younger we did yes.

If you had a birthday was it different from any other day? Did you ever get birthday presents?

R- No.

How did you spend Christmas, New Year, you know?

R- Oh we had a good time at Christmas. We used to get, me dad used to do… well, he’d put a big pillow at the bottom of the bed. We’d get apples, oranges and some games, and we had a good time at Christmas.

All right. How about Easter? Was Easter a big holiday?

R- No, not really, we had all Easter holiday at schools, you know but we weren't anything exceptional.

Did you ever have pace eggs, anything like that at Easter?

R- No.

Were there any musical instruments in the house?

(200)

R- We had a piano accordion but nobody could play it.

Aye. How come you had a piano accordion?

R - Do you know I don't know. We found it one day, me and our Jack, when we were rooting upstairs in the long drawers and we pulled it out and at the bottom the piano accordion were in. And we used to be playing it you know, in and out with it and making all sorts of noises but nobody could play it. I don't know how it come to be there.

Aye. That's interesting..

R- And I never knew whose it were.

Did any of you sing?

R- Me dad used to sing. A good singer were me dad.

Where did he sing?

R- He used to sing in the clubs, he used to sing in t'club on the row you know. He were a good singer when he were younger.

Did he sing at home?

R- Yes he did. He used to sing a lot knocking about in the house but he didn't actually sing a song to us.

Yes. What were the name of that club?

R- Loveclough Working Mans Club it was called.

I thought it were, aye. C.I.U?

R- yes, it was a C.I.U. club. [Club and Institutes Union Affiliated.]

Were there any games you played in the house? You know, say it were a bad day.

R- Yes, we used to play a lot of games, snakes and ladders, draughts and things like that.

Did your parents ever play with you?

R- Yes. Well, I’ll tell you what we used to play a lot of, table tennis. We had a little snooker table. We were mad on snooker. Me dad were a good snooker player and he taught us how to play snooker. He had a little table and we used to put it on the big table after tea. Aye, we used to play snooker and billiards.

Was there anybody in the family that couldn't read or write?

(250)

R- No.

Did you have a regular newspaper?

R- Yes.

What was it?

R- Do you know, I don't know what it were called. I don't know what. The Express, were it going then?

Yes it were going.

R- Yes I think it were the Daily Express.

How about magazines, woman's magazines?

R- Me mother had a woman's magazine yes.

Which one, can you remember?

R - Do you know I don't know whether it were the Woman’s Own or not.

Aye. How about, you know, Children’s Newspaper, anything like that or comics?

R- We used to have comics, used to have the Beano and Dandy, and Film Fun and Knock Out. Yes, all of them.

As you got older did you get on to the Wizard and Hotspur?

R- We went on to books then yes and Hotspur and things like that yes.

Aye. They were good weren't they?

R- Ye. Our Ian has a load upstairs of them now. Victors, nearly brand new, he had them since he were a little un and they’re in good condition.

Eh I can remember I used to look forward to the Wizard and…

R – Yes, they were good.

Hotspur.

R - Hotspur, there were Film Fun. Eh…

Do you remember Wilson?

R- Yes.

The man who knew no fear.

R- Yes.

And Rockfist Rogan weren't it?

R- yes. They were good were them.

Eh, Those were the days Jim. I’d better shut up, we are sounding like a couple of old men. Library, was anybody a member of the library?

R – No. Me dad used to do a fair bit of reading, but it were books what he got at work, you know, he borrowed off…

Were there any books in the house?

R – Yea, what me dad had, that's all.

(10 min)(300)

What sort of books would he read?

R- I think he liked detective books did me dad. And we had a Bible, we had a Bible in the house.

Family Bible.

R- Yes.

Were it one of the big uns?

R – No. It were only a little one, a small one.

Who read that?

R- Well we all use to read a bit of it you know at odd times like when we were younger like. And we used to go to read it before we went to school, at Sunday School you know.

Yes, well I’ll be asking you about that. What time did the children go to bed?

R- When we were younger we used to go about six o'clock, half past six.

Aye, winter and summer?

R- Yes. Well, winter six o'clock, summer happen about seven or half past seven, but no later.

How about your mother and father, what time would they go to bed?

R- I think they used to be in bed by about ten o'clock. But me dad used to be in later than that, he went to, he used to go to the Club a lot you know?

Yes. How often did he go to the club?

R- Oh pretty regular.

Every night?

R- No, not every night but nearly every night, just odd nights he stopped in but nearly all t’fellows were club goers then, you know.

Did you have any pets?

R- I didn't but me brother had, be kept rabbits, he had a few rabbits, and we had a budgie, we always had a budgie.

Budgie. Oh aye.

R- Yes. Me dad always had a budgie in the house, we used to have two.

Did your father smoke?

R- Yes.

What, pipe?

R- No, cigarettes.

Did your mother smoke?

R- Yes.

(350)

Fags?

R – Yes.

How about your brothers and sisters?

R- No. None of us smoked.

Aye. You don't smoke now either, do you?

R- I used to do, but I gave over.

Aye. When did you start?

R- When I went into the Army and I were 19.

Did anyone in the family ever have a bet?

R- No. Oh, me dad used to have a bet.

Horses?

R- Yes and football.

And football? That’d be pools?

R- Yes, he did the pools, but he didn't do the big pools, it were local, a local coupon you know?

When can you remember seeing your first radio?

R- Eh! That's one of them half moon shaped things, you know.

Well, you know, wireless, radio, anything like that you know? Did you always have one from when you can remember?

R- I can always remember us having a radio yes. We were never without a radio.

Aye. Were it mains or battery, can you remember?

R- Mains were this one, mains.

Now then, if you were outside the house, where would you usually play?

R- All over, we used to play in the main road a lot because there were very little traffic and we used to put t’coats down in the middle of the road. [for goalposts]

Burnley Road?

R- On the road itself and play football.

It’s hardly credible now is it.

R- Yes. And the playing ground were only 50 yard down the road but we never played on it, we used to play in the middle of the road.

Eh God.

R- But on Sundays we used to go down on the park, there used to be a lot of us then you see playing cricket and football.

Who did you play with?

R- All the lads what were local, me brother and…

Was there anybody that you weren't allowed to play with?

R - No we could, we’d play with anybody.

What games did you play?

R- Cricket, football, that were it.

That were it, nothing else? How about rounders?

R- Well we’d play rounders with the girls, and what they called Tin In the Ring. We used to play that. But football and cricket, nothing else, we were that were mad on them, that were the game for us.

Aye, what sort of a ball?

R- Tennis ball.

For both?

R- For both. And sometimes we used to play with somebody else’s case ball, what were a bit better off than we were. And when it got busted, we used to play with the bladder inside and then if the bladder busted we used to stuff the casing with paper and we used to play with that then.

Aye, that's it. Did you ever go for walks?

R- Yes we did a lot of walking.

Did you ever have a bicycle?

R- Yes. Nearly always had a bike, I were mad on bikes. I were keen on tinkering with them you know. I used to mess about with ‘em and anything wrong with a bike, they used to bring it to me and I used to mend it for them.

Did you do a lot of cycling?

R- I did quite a bit yes and me dad used to do a lot you know.

Oh, did he have a bike and all?

R - He had a bike yes. Dad had a bike, and me and Jack had a bike, yes.

Did you use to go off together?

R- Yes, set off when it were nice in summertime.

I'll ask you some more about that in a minute or two. Did you ever go out collecting, you know, Whinberries or Blackberries or firewood?

R- Just odd times. Firewood yes. Aye for the fire yes many a time. Early on, early on in the mornings.

Aye. Where did you go?

R- Up in t’woods. Sometimes we'd chopped little trees down and then we’d to saw it up into little logs and then chop it up. We used to do that regular for to save the coal, put a bit of wood on with a bit of coal.

(450)

Did anyone in the family ever do any fishing?

R- No.

Did your father go out in his spare time apart from the club?

He were a mad on bowls. He played a lot of bowls. He won a lot of things with bowls, canteens of cutlery and little cups, oh yes.

Aye, he'd have his own woods?

R- He had his own woods yes, still has them today.

Still bowls does he?

Only odd times, not so much now.

That would he Crown Green, wouldn't it?

R – Yes.

And you say he had a bike and all. And where would he go if you and him set off, where would he go?

R- Oh, we used to go round Whalley, Clitheroe, all round there.

Yes. When would that be like, Sunday or a Saturday, or what?

R- That were at Sundays.

What did your mother do in her spare time? That’s if she had any?

R- Go camping, she did a lot of camping. Gossiping, you know, going to…

Neighbours ..yes.

R- Neighbours yes.

Was there anything like, you know, Women's Institute, well not Women's Institute, Mother’s Union…

R- They had a Women’s Institute then but she never joined in with them, but people used to come to me mother, camping and they would to go to the back door of the pub with a jug, fill the jug up with beer, take it back home and have a drink and a natter, you see when nobody were in.

(500)

That's it yes. I shall ask you about that in a bit because that’s interesting. I’ll stick to the order the questions are in so we don’t miss anything. Did your mother and father ever go out together?

R - No, me dad always were out on his own.

Can you ever remember him taking your mother out?

R – No. No I can't, me mother were always at home.

Can you ever remember your mother setting off anywhere by herself and going somewhere, you know, that you'd call, sort of exceptional, like going, getting a train and going…

R – No. I don't think so, no. The farthest she went were just up the road to me dad’s sister’s, that were me auntie Bertha.

(20 min)

Where were that at?

R- That was just where you pass the petrol station coming over the moor at Oak Mill at Dunnockshaw. When you're coming through Dunnockshaw there's a petrol station on your left.

Yes.

R- Well just past there there's some houses on your right hand-side and me auntie used to live there, that were me dad's sister.

Yes, just beside Clow Bridge Drive, yes.

R - Well that’s as far as she went, that were it.

Yes. Did the family go to church regular?

R- No. We used to do when we were younger, me and our Jack and our Marion, we used to go to church.

And Sunday School?

R- Sunday School yes. We used to have to go to Sunday School on Sunday. Yes.

Did you go to church as well as Sunday school?

R- We went to church as well yes because it were a Church of England school you see?

Aye, that’s it. What, church in the morning and Sunday school in the afternoon?

R – Yes.

And how about church at night, did you go again at night?

R - We didn't go at night no.

No. So your mother and father didn’t go but they made sure you went.

R- We went, we always had to go to church yes.

Did your mother ever go to church?

R – Not as far as I can remember. No.

Were there any social events connected with the church that you went to? You know, can you remember anything like trips, anything like that?

R – No, we never went on any.

Did you over go away for a holiday when you were young?

R- Not to stay, just odd days to Blackpool.

You can never remember going away for a week’s holiday?

(550)

R – No, never had a week’s holiday, not when we were younger.

And if you had a day out would there be anywhere else apart from Blackpool where you’d go?

R - No it was just Blackpool.

Always Blackpool.

R - On the sands.

Train?

R- Yes.

There, from Rawtenstall?

R - Yes.

How did you get to Rawtenstall?

R- By bus.

Bus?

R- Yes there were buses round, you know?

Would you all go together if you went for a day at Blackpool?

R- Yes all together.

Did your dad go as well?

R- Yes, all the family went yes.

How often can you remember doing that? Roughly? You know, was it fairly regular or was it…

R- No it weren’t regular. Just the odd time.

Aye. Were there any other sorts of outings or visits, when you were young, apart from cycling with your dad.

R - No. No it were all more or less playing round home, you know?

Were any of the family ever connected with the Temperance Movement?

R- No.

Did anybody ever tell you anything about the evils of drink?

R – No.

Did you ever sign the pledge?

R- No.

Can you ever remember seeing women going into pubs when you were young?

R- No that weren't done weren't that. That’s why they used to always go to the back door of the pub.

That’s what I said I’d be getting round to. If a woman went into a pub on her own, like she couldn't go in the club on her own could she, she wouldn’t be allowed in.

R- She weren't allowed in the Workingman’s Club, no.

But was there a pub in Loveclough as well?

R- Yes, it were the Glory.

Glory, that's it yes, of course there is.

R - You pass it coming here.

What would be the attitude to a woman that went into the bar at the Glory on her own?

R- Oh I don’t know, they'd probably talk, do you know. I don’t know really whether, what they used to think about them like that. It just weren’t the done thing you know in them days.

It was certainly frowned on wasn’t it?

R- yes.

Do you know of any families that wore ruined with drinking? Do you know any families where any of the parents drank far too much?

(600)

R- There were me uncle Joe, he used to drink a lot.

Were that your father's brother or your mother's brother?

R- No, me mother’s brother, and he really did drink excessively you know. He were always drunk. Nearly every night when he went out he used to drink a lot.

Was it a fairly common then Jim to see drunken people about?

R- Yes. Drunken fellows, yes, we used to see them, well rolling out of the pubs and all out of the clubs and they'd stagger out at the front door and right into the main road as soon as they come out of the front door you know. Yes, there were a lot of drunkards in them days. They used to drink a lot did fellows.

Tell me, is it my imagination? I don't seem to see as many drunken people about now as I used to. What do you think?

(25 min)

R- No, I don't think you do. Yes I see quite a few knocking about but I don't think…, I don't know. I've seen a lot of these young lads what’s drunk today, whether they are drunk or whether they put it on or not I don't know but there were a lot of them when I were younger used to be drunk during the day did a lot of fellows you know?

In the local pub and the club were certain rooms kept for certain people, or did anybody booze anywhere?

R- No. There used to be a tap room for the blokes and no women were allowed in it. It were just for the men for to play darts and dominoes and swear you see.

Yes that's it. Tha’rt right. Eh aye, I can remember when I was in a tap room one day and a woman come in. It was like, God, I don't know what it was like, somebody swearing in church. Aye. Can you remember seeing any street performers or people selling stuff who entertained passers by?

(650)

R – No. Not round our way no. No I never seen anything.

No. Can you ever remember people coming round the streets, knife grinders?

R- Oh yes, a rag and bone chap coming. And sharpening your knives and scissors, there used to be a bloke on a pedal bike and he used to lift it up and pull the stand out, and then sit on it and pedal away and sharpen your knives and scissors, oh yes, we used to see them pretty regular.

Aye. There were one in Barlick you know, and I always laugh when I think about knife grinders, they used to call him Flagger, because he couldn't afford a bike and he used to come and knock on the door, get your knives and scissors, take them to grind them and he used to go round the corner and sharpen then on the kerb stone. He’d make a good job, but sharpen then on the kerb stone. We used to call him Flagger but he always did it round the corner, he didn't do it in front of your house.

R- Yes, that's right, yes.

Can you ever remember your dad sharpening the carving knife on the door step?

R- Oh yes, big knife yes. On the door step.

Did you have a stone slopstone?

R- Yes.

Did he ever sharpen it on the front of that?

R- Sometimes he did, yes.

Aye. That’s why a lot of them are worn down at the front you know.

R- Yes, it used to have worn kerb, that’s it.

That's it, that's why a lot of them are worn down at the front with sharpening the carving knife on it. Did you belong to any clubs or societies? You know, before you left school, you know like church choir or Band of Hope or the Scouts or Guides or owt like that?

R- No.

No. Of course you wouldn't be in the Guides would you!

R- No I wouldn't.

They are awful anyway, they wouldn't let you in Jim.

R- I shouldn't think so.

What did you think of Loveclough as a place to live in when you were young? Looking back now you know, what do you think of Loveclough as a place to live in?

R- I thought it were all right, I thought it were a nice place. It were a grand place. There were, like better than living in town because there were, you’d more freedom there were plenty of areas for to play in and for to go walks and play in. You’d to make a lot of your own entertainment in those days because there was nothing for you to go to. But like same as me, the open spaces and the fresh air, and I thought it were all right, I thought it were grand you know.

Yes. Can you ever remember going to a wedding when you were young?

(700)

R- No.

Or a funeral?

R- No. No I can't. We stopped at home I think when there were funerals. My mother and father used to go but we didn’t.

Where did you enjoy going most when you were a child? You know, if somebody had come to you and said “Right, you can go anywhere you want today Jim.” Where would you have gone?

R- To the pictures. I used to like to go to the pictures.

Did you used to go a lot?

R- Once a week.

Yes. Did you have any pocket money?

R- Yes, sixpence a week.

Well, you weren't doing too bad then!

R- No, but with that we used to .. a penny bus fare, well, twopence, a penny down and a penny back, twopence in the pictures and twopence to spend, that were sixpence.

That were the pictures.

R- That were it, aye.

What were the pictures you used to see, can you remember?

R- Hopalong Cassidy and Buck Rogers. Oh yes.

Yes. Flash Gordon?

R- Flash Gordon yes. I used to sit in the twopennies, the first four rows at the front.

(30 min)

That’s it, aye.

R - And get a crick in your neck watching it!

That's it, aye. Flash Gordon, eh, how about that?

R- I used to like that aye. It was grand.

Aye. You and me were going to the pictures at about the same time, I’ll tell you.

R- Eh I used to enjoy it.

I'm just trying to think what t’other were that used to be on. Aye there were the Lone Ranger weren’t there and Hopalong Cassidy

R- Yes, and there were someone else….

And there was one feller, I know I always used to think he was a bit of a bloody puff and I can’t think. It wore a serial, it used to be on each week.

R- Yes it were.

And he were a big soft looking bugger. I can’t remember Jim, I can't this minute…

R- No I can't remember. There is a few and you can’t remember.

Now you've said that your mother's friends used to come camping. Did your father’s friends call at the house often?

R- Yes. They used to come a few times did me dad’s friends.

What would they come for? Just for him to go out or…

R- Just for camping and then a lot of them used to come to have their hair cut, he used to cut hair. And he also mended watches, he were a good watch mender, very good at watch mending.

Aye?

R- Yes he used to mend anybody’s watch, pocket watch, wristlet watch. If you had one, but mostly they were pocket watches, you know, with chains. But he were… And he were also keen on photography, he used to develop his own. He had all the equipment for developing, trays and such. Aye he were pretty keen on that, he had a few hobbies had me dad you know, he were very good at it. And he still cuts his own hair today, he cuts his own hair, with the mirror, big mirror in the back and…

Yes. Aye, it's funny that, I used to work with a fellow that used to do that, aye. [George Bleasdale, engineer at Bancroft.]

A Bancroft picture really but Frank Bleasdale, George's brother who was winding master at Bancroft used to cut hair free in working hours.

R- With the scissors. And he’d never been to a barbers had me dad in his life.

Would friends call in at the house you know, just call in as they were passing or would they sort of need to be invited?

R- No, they used to, if they were walking past the house and they'd just knock on the window. All right Bill? And then they’d come in and have a natter.

Yes. How would you spend Saturday when you were young?

R- Get up in the morning, go playing football, and then look forward to going to the pictures this afternoon. That were like a ritual more or less. Saturday afternoon pictures.

How about Saturday evening?

R- Oh Saturday evening, football and cricket again. And in summertime if we’d been to a cricket match at Saturday afternoon, which we used to go to then, we’d get the wickets and bat out at night, and play cricket and that until we got shouted of to come in.

Did you ever go to any concerts or theatres or music halls or owt like that?

R- No.

Just the pictures.

R- Not when we were young, later on in life we used to go to…

Later on. Yes well, there you are, what I’m talking about now really is before you left school.

R- No we didn't go to any, then.

And then, you know I’ll ask you [in] a bit about school but ... I'll have a quick glance at a bit of politics now. Can you remember anybody in the family ever discussing politics?

R- Never, no.

Do you know what views your father held?

R- Well, he were Labour were me dad, he always had been Labour. They never discussed politics, but I know he were a Labour man.

Yes. You've no idea why he was a socialist, do you know?

(800)

R- No I haven’t, I have no idea no.

How about your mother?

R- Well, I don’t know, not to my knowledge she hadn’t and she never used to discuss it.

Can you ever remember her voting?

R- No. I can’t.

Can you remember your dad voting?

R- I think he did use to vote yes, but I don’t know, not really. I think he did vote you know but I can’t remember.

Was either your mother or your father a member of a political party, you know, were they actually members?

R- No.

Can you remember anything about elections when you were younger? You know, were they big things elections or were they…

R- I can’t remember, no.

No. Have you ever heard your father say anything about women? About women having the vote or women’s role in life? Anything like that?

R- No.

What would you say was your father’s views about women? You know when you think of it, this isn’t meant in the spirit of criticism, it's a way that a lot of men used to think in those days and it sounds to me as if your father was one of them. I mean him and your mother never went out together, and your father would think that doing housework was, you know, it was below him really to do housework wasn't it? I mean like mending something that was broke were a different thing altogether. Now these are all fairly common views. Would you say that your father had a, you know, in some ways really quite a low opinion of your mother. Can you understand what I mean?

R- Yes I can understand what you mean .. but I don't know ... He always said to us like “She is to stop at home and do the housework and look after the children” and that were it you know. That’s what she were there for more or less.

Ye, that’s it. A bit like the Andy Capp thing isn’t it, “A woman’s place in the home is in bed unless there’s coal needs fetching in.”

R- Yes. In the home .. that's reight yes. Well that were his view I think.

Aye. And what are your views on that Jim?

R- What, for today? Now?

Yes.

R- Well I don’t agree with that way at all. Probably because I used to help me mother a lot when I were younger. I think times were pretty hard for me mother. And I think he could have given her a bit more help, like same as she had to fetch coal and things like that.

That’s something I wanted to ask you, what sort of a life do you think your mother had.

R- I think she'd a damned hard life personally. It were hard work bringing us up. And me dad used to go out, have his tea and go out and leave me mother to it you see? And she had to sort everything out, and meals .. which women do today. I know some women what do today, they have it all to do some women today, their husbands go out but I don't agree with that. I think if you are married to a woman, I think you should be fifty fifty, you should pull both ways. And that's how, that's .. you know, that makes your marriage. Everybody hasn't the same view, you see but…

But yet, do you think that nowadays, under the sort of freedom that we have nowadays, I don't know, but I've often thought that if women were treated like they were say in the twenties and thirties, I think they'd just up and leave home. But in those days they never, they just never did it. Really, your father, well not just your father, but would you say that it was true that men in those days they really had, they'd got the clean end of the stick hadn’t they?

R- Oh yes. Everything were going right for 'em. They had the best end of the stick. And all as they did were work and fetch the wage home and go out and have a good time in the pub and come home and that were it you know, and have a good time, and t’mother were at home….

Now would you say that he had that attitude because .. would you say it was because he was naturally a hard rotten bugger, or would you say it was because that was the way he’d been brought up?

R- No. That were the way he'd been brought up. I don't think he were, as some would say, a rotten bugger. That were the done thing them days.

Yes, everybody was the same.

R- Everybody were alike, he didn’t do anything out of the ordinary. The other blokes what went in the club with him did exactly the same thing.

Yes. When you think about it, it’s interesting isn’t it because just about everybody you talk to says the same thing. I think that women must have had a terrible time you know, in those days Jim, honestly. It's one of the things that comes over to me time and time again and when you think of the number of women who were not only doing all the housework but out spinning or weaving all day and then going home and doing all the housework.

R- And then going home…. Aye.

And I mean, from what you've told me, your father wasn't a drunkard.

(900)(40 min))

R- No.

He’d like his drink, and he'd go and have his drink but I mean your mother could have been a lot worse off. She could have had a husband who was actually boozing all the money you know and…

R- Yes. But he looked after us at home, we were, you know, we didn’t go short at home.

Yes that’s it aye.

R- But some did used to go out boozing and take all the money with ‘em and just leave a little bit for the wife to sort out.

Did you know any families round about .. Now we are not talking about being ruined by drink and this that and the other, but did you know, were there people about who were worse off than you?

R- Oh yes. There used to be a family, called Fawcett and they lived up on the hill side in a little cottage, and they really were rough. Now stone floors and all as they lived off were jam and bread, and the lads used to go to school, same school as I went to, and they used to wear women’s high heel shoes, and women's frocks, they'd no pants. Like we had little shorts, little short pants. Nowt like that, no stockings. Really rough. And the mother left them when they were little and the father used to bring them up and he were out drinking all day. He would come home everyday drunk. And sometimes they used to sit outside the pub did the lads waiting for their father coming out of the pub and he’d be drunk when he come, and then they used to take him home. And every time you went in that house that table, they used to have like one of them old-fashioned tables with four legs, the old wooden topped things, and it were full of jam and breadcrumbs and stale bread and dripping and that's all they lived off. They really did rough it. Aye, terrible. That’s why I say we were a lot better off than a lot of people were. Some were better off than we were but I don't think we were poor by any means. But this Fawcett family were poor, and the lads have suffered since. Now they’ve got older they’ve got ulcerated stomachs, they’ve had a rough time as they’ve grown up. I know now, Arthur Fawcett, Billy Fawcett yes they’ve really had a hard time when they've grown up. They’re as old as I am you know and they’ve all had trouble with their stomachs. And that were all caused with their upbringing when they were little. They used to go, no raincoats or little coats to their backs, used to go out in the rain and rainy days like this, saturated, just dripping off their hair and off their nose. Terrible, shocking, I know nowt like it, you couldn't credit it, how, you know, people living like that. And they did.

(950)

Were there, would you say that there were those people that were better off than yourselves, how could you tell they were better off?

R- Well, they were better off. Like same as the clothes what they wore, they were a bit better clothes than what we used to wear.

What sort of jobs would their dads have?

R- Well I don’t know. I don't know what they did. They used to work at C.P.A. and all but I think their fathers were printers, like you know that were a good paid job were printers, and it is today at C.P.A. They’re on top money is the printers. And they had, the younger lads had a bit more pocket money than we had, you know, and their houses were a bit better than what ours were, there were a lot more carpets down in the rooms and …

There wouldn't he a big variation in the houses in Loveclough though would there?

R- No. They were nearly all the same type of house you know?

Yes, because Loveclough really, when you look at it, it's one of your actual factory villages. I mean, nearly all them houses would be put up at the time the mills were being built wouldn't they?

R- Yes, they were all round about the same.

It's not like, did Loveclough have a church?

R- They had a Providence Church. That were, that's up against the boundary there where you come on to the boundary. They didn't have an actual…

Yes but they didn't have an actual Church of England did they? Where did you go to church?

R- Yes, they had a Church of England but it were up on the top round what they call Swinshaw Lane. It were a big church, we used to go there from school, we used to walk it, used to come out of the school and up the path way and on to Swinshaw Lane and than we used to walk it to the church. And then we used to got to it off the main road which to down by the New Inn and we passed through the New Inn and we used to go up there and then into the church and it were just up Swinshaw Lane, that were a Church of England school were that.

When you say Providence what were that?

R- That were a Providence Methodist Church, my wife were, she used to go there. She were a Methodist my wife.

Aye. Methodist aye. Was she a Methodist? Aye.

R - Yes, and we were Church of England..

Oh I'll have to pull her leg about Ranters and Congos and such. That’s what they used to call than in Barlick. The Primitive Methodists were called Ranters.

R - Did they? Is that right?

Aye. Ranters and the Congregationalists were called the Congos.

R - I've never heard that like, I've never heard her mention anything like that.

Oh aye. Ranters and Congos. Reight, I’ll tell you what, that’ll do for tonight Jim.

(992)(45 min)

SCG/08 July 2003

7,175 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 79/SD/03

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON AUGUST 14TH 1979 AT 26 HARGREAVES DRIVE, RAWTENSTALL. THE INFORMANT IS JIM RILEY, MULE SPINNER AT SPRING VALE MILL. THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Right we’ll go on with education a bit now. We’ll just probe into your education a bit Jim.

R- Don't probe right deep.

Now then, what school did you go to?

R- Just a small primary school across the road. Just across the road from where we lived.

What were the name of it?

R - It were called Rows school.

Aye. Was it an endowed school or a board school or what was it. Do you know?

R- No. It just were an endowed school like well ...

With the church?

R- Yes, C of E school, what were run with the church.

Yes. Like did they have a board of governors, and the parson were on it, you know?

R – Yes. The parson were on it, he were on it, from the church.

And he'd come down once a week or so? Aye, that’s it.

R- Yes and they used to give … yes.

How old were you when you first went to school?

(50)

R- I think I went when I were four. I just was four when I went.