TAPE 82/HD/01

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 20th of JULY 1982 AT BANKS HILL, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS HAROLD DUXBURY AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Harold Duxbury in 1982.

[Harold Duxbury was a building contractor, owner of Briggs and Duxbury in Barnoldswick. Apart from his general knowledge of the town and how it functioned Harold was closely associated with many of the mills and in particular the Calf Hall Shed Company.]

R- I'm 82 this week, on Saturday.

And where were you born, Harold?

R - I was born in Wellhouse Square, Barnoldswick.

Ah, just by the mill there.

R - No, off Twenty Row. [Built as accommodation for workers at Bracewell's Wellhouse Mill, hence the name.]

Oh yes, I'm thinking of ... I'm sorry I always think, when somebody mentions Wellhouse Square, I don't know why but I always think of that square of houses. Yes, that's it, off Bank Street.

R - Yes, well it's the end of Bank Street, it's the end of Wellhouse Street.

That's right, it's me, I'm getting mixed up. Now, how many years did you live in the house you were born in?

R - Well, I was carried in the arms down to Carr’s House, Full Syke, down here on the right so I would probably be about six months old then, but I couldn't walk.

Carr House

So you only lived at Wellhouse Square for six months.

R - For six months, yes.

And then, you and your family moved down to Carr’s House?

R - Yes.

And how long did you live at Carr’s House?

R – ‘Til I was nearly 9.

Well, the questions I'm going to ask you about the house you can remember most about will obviously be Carr’s House. Do you know why your family made that move?

R - Well, this house became vacant and my grandfather lived at and farmed Crook Carr Farm. That's just across there and so my father was interested in his own neighbourhood and in that house. Therefore, I think there was about seven acres I would say to the house which my Uncle Oliver farmed. He took on the farm buildings and we, our family, lived in the house.

And where was your father born?

R- At Earby.

Do you know exactly where?

R- No.

Why did he come to Barlick then?

R - Well, my grandfather Duxbury was an overlooker in the mill at Earby and he fancied farming so they went, took a farm at Paythorne, Higher House Farm. They were there, not a very long time and then they moved to "England's Head" farm. (5 min)

Aye, now where's that?

R - That's at Paythorne and there's a footpath that goes through the farmyard and you can go on this footpath from Paythorne pub right through the farmyard at England's Head and come out at the stepping stones at Nappa across the stepping stones in the Ribble. You've seen them I presume. The family went to school at Paythorne and the school in those days was the old Toll Bar which still stands at the top of the hill leading down to Paythorne Bridge and that used to be the day school.

The Toll bar at Paythorne road end near Demesne on the Long Preston road out of Gisburn.

When you say 'the family' that’d be your father’s.

R- My father's family, yes. All the sons and daughters. You see, to give you a short history of the family, from England’s Head Farm they came to Crook Carr Farm which is just here which is quite a good farm. I should give you a few more details about Paythorne I think. I know it's going back. You see there was very few shoes and that kind of thing in those days. They were all clogs. They used to have to walk from England's Head to Barnoldswick to get their clogs wrung [ironed]. They went to, as it were, Greenwood Hartley on Jepp Hill. They had a little shop there. I don't think you'll remember it but I do. I remember Greenwood Hartley being there and he was a clogger. They used to bring their clogs there to be re-wrung. I suppose one of the lads would bring the lot but they'd to walk it, it was the only way. In those days my grandfather was a Methodist local preacher and I believe he was quite a good preacher.

What was your grandfather's name?

R - John.

John Duxbury.

R- And my grandmother's name was Brown. You know Willie Brown of Henry Brown Sons and Pickles? His father and my grandmother were brother and sister. Willie Brown and my father were full cousins. (50)

Now, your grandfather went out to Paythorne from Earby then, so he'd met his wife in Earby.

R - Yes.

Aye, that's it, yes because the Browns, they were in Earby too.

R - That's it. Now then, going back again, I don't think I need to say much more about Paythorne. My mother's side, if you want to know anything about my mother's side. My mother was called Gill. She'd several brothers and sisters all in Barnoldswick.

What was her Christian name?

R- Sarah. My grandmother Duxbury’s name was Sarah too. (10 min)

But anyhow, they came from Greenhow Hill which is near Pately Bridge. There was a big family of them and my grandfather used to own the lead mines at Greenhow Hill. He was bondsman for somebody, was my grandfather and they let him down and he paid up, paid every penny and came to Barnoldswick with nothing.

Have you any idea of when that would be roughly?

R - As near as I can tell you, Jubilee Year, 1887.

So he came from Greenhow down to Barnoldswick in 1887. He’d be .... When you say “your grandfather”, you mean your grandfather Gill.

[I have come across several references to Moses Gill being coachman for William Bracewell at Newfield Edge. Now Harold made two statements that bear on this; he said that his mother Sarah was ten years old when she came to Barlick and started work in New Mill as a throstle doffer but he also said that the family came to Barlick in 1887. We know that the family was in Greenhow Hill in 1881 because of the census record. Sarah was ten in 1882 and William Bracewell (Billycock) died on the 13th March 1885. Harold also said that he had an idea that Moses got the job at Newfield Edge because of the Methodist connection, he was a local preacher and Billycock was a strong Methodist. So, on balance, I think that Harold was wrong with his date and it was actually 1882 or shortly thereafter.]

R - My grandfather Gill

So he came down here and brought his family here. Presumably looking for work?

R - There was work here to be got, you see. The sons were experienced miners. So there was only one of the family, my eldest uncle, John, he went to a little place called Brotton which is near Saltburn, Redcar. There were iron ore mines at Skinningrove and he worked in the mines there and got married there and married a lady from Staithes and they had a big family. Gills all over the place, thirteen sons and one daughter and the daughter died and the other sons, well there's an abundance of Gills in that district. He was a big man, six foot odd and as straight as a rush when he was an old man. He used to come over and we used to look forward to Uncle John coming over and of course, we still keep in touch with the family. Occasionally we've gone over there and they've been over here.

So your mother was born in Earby?

R - No. My mother was born at Greenhow Hill.

She was born at Greenhow Hill, that's it I was thinking of Brown. That was your..

R- My grandmother.

Well, she was born at Greenhow Hill and she came down here and presumably she'd meet your father in Barnoldswick.

R - That's right. My grandfather went working at Newfield Edge. Slaters. [Joe Slater rented the house after Bracewell died and in fact married one of his daughters.]

Now do you mean the house at the bottom of Folly or do you mean far Newfield Edge up at the top?

R - I mean the house at the bottom of Folly.

Newfield Edge in about 1910. The farm buildings were behind and to the right.

That Slater built? [Mitchell built it in 1772 actually]

R - That's right. And he went working there and he worked there for forty years and never had a day off.

So what was his job there, Harold?

R- Everything.

Everything?

R - Yes, general factotum, bit of farming, milk hawking. He used to have a kit and he carried the kit on his back strapped on and they hooked it off. (100)

I've always thought of Newfield Edge as simply a mill owner's house but I take it there was some farm land with it as well.

R - Oh yes! There was farm land. There's farm buildings with it today. (11 min)

Yes, there is a cottage at the back and some buildings. Yes, that's interesting. When Slater came to Barlick and took that, well he came to Barlick and Slater had a mill at Galgate at Lancaster and he bought Mitchell's mill.

R - Wait a minute, you're talking about Billycock.

No, no, Slater - was it William Slater the first one. I've forgotten whether it was William Slater or John Slater but anyway he had the mill at Galgate and he bought Clough Mill [Mitchell’s Mill] in 1867 for £3,000 and that, as far as I know is when he came to the town. That's the first record I have of him coming into the town. whether he was a Barlicker before that, I don't know. He was certainly running the mill at Galgate because I got that from the Craven Bank records.

R - Yes, but I'm not sure on the ground here, that Fred Harry Slater who lived at Carr Beck, he owned Clough Mill. Now then, Joe Slater who owned, who was partial owner shall we say, with Fred Harry Slater, owned Clough Mill together. So they could be brothers but I'm not just sure. He lived at Carr Beck here and Joe Slater lived at Newfield Edge.

I wonder if William was their father, William Slater?

R - I don't know.

That's something that'll come out as I'm looking at other things. Your grandfather was working at Newfield Edge.

R - Yes. You see, I'm just inclined to think, I don't know, that there might be something just a bit with this William. You see it was William Bracewell, Old Billycock and he built the Methodist Chapel and he was, he lived at...

He lived at Newfield Edge?

R - He lived at Newfield Edge and he was the father of the Bracewell who was the vicar at Barnoldswick. He finished up his career here and his daughter... Old Billycock's daughter, Bracewell, married Joe Slater. They lived at Newfield Edge and so did Billycock before so Slater stepped in to Newfield Edge. Slater wouldn’t build it, Billycock might have built it. Bracewell's daughter was Mrs Joe Slater. (20 min) Now, she lived to be a big age and lived up there on her own and she had one daughter, Hilda Mary. Joe Slater was the father, Hilda Mary Slater. Mrs Slater, the old lady, Billycock's daughter, she used to get on to the telephone to my mother. It'd be two or three times a week and it'd be at least an hour. That was the only way that she could contact people and that was her means of communication with the outside world. Of course with my grandfather working there so long, she'd known my mother literally speaking all her life. My mother, when they came to Barnoldswick worked as a throstle spinner at New Mill. (150) Wellhouse Mill these days. Well it was Wellhouse Mill then I suppose but anyway, I suppose she… They all grew up, the daughters and sons and got married and raised their families. Peter Gill here is the grandson of my Uncle David and he was the next to the oldest of the Gills. John was the eldest then David and Peter is the grandson of David. There was Norman Gill, Val Gill and Morris Gill, Fred Gill and all these. They're in various parts of the country. Peter's probably the only grandson that is here in Barlick. Peter has the family Bible because I gave it to him, well I got it for him. He'll be able to help you a bit probably. Anyhow, I think I've said enough about the Gills.

Can I get a date down, how old was your mother when she died?

R - 86.

What year did she die, can you remember? What I'm trying to nail down is what year she was born.

R - Oh, I can get to know that for you. It's all recorded in the family Bible.

Oh, very good! Can you tell me, just for our conversation now, can you tell me roughly when did she die?

R - She died in 59 or 60.[1958 actually. Harold remembers it later]

(25 min)

So if it was 60 that would mean that she was born in 1833 or 4, something like that.

R - Yes.

1873 or 4, rather.

R - Something like that yes. Resulting in she wouldn't be working when she came to Barlick. I should think she'd be just about ready for working when she came to Barlick.

That’d make her about ten or eleven years old when she came to Barlick and that’d be about working age then. Good that's nice to nail that down, Harold. How many brothers and sisters did you have?

R - I had three brothers, that's four boys and three sisters.

There were seven children in the family?

R - That's right, yes.

Were there any children born that didn't survive?

R - Cecil who was next youngest to me died just before he was five years old. Not that he wasn't a strong, healthy lad, he was but you know, living down here. I mean our playground was the fields and the beck and quite a common thing was for us to go beck-jumping and falling in. They said it was croup and ulcerated throat but the doctors told us these days it would be diphtheria. Anyway, he died and he was a tartar! Held have been 80 just gone, March, just gone this 24th March.

So you'd be jumping over the becks down here and that would be just shortly after 1900.

R - That's right, I was born in 1900.

Can you remember when you were young and you were living at Carr’s House, were there any relations ever lived in the house with you?

R - No. (200)

You lived there on your own. Did your family ever have any lodgers?

No.

Your father's job. What was your father's job when you were born?

R - He was a joiner.

Did he become a joiner when he came back to the town? You know, when he was farming down here or was he a joiner and a farmer at the same time?

R - No, he didn't do any farming, did my father. He served his time at Earby with Dodgson’s. [Alfred Dodgson, ironmonger of 4 Victoria Road and Blacksmith of Lane Ends {Barrett 1902}] He was a joiner cum wheelwright cum, everything. That's where he served his time and then he came working for Proctor Barrett. He left there and went to Waite and Lamberts in York Street. He walked from here up there. I don't think he would be a long time at Proctor Barrett’s. Both him and Jack Briggs worked at Waite and Lamberts. From there [Carr House] we went to Bracewell School which is now the institute opposite the church. The teacher was a Mrs Watson and she lived in the top house at Park Road. On the long row, the little small houses. They called her husband Walter Watson. (30 min) And she walked from there down to Bracewell. She could walk! She couldn't half leg it! She did it for years and there was one class from bottom to top.

What ages would that be?

R - From five to thirteen.

How many were there at that school, roughly, any idea?

R - Somewhere between thirty and forty.

She looked after the lot?

R- She looked after the lot.

Can you ever remember when you were at school were there any school meals?

R- Oh no!

Was anybody ever given a free meal?

R- No.

We'll come back to that later because that's one of the interesting things. I'm jumping the gun now but we'll come on to that later. Your father, did he have any other job before he died?

R - Well, he was always in the building trade. They were joiners and builders and undertakers.

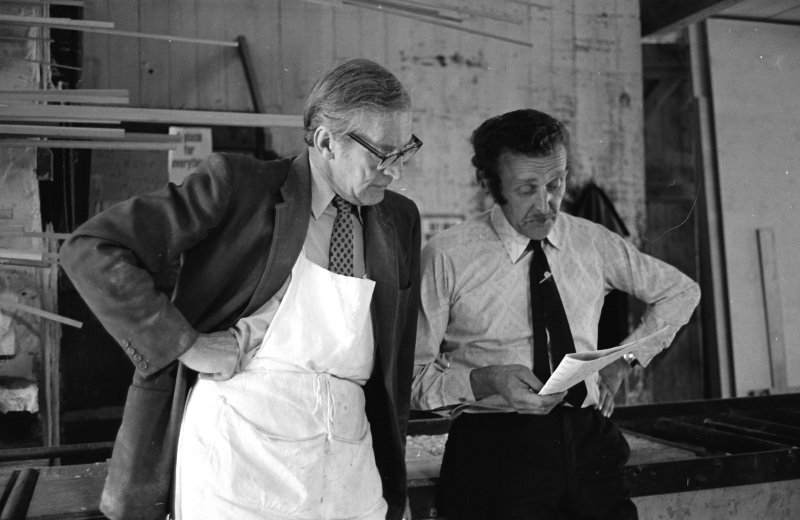

That's something that we've got to make clear, we've come to that now is that Jack Briggs and your father founded the firm of Briggs and Duxbury’s. Can you tell me about that?

R - Yes. it was on the Croft. Do you remember it being on there?

No.

R - Do you remember Jack Martin being on there?

Yes.

R - On the right hand side?

Yes.

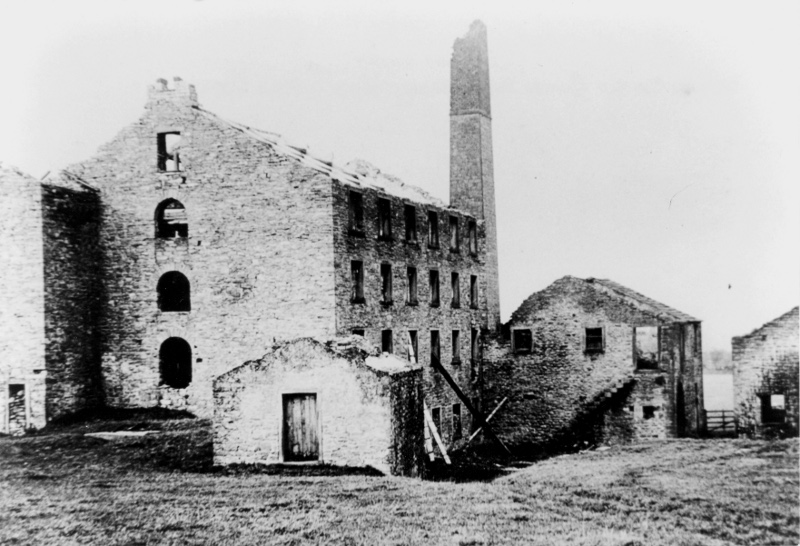

R - Well a bit further along on the left. This place that’s just been burned down a couple of years ago. That were our joiner's shop. The business was taken over, Briggs and Duxbury's took on the business of William Holdsworth or Will Holdsworth. He retired and they took on the business in 1909, March because I was only eight. And of course then we moved into the house right opposite the joiners shop that Will Holdsworth had. There was a little furniture shop as well with the house, you see and we kept that on and the undertaking, he did undertaking as well, you see. (250) And of course, he started with the undertaking right then, you see, right in the very beginning. And in those days, there was literally speaking, no mechanised machinery. The only thing that we had in those days was a circular saw that was geared and you had to wind the handle at the side like a wringing machine. We as kids, we had to wind this handle for them to cut the wood. As to how long they had that, I just don't know. Then we got a gas engine and we had it down below.

The empty site on the end where the wooden hut is was where Briggs and Duxbury originally operated from.

And this was on the Croft?

R - Yes.

Can you remember what year that would be about?

R - Well I should say about 1911 that we got a gas engine. Of course it was water cooled and all that kind of thing, you know. We used to have to heat it up and there was a kind of - not a Bunsen burner - but a long tool. You had to light it and that were the first job in a morning.

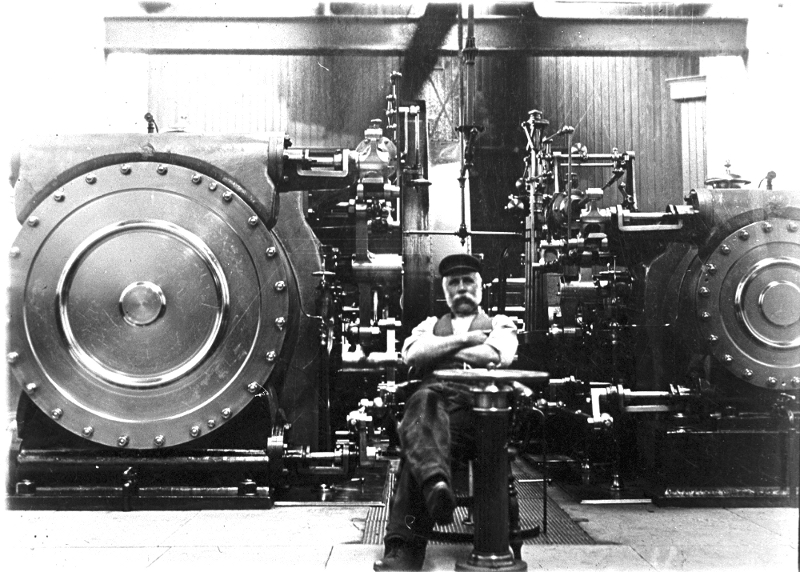

Can you remember what sort of engine it was?

R - I think it was a Crossley. (35 min)

A similar Crossley gas engine. This was at Empress Sawmills at Kelbrook.

Then we got a planing machine and a mortice machine and then we got a spindle moulder. Literally speaking, that's all we had for donkey's years.

When did the firm move from the Croft to down where they are now?

R- Down where they are now? 1936.

So they were on the Croft for a long time!

R - Oh yes, yes.

The name of that road, down by the side of Butts Mill there?

R - Well, it's just Butts.

Aye, Butts. I suppose that's why I can't remember the name of it. So your father would still be alive when you moved from there?

R - Oh yes.

Did he build that works purposely there? Did he build that works?

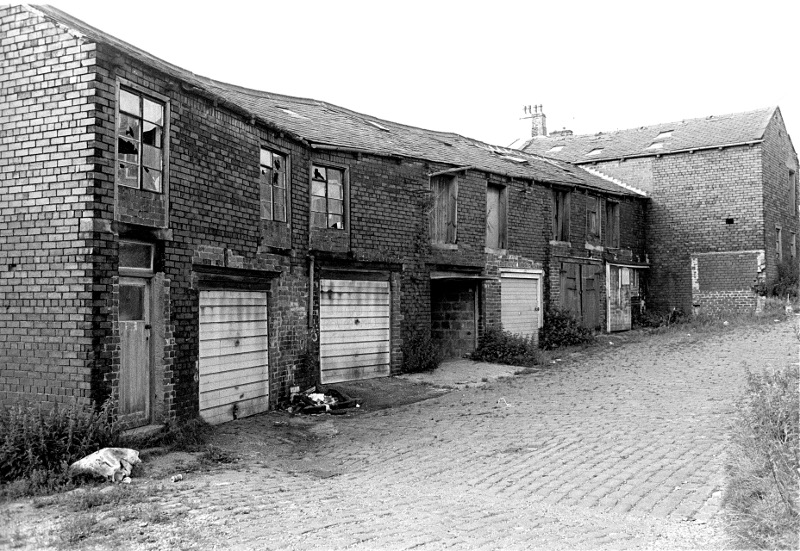

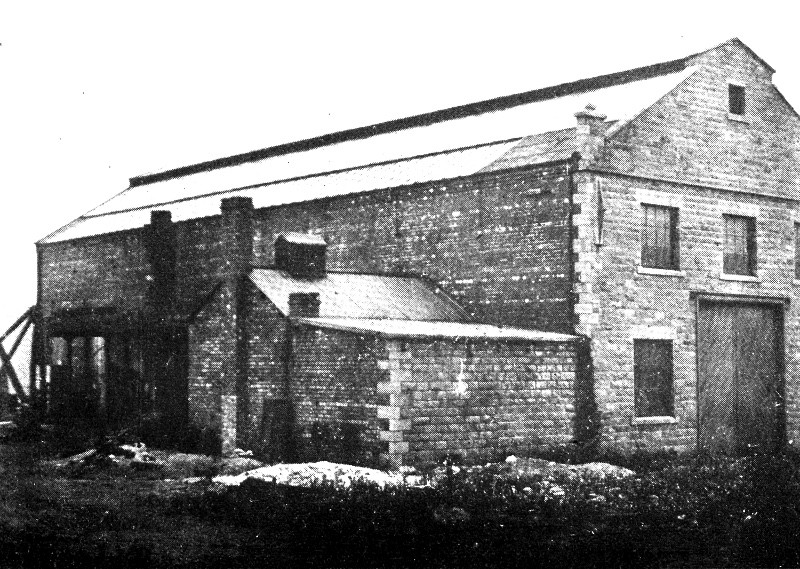

R- What, where we are now? No, it was a lodging house, model lodging house. There was two lodging houses, one that's a garage now, just at the bottom of Butts, you know and then there was this, and Bill Taylor built it.

The Model Lodging house in butts in about 1920.

This is the other lodging house which is now the Model Garage.

Built the lodging house?

R - Yes, where we are.

Now, can you tell me about the lodging house and about Bill Taylor? (300)

R – He’d been brought up in the building trade and he had a brother, Harry Taylor. They both built but Harry Taylor went to London but they built quite a few houses. They built Hollins Road. They built most of them up Taylor Street did Bill Taylor. He has a son living and two daughters living. Do you know Jack Starkie?

Yes.

R- Well, Jack Starkie's wife is Bill Taylor's daughter. She lives in Hollins Road.

So he built both those lodging houses?

R - No, no.

He built the big one that you're in?

R - Yes, the one that we're in. I'm just trying to remember who built the other but that doesn't concern us so much does it?

No, no, that's all right. When would that lodging house be built about, any idea?

R - I should look at deeds to give you ...

I was just wondering if you had a rough idea.

R - I'm not sure but I think it were built before the war. Oh yes, I should think it would be about 1911.

Why were the model lodging houses built?

R- Well!, there was so much cotton industry in those days and there was always work for weavers. These fellows that were on the road could weave and that kind of thing. They used to come and lodge there, you see. They could keep themselves. There were a common stove and that kind of thing and they'd cook for themselves and they used to go and stand at six o'clock in the morning at the various mills and if there was anybody didn't turn up at say by five past six one of these 'tramp weavers' would get put on. They called them 'tramp weavers'.

It nearly seems that if that model lodging house was up for sale in 1936 when your father bought it that there might have been less call for a model lodging house than there had been earlier. Do you think the numbers of 'tramp weavers' were dropping off?

R - Oh definitely. Yes. There wasn't room for two.

There wasn't enough trade to keep two lodging houses going?

R - No. I would say that the peak of the cotton industry were over.

Would you say that it wasn't so much that there weren't the people, the 'tramp weavers' still looking for work, it was that there wasn't the work there for them in the town?

R - That's right and of course, by this time, Social Security and that kind of thing were entering the pattern of life. They were state aided and they weren't depending on just what they could earn.

That's very interesting that Harold. When did your father die?

R - Now then, my mother died in 1958.

Ah well, you were only a year out.

R- My father died in 1954.

Ah, four years before. He were 82 when he died?

R - That's right and my mother were 86. Now then, she was ten years old when she came to Barlick. Now, I said Jubilee Year didn't I?

Yes.

R - I'm wrong . Jubilee Year was 1887.

Was it 87 or 90?

R - No, so it's going to be so she were fifty..

1958 she died and she was 86 so that's fifty eight from eighty six. So that's 1872, she was born. She must have been born in 1872 so..

R - No, no, you're wrong.

Fifty eight from eighty two - from eighty six rather is twenty eight. So twenty eight from a hundred is seventy two.

R - Yes.

And if she was ten years old when she came to Barlick they must have come in 1882. [This fits in with his being at Newfield Edge before William Bracewell died in 1885.]

R - She was ten years old when she came to Barlick.

Yes, so if she was born in 1872 which she must have been, that made it 1882 when they come to Barlick.

R -Our Wilfred were born in 1898.

And who was Wilfred?

R- My elder brother.

Your eldest brother, he was born in?

R - 1898.

Yes, well she'd be 26 years old then. Your mother would be 26 years old.

R - Yes, that sounds somewhere about right doesn't it?

So it's working out. Dates always are difficult and the thing about dates is, it's nice if you get some that are exact but .... (45 min)

R - Well it's going to be 1882 when they came to Barlick isn't it?

Yes, which is going back a long way. No, that's near enough. That's it. Now we were just talking about the model lodging houses. So Jack Briggs would still be a partner then?

R- Oh yes, yes.

So they moved into the works down on butts in 1936?

R Yes.

How long did Jack remain a partner?

R - Until he died.

When was that?

R- I can get that. I can give you the exact dates of that at a later date.

The last thing I want to do is worry you about dates because...

R - Well, it's only a matter of looking up in the funeral ledgers.

That's all right.

R - I would say it would be about 1950, I don't know.

Your mother worked originally as a throstle doffer at New Mill.

R - A throstle spinner.

A throstle spinner, yes. How long did she work, do you know?

R - Oh I don't know. You see, she'd be ten and she'd probably be married about 1895. I'd say she must have worked into the teens of years. I know they used to work in their bare feet.

As far as you know, did she work outside of the home once she'd got married?

(400)

R - Well, I wouldn't think so, you see, because she might have worked a few months after, I don't know.

Did any of your brothers and sisters leave Barlick? The thing I'm interested in is if any of your brothers and sisters left Barnoldswick at any time to go somewhere else to look for work or anything like that.

R - Oh no, not looking for work but before that period was the war, the First World War. Wilfred, as it was quite a common thing for these young lads, big strapping lads to give a wrong age and join the forces.

Of course, he’d only be 16 in 1914.

R - He were brought back out of France when he were 15, were our Wilfred. He joined in 1914 and we were weaving in those days at Bradley’s. They went off at breakfast time with two or three of them but I tell you he were brought back out of France. He was in the Scottish Rifles then and he was brought home because of his age. He were brought out of France before he was 16.

They found out....

R - My father wrote. He didn't mind him being in the forces but he didn't like the idea of him being shot at because he was a young devil!

When you say he was working at Bradley’s, where were Bradley’s weaving then?

R - Bankfield where Rolls Royce is.

Bankfield, that's it, yes. Yes, because they started that shed in 1905 the first shed.

R - Yes

Can you remember about the First World War starting? (50 min)

R - I can remember vividly the First World War starting.

Tell me about that Harold.

R - Well you see, there was panic everywhere and in those days you used to get 20lb bags of flour. Big white bags and 20lb in them. The first thing we had to do was to go down to the corn mill and get as much flour as we could with the trucks, you see. They didn't bake 3lb of bread then, I suppose it would be 20lb, I don't know. There used to be these big enamel dishes, yellow ones. Anyhow, the first really vivid… I was fourteen when the war started. Was I fourteen? Yes, I said fifteen didn't I. He [Wilfred] was going to be sixteen. Anyway, I was fourteen and Wilfred was two years older than me and the first real shock we had in Barlick was when the Rohilla went down. I was working then as a weaver at Bradley’s and there were a lot of Bradley's weavers that was on that ship that was lost. Of course I wove there until I was seventeen and then I came out into the joiners shop. (450)

How did you get to know that the war had actually started?

R - By telephone and Post Office. Notices put up outside the Post Office. Telephone and messages outside the Town Hall. There were daily, well two or three times a day messages when the Rohilla went down and put up outside the Post Office. And there was few people in those days had the telephone. I don't think we had a telephone in those days as a firm.

How about newspapers then Harold?

R - Well they weren't up to today’s standards were they really? They were a penny maybe, I think they were a penny.

The main papers in Barnoldswick then wouldn't be the daily paper, it would be the Craven Herald, would it?

R - Oh no, I wouldn't say so. There was daily papers. The Northern Daily Telegraph and that kind of thing which was published in the evening. There was the Pioneer in those days. There was news, literally speaking, telegrams coming in the First World War literally every day of somebody who was killed. You've only to look at this book, to see the number of people that were being killed. The paper, Barnoldswick papers, Skipton papers and that kind of thing and there was always a whole list of photographs of these lads who had been killed. (55 min)

What would you say was the general mood in the town at the beginning of the First World War? Was it quiet? Did people think it was a good thing or - can you remember anything about the general mood of the people?

R - About the war?

Yes, the beginning of the war.

R - Well, the general impression was that it wouldn't last until Christmas. It started on August 4th and it could be over by Christmas. That was the general attitude and the people - well I suppose that idea came from the top. Of course as you know, it lasted until 1918.

It caused a lot of trouble and a lot of deaths. So Wilfred went to the war but they brought him back.

R - Eventually, he went out to France again and he was gassed and wounded and transferred to the Seaforth Highlanders which is kilts. He was on the Somme, the Battle of the Somme which we have photographs of - well we had. Several Barlickers were killed during Ypres and the Somme. There were just a mad slaughter and there was a lot of Barlickers killed. They all knew one another so naturally they sought one another out. I joined the Air Force when I was seventeen. (500) You could volunteer, if you wanted to get into something special when you were 17. So I'd come out into the shop, into the workshop and worked as an apprentice joiner and tried to join up in, I think it was June. Yes, it would be June. After I’d been in the joiners shop about six months, and of course you had to have trade tests. Well, like, all my spare time being spent in the joiners shop, when I went into the joiners shop I wasn't just green. Anyway, it was so that I passed a trade test.

For the R.A.F.

R - For the RAF, yes.

Was it the R.A.F. or was it the R.F.C?

R - The 'Flying Corps' and I was in when it was changed to the RAF. And of course, I did the training and all that kind of thing at Blandford and Wendover and then went to Ireland. I was in Ireland when the war ended, when the peace was signed, you see and I can remember that night in November we were on guard, well we all went berserk that night and had a big bonfire and there was a big potato field just over the fence. We raided the potato field and we had roasted potatoes that night. I got out of the Forces in early 1919, in February I think. Yes, in February so I did less than a year in the Forces. And they'd have never made me into a soldier, I wasn't interested. I was interested in the work I was doing but not as a soldier. You'd to do your physical training and gun drill and all that sort of thing but I got so far and I was out as soon as ever I could. (1 hour) I was ready for out!

What I'd like to do now is just ask you a few questions about that house that you moved into. I assume it was on the Croft, next to the works.

R - Yes, yes.

The shop on Commercial Street which was also the Duxbury house.

Now, you moved up there in about 1909. How many bedrooms did that house have?

R - Three.

And what other rooms were there?

R - Living room, kitchen and a cellar - a big cellar. No bathroom.

Can you remember any of the furniture?

R - What, that were in? Well, there’d be an extension table and there’d be a couple of rocking chairs and maybe six wood chairs.

When you say a 'living room' that’d be like a parlour?

R - There's no parlour.

Well, that's a room separate from the kitchen.

R - Yes.

So actually, you lived in the 'living room'.

R - Yes.

That was what it was, you didn't have a parlour, a front room and...

R - No, no, no. Furniture shop was the front room. (550)

That's it, so there were three rooms downstairs and one of them was the furniture shop and that was where, presumably, where you sold the furniture that your father made.

R - Well not exactly, no. Furniture, three piece suites, linoleum, carpets and that kind of thing more than anything else but not generally speaking. Occasionally there was furniture in that was made across the road.

So which room did you have your meals in?

R - The living room.

Where did your mother do the cooking?

R- Well, we had a gas oven. In the first place we had the old fashioned Yorkshire range.

A typical cast iron kitchen range.

And what was in the living room?

R - That was in the living room. Then eventually we got a gas oven and she did the baking. She had a table in the kitchen and it was not a big kitchen but there was room to have a table about three foot long and two foot wide. Most of the baking was done there. The pantry was on top of the cellar steps. There was stone steps down into the cellar.

So where did your mother do the washing?

R - In the cellar.

Had you a copper?

R - Yes, a gas boiler.

So the only source of hot water would be either the gas boiler or…

R - The side boiler.

The side boiler with the Yorkshire range.

R - We had a gas boiler in the cellar and we had a galvanized bath, a tin bath and we used to have the baths in the cellar.

How often did you have a bath?

R - Generally speaking, Friday night - the children.

You know, I'm sure that when they listen to these tapes in the future they're going to laugh at me because every time I ask that question I laugh because they'll think that everybody in the country had a bath Friday night. The sewage system of this country must have been overloaded every Friday night! Well anyway, I'm sorry about that. You didn't have a bathroom and if you wanted a wash where would that be?

R - In the kitchen.

What sort of a sink was it? (1hr min)

R - Brown earthenware.

Where was the lavatory?

R - Outside, up the ginnel.

What sort was it?

R - Pail. Soil. Dan Derbyshire who lived next door and us joined at one toilet.

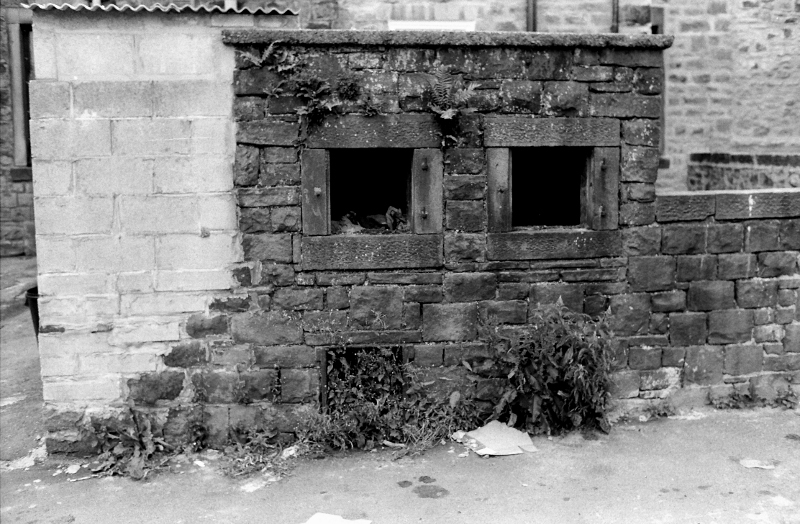

The small buildings in the gap in the houses on Roberts Street are the toilets Harold refers to. The Duxbury shop was at the bottom of the street on the left hand side.

And that was a pail toilet and who emptied that?

R - The Council.

Was it the Council that emptied it or was it somebody who contracted for them?

R - The Council.

And what was it emptied into?(600)

R - Into a soil cart, tank cart. You know, there was a horse and they emptied it in. They brought it down to the sewages in its present position on Greenberfield Lane and tipped it down there.

Old style night soil cart as described by Harold. You can see the door for emptying it on the back. Not the best job in the world!

How often was it emptied?

R - It must have been ten or fourteen days.

Did the house itself have piped water?

R - Yes, just cold.

How many taps and where?

R - There was one tap on the sink and one tap down the cellar.

What were the floors downstairs?

R - Down the cellar?

No, I’m sorry, Harold, I've phrased that question badly. The floors in the downstairs room in the living room and the kitchen.

H - The floors in the kitchen and living room were flagged.

Ah, flagged over the cellar:

R - No, the cellar was under the furniture shop. That floor was wood.

Did you have any carpets down in the living room?

R - No, not in those days. The only - a pegged rug, if you know what I mean?

Yes, I do Harold, but just for the people who listen to this tape and don't know what a pegged rug is, can you tell me what a pegged rug is?

R - A pegged rug was all hand made and we used to have to help to make them. Old clothes were cut up into strips. I would say probably 4” long and an 1” wide or ¾ wide we’ll say. There was what they called a 'pegging needle' and you pushed with an eye this piece of cloth in the needle. You pushed it through and up, you know, and up. (1hr 10 min) You got hold of the piece that you'd pushed through and got the needle out leaving it there, it hooked round, you see. Of course it was there for to stay, there was no question about that. We used to work patterns on them and all that kind of thing, designs and patterned diamonds, circles and so much in the middle one colour and then a border all the way round and that kind of thing and they were quite nice. (650) And then, after they had been pegged they were backed with Hessian which generally speaking was old bags, washed and sewn on the back and they were a nice job, a good job. Oh, I've helped to make hundreds of them.

Do you ever remember your mother putting sand on the floor?

R - No, I don't think so.

Have you got a stairs carpet?

R - Yes.

What kind of curtains did you have?

R - I would say that they would be printed cotton.

But would you say it was very unusual for people not to have curtains?

R - Yes. Generally speaking, people had curtains and with a roller blind. They didn't draw them to, they used to have these roller blinds - paper and with a pulley at the other end. A pin at one end and a pulley at the other and you wrapped the cord round a few times and then dropped the blind and it automatically wound round the pulley and then you pulled. it up, you see. They worked quite well.

How about the people in the houses nearby, how about donkey stone?

R - Wait a minute we're going back to the days when we lived on the Croft. We're not talking about when Mrs Bright came in 1940. Yes, you see the old donkey stone was quite a common thing.

No, there isn't much donkey stone about nowadays. How about the Yorkshire range? How was that cleaned?

R - Well there was only one way to clean it. It was what we used to call the 'ash hole' which was sunk and there was, in some cases a big ash pan, inside. Generally speaking ash hole, it was shovelled out of the ash-hole into a bucket and carried out into the ash-pit. Not a dustbin, an ash-pit. (1hr 15min) Of course you'd to clean out all underneath the oven and underneath the boiler. Clean all that out and this was done about once a week was cleaning the oven and all round the oven and all that kind of thing. Then, of course some of it was, not chrome plated but plated was the hinges and that kind of thing but the remainder was black-leaded. We used to have a brush purposely for black-leading, a little round one about an inch and a half diameter and you spit on the black lead and then shone it up with another brush, you see.

Who used to do that? Did your mother do it?

R - Yes.

How was the house lit?

R - Gas. We had a mantle, gas mantle downstairs but all the upstairs rooms were wall flames.

Fishtails?

R - That's right, yes.

So downstairs was the incandescent mantle.

R - Inverted.

It was inverted was it?

R - I think so, yes.

Was there any covering over it like a globe?

R- Oh yes, you see hanging from the ceiling. Well in those days it was a follow on from the oil lamps. Just an improvement from the oil.

Am I right, Harold, they used to call it a pendant fitting, didn't they?

R - Yes.

How about the gas mantle, say in Summer, if a moth got in or anything like that and started fluttering round it.

R - Oh well, they'd had it! They just dropped in bits, you see. You hadn't to touch them in any way or the mantle was ruined. If a bit comes off the mantle, the flame came right through and broke the glass that was somewhere near it and that kind of thing you see.

Can you remember when you first had electric light? The ashes went out into the ash pit. How did you get rid of the rest of the household rubbish?

R - it all went into the ash pit. (750) They'd come and empty this ash pit and there’d be half a dozen houses but there’d be special carts, low carts and they used to come and rake it all out and it used to be literally speaking half way across the street. Then a cart would come and shovel it onto the .. rake it all out - they had rakes. There was a door at the top to put it in and a door at the bottom to pull it out and they'd rakes to rake it out, you see. There'd be a cartload every time they came and that would be a weekly job.

Can I sort something out with you Harold that's bothered me for a long time. So if we're walking down a back street now in Barlick and you'll get some of the older back streets where you can see most of the cast iron doors have gone now but there used to be the cast iron doors on. You'll very often find three for one house and two of them, one is above the other. Now am I right in thinking that would be, if it's an old house, that would be where the midden was? Where the ash pit was? That you put the ashes in at the top and that it was raked out at the bottom?

Surviving ash pits in Barlick.

R - That's right, yes.

So in most cases, the ones that I've seen you'd have to go out into the back street to put the ashes in. (1hr 20min)

R- Yes, definitely.

And the other one, the other doorway, the one that's low down, that was the access for the pail toilet.

R - That's right, yes.

Of course, we're talking about the older houses.

R - Yes, well taking Commercial Street, a lot of the houses that was built say, after 1900, each had an ash pit for every separate house. You'd put the rubbish in, in the back yard and there’d be one outside to rake it out. In the one that I'm speaking of now on the Croft, it was a common one and there’d be six houses into that one and then Robert Street further on there, there was ash pits half way up and toilets. You see, in the middle of the street. The ash pits were outside and you went through a little ginnel into the toilets and there’d be four or five houses to the ash pits and four or five houses for two toilets.

So what we're now talking about is something that young people nowadays can't imagine. It's not something you'd like to go back to. There must have been smells and nuisances because of the fact that these toilets were pail toilets and there were these ash pits. Can you remember that? Is it something that's stuck in your mind? Was it something that you just accepted?

R - It was just accepted. You see when they emptied the pails into the cart, they used to scatter some kind of disinfectant in them, some dust of some description and that stunk as bad as the other! (100)

You just said something about dust.

R - A powder, I would say.

Yes, but, ordinary dust. Was there more dust about in those days than there is now?

R - Oh definitely!

How about flies?

R - Flies? Every house you went into had a fly catcher up! You understand what I mean by a fly catcher?

Sticky fly catcher.

R- Yes, some of them had two or three up. They'd be full of flies.

I can remember those when I was a lad before the war. These are things which I know about them because I’ve asked about them and you know about them but in fifty or a hundred years, people won’t believe it. You know, they'll have had no experience at all. So how did your mother actually do the washing?

R- Possing and wringer. Dolly tub and a wringing machine.

Did she have a scrubbing board?

R- Yes - a rubbing board.

Yes, a rubbing board, aye. Was the posser a copper one or a wooden one.

R - Copper one.

Dolly tub.

A copper posser. These were used in an up and down motion rather that a rotary movement like the old dolly posser and were thought to be more efficient.

How often did she do the washing?

R- Well, Monday was the washing day. (1 hr 25min)

Always? How long did it take her?

R - All morning - to wash. Then they had to be dried.

How did she dry it?

R - Well, out in the street across, the lines across the street and if it was bad weather, it was a clothes maiden in front of the fire.

Steaming away.

R - That's right, yes. Or a clothes rack, yes.

How did she iron it?

R - Well, in the early days, just a lump of iron heated in the fire.

Did it have a slipper?

R- No.

Did you just rub it?

R - Just rubbed it.

Some had slippers didn't they?

R - That's right, yes.

What would she go on to after that? Was it a gas iron?

R - it was a gas iron with a tube.

What can you remember most clearly about washing day? What sticks in your mind about washing day? Did the fact that your mother was doing the washing affect the meals you got that day?

R - No, it didn't. There’d usually be cold meat and you know, maybe carrots or turnips or cabbage or something of that sort, you see. Literally speaking the meat would be left over off the weekend joint. That was, generally speaking what mealtimes were. Ivy tells a story which is quite true. [Ivy was Harold’s wife] I’d better not say the places but as you know, I'm in Rotary and Ivy asked a certain Rotarian, “Well, did you have a good dinner today?" This fellow said, I can have a better dinner at washing day at home.." We always had enough to eat, we never went short of anything to eat. I wouldn't say it was the most expensive but you don't want me to go into diets and that kind of thing.

Actually, I will ask you particular questions about that a bit later because obviously that's another interesting area where things have changed a lot. People don't realise nowadays. Did you and your brothers and sisters have any jobs to do around the house?

R - Certainly, but Wilfred and I were both milk boys. In those days it was night and morning. I started taking milk from down here and I was only five years old.

Carr’s House?

R - Carr’s House. We continued taking milk. (1 hr 30 min)

I’m sorry Harold, did you say when you were five years old?

R - When I was five years old I went with the milk.

What time was that in the morning?

R - It would be seven o'clock. From leaving down here at seven o'clock. We went on taking milk right until I was full time at thirteen. I went half time at twelve and took (900) 1hr 30min. milk on the other half of the day. There did a law come in, and I took milk for my uncle and I got 2/- a week for night and morning and it was all measured out then, you know, from the kit. I was ten and there was a law came out that no milk boys had to be employed under eleven, so of course I was sacked. Anyway there was another milk chap come after me and I thought well, I couldn't go. He said, “Never mind, I'll take responsibility.” This were Frank Smith. He gave me 3/- a week and a shilling a week was a lot of money them days! So I went on for Frank for quite a while and then this wouldn't do and my Uncle Wilson wanted me back so I had to go back to Uncle Wilson so I got 3/- a week off him. This all went, I'm talking about Wilfred and me as well, it all went to me mother, we needed it. I can remember one Christmas, we used to get bits of presents off customers and we saved up all that we got. I think, between us, we got 23/- altogether at Christmas and we bought my mother a new coat. In those days, another thing that stands out in my mind when we got a penny a week to spend, we used to go into the house, into the kitchen and get the jug down and pour the milk in. This particular house, I can remember the house today, I got this jug down and somehow broke it and I paid for it. I paid for it at a halfpenny a week and it was sixpence halfpenny..

That would be an extremely long 13 weeks, Harold.

R -It was 13 weeks. I had no spending money. And they were so mean, that they took it all, every penny. I never forgot (950) who it was. I never forgot who it was.

SCG/27 November 2002

8506 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 82/HD/02

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON THE 22nd of JULY 1982 AT BANKS HILL, BARNOLDSWICK. THE INFORMANT IS HAROLD DUXBURY AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

[I must have asked how much flour his mother used at one baking]

R- I would think it would be ten pound because we used to get 20lb at once.

So the flour was in 20lb bags?

R - There was big white bags that held 20lb.

How often did she bake?

R - Every Thursday.

Did she bake cakes as well?

R- Yes.

What kind?

R - Well, I would say the ordinary bun and she used to make them in the round, flat, tins off the same mix and then she would make straightforward currant loafs or fruit loafs and currant tea cakes which were marvellous.

Did she ever make seed cake?

R - Seed cake? Yes, she'd have a go at anything. She used to make pasties and pies, you know. Rhubarb pies apple pies, onion and potato pie and of course, potato pies and what we used to call 'broth' and you used to be able to buy then, a sheep head and the sheep head used to go in the pan and there's some lovely meat on a sheep head! I could eat it and enjoy it today although people turn their nose up at that sort of thing today. There was the tongue and I can remember there was two pieces of meat which would be ½” thick to nothing, the size of the palm of your hand. I couldn't tell you where they were from but we used to do a dive for this kind of thing, you see. [sounds like cheek to me. SG.] Of course, in the broth there’d be potatoes, carrots, onions and all the bag of tricks.

Did she make jam and marmalade?

R - Oh yes.

Pickles?

A - Yes.

How about home made wine or beer?

R - No, only herb beer. She used to make herb beer. If I remember rightly it was Mason's extract.

Ah, I seem to remember that name, Masons.

R - Of course it used to get kept in these stone bottles, earthenware bottles. They'd be gallon bottles.

Did she make any of her own medicines?

R - Not really in that sense of the word, although at Christmas we used to have a goose and all the fat would be kept and stored for rubbing your chest and called goose grease. That's the only one that my mother made but my Grandmother Duxbury used to make a salve that had a wonderful healing quality and I think the ingredients, the only thing was that it was made from lard and ground ivy. That's a herb is Ground Ivy. (5 min) It had a wonderful healing quality and she used to make it and keep it in little glass bottles, Vaseline jars and that kind of thing and you know it would keep for years and it was used for years. I regret, really that I never got the full recipe of that because I think it had some wonderful healing qualities.

Oh yes, there's a lot in herbs. What did you usually have for breakfast, Harold?

R - Well, we kept hens but our breakfast would be porridge and maybe some bread and butter and if we were lucky there were eggs but there would only be half an egg each, they would be cut in two. (50) Boiled egg, cut in the middle for us lot.

What would be your normal Sunday dinner?

R - Well, a normal Sunday dinner, we usually had some kind of a joint, a roast and there’d be Yorkshire pudding and sometimes what they called a season pudding which was made like a Yorkshire pudding with onions and a bit of sage mixed in. It was really good, so we used to call it a season pudding. There'd be the usual vegetables, you see, all from the garden, no frozen peas or anything like that. If there were any peas they would be steeped, or as they call them today, mushy peas but they're still a lot better to me than...

That's one thing I find that stands out very clearly from this series of tapes is the fact that at one time vegetables were seasonal. For instance, it's possible now, to have a salad any day of the year. In those days, the days you're talking about, each thing had its season. The first tomatoes of the year were a real event.

R - But there were cabbages and turnips, even then, literally speaking all the year round because there was a Savoy cabbage which was a crinkly cabbage and they used to form a good heart and you could have them well on until the winter. Then of course, there was the Spring cabbage, turnips and swedes. (10 min) You could have them all the year round because they'd keep, you see, under proper storage conditions. I don't mean fridges, there was no such thing. You used to find a cool place and maybe cover them up with soil and that kind of thing.

What recollection have you of keeping food? When I say that, you know, we're so used to having fridges nowadays where you con keep milk five days and things like that and for instance, we were talking the other day about you delivering milk twice a day. Am I right in thinking that this was because at certain times of the year, the milk was going sour?

R - That's right, yes. Of course, it was never thought it was possible to keep. It was twice a day including Saturdays and Sundays.

So things like butter and - well you tell me, there would be things that would be loosing their quality but would still be eaten probably things that nowadays would be considered to be off would just be considered to be ....

R - Well, for that kind of thing there was a tremendous lot of cellars and there was cold slabs, stone slabs and sometimes slate. Very often sandstone slabs and they'd be built up in the cellar and they used to cure their pigs and all that kind of thing on them. They'd rub the salt into the side of bacon and all that kind of thing you see but butter and all that kind of thing, it would keep. Even today you can make potted meat and have a bit of fat on it and the fat comes to the top and it'll keep for months in a cool place because it's sealed and it's airtight and I should say that a lot of the old country folk, even today will stew a lot of meat and keep it like that in a bowl, various sizes of bowls and when company comes over bring one of them pots up, and slice off it.

What would your dinners be like during the week?

R- Well, very often something, as we called it then, broth or stew, probably twice a week, you know, or something like that. Some form of cheap meat like sheep head or ...... Anyway, that kind of thing and particularly on baking day there’d be a big potato pie. (l00) It had onions in, onions and meat, you see. Meat wasn't very expensive in those days. I was always a terror for having a go at anything and Whitham who used to be the pork butcher on where Harwood had a shop.

Aye, on Church Street.

R - Aye, well it was Whitham that had it then. He went up in the quarry, he took on the quarry [Park Close at Salterforth] but he was a pork butcher and I remember buying a roll of bacon off him. I’d be early teens I suppose, at seven pence a lb. But it was bacon you know, real stuff and maybe a lot of fat but we enjoyed fat in those days. (15min)

Of course that bacon would keep for months.

R - Oh yes, yes.

What would you usually have at tea-time?

R- Well, I can remember there’d probably be syrup, golden syrup and you used to go to the store and I can remember going to the Co-op when it was at the bottom of Manchester Road. and they had syrup. You used to take your own tin and they had the tap and it run in, you see and this kind of thing, and sheep trotters, cowheel and what was better than anything else I can remember for tea, pig foot stewed and on a big soup plate, bones and the lot and no seasoning. Well there'd be salt in them and that kind of thing but my word it was lovely!

Would you usually have any supper before bedtime?

R- No. just occasionally we might get a drink of milk and one thing I remember particularly on a Sunday night, this would be in my teens, you see and we'd go for a long walk after the chapel and we’d come home and just the same as these Spanish onions are today there’d be an onion sandwich with some pepper and salt on. My mother always used to relish an onion sandwich and so do I. Well our kids, my brothers and sisters they all did, they'd relish onions. I remember our Nora, she'd been somewhere and she smelled of onions but she didn't care.

What would, I don't know how to phrase this question really. I haven't got a question in the questionnaire about it really. What was the attitude to what is now described as 'eating between meals'? What I'm really getting at is this, would you ever dream of, in between meals, just walking into the house and going into the pantry and making yourself a sandwich or something like that? What would your mother's attitude be to that?

R- No. There was a meal time but I don't say that if we were hungry that we’d be refused something. We would get something but it wasn't a practice of diving in when we got home from school. We had to wait until tea time.

That's what I’m getting at. The fact that nowadays there's a very free and easy attitude towards children and food. Perhaps it's the right attitude but I can remember when I was young I would never dream of making something for myself. As you say, if I was really hungry and I asked, I could get something but usually it was, “You wait until your tea.''

R - Well that was the general attitude and there was a meal time and I could think, we being milk lads in those days, we would have to have our tea before we went with the milk which we had to do and I would say that if it had been severe weather or something like that there might have been something for us when we came in from the milk round, you see. (20 min)

Where did you, and I realise that to you this will sound a very strange question, but it won't I promise you to a lot of people who listen to these tapes. Where did you have your meals? (150)

R - In the living room.

Yes, and how did you have them?

R - Sat up to the table with all our own places. It was an extension table and we had the wood chairs and we'd to sit there and I used to have a habit to rock back on the chair on the back legs but I suppose all lads do but I soon got stopped o' that.

How did your mother prepare the table for the meal? Did she, as we say, ‘lay the table’?

R - Yes. There'd be a big plate full of bread and butter and there might have been a bit of cake or there might have been what we called 'sad cake' but the proper name is Eccles cake and that kind of thing. Something that was satisfying and none of these fancy vanillas. We never saw anything of that description and there was never any bought cakes at our house.

Was there a tablecloth?

R - Yes, a leather tablecloth. Leather cloth. It would probably be white or a pastel colour and it could be wiped down, you see.

Is that what we used to call ‘American Cloth’?

R- You could call it American cloth, yes. When the table was washed down and cleaned there'd be a chenille cloth put on the top of it. When we got married we had a beautiful cloth to put on the table and oh it was a lot of money! I don't know what happened to it but it were a marvellous cloth. She gave quite a lot of money for it because since I've grown up, if I've bought anything I've always wanted the best.

Well it lasted longest didn't it.

R - Well, I remember the fellow who said it to me and it was Hartley Edmondson. That's Edmondson and Co at Fernbank. He said, “Harold, the best is always the cheapest in the long run.” He worked on that principle.

You've already told me that you used to sit at the table. Did you know any families where the children used to stand for their meals?

R- No.

Did the family have a garden or an allotment?

R- Yes.

That's when you were at the Croft?

R - Yes.

Where was the garden?

R - On Butts Fields. You know where our works are?

Yes.

R - Further on there, you fork, there's one goes right along the beck side and there's one bears left and comes out into Hollins Road. Well, that triangle there, we had that triangle which is a little park, now. There were several hen pens all where the Gospel Hall is now. (25 min) We had several of those areas split up into hen pens and we had a big portion in the triangle just on the top of the rise as a garden and you used to be able to turn to the right and go down what's Harper Street now and there was a beck on the bottom. You used to have to go across a little beck there but it's drained now but this was long before Parkhurst's shop was in existence, the joiners shop. It came out about there, you see, before the road was made up and that kind of thing and it came out into Gisburn Road from there. Well of course you can remember old Monkroyd. (200)

Who looked after the garden?

R - Well, it was supposed to be my father's garden but I did a lot, I had to do. Wilfred and me, we had to do. The family needed - and of course my father, the joiners shop on the croft, you see and he was probably working all hours that God sent. Well we had to do the garden but he told us what to do. There was a fellow that used to come and help us and I wouldn't say that he taught me a lot about gardening but he taught me a lot how to use a spade. One push, no bumping, put your foot on the shovel, on the spade and down it goes - full depth, no second pushes. That was Billy Roberts, Billy Pudding. That was his by-name. The same fellow, he had the horses, the lorries. He had two lorries like flat carts, you know, four wheeled and he used to cart for the mills and they stabled down in Butts yard.

Was that those brick built buildings?

The stables in Butts before demolition in 1982.

R - That's right, yes. He stabled down in the bottom and if he'd nothing much to do he’d come up into the joiners shop and help and he was very pally with my father but I'm going to tell you now his history. He lived up the top of Park Road and he had a family, they're all dead now. Yes, he's one or two grandchildren that’s left. He was a terrible drinker: The Station used to be, you know where he was. He used to come past the Railway Hotel, and this is quite true, and there'd be a pint there waiting for him on the counter. He caught his horse, he came out at the front door and caught his horse at the other door. Going up Coates Hill before the new bridge was built he used to take a skip off, a skip of weft and carry it on his back over the hill to lighten the horse.

Over the old canal bridge?

R - Over the old canal bridge. That's true. He was a strong fellow. Anyhow, the landlady of the Railway Hotel gave him a good talking to about this drinking - the landlady! (30 min) He stopped drinking like that. He couldn't bide anybody that took drink at all. He went from one extreme to the other. I won't say he turned religious, although I dare say he might have gone to chapel occasionally. All his family did go to St. Andrew’s, as it was then, Methodist Church but all his family went there. He was very bitter against drink.

Have you any idea, apart from the landlady talking to him, why he made that change?

R - No, I never got to know what the landlady said to him.

She must have made a great impression on him!

R - She made a great impression and I’m not sure of the name, I might be wrong with this but I would say it was a Mrs Sowerbutts. Have you ever heard the name? Used to be the landlords at the Railway Hotel. Oh he was a smart fellow and I (250) might be wrong but it definitely was the landlady of the Railway Hotel and the name I’m not sure of. (30 min) I remember the landlord in the 1914-18 war but I think it was before that. The landlord was called Sowerbutts then because one thing that makes me remember, I met Sowerbutts on - I met him in Dublin and it was on a bridge, Phoenix Bridge, I think it was. Anyway, that doesn't matter.

That would be when you were in Ireland with the RFC? Anyway, the garden. What sort of fruit and vegetables did you grow in the garden?

R - Er well, potatoes, cabbages, turnips, peas, beans. I don't think we had anything of raspberries or anything like that. I can remember that my father sent me a parcel of peas, you know.

Did you eat all the stuff out of the garden or did you sell any?

R- Oh we shouldn't sell any of the stuff, it would be given to neighbours. I remember we lived at No 1 Robert Street and there was Dan Derbyshire who had the fish and chip shop at the… just below the Cross Keys in the corner there just below where Catlow had his barbers shop. Do you remember that? Well, that was a fish and chip shop and his wife looked after the fish and chip shop while he went round with the cart selling his fish and chips. (35 min) He had a fire - a coal fire in this cart and went round selling his fish and chips. He lived next door did Dan Derbyshire. Rawlinsons lived at the top house. Old Jim Rawlinson, George Rawlinson and Harold and Jackie Pomp and all that lot. [Jack Platt said that Jackie Pomp got this by-name because he was born in Portsmouth]

This is in Robert street?

R - Yes.

So you were living there while your father had the joiners shop on the Croft?

R- That’s right, yes.

Is that the house you were talking about when you said you had furniture in the front room?

R - Yes. Well, you see, it was actually Commercial Street but Robert Street branches off Commercial Street. Well all the gable end and the back door and gate was in Commercial Street but the official address was 1 Robert Street.

Did the family have any animals, you know, hens, pigs, geese or ducks?

R - Hens and that kind of thing. Hens and dogs and cats and all that kind of thing but we, literally speaking we had to have something that was productive, bringing something in, you see. Of course, my grandfather's on the farm and that kind of thing. Although I don't think we ever had much advantage from that. I never remember ever having any advantage at all.

Have you any idea how much milk your family had each day?

R - I should think two quarts.

Like a quart either end of the day?

R - Yes.

Well, you've already said that your family used butter. Did your family ever use margarine?

R- I don't think there was such a thing in them days.

It came in just at the beginning of the First World War didn't it. A lot of people didn't really - they called it ‘Butterene’ at first, didn't they? (300)

R I dare say so.

What about dripping?

R - Oh yes, dripping, yes. And the scraps. You see dripping, that's from the roast and we used to have dripping and bread and a bit of pepper and salt on and it was lovely: If there were a pig killed, you used to be able to get this sort of thing from the pork butchers and they used to cut all the waste fat up and skin and that kind of thing and pieces of fat and render it down and get the lard. There was crispy pieces of skin and remainder of fat [left]. Then there was very little fat in but then, very often, we used to get a full meal from that kind of thing. There'd be, now we’d go into the pantry and our pantry was at the top of the cellar steps and there'd be a dish of this stuff and of course we'd put our hand in and get a scrap or two out and really enjoy them. When I said we didn't get much advantage from the farm, but if they did kill a pig down there, then there'd be the black pudding and all that kind of thing. (40 min) They weren’t put in skins, they were made in a big enamel dish. We used to have that kind of thing, you know and black puddings with vinegar and mustard on they were…!

Good stuff. What sort of fruit do you think you had most often?

R - Well just occasionally we’d get an orange and apples that sort of thing but you see apples, then, I can remember you could get apples at ld or 1/2d a lb - English apples. We used to go out collecting blackberries and yes, apples from these that were almost wild apple trees. Crab apples. We’d make blackberry and apple jam.

Was that a fairly common thing, Harold, going out and. gathering stuff from the hedgerows? You know, going out for a walk and coming back with blackberries. Was that a very common thing?

R - Oh yes, yes. Particularly amongst people like us who had been brought up in the country. We used to know the places to go. We knew the fields to gather mushrooms and that kind of thing. We knew where to get them. Water cress and that kind of thing, we knew where it was. We’d no need to waste a lot of time, we knew you see because the fathers and uncles, we'd gone with them and we’d followed on, you see.

I'll just read you one or two different foods and just tell me if you ever had them or how often you had them. Bananas?

R - Hardly ever.

Rabbit?

R - Yes, any amount of them. We used to catch them.

Was that with the dog?

R - Oh yes, we used to go out rabbiting and we had ferrets and fox terrier dogs and nets.

Was that legal, Harold?

R - Well, it was legal because it was on my grandfather's farm, you see.

How about fried food?

R - Not a lot of fried food. We used to get trout from the beck. We could catch trout alright with our hands, there was no nets.

Did you ever lime them?

A - Lime?

Lime, you know putting lime in.

R - Oh no, no, no.

Any other sort of fish?

R - No.

Did your mother buy any sort of fish? (45 min)

R - Oh yes, after we came up into Barlick, of course. I think that the fish that we would mainly have would be, is it garnet? Well that was about the cheapest fish but it was quite good.

Did your mother buy it from a shop?

R - Not generally, no. A fellow used to come around with a cart, Bob Hudson. Have you heard of him?

I’ve come across Bob before, yes. With the cats following him?

R- Aye all the cats in the neighbourhood.

Tell me, Harold, how did that fish come into the town?

R - It'd come on the rail.

When you think what a perishable commodity fish was, there was really a very efficient network for distributing fish wasn’t there?

R - Oh yes.

Fish coming in from Fleetwood. I often think that the fish we got then was a lot fresher than the fish we get now.

R - Could be.

Cheese, did you eat much cheese?

R - Well, not a lot but we did have cheese, yes.

You've already mentioned cow heel and trotters and black pudding but how about tripe? Did you eat much tripe?

R- Tripe, oh yes.

Eggs, yes, you've mentioned eggs. Tomatoes?

R- Well not so often.

Did your father grow any tomatoes?

R - No.

Grapefruit?

R- Oh no, I don't think there was such a thing.

Sheep’s head of course you've mentioned. How about your mother and tinned food? Did you ever buy tinned food?

R - Well, as we got to be in our teens, yes. Not a lot but I can remember in my teens we'd come home and there'd (400) be a peach, half a peach out of a tin, you see, which was a real luxury, but that just raises another point. I told you I’d lost a brother who was five years old.

What was his name again?

R - Cecil. We used to have to walk to the Gill and my mother used to go to Gill cemetery every week and it would be over forty years that she did that and when she went to Gill, some of the family would go with her but I always tried to have the tea ready when they came home. It was no small job making the tea for eight you see, six children and father and mother and I used to try to do that. I wouldn’t say I did it every time but very often I made the tea.

How about tinned salmon?

R - That was a real luxury. There was John West tinned salmon then. I think it was John West. That was a real luxury and if I could get hold of the bones, we used to call them cheeses in those days, we didn't know it was the backbone. They all went down.

Can you ever remember tinned food being bad?

R- No.

What did your family drink? We’ve already mentioned herb beer, how about tea?

R- Oh yes.

Cocoa?

R - Not very much.

Coffee?

R - Never

Never?

R - No, I don't ever remember drinking coffee.

You've already mentioned sheep's head but can I ask you if you had a favourite food? (50 min)

R - You'll laugh when I tell you - pig feet.

That's what you said before. I like pig's feet myself. I'll tell you what I do like and you were saying about pig killing and the thing that I always remember about pig killing. I used to know a man up to a year or two back who still killed his own pigs for bacon and of course it's slightly different in these days of deep freezes but it was a job to keep all the pig meat. You used to get pig meat from really well grown bacon pigs and I used to love that. It's different altogether than pork isn't it?

R - Oh yes.

You know what I mean. It's different meat all together than the sort of pale pork we buy nowadays from young pigs that have never grown. I can understand the pigs feet bit.

R - It's a thing I never eat is pork. It makes my wife ill. I never craved for it.

Where there times when the family was perhaps not as well off as usual? If so, was there any change in the diet then? Did the meals change?

R - I never remember that it did. (450)

Aye, that's interesting. Did your father come home for his meals?

R - Yes. Not when we were down here.

When you were living at Carr’s House.

R - When we were living at Carr’s House, no. When we were living opposite the joiners shop, yes.

When you were living at Carr’s House did you used to take food to work for him?

R- Oh yes.

Did you ever take him any food?

R - No. You see he was working up at York Street then which was a fair step from here and we were at Bracewell school and then when Gisburn Road school opened we were there. My father used to take his dinner with him.

What did he take Harold?

R - Well, I don't know really. It would be sandwiches of some description, you know.

When you were at home did your father have the same food as the rest of the family or did he have something special?

R- No, my father always and mother and the children all had alike.

Do you think your mother ever went short of food to feed you?

R- No, I don't think so. I don't think she ever went short. Mother would sacrifice to make sure that we had what was necessary but I don't think she went short of food. This is one thing that I've always been very conscious of ever since I can remember. All my life I've always been very conscious of this, that anybody I had to do with, if there was any sharing out they always got a full share. I remember one time when I joined up there was a loaf of bread and the big long tables and the loaf of bread went in at one end and it was passed around the table and by the time it got to me, I didn't get any. This was going to happen again. (55 min) So the fellow opposite me, I says, “Eh, give me half of that.” “Oh no!” I said, “You're for it if you don't!” We were only kids, only seventeen when we joined up but you know you fancy yourself at that age. I know one fellow that they used to go short and there'd be two chops and they had some children but the children didn't come home for dinner but the father had two chops and the woman got none. That has always influenced me more than ever. (400) This lady had 6d and she'd three children and her husband and she'd 6d and she didn't know what to get for dinner.

Your mother?

R- I know what my mother would have got. This woman she didn't know what to get for dinner and she got two meat pies. The father had one and the other were divided, a quarter a piece for t’others.

This is of course the reason why I asked you the question. What you're describing to me, I don't think was uncommon. In your family, would I be right in saying that the attitude was that what there was was shared and everybody got their share.

R- Absolutely, yes.

This is a difficult question and it's probably a matter of opinion. Would your impression be that that was the usual thing? Was it usual for such equality in families?

R -In the majority of families, yes. There was the odd ones.

That really leads on to another question that I always ask people. it's a good time to ask it you. Looking back, what would you think that, well for a start off describe to me what your mother’s position was. What sort of a life do you think that your mother had? I’m thinking in terms of equality and opportunity, you know. What sort of position do you think your mother had?

R- Well, my mother was a wonderful person. She'd a wonderful personality and a wonderful character. I think that to some extent, my mother was ambitious.

(1 hour) My father wasn't. He was content to go on. He was a good craftsman but my mother's responsibility, I think that she felt that her responsibility was to bring up a family to be good citizens and she always wanted to live in a bungalow but she never got to. She were satisfied that her children were making some kind of headway. She once said to me, she says, “I’m proud of my family”. Well, I think she certainly left her mark in the neighbourhood at any rate. She mothered everybody round and about the area. All these old girls used to come and talk to her you know and she took them under her wing and that kind of thing.

The impression you're giving me is that she was really a very strong character and perhaps - would you say perhaps she was slightly unusual for her day?

R - I would say that my mother was outstanding character and she had within her at any rate, I think somewhere in the past she was a re-mould and I couldn't say exactly from gentry but from a bit better than the ordinary working class. Now my grandmother Gill, she did give you the impression that she was a lady! I can't say that she was or anything but as I remember her, sat in her fancy black blouse and that kind of thing you know and ruling the roost. Maybe I think that probably if I went far enough back there could be some trait - well some er throwback. I don't know.

It sounds to me as if your father made a very good choice, anyway.

R - There's no doubt about it.

Who usually did the shopping for the family, Harold?

R - We used to get a list and go and get it, these kids.

So the children would go and get it?

R - Yes.

How often did you do the shopping?

R - Generally, once a week and very often we’d have to pop on for a bit of something, you know, some of us. You see there were six of us.

Where did your mother usually buy her vegetables? (1hr 5min)

R - Very often from Sam Yates or Sam Wallace. Sam Yates had a shop in Church Street next to Harry Tinner's that's now called Colne Building Society.

Who’s there? Is it a little cafe now? Halfway House, they call it now.

R - That's right and Sam Wallace was in Newtown where Taylforth is now.

Where did your mother buy her meat?

R - Well, I had an uncle who was a butcher, my father's eldest brother was a butcher and he had the shop up Park Road.

Oh Yes. (500)

R - At the bottom of Beech Street.

Yes, that one that used to be.. [Ned Anderson in the 1950s.]

A - Simpson.

Yes, yes, that's it, aye. Simpson at the bottom of Beech Street, that's right, yes. Where did your mother buy the groceries usually?

R - I would say very often at the Co-op or from Roy Townson’s.

Where was Roy Townson's?

R - Well, it was where the 'British and Argentine Meat Company' was. That's just at the end of where Savages is. [On Church Street]

Yes, I can remember, it became Dewhurst’s eventually didn't it? Between Savages and the end shop. That’s right, I know where you mean. What would you say people's attitude was towards Argentinean meat, you know, frozen meat?

R - Oh, no, we’d never look at it. We wouldn't consider it at all.