TAPE 78/AA/1 (Side One)

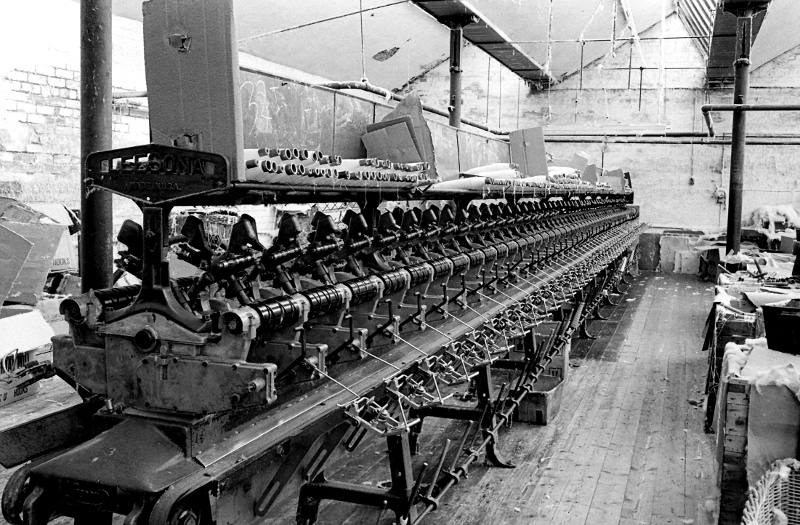

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON JUNE 19TH 1978 IN THE ENGINE HOUSE AT BANCROFT. THE INFORMANT IS JIM POLLARD, WEAVING MANAGER AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Jim Pollard in 1979.

Right Jim, how old are you?

R- sixty-two.

So you were born in nineteen…

R – Sixteen.

... Sixteen. And where were you born?

R- Cottontree, Colne.

Can you remember the address?

R- I can't remember the address at all Stanley.

No. How long did you live in that house where you were born?

R- Three months.

Three months. And .. what other houses did you live in when you were young?

R - I lived at Earby, 53 Red Lion Street till I were .. 15.

Yes. And can you remember why the family moved from Cottontree?

R - To become bakers.

Yes. So 53 Red Lion Street, was the, was that the baker shop?

The bakehouse on Red Lion Street, Earby. The back-stone that Jim mentions later on was on the inside of the gable end wall and served by the chimney above.

R- Bake, bakehouse.

Yes. So you lived at the shop? Yes?

And where was your father born?

R- Cottontree.

And what was his full name?

R - Alfred Pollard.

Alfred Pollard, And where was your mother born?

R - Cottontree.

Cottontree of course is at Colne.

R - Yes.

Yes, aye. How many brothers and sisters did you have?

(50)

R - One half sister, step sister.

So that was your mother's daughter, was it?

R - Me father’s daughter.

Your father's daughter. So he was married twice?

R - Married twice.

Do you know where his first wife was born?

R – Cottontree.

And she'd die would she?

R- She died in childbirth, at my sister's childbirth, half sister’s childbirth.

Is that right?

R – Yes.

So what year would that be?

R- Take it back, she is 75 now.

Seventy-five, so 1903. So there’s a lot of difference between you and your half sister? There is thirteen years…

R - Thirteen year's difference.

Was that very common then, dying in childbirth then?

R - Well I don’t know Stanley but that's what happened there.

Yes. And so you're obviously the second in the family?

R - That's right.

Yes. And when you were living at 53 Red Lion Street. Can you remember any relation ever living there with you?

R – No, me half sister didn’t, she lived at a place called Seacombe near New Brighton with one of me aunts.

Aye. And did you ever have any lodgers?

R - No.

And what was your father's job when you were born, when you lived at Cottontree?

R - Weaver.

Any idea where he wove?

(100)

R- It weren't Stanroyd Mill it were the mill higher up. Can't remember the name of the mill.

Aye. It doesn't matter, you are all right. And do you know if he ever did anything else but weave?

A - No he didn’t.

He was a weaver all his life?

R- Yes.

And how old was he when he died?

R - Fifty-five.

Fifty-five. And that’d be when, what year?

R - He died the same year as King George and he died a week after King George so that’d be 1935 wouldn't it? [George V died 20th January 1936 so this puts date of Jim’s father’s death at 27th January 1936.]

Aye, so when you were about to start work he died. Yes? And .. when he died, was that when you moved up to Barlick?

(5 Min)

R - No, when me father died…I weren’t keen on the bakehouse, ‘cause even when I went to school I knocked about mills. I were more inclined to go into the mill than t’bakehouse. So what we did, we had another twelve months in the bakehouse and then we moved out. [1937]

Yes. Who was doing the work in the bakehouse then, you and your mother?

R - Me mother and meself.

Yes. And what was your mother's job before she was married?

R - Weaver.

She was a weaver as well. Do you know where she wove?

R- Same place as me father but what they called it…?

Yes. It's right. It doesn't matter if you can’t remember. Did she work outside the home after she was married do you know?

R – No, she didn't.

No. And so obviously she’d look after the children, she’d look after you.

R - She looked after me.

Yes. And how old was she when she died?

(150)

R- Seventy eight.

Seventy eight? What year was that?

R - I think it’s like eleven year this time.

So that’d be nineteen sixty seven about?

R – Yes, round about that.

Roughly 1967. And … well your half sister did leave the town before. That’s it yes. Now then, the next questions are about the house and what not, and what you remember about the house. Now .. the house that you lived in as a child, you'll remember 53 Red Lion street, obviously you won’t remember anything about Cottontree?

R - I don't remember a thing about Cottontree.

That’s because you weren't old enough, that's it. Now then, 53 Red Lion Street, how many bedrooms were there?

R - Well to be [accurate] .. it were 53, 55, and 57, numbers of them houses.

Yes …?

R - Fifty seven was t’bakehouse, and 55 and 53, 55 was where t’front room was. 53 were where t’living room and kitchen was, and bedrooms. We had one, two, three bedrooms and a large bathroom. [So 57 was the bakehouse. I’ve been down there and the large fireplace that originally held the backstone is still in situ.]

Ah. So you actually lived in three houses in a way, you had three houses with the shop and the living accommodation

R - That's right, yes. That’s right.

And what sort of houses would they be? You know, what would you describe then as?

R- Terraced.

Were terraced houses. But were they back to back or…

R- No, terraced with a garden at the back, what we ...

So you'd have three gardens.

R- Well, we'd one garden but it were a big garden.

Yes that's it. And what other rooms were there? Besides these?

R - Well, which covered these three numbers and up to the bakehouse alone, we had what we could call a glasshouse built on where we did washing. And in there we had a big stove. With a gas tarred roof you know, and the old stove pipe coming through, wood floor with like an asbestos end painted with gas tar and such. And that looked out on to all this ground at the back.

(200)

Yes, so your father moved there in …well about 1916-17, during the first world war.

R- He’d move …yes, round about, aye, just after that.

Yes. When you were born, just after you were born? Can you remember any of the furniture at all?

R – Eh, what sticks out in my mind were the old grandfather clock. It filled one corner of the house nearly, to t’ceiling top. It had t’moon on with moon Phases. And I can remember the big weights. Now them would amaze me, I used to wind them up, they’d be about sixteen inch in length and happen about five inch round, solid they were. Well it were … it used to tickle me did that, winding ‘em up. And then we had a piano, and one, I can remember, one key wouldn’t play. I were meant to take piano lessons, but I would sooner be down at t’Punchbowl football field, or else the cricket field. And when I had to stay in, I might have banged the piano round and the key broke off it. Well, I’d never have made a pianist or owt like that. And I can remember two rocking chairs we had, and one had come from the old family, one were th’old grandad’s. And he had a cut out in one place on the arm, and he used to crack nuts in it, so they said, I never saw him. And then, in what we called the best room, which was number 55, we had like one of those, I don’t know, like a Chippendale suite in it, some big paintings ... Now where

(10 min)

them paintings went to I don’t know, we lost them after me mother got married the second time and she moved to Birmingham, and they were put in storage you see. So, well that’s about all I can remember of the furniture. I had no interest in owt like that and I were more for going out and …

(250)

Aye that’s it, yes. You're saying your mother married again. That was, obviously, after 1935. Yes.

R- That’s right. Roughly about eighteen months after. And then we moved up to Sough . It was near to Sough. Well you call them playing fields now.

Yes, that's it, the War Memorial at Sough. When were, what year was that?

R - Going into nineteen thirty-seven.

Yes, so that’d be two years after your father died. Yes, so that’d be when you left the bakehouse you'd go and live at Sough. But you've got to live at Sough before you came to live at Barlick. Well obviously your mother wouldn’t come to Barlick with you. I never realised that. Now you came to Barlick and your mother married and ...

R - And then they finished up and went to Birmingham.

Yes, that’s it, aye.

R - And I came to live in Barlick In 1938.

Yes, that’s it, yes. And did you ever, you know, your best room, you know, number fifty-five were it? Red Lion Street, what did you use that room for, was it ever used?

R - Really it were used mainly at Sundays. Not every week, but certain times if me sister were coming, or any relations you know?

That’s it, yes, yes.

R - And they all seemed to come on a Sunday.

And which room did you have your meals in?

R- In the, mostly in the glasshouse, you know, in what we called t'big kitchen.

And where did your mother do the cooking?

R- In't big kitchen.

Yes, in t’glasshouse. And where did she do the washing?

R - I think in the kitchen, the glasshouse.

Yes. And you've already said you had a bathroom.

R - Yes.

Now it wouldn’t be very common … When was the bathroom put in there, have you any idea?

R - The bathroom were in when we moved in, as far as .. it's always been there as I could remember.

Yes, aye. That wouldn't be very common in those days would it, a bathroom? You know like then?

(300)

R- No, same as them that lived at ... 51, they hadn't a bathroom, they used to have a tin bath. I don’t think there were anybody there, apart from us, in that road that had a bath.

Aye. Do you think that was perhaps because it was a bakehouse? One of the reasons why?

R- I should think so, that's the only thing I can put it down to.

They'd be a bit better off and they had the room so…

R- Yes, that's right,

…they had a bathroom. Aye. And when you were a lad did you have a special bath night?

R - Bath night, special bath night were always Friday night.

That's it aye. It’s funny, it nearly always was, aye, yes.

R- And everything had to be, a complete change from t’vest onward you see.

That's it, aye, how about the lavatory?

R - Lavatory? It was in with, where t’bathroom was.

So it was an inside toilet

R - An inside toilet

And did it have a tippler as well outside or they'd have it done away with it?

R - We had no tippler.

Ah .. yes.

R - Only thing I remember about a tippler were me sister at Cottontree.

Yes. That’d be a tippler there. There were a lot of tipplers in Earby, we had a tippler at Sough. And obviously the house would have piped water?

R – Yes, we used to have the big cistern cupboard even then, where t’toilet and t'bath were.

So you had a hot water system, as well.

R - Yes.

And what was that from, a back boiler?

R - Back boiler.

About the bakehouse itself. What was the oven in the bakehouse?

R- What, we’d got what you'd call the backstone which were a built up brick thing, with two big thick pieces of iron where you make crumpets and oatcakes and milk cakes, muffins.

That's it, and .. how was that fired.

R - Coal.

Coal, so it was a coal fired oven.

R - Coal fired oven.

Did your father over put turkeys in at Christmas for people? And such as that, did he ever… Some bakehouses used to didn't they?

R – Well, they'd have a job putting them in Stanley because you did all your baking on the top of them flat iron plates.

It wasn't enclosed?

R - Oh no, no it were open.

So you weren’t actually baking like.

R - You weren't baking bread and such as that, you were just baking oatcakes, milkcakes, muffins, crumpets.

(350)

Aye …Ah I see yes. [At the time I knew nothing about back-stone baking and didn't really understand it. I later found it was very common in this area and the main products were oat-cakes and muffins, all baked on the thick iron hotplate like a very large griddle.]

R - Which seemed to be the thing in them days.

Yes. Well I suppose a lot of people’d bake their own bread wouldn't they?

R - Me mother baked her own bread in the gas oven which we had in the kitchen.

Yes. Now that's it. And the shop, did it have a shop window?

R – No. It didn't have a shop window Stanley. He used to hire men to come and take this stuff out you see, in baskets.

Oh so you didn't sell it from the shop so much, people, obviously some people would come to the shop,

R - Some'd come to the shop that wanted some, you know, but…

But most of it'd be sold out in baskets ...

R - In baskets.

Round the houses?

R - Yes.

Aye … that’s interesting, I didn't realise that. Was that uncommon then do you think?

R – No, it were common because there were, there were another baker that did t’same thing in Earby as what we did. Then you got them all round Nelson doing that. At one time I used to pedal an old bicycle to Barlick and they used to come with a basket on the front. I used to have a carrier at t’front on me bike and I used to put a basket in there and I used to bring oatcakes and muffins and crumpets to Wallace Horsefield’s the pork butcher.

Whereabouts was his shop?

R- Bottom of Park Road which is now Penny’s, Chemist.

Penney's, which used to be Wallace Horsfield's butcher's shop is the white building on the left.

That’s it, yes. And can you remember where your father got his flour from?

R- Well there used to be Greenwood’s and Appleby’s then, and they used to bring it straight to the bakehouse.

They were millers?

R – Millers, yes. And where did they come from? Whether we, where they come from I don’t know. Preston or thereabouts. Used to come on their wagons.

That’d be delivered by motor lorry?

R - Aye and he used to have Greenwoods for one certain type of thing and Appleby’s for another. And then there used to be another’d bring your oatmeal from somewhere else.

Aye. Can you remember any of the prices that they used to charge then?

R- Oh I can’t Stanley, happen three ha’pence for a muffin in them days, a penny for a milkcake …

Aye. No that’s all right. Yes.

R - Or you’d get an oatcake with a penny, and you get thirteen if you got a dozen.

That's it, the baker's dozen.

R- Well I don’t know about the baker's dozen or not but .. you used to get thirteen.

Aye, that's right.

R - And we used to sell a lot to pubs, oatcakes, in them days, and

400).

they used to put it on a rack and it used to harden off and they used to sell stew and hard.

It's stew and hard. [Stew and hard was still common in the early sixties. I used to eat it regularly at the Craven Heifer in Kelbrook.]

R - Somebody didn't like stew they'd sell 'em some of this like New Zealand cheddar or sommat like that and onion on, cheese and hard.

Aye, that's it. Now then, back to the house itself Jim. Did you have a stair carpet?

R – yes.

What sort were it?

R – A narrow one, it wore red and blue. I think anybody that had a stairs carpet in them days, they were all t’same type.

Aye ... And do you remember any of the neighbours having a stair carpet?

R – Yes… I can't really Stanley, we must have been posh in them days. But we couldn't afford a stairs carpet what went up to the toilet, because, to t’bathroom, because it you come out of the bath we hadn't to have us wet feet on't carpet.

Oh, is that right?

R – We’d linoleum or oilcloth as they called it in them days.

That's it, aye. And what other floor coverings did you have on the rest of the floors in the house?

R – Oh, in the house?

Well, like when I say in the house, you know, in the … well say in the bedrooms.

(20 Min)

R - In the bedroom? We hadn't, we had just a small, what …pegged rug we used to have.

Yes, a pegged rug.

R - At each side of the bed was covered with oilcloth, linoleum.

Yes. And downstairs?

R- Downstairs we had a carpet on top of oilcloth, just square carpet.

Yes. And what kind of curtains did you have?

R- Curtains?

Yes.

R - Well we were, they were sommat similar to what they're coming back with now, but instead of being this fancy brass, they were like a wood with blooming big hooks on.

Yes… Yes, and did the neighbours have curtains as well?

R - Well, they’d either curtains or blinds..

Yes. What sort of blind?

R- Them that they pull up and down, paper they were.

That’s it, yes, spring blinds yes. And can you remember any families in Red lion Street not having curtains?

R- I can remember Alice Green next door, she had none.

No curtains at all?

R - None.

She didn’t put newspapers up at t’window?

R - Well, she would do if…

No, go on…

R - Well she put, you allus knew if there were a caller there, because she would put newspaper up to t’windows and he used to try and float out when it were dark, you see, but everybody got used to this.

(450)

Oh I see, so she was, she was tolerated.

R - Yea, she were tolerated.

Aye, aye .. and did they, women in the street, did they donkeystone the doorstep?

R - Well they used to put this here, give 'em a good scrubbing and then they'd come with the donkeystone and white edge ‘em. And .. that were on the step going into the house, but on t’window bottom they might do a bit different, they might just put a bit of yellow stone on t’bottom side and white edging at the top.

That's it, hard and soft. And .. how about the kerb stones, did anybody do, edge the kerb stone?

R - No.

No. And how was your house lit?

R-Gas.

Gas. And can you remember when you first had electric light? In Red Lion Street?

R- We never had electric.

You never had it while you were there. And how about the household rubbish, how did you dispose of it?

R - Well we used to burn a lot, but such an cinders ... I've forgotten how they were collected, I never remember dustbin men coming ... I can't even remember us having a dustbin!

It's all right, don’t worry about it. How did your mother do the washing?

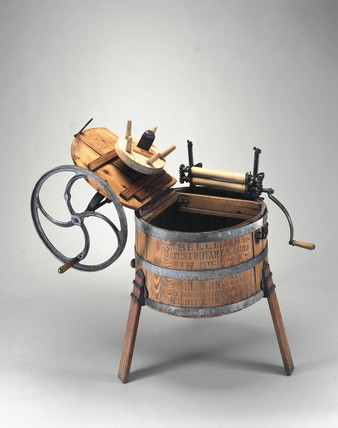

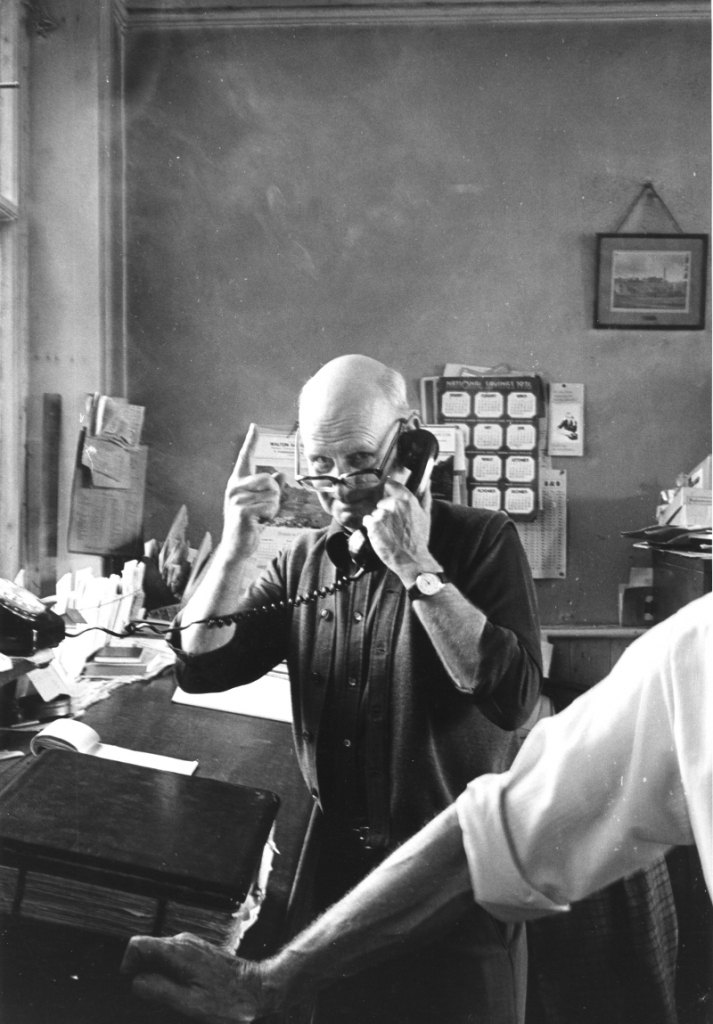

R- Oh. In an old possing tub, I know there were wood rollers, and we used to have a boiler, gas boiler, she thought they were better, they'd come cleaner if they were boiled a bit.

That's it, boiler ...

R - So she took out of ‘em, and then put them in this wood machine and give them a spin you know wit' .. she had like a spinner which she did wheel around, and rollers were attached to this you know. So she gave ‘em a spin with this with a handle and then off with the lid, picked one end up and what we called mangled it through them wood rollers. And to alter the pressure, she used to have two tensions at t’top which she used to screw down

That's it, that was like a sort of washing machine.

An early hand-washing machine like the one Jim is describing.

R - Washing machine yes ...

That's it, yes. How often did she do the washing?

R - Twice a week.

Twice a week. And how long did it take her?

R - Well I couldn’t say Stanley, I weren't interested in such as household chores in them days really.

No. It's all right. How did she dry her washing?

R- Well in this ground we had which was attached to this … at the back.

Yes. And if it was wet?

If it was wet we used to have ‘em up against this stove, on what we used to call an old clothes horse, wood thing

(500)

Aye, clothes maiden, aye. And how did she iron her washing?

R - She used to heat her iron on t’gas and then she used to rub it on a rag.

Yea, so you mean they were flat irons and she used to heat them on the gas stove. That's it, she'd have a couple going at once. She didn’t use a box iron or a gas iron then?

R- No. I can remember I think we had a charcoal iron at one time, but she didn’t to a bundle on that.

Aye, she’d rather do 'em on all…

R – She’d rather sit ‘em on t’gas you know?

What do you remember most clearly about washing day? Is there anything that sticks out in your mind about washing day?

R - Well, only when I were getting older. She used to play heck about me cricket pants, they took a lot of mucking about with you know?

Aye that’s it. Grass stains?

R - Grass stain, green stain which took a lot of moving.

Aye. Oh, you had whites then?

R - Oh aye we had whites. We even had whites when we were at school, for cricketing.

Did everybody?

(25 Min)

R - Not everybody. Well, biggest part’d have a white shirt, and grey flannels. So we’d have our own flannels. But in them days if somebody were interested in the cricket team at school…his wife, the teacher's wife, would even, I've known her even buy a cricket shirt for a lad if he hadn’t one, they were that interested in the school team.

That was the wife of the school master.

R- Not the school master, one of the school teachers which were like games master.

Yes, that's it, yes. And how did your mother clean the house?

R – Well, she used to, they used to have one of them there sweepers what

you pushed it. What do they call them?

Ewbank?

R- Ewbank, that were it, that were t’name of it, Ewbank, yes.

Ewbank, yes.

R - And then she did the dusting t’normal way of dusting but she used to have a feather brush and all which seemed to be one o't doings that’d come in handy if she wanted to thump me now and again.

Not so bad it she were hitting you with a feather brush. Was there anything that she paid special attention to when she were cleaning the house ?

R- Well…

You know, any piece that ...

R – Furniture? Oh aye the piano and grandfather clock.

Any idea where the grandfather clock came from?

R - Oh, he’d been handed down for years. It were one of Old Pollard’s ... what do you call it?

On your father's side?

R - On me father’s side.

Were your father the oldest son do you know?

R– Yes.

Yes, because there used to be a tradition in this area, and I know that the clock was handed down to the oldest son.

R - but he had older sisters.

Yes but it… It did use to be the eldest son. And did you, and .. well, did you ever do any jobs in the house? Did you have any regular job that you had to do?

(550)

R – No, sometimes I had to mangle for me mum, turn t’mangle or feed an hen or two which we had on this ground at t’back.

Yes, you had a few hens out the back. Did you have any jobs to do outside the house you know like running errands or gardening apart from feeding the hens?

R – No, we never run .. we’d no garden at t’front Stanley, it were just flags and …you know.

Yes but I mean at the back you know?

R – No, we didn't have no garden at t’back.

You didn’t garden it no.

R – No, it were grass which were made into a cricket pitch.

Did your father do any work in the house?

R - Oh no, nothing at all.

Nothing at all. No.

R - Me father were one, as soon as he’d finished his jobs he’d have happen an hour’s sleep after tea and then he’d wander across to the Red Lion, which were only about ten yards from where we lived.

That’s it.

R - And that were his regular routine six nights in t’week, but he never went at Sunday.

He never went at Sunday.

R - I remember my mum used to say “I’ve never seen him come home drunk.” He’d come home a bit fresh, but never drunk.

Did the family own the house?

R- Yes.

Yes, have you any idea how much they paid for it when they bought it?

R- I haven't a clue Stanley.

Haven't a clue. Did your mother ever do anything, any work in the house to earn a bit of money for herself? You know?

R - No.

Nothing on the side. Do you remember if any other women in the neighbourhood did anything like that, you know, like taking in washing, or minding …

R – No, somebody might have looked after a child or two you know? Yes..

Yes, for those who were working at the mill, yes child minding.

R- Some of ‘em that lived up there’d be off out with the children at half past six to go in you know? Start work at seven.

Yes, in the mill, yes. Is that house still standing?

R- Yes.

And what did your mother cook on?

R- Gas stove.

That was outside in the greenhouse, glasshouse, glasshouse, yes.

R- In the glasshouse.

Did she have that gas stove when she first went there?

R- When we moved in it were there.

Yes. Can you remember anything about it?

R - Not a thing Stanley.

Ah .. And she made her own bread in the oven.

R - She made her own bread.

And how much did she make at a time?

R - I should say me mother baked every two days so as it were nearly always fresh broad, you know?

Yes. Did she bake cakes?

R - She used to bake sweet cakes. Yes.

What sort

R - Well, she did her own, you know like ... I should say they'd be cream cakes Stanley, you know? Baked in a … what's that there? six inch tin or eight inch tin and then put one on top of the other and make it into a great sandwich.

(600)

(30 Min)

How about fruit cake, seed cake and what not

R - Well she'd make currant cakes you know, just ordinary, t’same mixture but they'd have currants in and put in little bun tins and…

Pies .. ?

R – No, she used to make a lot of Eccles cakes or jam pasties and..

How about jams, marmalade?

R – No, she never made owt like that Stanley.

Pickles?

R - No.

Homemade wine ?

R - No.

Did she ever make any of, any of her own medicines, you know ...

R - Oh give over, she was a big, big believer in t’herb job, brewing this up and brewing that and …

Oh, yes, yes.

R – Holland’s Dutch Drops, she didn’t make them, but they could buy ‘em and they 'd cure all.

What were those? ..Holland?

R- What they used to call Holland Dutch, Holland Dutch Drops in them days.

And what were them for?

R - All aches and bloody pains you know. Same with Fenning’s Fever Cure, used to be all t'go, that were always in t’medicine cupboard. And then she’d be on with the Nipbone if I had any bruises.

How did she get them herbs, did she go out and gather them herself?

R - She used to go out and gather a few aye. There used to be old herb books in them days and so she'd go out and…

And what did you usually have for breakfast?

R - Well that's something which we never had, we never had breakfast.

So you didn't bother with anything in the morning or … ?

R- We didn't bother with anything, Stanley.

Nothing at all?

Nothing at all, only a drink

Drink and straight on to school?

R - .. which was tea.

Tea, yes. What did you have for dinner?

R- Sometimes we had nothing. I’m going back to school with just a tea cake in me hand.

Aye. How about Sunday dinner?

R - Sunday dinner? Well we’d a roast you know, a meal then a proper dinner, Yorkshire pudding, meat…

Every Sunday, Yorkshire pudding?

R - Not every Sunday.

No. What were the usual meat?

R- Beef.

Beef.

R – Aye, me mother didn’t like smallish ..mutton or,.. tha knows lamb, didn't like, didn't like mutton, beef, lamb. Pork were a bit of a favourite.

Aye, crackling.

R- Crackling.

Aye. So during the week you wouldn't have so much for tea?

R- Well, we’d a big tea, and then we were always late in going to bed and we always used to have a decent supper.

Aye. Yes, what would you have for tea say, you know, what would you call a good tea?

R - Fish.

Fish?

R - Fish, and potatoes and funny enough we’d always a chip pan, what we call a chip pan now, such as that. Or sometimes, I can, I can remember

(650)

odd times we used to have a damn big dish in the middle of the table with mussels in or cockles and you'd have a basin full of mussels, one of cockles and then you’d have another basin to throw your empties in, yes.

It, there seems to have been quite a lot of fish and cockles and mussels eaten then.

R – Well, they were cheap enough Stanley, weren't they?

Yes. And .. did somebody come round selling fish and .. ?

R - Well, they used to come round on an old horse and cart. We used to have a fellow called Laurie Nichol come round, he used to have a wooden leg, and he used to sell a lot of this. And we used to have a bull mastiff and that were its favourite do to get at, try to get hold of his wooden leg when he used to have It stuck out on't cart'

He didn’t by any chance have cats following him round did he.

R – No, I couldn't say.

No, have you any idea where that fellow got his fish from?

R - I haven't a clue.

No, most likely coming by rail, wouldn’t it?

R - 1t’d come .. yes.

Yes, to the station yes. And your supper, you say that very often you had a good, good supper before bed time, what would you have?

R – Chips, fish, peas … we’d … usually it'd be chips fish or sometime me mother would make a meat and potato pie. You see, they'd more time after, say round about three o’clock at the afternoon.

That's it yes. Your mother’d normally help your father with the baking would she?

R – Yes, me mother and father did it.

Yes so .. that's the reason why many a time you didn't get a dinner because she had other things to do.

R- Other things to do in the bakehouse.

(35 Min)

SCG/09 October 2002

5507 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 78/AA/1 (Side Two)

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON JUNE 19TH 1978 IN THE ENGINE HOUSE AT BANCROFT. THE INFORMANT IS JIM POLLARD, WEAVING MANAGER AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Now you've already said that you had a garden outside but you didn't garden it, you didn't cultivate it. So you wouldn't have, did you have an allotment?

R- No..

Did you have any hens, pigs, ducks, goats, owt like that?

R – We’d about ten hens, a cock, sometimes we might have a few pigeons. I once had a goat but it stunk so I had to shift it.

And what did you do with the eggs?

R – Well, me mother used to bake with ‘em and we used to eat them, fry ‘em.

Yes, that’s it.

R- Boil ‘em.

Yes. And you’d, if any of the hens went off a bit you'd…

R - Well you see, it all worked in with what we had left out of the oatmeal. It meant food for the hens, mixing it up, hot mash.

That’s it, so the waste out of the bakehouse went to the hens.

R - Went to the hens and we got the eggs. When they'd finished laying, finished their span of life, that were it, we'd get another ten.

Did you have a pudding every day, at tea time with your tea?

R - Yes. Favourite were, they used to have these here jam rolls, in rags, and steam them.

That's it, suet, Yes,

R- Suet. Or sometimes we’d have what we used to call ‘Eve’s Pudding”. Made out of, nearly a cake mixture with apples in it, at the bottom, with custard.

How much milk did you get each day, can you remember?

R-About two points. We used to get it at the farm, out of the tins, ladle it into the jug.

Lading tin, aye. Did your father ever get any for baking?

R- No. What we used to make the milk cakes were buttermilk.

Did you get that off the same farmer?

R- No we didn’t. We used to go down to Booth Bridge at Thornton. Sometimes I’d walk it. I had a tin on me back, strapped on.

Aye. A back kit.

R- Back kit. I’d go to Booth Bridge and they made butter there.

Were it Wilkinson’s?

R- Wilkinson’s. It’s Wilkinson’s yet. Run by the sons. And I’d go there and collect this buttermilk. And sometimes you get a milkcake and it might have a funny, distorted in the middle but that’d only be because there was a bit of butter left in the buttermilk.

How often did you go for the buttermilk?

R- Once a week.

Once a week. And did your mother ever buy butter, margarine, dripping, any of these?

R- Butter. We never had margarine. Never.

Why not? Do you know?

R- I don’t know. We never had margarine in that house.

Aye. Do you think perhaps your mother had something against it? Or your father?

R - I don’t know. I haven’t a clue but we never….

Never had dripping?

R - No dripping,

No dripping?

R- No.

So your mother baked with butter.

R- Me mother baked with butter.

What fruit did you eat most often?

R – Apples, bananas. Not a lot of oranges, they didn’t seem to do for her, but apples or pears and we used to eat a lot of plums when it were plum time you know?

Yes. Where did you get your fruit from?

R- Greengrocers used to come round with a cart, some of them used to come from Colne, what you call Cheap Jack. There used to be Harry Hart from Colne. And it, Hart, it used to be surprising how much cheaper his fruit were than what you could get it for in….

Hart? Aye ... what were the usual fellow that come round Earby?

R- Well mostly it were the Co-op greengrocery van that used to come round.

When you say a van, was that a motor van?

R- Well no. It were built up like a van but it were pulled by a horse.

Aye, that's it, something like an old milk float.

R - It were like a van that were cut out to have his fruit on display you know.

Yes. What vegetable did you buy most often?

R- Potatoes

Apart from potatoes?

R- Carrots, Cauliflowers, not a lot of cabbage.

(150)

(5 Min)

There’s a list of foods here, and I’ll just tell you what they were. Can you tell me whether you had then every week or once a month or very rarely or never? Bananas?

R- Every week.

Rabbit?

R – No.

Never?

R- Never.

Fried food?

R - Fried food? What’s that?

You know, fried food, stuff fried in the frying pan. You know, fried bacon, chips, owt like that. Anything fried in hot fat.

R - Bacon, yes bacon, chips

Aye .. Fish?

R – Fish.

What sort of fish were it usually?

R- Well we used to got hake, halibut, plaice. We never liked cod or haddock.

Must have been well off. They'd be dearer fish then wouldn’t they?

R - They were dearer fish but they seemed more wholesome you know?

Yes, cheese?

R- No, we didn’t eat a lot cheese, mostly if we got a little bit, it wouldn’t be so much, it’d always be Cheshire.

Aye . How did you eat that? How did it usually get eaten, do you know?

R- Well, we used to eat it with pickles, and…

That’s it, yes. Cow Heel, tripe, trotters, black pudding?

R - Yes we used to have it, and we used to have a bit of tripe but it always had to be seam with no fat on. And then me mother used to get cow heels and she used to make potted meat with cow heel.

Aye. Eggs obviously, you had your own eggs. Tomato?

R- Tomatoes when they were in season. And a fellow that lived higher up Red Lion Street used to have a lot of them greenhouses.

(200)

Can you remember his name?

R - Lodge. Louis Lodge.

Louis Lodge. Grapefruit?

R- No.

Sheep’s head?

R – No.

Did you ever have tinned food?

R – Very seldom Stanley.

If you did have it, what sort was it?

R- Peaches.

Peaches. Were they halves or slices?

R- Halves.

You must have been well off! Can you ever remember having tinned food and it was bad?

R-No.

Aye. Apart from peaches then, your mother wouldn’t like other tinned foods?

R - No, we used to have other food when they wore in season such as strawberries and …

Yes, that's it.

R- A few raspberries and then me mother used to bake a lot of bilberry pies and goose bob pie or rhubarb pies.

Where would you get fruit like that, you know, would you get it? Did you get it from a shop or off the cart or ... bilberrying, do you know, did you go picking or what.

R - Well you got a lot of folk going picking them and then selling them to make a bit of spare money.

Now then …

R- Same as stuff such as watercress. That’s what you’d have a lot of.

Yes, well, somebody that was very hard up, and stuff like that was in season round about. They’d go off and say pick bilberries on the moor and then come back and sell what they picked round the town.

R - Come back, that's it, and sell what they picked, that made them a bit of beer money.

Yes. Was it usually the men that did that?

R- Mostly the men.

Aye .. What, out of work or what?

Out of work.

(250)

For beer money.

R - For beer money.

Yes. Did you drink tea, coffee, cocoa?

R- Never coffee, [we drank]tea. Never cocoa.

Yes .. Never cocoa. What did you have for Christmas dinner?

R – We’d always a turkey.

Always…

R – Always.

Where did that come from?

R – Well, it come off a farmer.

Same one every year or …

R- Yes.

Who were that?

R – Wilkinson.

Booth Bridge?

R - Booth Bridge.

What was your favourite food when you were a lad?

R- When I were a lad? Well me favourite meal would be chips and halibut and some fresh garden peas.

(10 Min)

Was there ever a time when, can you ever remember a time when the family were hard up?

R - Well I didn't seem to notice it, Stanley.

And obviously your father’d be, all the meals your father had'd be at home because he was working at home ... Did your father always have the same food as the rest of the fondly, or did he ... ?

R - He used to have the same, well everybody used to have the same food Stanley.

That's it yes. Who usually did the shopping in your family.

R- Me mother.

How often did she do it.

R - About … happen twice a week, but she used to have a lot… You see, with carts coming round you didn't, you didn’t need to do the same shopping Stanley.

How about meat?

R- Meat. Yes, we used to get that at Edmondson’s which is at the bottom of Riley Street Earby, He used to have a butcher’s shop there.

(300)

And how about the groceries?

R- Well, t’grocery, we used to go to the Co-op for the divi. You might get half a crown in the pound in them days.

So they were members.

R- We were members at the Co-op.

Yes. How much were it, being a member then, can you remember? You had to have so much in didn't you.

R- You'd to have a pound share in t’Co-op in them days.

That's it. Was there a market in Earby? You know, an open market?

R- I can’t remember one Stanley.

No. Was there any difference would you think, in… did you have a local corner shop?

R – Yes, it were a house shop, which was in number 49.

Red Lion Street.

R- Red Lion street.

Who kept that, can you remember?

R - A Mrs Eastwood, Lois Eastwood they called her, and she'd a son and a daughter, and Vic Eastwood, the son, he were keen on the Isle of Man TT.

So what did she sell at that shop.

R- Oh sweets, a little bit of butter, sugar, tea, coffee, washing powder and all such stuff as that.

Yes. Donkey stones?

R – No, we’d to go [for them] to the shop which were… It’d happen be about 37 Red Lion Street, which were a bigger shop you know, and they’d sell bacon, and you'd get donkey stones there.

Who kept that shop?

(350)

R – Slater’s, they called them Slater’s and they did a bit of their own baking and all, such as bread and tea cakes, th'old, what you could call the old type fancy bun you know with t' middle cut out and a bit of this here butter cream in.

That’s it. So that’d be oven baking, yes?

R - That were oven baking, yes.

And would you say there was any difference in the prices that they charged in the little corner shops down on Red Lion Street and say the Co-op?

R – No.

And did the shops on Red Lion Street, would they give credit?

R- Slater’s wouldn’t, but Mrs Eastwood would.

Yes. So if somebody were hard up they could …

R - They could strap.

Yes. They'd have a …

R - They'd have a book, and could cope. They called it strapping in them days. So she’d have it booked down in a small book. Happen for Mrs Taylor, owed so much. Some were never straight, as soon as they got paid from the mills at Wednesday they’d go and straighten that off and then she .. like, suppose it were Mrs Taylor, she'd be at it again. So she is actually never straight, she is still owing money, she's always a week behind.

And a tied customer, yes. Can you remember ... was there a pawn shop in Earby?

R- Well, you could call it a pawn shop, there were Levi’s at Earby, a Jew. Isaac Levi.

Yes. And would he take pledges, you know, take stuff in and …

R- He’d take stuff off you, yes.

Give money on ‘em and then you could go and get it redeemed?

R- And give money and then you could go and get it redeemed if you wanted.

Yes. And whereabouts was that?

R-That were on Victoria Road.

(400)

Yes. Whereabouts, any idea?

R- Oh, what do you call it? There’s a bank at top now isn’t there?

Yes.

R - And then two houses, and there’d be the shop which is Banham’s cycles which used to be Simmonds, electrician after Levi finished with it. Well he used to be in theer did Isaac Levi, and he used to sell furniture and linoleum and …

Can you remember anybody .. anywhere round about, lending money for interest?

R – It’d be Isaac Levi.

He'd lend money as well?

R- Yes.

Aye. Any idea what sort of interest he’d charge?

R – No. I haven’t a clue Stanley.

No. Any idea what he charged on the pledges?

R - Not a thing.

No. So, obviously your family'd never use the pawn shop?

R- No. They used to go there and buy furniture because he kept a good quality, he used to keep some good stuffed furniture.

(20 Min)

Yes. Was that new or stuff that he’d taken in pledges?

R – New.

So he’d be the furniture shop as well as being the pawn shop. Did you know if any of the neighbours used the pawn shop?

R- Alice Green.

Her with the newspaper?

R- With the newspapers.

And the money lender, do you know anyone that used the money lender?

R- I don’t Stanley.

How about Provident cheques, can you remember?

R- A man used to come round with these Provident cheques. And you could go to Isaac Levi who were on Provident. And then there were… what were the other shops in Earby? You could take them cheques to them shops and get what you wanted you know, and then they'd have collectors coming.

That's it. What did they use to call the collector in Earby, can you remember? Have you any idea what they used to call him?

R - No I don’t know Stanley I don’t know.

And had you a name, did they have a name for him?

R- They used to say "The Man from the Provident’s coming."

That’s it. ‘The Man from the Provident’ No, the reason why I ask, some people call ‘em ‘The Tally Man’ you know.

R- Yes. We used to say ‘Man from Provident’.

Did your mother ever use Provident cheques?

R- No.

Have you any idea how much it’d cost your mother, you know, how much housekeeping money your mother would have for a week?

(450)

R- I never knew what me father gave me mother for housekeeping.

Is there anything that you used to eat when you were young, which you can't get now?

R- Well, I can't get such as fish that I prefer, which is too dear now, such as halibut, white hake. So what we have to do now is to go on to a bit of plaice, we change about, plaice and haddock, which really and truly, haddock I detest.

So you think really that fish is dearer now, compared to what it was then, even taking into account the difference in the value of money?

R - Yes

So in them days you'd say that fish was a fairly cheap food.

R- Yes well we always had .. we weren't a very well off family Stanley, we were a careful family in the main.

That's it, yes. You'll not remember anything about the first world war, obviously because you weren’t old enough.

R - Weren’t old enough you see no. But why me father came out of the mill and that was because he was gassed during the first world war.

And he was away at the war and he was gassed?

R- Yes.

That’d be chlorine gas though, he’d be bad with his chest.

R- Terrible chest, that eventually was what helped him to die at an early age.

Yes. How old was he when he died?

R- Fifty-five.

Fifty-five, that wasn’t old was it? Did you, did he, when he was gassed, was he invalided out or did he finish the war?

R - He finished the war.

He finished the war even though he’d been gassed. Yes, my father was the same. So he’d be prone to bronchitis.

R – Aye, it were a terrible cough. He finished, he died with what they called in them days ‘Silent Pneumonia’.

Yes. And do you know if he over drew a disability pension through being gassed?

R - Not a penny.

Never drew anything. And when he did eventually die, it was never put down as the results of war injury? Your mother never got anything then?

(500)

R - No, not a cent.

No, did your mother make any of the family’s clothes?

R – Well, it might be a laugh. She used to make me all me vests, wool knit vests.

She used to knit them?

R- She used to knit them yes. Apart from that she'd make me an odd shirt sometimes you know.

Was there any particular reason for her knitting wool vests for you, you know, did she regard you an a delicate child?

R- Well I wouldn't say I were a delicate child, but she made certain that I were warm.

Aye, that's it. Did she have a sewing machine?

R- Yes.

Do you know what sort it was?

R - A Singer.

A Singer treadle ?

R- Treadle, two feet on and going like the clappers

And did she mend your clothes?

R- Yes.

Was she good at mending clothes?

R- Quite good with patching.

Yes. How about darning?

R - She didn’t like darning socks but she did it.

She did it, mushroom?

R- Yes. And a biggish needle.

Biggish needle, yes. Did you have any passed on clothes?

R- Never.

No. And so your clothes would be bought. Where were they bought?

R- At t'Co-op or at Maynard’s at Earby.

Yes, Maynard’s, it isn't long since he went out of business is it, the old fellow? I can remember going to Maynard’s, yes. ' What happened to your old clothes?

R-I think me old uns would be old uns Stanley ‘cause I were a bit of a rough un.

So what, rag and bone chap?

R - Rag and bone chap. She’d give stuff to t’rag and bone chap to get donkey stones for the steps.

A rag and bone man in Salford in 1977 but exactly the same as Jim remembers.

What did you wear for school?

R – Grey, short flannel trousers. I wear , what do you mean, school? At t’beginning or when I got .. going up into twelve, thirteen?

When you, when you first went to school

(550)

R - When I first went to school? Oh, like a tight little, tight short pants, and a jersey and some clogs, small clogs, and I can remember going, which I shamed with, a blooming wool scarf wrapped round me neck and fastened at the back with a safety pin.

Were your clogs ironed?

R - Ironed. I used to get them done at t’Co-op, Earby Co-op, and a fellow, called Lord used to be t’clogger there.

What was his Christian name? Can you remember?

R - Can't remember. But one of his sons lives in Barlick now, Frank Lord, he used to play cricket with Barlick. His father did all the clogging at Earby.

What sort of irons were they, were they ordinary irons, or Colne irons or what?

R - Ordinary irons, ordinary irons.

Could you get Colne irons in Earby?

R - What's Colne irons?

You know, haven't you ever seen Colne irons, they’re thick irons.

R - These were thick uns. So they lasted longer.

Yes. Were the irons, the clog irons that you used to get, had they a groove down them?

R- In't middle, in't middle of the iron, he used to groove them all round and then he used to knock nails in. Nearly like a blooming [horse] shoe they were.

Yea. No, Colne irons are a lot thicker. And this clogger, Lord, at the Co-op, did he ever make clogs?

R- Yes, out of a wood block, from a wood block.

He made him own soles?

R- He made his own soles, and then he shaped his own leather.

Yes. Did you actually see him cutting his own soles? Or did he buy the soles in, already cut? Do you understand what I mean?

R- I’ve seen him, I’ve seen him make a pair of clogs out of a block.

Yes, that’s it. Did he use a knife on a bench that were hinged on?

R- It were hinged on in like a loop at that side and it were a big thing and he’d be ...

That's right, that's right, yes.

R- It reminded you of a scythe at one end.

Yes that’s right Jim. Now that was when you first went to school. Now when you got a bit older at school, what did you wear then?

R- Grey flannel trousers and a shirt, but I still wore clogs.

Yes, still wore clogs.

R- Because we couldn't afford a ball to play in the school yard, so we used to kick a stone about for footballing.

Aye, did you have any shoes?

R-I had shoes yes, and I used to got them at t’Co-op, but me best pair were made at Newton Pickle’s at Kelbrook. He used to be the shoemaker there.

Yes. When you say Newton do you mean Johnny Pickles’s brother?

(600)

R - No. I don't know whether they are related to Newton Pickles.

Yes they are.

R - Are they?

Yes, that’s why Johnny in buried at Kelbrook.

R - Kelbrook is it?

Pickles were cloggers at Kelbrook and his brother [Johnny’s]was the clogger.

George Pickles, cobbler at Kelbrook.

R – Well, this were Newton, and sometimes he’d be off on a drinking spree for a month.

Yes, that's what.

R- Take his hook. There used to be about six of them. And every twelve months they used to have this month off, and away they'd go and nobody knew where they were. So somebody's shoes would be happen waiting to have a pair of soles and heels and they’d be without shoes for a month.

And what kind of hat did you wear, did you wear a hat?

R - A cap, I used to wear a cap.

Aye, with a badge on.

A - With a badge at t’front

Aye. What were that?

R - Alder Hill School

Alder Hill School. What did your father wear for work?

R - For work?

Yes.

(30 min)

R - Well he used to wear an old pair of pants, an old Union shirt, and to hold his pants up he’d have a big thick leather belt, and that's all he wore in the bakehouse.

Did he ever hit you with the belt?

R – No.

No. What did your mother wear for housework?

R – Well, she’d wear a dress but she always had what they called a pinny on in them days.

If she went out, would she ever go out with the pinny on?

R - No, she’d always take her pinny off.

Always?

R - Always.

And did your mother over wear a shawl?

R – Never, I've never seen her in a shawl. I remember me grandmother having a shawl.

Yes. So did your mother ever wear a hat?

R – Yes.

Did the always wear a hat when she went out or would she go out bare-headed any time?

R- No.

Always wore a hat.

R - Always wore a hat.

What kind of hat was it?

R- Well, sommat with a wide brim. Well, they'd be like a velour hat. You know, with a bit, up at the front and a bit of a feather in it.

And your father’d never mend the family’s shoes?

R - No.

No. How many outfits did you have at one time?

R - I had a suit which were blue, pin striped, short pants, and then I just had me flannels and doings for school. I used to have a blue shirt to go with me suit, but I only wore that on special occasions.

(650)

Tie?

R - Pretty seldom I had a tie on, unless relations were coming at Sunday and I had to get dressed up.

The blue shirt you had; were it collar attached or loose collar?

R - Collar attached.

Aye. Did you ever have a shirt when you were a lad, with a loose collar?

R- Yes, with a button so far and a back stud and a front stud.

That's it, yes.

R - And me father used to wear these here collars that went to the laundry. Hard, stiff uns. And same as he didn't feel right up to it, he’d just keep his union shirt on that he’d had on in the bakehouse and put one of these white collars on with the back stud and the front stud.

That's it. They weren't wing collars were they?

R- They were collars, they were rounded at the edges.

That’s it, yes. How often did you have clean clothes?

R - Every week, which were after bath night, Friday night.

That’s it. Have you over heard of anybody ever being sewn in for the winter? Have you ever come across that?

R - What's that, sewn in?

Yes. Their clothes sewn up before the winter so that they didn't catch cold.

R – No.

They never used to change ’em, no. Did your mother belong to any sort of a savings club for clothing and boots and shoes. Anything like that?

R - No.

No. Can you remember any change, noticing any change in the way people dressed as you were growing up? Was there … whilst you were growing up you know, in between first going to school and starting work, did any changes in dress strike you at all?

R - Long pants.

In what way?

R- Well, when you got going on to fifteen you felt a bit of a fool with your short pants, so your mother started saving up to buy you a pair of long pants to go, you know…

That’s it. And how about changes in dress in other people? You know, say in the women, or anything like that, did you notice any changes happening you know, such as skirts getting shorter?

R- Well ... but I noticed that when I were going about seventeen with the lasses that they were getting their skirts shorter and so forth.

When you were very young, the first thing that you can… when you can first start remembering these things, would it he fairly common to see people in long skirts. You know, the older women .. In long skirts.

R- Older women? Like me grandmother always had a long skirt.

Yes. And by a long skirt, you mean a long skirt down to the floor?

R- Almost down to the floor aye, and then she'd have a pinny on top of that.

Yes. And would it be fairly common to see women of that age on the streets in Earby then in long skirts?

R- Not a lot of them Stanley.

Not a lot. How about shawls?

R – No, you'd only get them that were, I should say going up seventy, seventy-five to eighty, wearing the shawl. And they did, even if they sat outside their house. They'd have their shawl over their shoulders or over their head. And instead of bringing a chair out they’d bring a buffet out.

When you were having your meals at home, did everybody sit down together?

R- Sat down together. Always.

And you'd all eat the same [food].

R- And we’d all eat the same.

Yes. And did you always have a tablecloth?

R – Yes, always. No such thing as linoleum on it, you had a tablecloth.

Yes. It was always a proper tablecloth.

R - And they'd bits of crocheting on which me mother’d done.

Did your parents, you know, were they at all strict about you at the table. The way you ate your meals?

(35 Min)

R - Oh I hadn't to talk and I never drunk until I finished eating me food.

That's the sort of thing, yes.

R - I had never to talk at the table.

And how about eating with your mouth shut? You know, how about eating with your mouth open, did nobody ever pull you up for anything like that?

R- No.

Would you say that your parents were strict with you, say about times for coming in or.. you know? If you were swearing or being cheeky or owt like that?

R - One thing, cheek, I never had to give any cheek.

What happened it you did?

R - Well me father wouldn't hit me but me mother would.

Aye. What with?

R - Feather brush mainly.

Clip round the ear happen if it were bad?

R – Well, she’d give me sharp [tap], yes.

Aye. Did the family ...

R - Like same with that, when you're talking about… I knew how far to go with the look on me father’s face. I knew how far I’d gone, and that were time to finish..

That's it. Can you remember anybody ever saying grace before meals at home?

(750)

R - No. And nobody went [to church] I never went to Sunday School, and I can never remember me mother going in .. Oh, I’m saying that, well me mother sometimes used to go to the Spiritualists. She liked to go to that.

Spiritualists?

R – Spiritualists. And she used to come home and say “Well, so and so’s told me this.” “Don't bother me with that" me father used to say.

If you had a birthday was it different from any other day?

R- No, I had no cake, birthday cake, or owt like that, but…

How about presents?

R- But presents, I'd always presents, even from relations.

Aye, visitors?

R- No.

And how about Christmas, how did you spend Christmas?

R - Well Christmas were always...Christmas dinner was always spent at home, when me half sister came and the other relations. And then the following day we can go to either me sister’s or some of the other relation. Me sister’d be at Cottontree and then me aunts were at Nelson, two of them.

So your sister at Cottontree would be living with one of your aunties.

R - No me sister at Cottontree'd be married then.

What year were she married?

R - She were married when she were seventeen.

SCG/14 October 2002

5217 words.

LANCASHIRE TEXTILE PROJECT

TAPE 78/AA/2

THIS TAPE HAS BEEN RECORDED ON JULY 17TH 1978 IN THE ENGINE HOUSE AT BANCROFT. THE INFORMANT IS JIM POLLARD, WEAVING MANAGER AND THE INTERVIEWER IS STANLEY GRAHAM.

Now, it is still 1924

R - Twenty four.

You are eight years old, and you are still living in Red Lion Street. Now then, what school did you go to?

R - I started off at three year old and I went to Riley street day school.

Three year old? Was that fairly common then?

R - Yes.

It's very early for going to school isn't it? Were there any particular reason for that do you think?

R - I don’t know Stanley. Unless it were to help a lot of women that put children out [To childminders] you see? It did save them money and that you’d expect didn't it? Because there were so many who used to be out at six o’clock taking their children out to be looked after. Well, when you got to three and there was such as the Riley Street School to go to, you went.

What age were you there ‘til?

R - Five, and then I went to Alder Hill School.

(50)

And you'd be at Alder Hill until…

R - I were fourteen.

What was the school like?

R – Oh the school were .. how can I put it? School were school, no cheek, you did as you got told. I mean to say, the same thing happens today, if you didn't want to learn you’d not learn. You got them who didn't want to learn but there were no fooling about with it, It just didn’t sink in.

How about corporal punishment?

R- Well, you got punished with a cane, a small cane with a handle on the end. And when we got to Alder Hill School we used to be taken into the woodwork room, put over the bench and walloped. I can only remember being walloped twice, and that were more for breaking windows, school windows, which I had been told about before. With either footballs or a hard ball in the schoolyard, which you knew you hadn’t to use. You could use a soft ball, but you got a bit, you know, [Careless and] took a cork ball.

Aye a corky. [A corky was the slang name for a cheap cricket ball made out of composition.] How old were your parents when they went to school? Any idea?

(100)

R- I haven’t a clue Stanley.

No. Do you know anything about their education? Have you ever heard anything?

R- I think me father were taught at what they call Christ Church School which is still going, it's on Laneshawe Bridge Road Colne.

What do you think you gained from school? You know, what benefits did you get?

R- Well, it kept you fairly well mannered did school in the old days Stanley. I know at one time we used to, before you met a teacher, we’d touch us little cap. And what can I say about teachers…well, they were there to teach and they did that job. But once you had gone out of line they soon put you back in line by being walloped, which did you no harm, and I thought it did you good.

Well, you've got a child at school now, what do you think, what would you say yourself about the difference between school then and school now? What’s the main difference?

(150)

R- Well… same as, I can’t talk about school now Stanley because I could have gone to Grammar School but I'd no interest in the Grammar School. My main interest was football and cricket. Well me daughter now, she’s not interested in school subjects. Well, I don’t think she is cheeky at school, I’ve had no reports about it but she just doesn’t give her mind to things. It’s there, the teachers admit it’s there but they can’t get it out of her.

What is she interested in then?

R - She in interested in such as hairdressing and .. she is at that stage Stanley, can’t [make up her mind] but her main interest is hairdressing. But like a lot of them now, they hear of them that’s getting these jobs such as on sewing or other duties which is making them maybe £35 a week. And she can’t see why she should continue and go to Nelson and Colne College. And the position we’re in, we would get a grant of happen £42 a year for her. Now then, she thinks she would be better off going into industry and earning such money as £35 on a sewing machine. And all her school reports for the time, as you know, wife as she is, she has had a lot of time off school but she’s not numb. If she’d give her mind to it she could do it.

(200)

[This was a delicate subject because Jim’s wife had terminal cancer and his daughter had spent a lot of time off school doing the housework and looking after her mother.]

Would you say she is brighter than you were?

R- Oh, she is a lot brighter than me Stanley.

And yet you passed for the Grammar..

R- I’ve passed for the Grammar School.

What age were that at?

R- Thirteen.

You were thirteen then? And how come you didn't go?

R- I weren't interested Stanley. My main interest was sport, it’s all I lived for were cricket and football.

Aye, and your parents never pushed you to do it?

R - Me parents never pushed me.

How about work, you know, while you were at school. Did work ever cross your mind, what you were going to do when you left school? You know, did you have any thoughts about it while you were actually at school?

R-Well, funny enough, the only thing that I wanted to do when I came out of school were go into t‘mill.

Was there anything else?

R – No, I'd gone into mills since I were twelve year old.

When you say you’d gone into mills, what do you mean?

R – I’ve gone in with somebody that's been working in a mill and mucked about with 'em you know? What they were doing and ... I don't know, I had a fascination for the mill.

Aye. So really, you had choice between the bakehouse and the mill when you left school.

R- Well, bakehouse, me dad knew for a start that didn't interest me one bit, Stanley. So he never expected me to go in the bakehouse with him.

But I mean, the thing that I mean is that it was there for you to have …

R - It was there for me if I wanted it.

(250)

How many other people do you think had a choice?

R- Not many. Not many Stanley. Because the main thing round this area were mills, which is textiles, textile industry. That were the main employment for people in them days.

So you’d leave school at what, 1930?

R- I left in 1930.

And … we’ll come on to that in a minute. While you were at school, can you ever remember the doctor coming round, you know, to examine you?

R - I can’t remember a doctor Stanley, but I remember the nurse coming. And going through your hair.

Aye. Nit nurse? [Nits are the common term for head lice which were very common].

R- Nit nurse?

That's it.

R- But as for doctors, no.

Dentist?

R- No.

Inspector?

R – No I can't remember it. Only other man I can remember coming to our school when I were there was a physical training Instructor from Skipton Grammar School, a fellow called Taylor.

Aye, and why did he come?

R- To see how we were going on with physical education. The fellow there that we had, he were actually a rugby player, a fellow called Hindley, he used to play rugby with Skipton. And .. as far as physical education went, he hadn’t much idea if you know what I mean. We just had a vaulting horse and a spring board and so it were a matter of getting on the board and going over it. This Taylor kind of knocked us into shape a bit by doing more things on this vaulting horse and more exercises. Admittedly, we didn't quite like the idea. We used to play around more often than not you know.

(10 Min)

(300)

You'd rather he laiking cricket than jumping over the vaulting horse. Aye, I can imagine it. And did you do any more study after you left school? You know, night school, anything like that?

R- I didn't do a bit Stanley.

No, nothing at all.

R- Nothing at all.

So you left school.

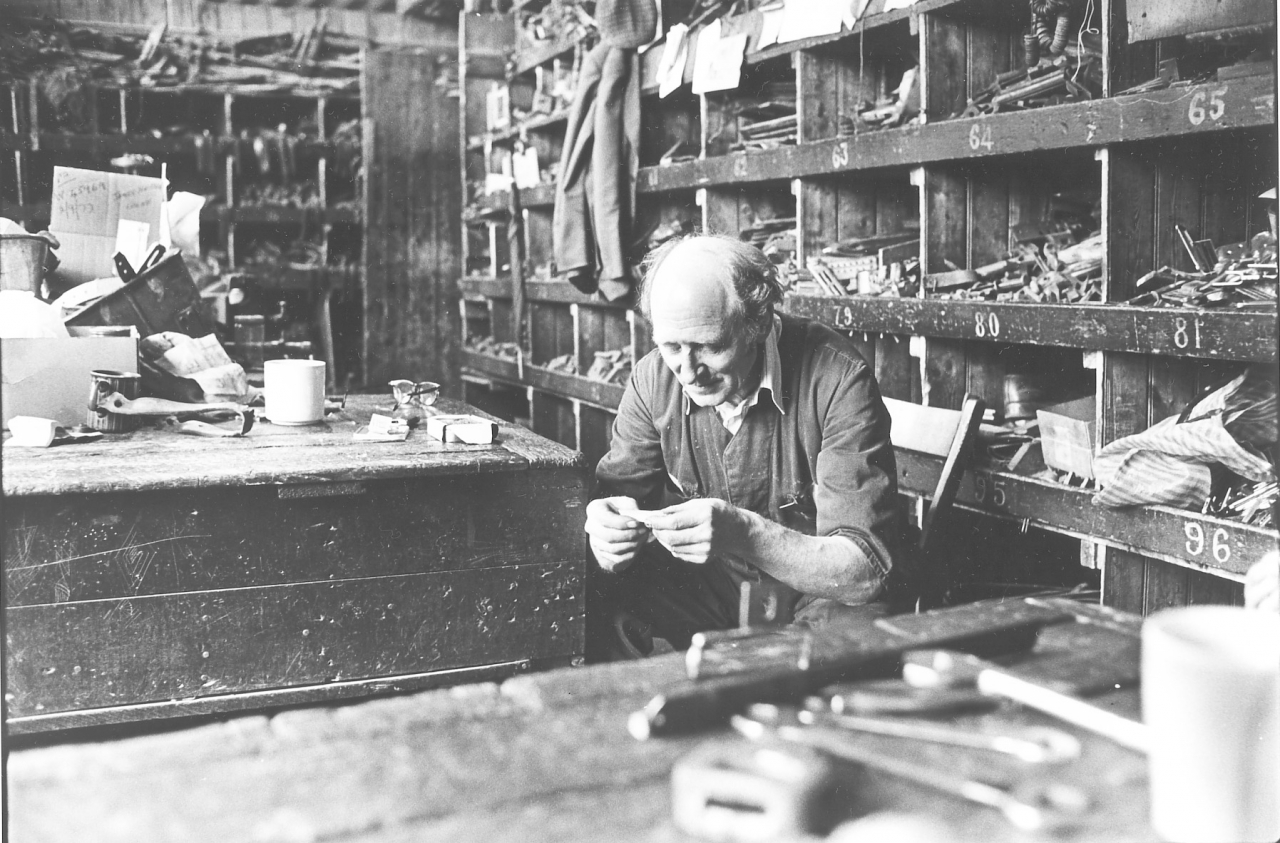

R - When I left school what I did …even getting into mills in them days, it were hard Stanley. You couldn’t just walk into a mill and get a job. There were such things as tenting, where you'd go in at twelve or thirteen and, and go with weavers and you'd be a tenter, you’d happen get half a crown, such as that; and then it were difficult to get in, they were only on four and five loom in them days.

If you went in as a tenter, that’d be with somebody who were probably on five looms or a good weaver wouldn’t it?

R- Five looms, a good weaver.

Who paid the tenter?

R- He paid them, he paid it.

The weaver?

R- The weaver in the old days. And by…But you had to work for your money!

Now then, over a period he’d been with you, he’ll get paid by the firm for tenting if you were showing any signs…

R- But you’d got to he showing signs before they'd start to pay.

So it would nearly have to be a relation or a friend of the family that you were tenting for?

(350)

R – Yes, that’s right, somebody that worked there, somebody you knew, a relation or a good friend of the family.

How about going in before you were actually old enough to go to work, and learning a bit so that you were a better man when you went. I wonder if some of that went on?

R- Well, this is what I did when I went from school at four o’clock. I used to go into a mill and do a bit of bundling, cloth-look bundling and tying ‘em up. I hadn’t the strength you know? But they used to have a presser in them days and it used to come down and then press them tighter and it were far easier to tie the strings up with that. And then I'd go up into the twisting room, preparation room and they’d have a regular reacher-in who put the ends on a hook which were pulled through the healds. Well, if he wanted a break it was just my job to have a sit down and I were only too keen to have a bit of a do at this. And yet, when I left school, I couldn’t get into the mill and I had to go in the bakehouse with me dad.

So you left school when you were fourteen?

R - But when I finished in the bakehouse, which was around two or three o’clock, what did I do then? I used to go into the mill after that period to spend a bit more time in the mill.

Anywhere in particular?

R - I used to go to Sough Bridge, which were more of a man-made fibre place than cotton.

In them days? Oh, what would that be, Viscose?

R- Viscose.,

Aye.

R - Made of Celanese and such as that.

Aye that’s it. Jimmy Nelson’s were on it weren’t they? What do you call that stuff? Made out of wood shavings?

R- Lustrafil. I’d do it [The bakehouse] but I knew it weren’t going to do me any good, I weren't interested at t’bottom. I’d set me mind on sport, or going into the mill.

(400)

So you left school at fourteen, and half timing would be finishing then would it?

R- Half timing? There weren’t much of it then Stanley in 1930. We used to get in and you'd start off as a proper learner you know.

Yes. Would there be any half-timing going on at all that you know of for sure then?

R- I can't say there were in 1930 Stanley.

Yes. So when you left school you couldn’t get a job in the mill?

R- No.

So, of course, 1930, it’d be a bit dodgy wouldn’t it? Just coming into the bad times? Yes.

R - Yes, bad times.

Yes. Well you were into it weren’t you, 1928 it started, yes.

R - Twenty-eight … started.

So you tried for a job though? Tried all over?

R – Yes. Tried all over.

So you worked in the bakehouse with your dad? And then, in your spare time, you were into the mill whenever you could be?

(15 Min)

R- I were into the mill. Like same as with that, I had a pal, one or two pals, in the mill. So I went in to them. And then I'd get knowing somebody else in t’mill and I’d go and do a bit for him and …

Well, knowing you, Summer’s afternoon and three o’clock …

R – No, wait, but you see on that, what I did, I went on to the cricket field in summer and go on two afternoons, from half past two ‘til roughly round about half past four.

Which cricket field were that?

R- That’d be at Earby.

Were that nets?

R – Nets. And there’d always be t’pro’ about. And that were a good thing for me, because it got me two afternoons in on the cricket field with the pro’ bowling.

Aye. What were the attitude to you going down? Were they like glad to see anybody that’d come down? That were showing a bit of promise, you know, showing signs?

R - Cricket players? Oh yes, they were dead keen at Earby on cricket Stanley. If you talked to anybody about cricket they always said “Oh, Earby? Oh, cricket mad.” I mean to say, even going back to The 1930’s.

Jim as a young cricketer in Earby.

(450)

Yes.

R – And, such as that, it were…what? Same as if one player’d leave Earby and come Barlick to play. Gosh! It were like defeat. If Barlick’d play, they were in a different league bear in mind. Now if Barlick went and played Earby and this lad were with them. In a friendly even, oh it were hell on earth for the lad, he’d get booed as soon as he were coming out to bat. Oh aye. But you see, what went on a lot in them days with Earby, there were those lads that went to t'Grammar School. Now they couldn’t get out of the idea, they always thought that the Grammar School lads were better than what we could call the local lads were. You see you could, you’d start off in that team. Now as soon as it come, their Summer period, their break, irrespective if you’d done fairly well, you’d be out of that team and these Grammar School lads would take precedence over you. And their performances could go on for weeks doing nothing but they’d still be in. Now this is what got everybody, this bit of feeling you see

Aye, gentlemen versus players Jim. Aye, that’s what it is.

R – Yes. So me father had different ideas and he said “As soon as you can move, you move!”.

Aye, ‘cause you actually started off at Thornton didn’t you? Yes, that was because they didn't think you were big enough at Earby.

R - At Earby, that’s correct.

Aye, still…

R - but you see, on these does Stanley, as I'm saying, when you were at school. There were even such as a woodwork room at Alder Hill ..quite a good school were Alder Hill. And there were a cookery room for the girls, even in them days, a beautiful cookhouse and that for them and the woodwork room were beautiful. Except when you went in to be laid over the bench and walloped! I can just remember one teacher, Thornton, Bobby Thornton, now I would say he was the worst teacher there were at that school.

In what way?

R - He didn’t give two hoots whether the lads were learning or whether they weren’t and he always used to suffer anyone who moved out of his class into the next class. You were way behind if you see what I mean. He were all right, he were sending a lad down to the paper shop and getting his Sporting Pink for the horse racing. And he would sit with his Sporting Pink on his desk, sorting winners out. Well, everyone took a bit of advantage of this and started throwing inkpot blobs up and down. But you knew, after you’d moved out of his class, that were it, work started then.

What standard were he teaching?

R- What would it be? Class III in them days.

No. Like that were a fairly important standard weren’t it. Aye.

R - You see, he looked after the garden, we used to have a bit of garden up at Alder Hill and all. And you used to have one afternoon gardening. I never knew what they did wit' vegetables that they grew, wherever they went but .. they used to grow a lot of vegetables and it were quite interesting with him. Now give him his due he were a good gardener, but as far as the three R’s were concerned, he were bloody hopeless.

How about school meals, were there any school meals then?

R - No school meals. No free meals, no nothing Stanley.

No school meals.

R - And one thing about school Stanley, you didn’t walk out of school as though you were walking out of a cinema or owt like that, wandering about, you had to march out. And your teacher’d be stood there and if you didn’t march you used to get one wallop and it’d be either on your bottom or your leg. But it were fairly orderly

(550)

And there wore no such thing as what they talk about now, stealing that goes on at schools and that. It’s one thing you’d never… everyone used to have a peg for their cap and coat and they were still there, nothing missing.

Really then, you’d say as a whole that standards of behaviour have declined at schools then, since you were there.

R – Oh Stanley. It's when I go up to that school, it’s shocking.

[Jim had a daughter at what was then New Road School but is now called West Craven High School in 2002. This is the school he is referring to.]

Well I must tell you that that's the impression that I get but I often wonder how prejudiced we are.

R – Oh it’s pathetic, it is, you'd never see the lads throwing pennies, like we call those two pence pieces don’t we. A gang maybe thirty, throwing these up against the school wall and the winner takes the lot. That's unheard of. But yet they dare do it up there, I’ve seen ‘em doing it at dinner time. And the way they wander in and wander out, no such thing, you marched in orderly and you came out orderly.

Aye. And you didn’t come out till four o'clock either. It's a thing that strikes me many a time, Christ Almighty they’re coming out of theer at three o’clock.

R - And if you even want to go to the toilet your hand had to go up “Please Sir” or “Please Miss”.

Well, don’t they know?

R- I don’t know as far as I can see they just say “Reight, I'm going to the toilet", and that’s it.

Aye, I’ll have to ask our Margaret about that. I don't know about that.

[My eldest daughter went to the same school.]

R - No, it's so different Stanley, This is why, I don’t know whether we are the old fashioned type or what, but to me it seems more orderly and better mannered in those days weren’t they? Don’t you think so?

Well, as I say, that’s the impression I get.

(600)

R - I’ll give you another instance Stanley. I’m not saying anything about people with beards Stanley or anything like that, but in the old days you’d never see a teacher going to school without a collar and tie. You’d never see anybody wearing a rolled up shirt [sleeves] or a damn pullover that looks as though it had been slept in. Everybody would be, the teachers would be tidy and smart.

In other words they were setting an example.

R- They’d set an example. Same as with that, you even went to school in clogs but them clogs’d be polished.

Did you go to school in clogs?

R - I went to school in clogs, I could kick stones about better in the school yard with clogs than I could with shoes.

Aye, I think we are beginning to sound like a couple of reactionaries.

R-No. I believe in school Stanley, but the way they carry on, I think it’s disgusting. I can honestly say that when you went to the toilets at school they were clean. And they were kept clean. But now… And as for a broken window Stanley, you’d pay for that, and you had to pay. But not now.

(25 Min)

Oh they'll set fire to a shop now, never mind break a window. And in those days ...and this is something that has a bit of bearing on it really, In those days there were things like parent teacher associations were there?

R- No.

To your knowledge did your parents ever go to the school to discuss with the teachers how you were going on or anything like that?

R- Never Stanley. I can only remember me father, well, me father would never have gone to school even if they'd half killed me. But me mother went once.

Aye. What did she go for?

R – Well, once I were walking out, and as far as I know I were going out well behaved, and a fellow called Seed which were the Headmaster, he used to carry a walking stick, and it were one of these curly uns, and he just caught me such a crack behind me leg it blistered my leg from above my knee right down to me muscle and me calf. And me pants, me short pants kept rubbing on this and then me mother says "What are you scratching?” you see.

(650)